BOOKS

BOOKS « In Which We Imagine Ourselves As Veronica Geng »

Wednesday, November 16, 2011 at 10:25AM

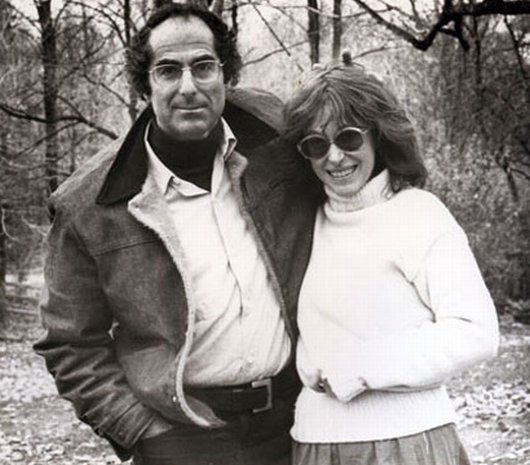

Wednesday, November 16, 2011 at 10:25AM  with Philip Roth

with Philip Roth

Veronica in the Extreme

by HELEN SCHUMACHER

Even after her death, her friends didn't hesitate to call her a monster. Veronica Geng, a contributor and fiction editor at the New Yorker during the '70s and '80s, was stubborn to a fault. Roger Angell, who was responsible for bringing Geng to the magazine, declared her the hardest person he ever had to edit. Best known as a humor writer, Geng's satire could be relentlessly brutal, but she wrote with a sui generis wit and dexterity that gave her work an extraordinary quality and had colleagues willing to look past her fierce temperament.

Geng joined the New Yorker in 1976 after a piece she wrote for the New York Review of Books, a film review written as a parody of Pauline Kael, got the attention of Angell. The short piece mocks Kael’s notoriously overenthusiastic review of Robert Altman's Nashville. In Geng's spoof the movie is called St. Pete, and Geng writes: "The picture’s a knockout. There’s nothing the matter with it. It's Altman’s farewell to the movies, with their Esperanto sensibilities, their bogus art and darling 'actors.' It's as if the whole sanctimonious-aesthete-in-tinsel-land scene bombed out ten years ago, and he’s the only one who’s noticed, or who's cared."

Veronica Geng (the surname is Alsatian) was born in Atlanta, Georgia, and spent much of her childhood in Philadelphia, where she lived with her younger brother and parents. Her father worked as an officer in the army's quartermaster corps and, in her teens, he moved the family around Europe — to Heidelberg, Munich, and then Paris. After high school graduation, Geng returned to the United States to study at the University of Pennsylvania (where she wrote her honors thesis on Seymour Glass) before moving to Manhattan and taking up with the city’s literary scene. Up until her breakthrough NYRB piece, Geng had been laboring away in book-editing gigs and composing freelance pieces for glossy women’s mags under the pseudonym Phyllis Penn.

with her brother

with her brother

In 2007 Geng's brother, Steve, a career thief and drug addict, published a memoir about his junkie exploits and relationship with his sister. In it he describes Veronica as an extremely private, guarded girl who was endlessly rolling her eyes at those less quick-witted than her and who liked to make her brother laugh with impressions of the politicians of the McCarthy hearings. She was a dedicated student and reader, but still known to smuggle gin in perfume bottles on Girl Scout trips.

While Steve's memoir provides the rare account of Veronica's childhood, traces of the personalities and events that shaped it show up everywhere in her writing, in particular, the voice of her bullying father, an insecure man who hid behind military diction (an infantry manual was among the reference books Geng kept at her desk). As fellow New Yorker Ian Frazier, with whom she shared a deep, long-standing friendship, points out in the introduction to one of her collections, of all the voices Geng used in her writing, the voice of the overbearing American guy was the one she knew best. "She could be playful with the overbearing-guy voice, and she sometimes even celebrated it," Frazier wrote. "More often, though, she fiercely mocked it. Her contempt for it, and other contemporary stupidities, was withering. … She just understood better than the rest of us how coercive, how oppressive, such voices can be."

Undoubtedly, one of her greatest virtues was her manipulation of the voice of power. While most of us grow numb to its tyranny, she never lost her ear for it, nor her indignation at its pompousness. Often she executed her slick attacks by taking the quotes of politicians and placing them in a new context, exposing their asininity and hypocrisy. Fittingly, she claimed her two favorite books were Alice in Wonderland and the paperback collection of the Watergate transcripts.

"My Dream Team" begins with an epigraph from the 1991 Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill hearings of Senator Arlen Specter questioning Hill as to why she never took exact notes on Thomas' sexual harassment, knowing that her "evidentiary position would be much stronger" if she had. In the piece, an assistant stealthily takes stream-of-consciousness notes (but with full attention to proper legal notation) while in conversation with a lecherous co-worker.

