BOOKS

BOOKS « In Which We Let In The World »

Thursday, October 4, 2012 at 10:17AM

Thursday, October 4, 2012 at 10:17AM

How and Why To Write

Writing advice is even older than writing itself. It never hurts to listen to how someone else perpetrates a similar crime, like wanting to witness a bank robbery committed by a close friend before embarking on the task. It's best to just give yourself over. If you reread your work too much, second guessing becomes de rigeur. Let go. Once your mind starts to connect with other minds, you begin to think in a similar fashion. Form is never more than an extension of something.

You can find the first four parts of this series here:

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, Robert Creeley, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Lyn Hejinian, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)

Rosmarie Waldrop

But it is not true that "nothing is given": Language comes not only with an infinite potential for new combinations, but with a long history contained in it.

The blank page is not blank. No text has one single author. Whether we are conscious of it or not, we always write on top of a palimpsest. This is not a question of linear "influence," but of writing as dialog with a whole net of previous and concurrent texts, tradition, with the culture and language we breathe and move in, which conditions us even while we help to construct it.

Many of us have foregrounded this awareness as technique: using, collaging, transforming, "translating" parts of other works. I don't even have thoughts, I have methods that make language think, take over and me by the hand. Into sense or offense, syntax stretched across rules, relations of force, fluid the dip of the plumb line, the pull of eyes...

Joyce Cary

It is, I suppose, a standing temptation for every artist to put technique first; especially if he be a good technician. Nothing gives so much pleasure to an artist as the successful fusion of his sense and form. And it is easier to take a form and give it some significance than to find a form for your meaning.

I sometimes think that Flaubert, that famous technician, suffered from choosing his form first. We know, in fact, that his friend George Sand protested against his manner of writing as if, as she said, he lived only for words. 'Your whole life is full of affection. You are the most convinced individualist. But no sooner do you touch literature than you become a wholly different man, a man who wants to annihilate himself.' She meant that Flaubert had the wrong theory of art, that he wished, as we should say, to live in an ivory tower, and devote himself to technical perfection; and his technique, clever as it is, sometimes seems to detach itself from his intention.

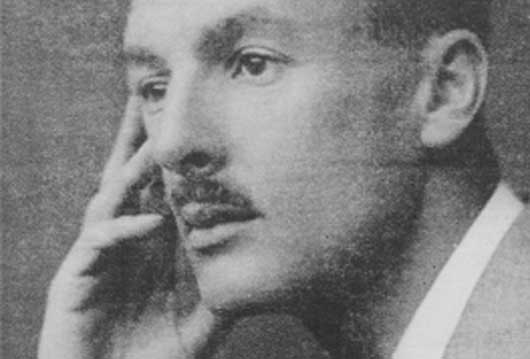

Fernando Pessoa

A strong artist kills in himself not only love and pity but the very seeds of love and pity. he becomes inhuman out of his great love of humanity - that love that prompts him to create art for man.

Genius is the greatest curse with which God can bless a man. It must be undergone with as little groaning and whining as possible, with as great a consciousness as possible of its divine sadness.

To attain a full reputation as a poet, the beginner must of course have his portrait published in fashionable papers and must see that paragraphs about himself, his habits, his whims and eccentricities are published in suitable journals. Now it must be clear that, for this to be well done, the learner must look like, and act as, a poet. As regards personal appearance, I think no one can deny that a thin, stooping gait is indispensable.

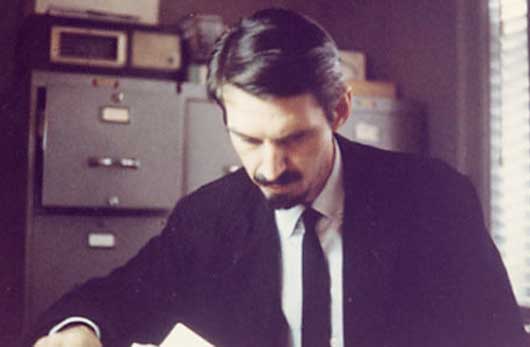

Martin Amis

Beyond middle age, I don't think writers are in competition anymore. After all, we're not all trying to write the same novel. We're all trying to write our own novel. In a sense, we're all trying to write a novel called, "The Way We Live Now," you know, the Trollope novel.

