TV

TV « In Which It Was Nothing New For David Simon »

Wednesday, September 29, 2010 at 10:35AM

Wednesday, September 29, 2010 at 10:35AM

First Folklore

by HELEN SCHUMACHER

In 1993, the year that Homicide: Life on the Street debuted on NBC , the number of murders in Baltimore hit an all-time high of 379 deaths. (Coming out of the crack epidemic of the ‘80s, the murder rate for that year was 48.1; New York City’s was nearly half that at 25.9 deaths per 100,000 people.) The series was based on the book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, written by a journalist named David Simon, who had five years earlier — at the age of 28 — spent a year following Baltimore’s premiere men in blue as they investigated the city’s most violent crimes. Since the publishing of the book and the series’ seven-season run, Simon has earned the reputation as being one of the nation’s most talented crime-folklorist for his work on The Wire. With the critically acclaimed show, the portrayal of Baltimore that Simon had been building for years became an urban legend.

A circa 1989 David Simon with real-life detectives Sgt. Terrence McLarney, Det. Robert McAllister, and Det. Robert Bowman.In his book (and in the series), Simon’s focus was not on the crime figures of Baltimore, but on the occupational culture of its police force — not an easy topic to parse. The psyche of his detectives reflected the complexity of their role in the community. Constant exposure to the depravity of humankind isolated them from family, from lovers, and from the communities they’d sworn to protect. No matter the color or income of the neighborhoods the detectives found themselves in, they were nearly always confronted with civilian antagonism stemming from deep-rooted notions of police corruption, racism, and paranoia.

A circa 1989 David Simon with real-life detectives Sgt. Terrence McLarney, Det. Robert McAllister, and Det. Robert Bowman.In his book (and in the series), Simon’s focus was not on the crime figures of Baltimore, but on the occupational culture of its police force — not an easy topic to parse. The psyche of his detectives reflected the complexity of their role in the community. Constant exposure to the depravity of humankind isolated them from family, from lovers, and from the communities they’d sworn to protect. No matter the color or income of the neighborhoods the detectives found themselves in, they were nearly always confronted with civilian antagonism stemming from deep-rooted notions of police corruption, racism, and paranoia.

Their relationship to their job was further complicated by a lack of support from the brass upstairs, knowing that the only thing the captain wanted to hear was that the clearance rate was going to please the politicians and that the latest red-ball case was staying out of the news. Even their relationships with each other were dysfunctional.

At the center of the Homicide was Lieutenant Al Giardello’s squad. The shift lieutenant was played by Yaphet Kotto. His magisterial onscreen presence was perhaps due to his royal lineage (he claims Queen Victoria as an ancestor). The Sicilian he played was always the tough but fair leader.

Melissa Leo played Detective Kay Howard. The daughter of a Chesapeake Bay fisherman and a thorough and observant detective, Howard passed the sergeant’s exam halfway through the series.

First appearing as a lieutenant, then as a captain, then finally demoted to detective is Megan Russert talking to Ned Beatty’s seasoned Det. Stanley Bolander.

Detective Mike Kellerman joined the squad from the arson department. He would become disgraced first through allegations of taking bribes and later the shooting of drug kingpin Luther Mahoney. Here we catch the detective in a pensive moment.

The baby-faced Det. Bayliss was haunted throughout the series by his first case as primary detective — the murder of Adena Watson. The young girl was mostly likely killed by an arabber she had befriended, however Bayliss was never able to get a confession out of the man and put the red ball down.

Perhaps the most memorable character of the show was squad diva Det. Frank Pembleton (Andre Braugher). He was the undisputed master of the Box. If you were lucky enough to catch him at work from behind the small brick room’s one-way mirror, you’d witness something closer to an opera than the questioning of a suspect.

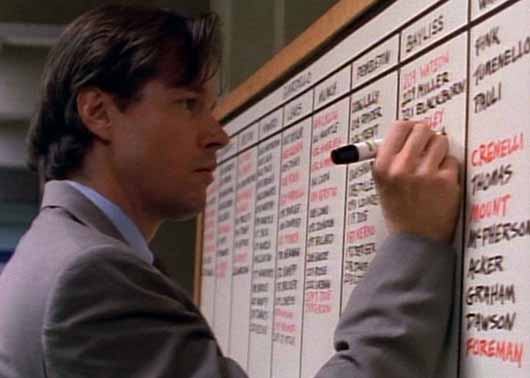

Homicide was an attempt to not only show the detective’s mind state, but also the slang, the rituals, and the tools of the occupation. One professional tool that became an integral part of the show was the bureaucratic relic of the criminal justice system known as the Board. It served as a stubborn reminder of the current year’s death tally. The Board was a white board that has been divided into columns — one for each detective—and under each of the detectives’ names, a list of victims, either in red or black depending on the case’s open-or-closed status. As the year moved on the list got longer. It was where the life of a murder detective and the life of a victim intersected.

Simon described the Board allegorically: "In the time that it takes the coffeepot to fill, shift commander Lieutenant Gary D’Addario (Al Giardello in the series) can approach the Board as a pagan priest might approach the temple of the sun god, scan the hieroglyphic scrawl of red and black below his name, and determine who among his [detectives] has kept his commandments and who has gone astray. The board reveals all: Upon its acetate is writ the story of past and present. Who has grown fat on domestic murders witnessed by half a dozen family members; who has starved on a drug assassination in a vacant rowhouse. Who has reaped the bountiful harvest of a murder-suicide complete with a posthumous note of confession; who has tasted the bitter fruit of an unidentified victim, bound and gagged in the trunk of an airport rental car."