I hereby affirm that the person whose words I just wrote down while pretending to work and ignore him, and whose actions I intend to note insofar as I can see while feigning inattention and writing fast enough to keep up with his lohgh lhoggohr shit what a stupid word to pick under this kind of pressure his blabbering—I do solemnly swear and state that this person is one and the same Mr. Barry Sloat, co-worker and subject of Contemporaneous Notes Parts 1-85; and further I avow that this, Part 86, commences on October 6, 1995, 3:45PM, when Mr. Sloat made known his presence in my office doorway, whereupon I once again made Standard Warning Statement (as per Manual p.5) in conformance with EEOC Anti-Entrapment Guidelines (Attachment to Part 1) and then wrote down what he said, contemporaneously with his saying it. By the way (chance here to squeeze this in while Mr. Sloat pausing for dramatic effect enjoyed by him alone), I also attest that I am not type of woman who normally uses 'shit' as expletive, but crossing it out now might look as if I have something to hide.

Mr. Sloat resumed talking few seconds ago but only telling au pair anecdote again (#4: see Appendix A, Full Versions of Au Pair Anecdotes He Tells). Heeeeere's punch line!...

Geng cloaked sharp observations in nonsense, and sometimes nonsense was just nonsense. Her work could be as difficult as it was funny. In an article for New York magazine published upon the release of a posthumous edition of Geng's essays, Jennifer Senior wrote, "Geng was one of the writers [Wallace] Shawn hired during the sixties and seventies whose work was extravagantly intelligent but not always intelligible — 'extreme writers,' as his successor, Robert Gottlieb, so aptly called them, who would require time and faith to develop a constituency."

Initially given this time and faith, Geng thrived at the New Yorker, taking on a role as fiction editor. Frazier called her the best editor of humor pieces he had ever worked with. He has said, "I wrote humor pieces specifically for her to read, and when she didn't like them, as happened sometimes, I would be depressed for days and consider radical revisions of my entire life in order to make myself funny again." As an editor, she worked with Donald Barthelme (with whom she shared a knack for absurdist quips), Jamaica Kincaid, Roy Blount Jr., William Trevor, and Milan Kundera. Philip Roth came to depend on her as an unofficial editor for nearly all of his work.

In one of her best known shorts, "Love Trouble Is My Business", she draws inspiration from a quote by Village Voice columnist Geoff Stokes that commented on a Times article containing the line: "Subjects such as the Soviet Union seem to haunt Mr. Reagan the way vows to read Proust dog other Americans at leisure." Stokes' declaration that the Times article would be the only time the words "Mr. Reagan" and "read Proust" would appear in the same sentence inspired Geng to write a noir detective story using the words "Mr. Reagan" and "read Proust" in every sentence. It begins: "I glanced over at the dame sleeping next to me, and all of a sudden I wanted some other dame, the way you see Mr. Reagan on TV and all of a sudden get a yen to read Proust.” True enough! It later continues: “She chuckled insanely, like Mr. Reagan looped on something you wouldn’t want to drink while you read Proust. Then she touched me, with the practiced efficiency of a protocol officer steering some terribly junior diplomat through a receiving line to meet Mr. Reagan — and funny, but I got the idea she wasn’t suggesting we curl up and read Proust. As her hand slid along my thigh, I noticed that she wore a ring with a diamond the size of the brain of a guy who read Proust all the time, and if I'd been Mr. Reagan, I’d have been dumb enough to buy her another one to go with it.”

In her capable hands, what could have been a silly exercise in form was turned into a taunting and brilliant sketch. Geng commented on composing the piece, “What a gift! … Stokes’s premise was so ripe that even writing bad lines was fun — like making lists of improbable rhymes. ("It was too early to read Proust, so I went out and bought myself a pint of 'Mr. Reagan'.") … The title (which piggybacks on Chandler) has an extra meaning for me, because it's my business to love trouble."

Geng did not just love trouble, she created it. Her brother claims it was a favorite game of her and Frazier’s to slip inappropriate and senseless material past their editors. She fought bitterly with those who tried to edit her writing, yet she was heartless when she thought a friend's work wasn’t up to par. In 1992, a dispute with Tina Brown, who had recently been hired as editor of the New Yorker, led to Geng's departure from the magazine (whether she quit or was fired is up for debate). Her personal life could be similarly rocky; the scorn that was aimed at politicians and the ilk with great acuity in her writing was less charming when she directed it at her friends and lovers.

Geng never married, instead preferring to be the mistress to professional athletes, actors, musicians, and other writers. Mark Singer, another New Yorker staffer whom she dated, said, "She was one of the most feminine women I ever met. In her posture, her figure, her walk..." Her most significant relationship was with the photographer James Hamilton. It was Hamilton who would arrange her memorial service after she died from a grapefruit-sized brain tumor on Christmas Eve 1997.

It may have been characteristic of Geng's writing to adopt the voices of others, but she did it with flair and humor distinctly her own. From those voices, she crafted work the reader could crawl into — her essays smug shelter from bland hegemony. Her brother recalls a conversation with Roger Angell after her death when Angell told him: "When people as different as Veronica come along, everything changes. Veronica changed humor because there was nobody like her. Your sister was so passionate about the work she did here she changed all of us."

Helen Schumacher is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Brooklyn. She tumbls here and here. She twitters here. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She last wrote in these pages about the films of Clouzot.

with her brother Steve

with her brother Steve

"You and the New World" - Treefight for Sunlight (mp3)

"The Universe Is A Woman" - Treefight for Sunlight (mp3)

"They Never Did Know" - Treefight for Sunlight (mp3)

Reader Comments