I don't think any interesting work of art can possibly be depressing - otherwise, King Lear would kill more people than cholera. If it's good, it's cathartic, and the reader feels purged and renewed.

Lewis Carroll

When you have made a thorough and reasonably long effort, to understand a thing, and still feel puzzled by it, stop, you will only hurt yourself by going on. Put it aside till the next morning; and if then you can't make it out, and have no one to explain it to you, put it aside entirely, and go back to that part of the subject which you do understand.

When I was reading Mathematics for University honours, I would sometimes, after working a week or two at some new book, and mastering ten or twenty pages, get into a hopeless muddle, and find it just as bad the next morning. My rule was to begin the book again. And perhaps in another fortnight I had come to the old difficulty with impetus enough to get over it. Or perhaps not. I have several books that I have begun over and over again.

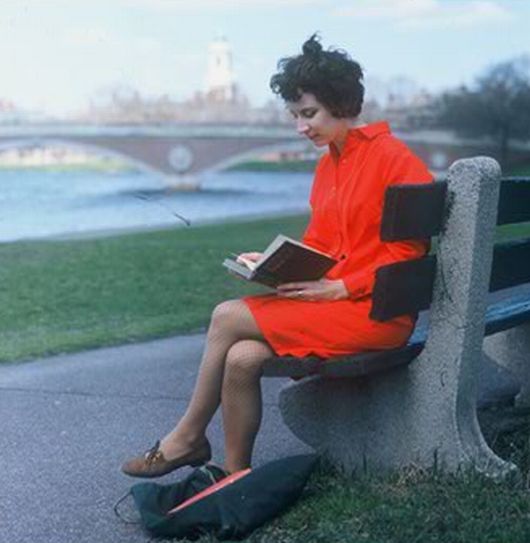

Margaret Atwood

1 Take a pencil to write with on aeroplanes. Pens leak. But if the pencil breaks, you can't sharpen it on the plane, because you can't take knives with you. Therefore: take two pencils.

2 If both pencils break, you can do a rough sharpening job with a nail file of the metal or glass type.

3 Take something to write on. Paper is good. In a pinch, pieces of wood or your arm will do.

4 If you're using a computer, always safeguard new text with a memory stick.

5 Do back exercises. Pain is distracting.

6 Hold the reader's attention. (This is likely to work better if you can hold your own.) But you don't know who the reader is, so it's like shooting fish with a slingshot in the dark. What fascinates A will bore the pants off B.

7 You most likely need a thesaurus, a rudimentary grammar book, and a grip on reality. This latter means: there's no free lunch. Writing is work. It's also gambling. You don't get a pension plan. Other people can help you a bit, but essentially you're on your own. Nobody is making you do this: you chose it, so don't whine.

8 You can never read your own book with the innocent anticipation that comes with that first delicious page of a new book, because you wrote the thing. You've been backstage. You've seen how the rabbits were smuggled into the hat. Therefore ask a reading friend or two to look at it before you give it to anyone in the publishing business. This friend should not be someone with whom you have a romantic relationship, unless you want to break up.

9 Don't sit down in the middle of the woods. If you're lost in the plot or blocked, retrace your steps to where you went wrong. Then take the other road. And/or change the person. Change the tense. Change the opening page.

10 Prayer might work. Or reading something else. Or a constant visualisation of the holy grail that is the finished, published version of your resplendent book.

Gene Wolfe

My definition of a great story is: One that can be read for pleasure by a cultivated reader and reread with increased pleasure.