Like any good scholar of folklore, Simon knows the vernacular of his subculture. The two terms used throughout the book to describe a case are dunker and whodunit. The case of the murder-suicide complete with a posthumous note of confession is a dunker. The unidentified victim in the trunk of an airport rental car is a whodunit. The detectives of the network TV series were of course able to solve both — either by luck, following the evidence, or a psychological beat-down in the Box.

The Box refers to the interrogation room and setting of the show’s most dramatic moments. Inside the Box a carefully acted seduction takes place, with the detective exploiting the criminal’s stupidity and fear for a confession. “The effect of the illusion is profound, distorting as it does the natural hostility between hunter and hunted, transforming it until it resembles a relationship more symbiotic than adversarial. That is the lie, and when the roles are perfectly performed, deceit surpasses itself becoming manipulation on a grand scale and ultimately an act of betrayal,” writes Simon.

What a suspect could expect to be confronted by once inside the Box. From l to r: detectives Meldrick Lewis, John Munch, and Tim Bayliss.Simon wasn’t Baltimore’s only proponent to take part in the series. The patron saint of Charm City’s freaks and deviants, John Waters appeared as a prisoner being escorted by Chris Noth in one of several Law and Order crossover episodes. Barry Levinson was the show’s executive producer. In his "Baltimore films,” Levinson wrote and directed four fables of growing up in the city in the ‘50s. As he did with his semi-autobiographical films, Levinson weaves himself into the series in a self-referential episode where a suspect is chased into an alley where the director just happens to be shooting a show called Homicide.

What a suspect could expect to be confronted by once inside the Box. From l to r: detectives Meldrick Lewis, John Munch, and Tim Bayliss.Simon wasn’t Baltimore’s only proponent to take part in the series. The patron saint of Charm City’s freaks and deviants, John Waters appeared as a prisoner being escorted by Chris Noth in one of several Law and Order crossover episodes. Barry Levinson was the show’s executive producer. In his "Baltimore films,” Levinson wrote and directed four fables of growing up in the city in the ‘50s. As he did with his semi-autobiographical films, Levinson weaves himself into the series in a self-referential episode where a suspect is chased into an alley where the director just happens to be shooting a show called Homicide.

Levinson with squad videographer J.H. Brodie and Det. Lewis. Homicide was primarily filmed in the historic Fell’s Point neighborhood of Baltimore.Not all of the show’s action took place on the job. We also got to learn more about the detectives through their barroom philosophizing. The storytelling tradition of law enforcement officers has long found sanctuary in the cop bar.

Levinson with squad videographer J.H. Brodie and Det. Lewis. Homicide was primarily filmed in the historic Fell’s Point neighborhood of Baltimore.Not all of the show’s action took place on the job. We also got to learn more about the detectives through their barroom philosophizing. The storytelling tradition of law enforcement officers has long found sanctuary in the cop bar.

Stories bearing the trademark gallows humor of the profession are passed down from veteran to rookie. There is the one about the polygraph-by-copier (now a staple of cop lore), where a confession is obtained after a suspect has been tricked into believing a Xerox machine pre-loaded with paper bearing the statements Truth and Lie is tracking the veracity of his answers.

There is the one about the black widow Geraldine Parrish (Calpurnia Church), a part-time voodoo priestess who collected life insurance on five husbands before finally getting caught after the ploy to collect on her niece’s life is botched. There is the one about the petty thief with the unfortunate nickname of Snot Boogie.

Baby Gyllenhaal and Robin Williams, Steve Buscemi in the Box, John WatersBy calling Simon a folklorist, I don’t mean to detract from the authenticity of his work. After all, the reporter’s attention to facts that goes into his writing is a major reason he has been so successful. My point is that Simon’s work concerns itself with the ways in which people make meaning in their lives. As the scholar Mary Hufford has said, "folklife is lodged in the various ways we have of discovering and expressing who we are and how we fit into the world.” Homicide looked at the role of Baltimore’s murder detectives in the national ethos.

Baby Gyllenhaal and Robin Williams, Steve Buscemi in the Box, John WatersBy calling Simon a folklorist, I don’t mean to detract from the authenticity of his work. After all, the reporter’s attention to facts that goes into his writing is a major reason he has been so successful. My point is that Simon’s work concerns itself with the ways in which people make meaning in their lives. As the scholar Mary Hufford has said, "folklife is lodged in the various ways we have of discovering and expressing who we are and how we fit into the world.” Homicide looked at the role of Baltimore’s murder detectives in the national ethos.

Benjamin Botkin, considered a father of the study of folklore, was one of the first academics to recognize oral history as a legitimate historical source. In 1954 he wrote a book called The Sidewalks of America: Folklore, Legends, Sagas, Traditions, Customs, Songs, Stories, and Sayings of City Folk. Simon’s A Year on the Killing Streets is in effect a modern regional translation of the work. Like Botkin, Simon understood the importance of an authentic conversation with the subjects of his work and the honest relaying of their stories.

The best known piece of lore to come out of the city was written by lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key while locked aboard the HMS Tonnant during the Battle of Baltimore. The now-sacred text, with its imagery of the broad stripes and bright stars and the rockets’ red glare, is grandiose and inspirational, but its pomposity doesn’t resonate with everyone. For others, the truth and spit is in the tales swapped at 3 a.m. at the desolate end of Clinton Street over cheap beer and whiskey — it is in the blue-blooded story of Bodymore, Murderland.

Helen Schumacher is a contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Brooklyn. This is her first appearance in these pages. She tumbls here and here.

"A Bit of Glue" - The Tellers (mp3)

"Hugo" - The Tellers (mp3)

"Second Category" - The Tellers (mp3)

david simon,

david simon,  helen schumacher,

helen schumacher,  homicide,

homicide,  the wire

the wire

Reader Comments (2)

Nice piece. But, just FYI, all Baltimore bars close at 2 am. :)

Thanks for this, i love this show