FILM

FILM « In Which Pedro Almodóvar Is Both Violator And Violated »

Monday, November 14, 2011 at 11:35AM

Monday, November 14, 2011 at 11:35AM

Manipulation Without Intervention

by KARINA WOLF

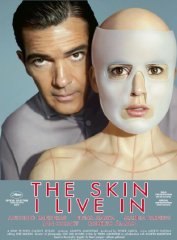

The Skin I Live In

dir. Pedro Almodóvar

117 minutes

The first five minutes of a movie are like the opening parries of any relationship — the early frames are petitions to invest in the story; looking back, the smallest gesture becomes an index for its unspooling. During the credits of The Skin I Live In, the director Pedro Almodóvar trains his camera on a book splayed across a workshop table: a collection of the works of Louise Bourgeois.

The first five minutes of a movie are like the opening parries of any relationship — the early frames are petitions to invest in the story; looking back, the smallest gesture becomes an index for its unspooling. During the credits of The Skin I Live In, the director Pedro Almodóvar trains his camera on a book splayed across a workshop table: a collection of the works of Louise Bourgeois.

Almodóvar often uses the texts of other artists as a touchstone for his narratives: Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire becomes a way to explore reinvention in All About My Mother, the steps of Pina Bausch’s “Café Müller” are a means to examine the attenuation of grief in Talk To Her. The appearance of Bourgeois’ work announces Almodóvar’s direction for The Skin I Live In: among Bourgeois’ most stunning achievements were the figures which she tailored from scraps of clothing — gently stitched-together bodies that accordion from one another like paper dolls; torsos linked by copulation or, between mother and child, by placenta. They suggest the inextricable ties of biological intermingling, of libido and maternity.

Bourgeois was a confessional artist and used materials and techniques – sewing and needlework, for example — related to her origins (her parents owned a tapestry gallery) to explore questions of identity and self-definition. Perhaps most disturbing are her series of patchwork heads, which resemble balaclavas, lucha libre masks, or more gruesomely, the skins collected by Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs. These heads suggest the disfigurement that is a component of transformation and of survival.

In The Skin I Live In, a loose adaptation of Thierry Jonquet's novel Mygale (Tarantula), an artisan fashions similar cloth heads. The creator is Vera (Elena Anaya), a stunning woman with moist, sad eyes, who spends much of the film kitted out in a flesh colored unitard. Vera is patient, prisoner and cherished fetish object in the home-laboratory of Dr. Roberto Ledgard (Antonio Banderas), a geneticist.

As the doctor and his housekeeper Marilia (Marisa Paredes) surveil the young woman in a locked room — retrieving food from a dumbwaiter, taking medications, practicing yoga, reclining with an Odalisque's awareness she is being watched — one wonders how Vera came to be a privileged captive. She has an unsettling devotion to her jailor, and the investment seems reciprocal. Ledgard is as fixated upon his patient as she is by him, perhaps because Vera is the benefactor of an illicit form of Ledgard’s work. He has developed a skin that is impervious to fire. The suit Vera wears is to protect her man-made cells as they graft to her body.

Marilia explains that the doctor's wife killed herself after being charred in a fire, but for much of the film, Almodóvar and cast generate a hope that Vera might be the doctor’s wife — resurrected by the resources of a fervent husband. Certainly, Zeca, the crazed son to Marilia and unknown half-brother to Dr. Ledgard, is overpowered by the notion that Vera is Mrs. Ledgard. After a tussle with Marilia, he gains entry to Vera’s chambers, sheds the carnivale costume that disguises him, and perpetrates a bloody rape.

There are many kinds of violation in The Skin I Live In. Almodóvar is intent on unsettling the audience — keeping the loyalties and orientation slightly askew. As Marilia watches the rape through the monitors, she mysteriously urges Ledgard to "kill Zeca, kill them both." Ledgard shoots the attacker and rushes to comfort his violated patient. The structure of the household — and the film — is forever altered: in deference to her recent violation, Ledgard sets Vera free, and the two begin a chaste romantic relationship.

Almodóvar works through the conventions of his favorite genre — melodrama — and the story figure-eights through time to explore the emotional phantoms that shape the present action. The subplot of Ledgard's daughter, an emotionally fragile girl who is institutionalized after her mother’s death, becomes foreground: the story's main action is the trajectory of Ledgard’s revenge upon a youth who date-rapes his daughter.

With his career in American animated franchises, Antonio Banderas can be dismissed as modest talent with an exceptional face. Here, in his native language, Banderas has never been as sinister. As Ledgard, his beauty is hollowed out by loss, then dehumanized by revenge. He displays a dispassion that would fit as easily on any number of Hitchcock’s anti-heroes. But more importantly, there is the seductive power of the violator and the violation itself.

One of the great tropes of cinema is the fetishisation of female (and male) flesh — the wish fulfillment of intercourse with exceptionally beautiful people. The exquisite horror of The Skin I Live is the complicity of the viewer in the ravishing of Elena. What does it mean when you understand that (spoiler here) you’re watching a man have sex with a man who’s been given the perfect form of a flawless woman. What are you witnessing and what are you wishing for?

The Skin I Live In is a film that has a double life — the behaviors we watch at the start of the film have completely revised implications at the film’s end. And so the movie must be viewed a second time, in the theater or the theater of the mind, to evaluate your understanding of the characters, their motivations and behavior.

As with other Almodóvar films, The Skin I Live In addresses libidinous passion, unrestrained violence as an expression of self, and, most importantly, identity — that which is given, rendered, and staked out. Therapeutic capture is familiar territory for Almodóvar, who more than any filmmaker parses the paradoxes of violence. He has made several films (Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down; Live Flesh) in which an amorous man holds captive the object of his lust/affection. Almodóvar invariably finds the tender and the humane in the violator without leaving his victim subordinate.

The violations become our own transgressions in reassembling the film. Isn't it the work of great novels and films not only to allow the audience to understand the lives of others, but to render the reprehensible, and even evil, identifiable — to hold up a mirror? Almodóvar is equally excoriating when he addresses his own role as creator. Ledgard's work, like that of Dr. Frankenstein, casts a terrible shadow over the act of creation. On the other hand, the work of Vera, who stitches together rows of cloth figures and scrawls numbers and mysterious phrases on the walls of her room with an unexplained urgency, is a plea for art's resurrecting properties. As Louise Bourgeois stated: "Art is a guarantee of sanity. That is the most important thing I've said."

Karina Wolf is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in New York. She tumbls here and twitters here. She last wrote in these pages on Roman Polanski's Repulsion. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here.

"In the Present" - Miró Belle (mp3)

"Heart String Swelling" - Miró Belle (mp3)

"21 Years Old Questions" - Miró Belle (mp3)

Reader Comments (1)

http://www.amazon.com/Tarantula-Thierry-Jonquet/dp/1852428953