Suppose, for example, that an editor has sabotaged one of your verbs because he thinks some noun you intended as singular is plural. For example you may have written, "A dieresis of fly specks warns us of double dealing." The editor, that lout, has of course revised your sentence to read, "A dieresis of flyspecks warn..." Understandable, you are tempted to pull a knife on him, but that is useless. The plural of knife is knives, which your editor thinks is another word altogether; you are bound to get into long, futile arguments about Charlemagne's turning the f into a v to correct the Julian calendar. No, the word you require is good old scissors, and you can drive home your point very nicely by opening your own, laying it (not them) on a sheet of paper, and tracing the outline in black crayon. You will need paper for this, of course, as well as the box of crayons, and while you have some, with the pencils, nuts, dictionary, wastebasket and all your other stuff, why not try a short story? Come to think of it you'll have to, to get in that line about dieresis.

Lyn Hejinian

The relationship of form, or "the constructive principle," to the materials of the work (its ideas, the conceptual mass, but also the words themselves) is the initial problem for the "open text," one that faces each writing anew.

Can form make the primary chaos (i.e. raw material, unorganized impulse and information, uncertainty, incompleteness, vastness) articulate without depriving it of its capacious vitality, its generative power? Can form go even further than that and actually generate that potency, opening uncertainty to curiousity, incompleteness to speculation, and turning vastness into plenitude? In my opinion, the answer is yes; that is, in fact, the function of form in art. Form is not a fixture but an activity.

Robert Creeley

Franz Kline said, "If I paint what I know, I bore myself. I paint what you know, I bore you. Therefore I paint what I don't know." He isn't saying that he paints what he doesn't know how to paint - but that he paints what he cannot conceptually enclose as intention. And he is doing it with consummate intelligence of the possibilities inherent in such an open situation - where what happens takes precedence over what 'should' happen - and with most alert perceptions. That's the point, for me at least, that the world be let in, that all the range of the art's powers of revelation, of doing something, be admitted. William Carlos Williams had a lovely qualification of the alternative: "Minds like beds, always made up..."

Williams - possibly in a somewhat defensive sense - said of a poem, that it was "a small or large machine made of words." The Abstract Expressionists insisted, with delight, that a painting was a "two-dimensional surface covered (or not) with paint" - and presumably the factual, physical situation of a film is equally to be insisted upon. I know that Brakhage likes to remind us that a 'moving picture' is a sequence of rapidly changing single, static images. If presently we are flooded with preoccupations of this kind, seemingly - I am thinking of the didatic, actually self-dramatic insistence on process and its physical occasions. I do believe, to say it, that life is its own reward, but I get absolutely irritable if it has always to be a situation of "look, Ma, I'm dancing!" I never did like dentists who explained what they were "going to do" to me.

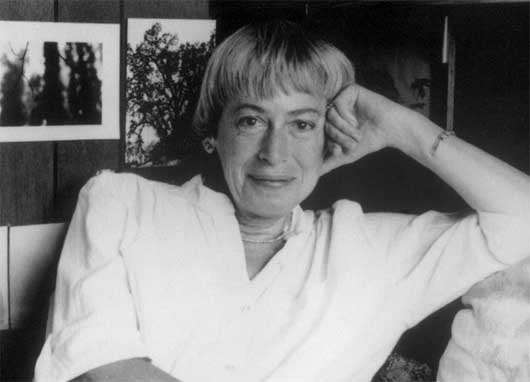

Ursula K. Le Guin

There is a limited number of plots (some say seven, some say twelve, some say thirty). There is no limit to the number of stories. Everybody in the world has their story, and every meeting of one with another begins another story. Somebody asked Willie Nelson where he got his songs, and he said, "The air's full of melodies, you just reach out..."

I say this in an attempt to unhook people from the idea they have to make an elaborate plan of a tight plot before they're allowed to write a story. If that's the way you like to write, write that way of course. But if it isn't, if you aren't a planner, don't worry.

How and Why To Write

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)

lyn hejinian,

lyn hejinian,  robert creeley,

robert creeley,  writing

writing

Reader Comments (2)