TV

TV « In Which You May Be A Lot Of Things But You're Not Alone »

Friday, July 20, 2012 at 10:41AM

Friday, July 20, 2012 at 10:41AM

So Long To Wait

by ALEX CARNEVALE

It all depends on whether or not the fragment of our life reveals the plan and material of the whole.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

One summer when I was very young my mother had a miscarriage and barely left her bed. My father had ordered a variety of magazines and products concerning her successful pregnancy and he told me to intercept them at the mailbox when I could. Every day she watched more than one soap opera, and since I had very little to do until Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles came on television, I watched them with her, leaning up against the foot of the bed.

I barely watch my actual television now, at least not in the way I did then. Because I knew so little of what made up the world, absorbing the details of how adult relationships worked became an endlessly fascinating activity. I was astonished by the way adults seemed to hold onto their relationships, since long term planning and the endless series of codas inherent in any soap storyline was anathema to my own experience. Indeed, in the children's television of the time, everything existed purely within the realm of an event, a happening, and afterwards the behavior of that moment was rendered incidental.

Watching The Real L Word still gives me the feeling I had upon seeing those soaps for the first time. The Showtime reality show has entered its third season of focusing on the lives of variously successful lesbians in the Los Angeles area, expanding its purview to consider Brooklyn lesbians as well. The Real L Word is the best reality show ever created, and I don't know that it's particularly close.

from left: Romi, Cori, Kacy, Lauren, Sara, Whitney, Kiyomi, Amanda, Somer

from left: Romi, Cori, Kacy, Lauren, Sara, Whitney, Kiyomi, Amanda, Somer

Some cultures, perhaps even most, revolve around men. The lives of the women on The Real L Word do not concern men in the slightest. This comes as something of a relief to me, because the novelty of the male form wore off around the fifteenth time I viewed my penis. Growing up almost all of my teachers were women, and the male teachers I encountered seemed impossibly different from men like my father, and that was difficult to reconcile. Although I had little knowledge of it at the time, many of the most significant teachers I had were lesbians.

The distinctive feature of 21st century life, especially in urban areas, is the degree to which it revolves around the lives of the female gender. This is taken to the complete extreme on The Real L Word. Some of the lesbians know and are friendly with men, but the vast majority of these men are gay, and even the ones that aren't dress like Robin and wear exaggerated eyeglasses.

It was easy to think of The Real L Word's milieu as a kind of other world until this season. I have never lived in Los Angeles; I went there once for a wedding but the ceremony was on a boat. I'd last about five minutes lingering in traffic. Even though John Cage says that waiting in lines is an opportunity to practice patience, this is a fucking lie.

Lauren

Lauren

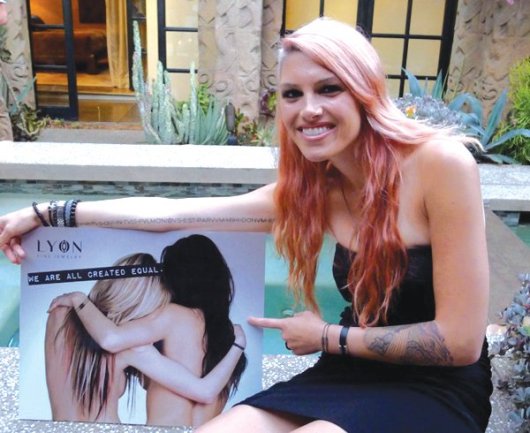

This third season of the show focuses on a bicoastal look at lesbian life; you'd be forgiven if you thought there was any other place in the universe. The existence of the New York lesbian is of course different from that of the Los Angeles lesbian. It is hard to quantify this exactly, but color scheme, facial expressions and hoodies all play a major role. In addition, a Los Angeles lesbian is over three times as likely to be a jewelry designer.

Lauren (pictured above) is one such individual. She is tall and a bit slack-jawed; her features are so completely distinctive that it's impossible to mistake the sight of her at any distance. Her jewelry resembles leeches or black prawns. Even though she does not really know Romi, the recovering alcoholic lesbian who was the star of The Real L Word's last season, she feels a budding rivalry with the show's narrow-faced antagonist. This is because she's been fucking Romi's also alcoholic ex-girlfriend Kelsey.

Lauren was living in a house with two women, but she evicted them because her best friend Amanda is moving from New York to live with her. "We're young and we can afford it," Amanda opines as she hoovers a cigarette. "It's something we've always wanted to do." She is very similar looking to Lauren except that she is shorter and wears less makeup when she goes out. There has always been a nascent sexual tension between Amanda and Lauren, but when they lived in the same city before, both were in relationships. Their significant others struggled to deal with the intimacy between the two best friends, and Lauren expects a romance to manifest, or at the very least sex when neither finds a partner.

KiyomiSex is where The Real L Word transcends the boundaries other television shows needlessly impose on their nonfictions. We see sex when it happens, as it happens. Not all of it, but enough to where we struggle to discern the difference between the tree and a drawing of a tree. A fight takes place, a woman comes home to see her girlfriend. Two people wake up, always surprised to see they share the same bed, and the mere novelty of their proximity leads to languorous sex. This is the simplest of human acts, and yet it never takes place in any of our fiction, except offscreen or in a completely unerotic montage.

KiyomiSex is where The Real L Word transcends the boundaries other television shows needlessly impose on their nonfictions. We see sex when it happens, as it happens. Not all of it, but enough to where we struggle to discern the difference between the tree and a drawing of a tree. A fight takes place, a woman comes home to see her girlfriend. Two people wake up, always surprised to see they share the same bed, and the mere novelty of their proximity leads to languorous sex. This is the simplest of human acts, and yet it never takes place in any of our fiction, except offscreen or in a completely unerotic montage.

It's not that the sex in The Real L Word is particularly titillating. Watching it, I rarely find myself the least bit turned on so much as empathically happy for the individuals involved in it, because for the most part they seem to genuinely care for each other. Watching Kiyomi perform cunnilingus in the shower becomes a moment as intimate for the audience as her girlfriend Ali, who moments before had been completely enraged. Sex in this fashion does not draw our attention to something else, it exists simply for its own sake. This is a lesson young men are never taught.

Whitney (left) and Sara

Whitney (left) and Sara

Most often nude on The Real L Word is the show's white, dreadlocked constant, Whitney. She has been the show's central character since it began, both because she knows every single lesbian in the greater Southern California area, and because she's dumped most of them. Whitney derives a certain energy from her interactions, and people seem to feed off this. Despite being a relatively usual looking person, lesbians are drawn to Whitney's brusque sexuality and introvert/extrovert personality, and whatever darkness underlies her unique social abilities. Yet they expect her to conform to a certain type, and when she shows them she is not entirely what they thought, instead of feeling deceived they experience a malingering pity towards her that is very easily confused with sexual attraction and even love.

There exists an entire house full of Whitney's ex-girlfriends: Jaq, Alyssa and Rachel. They console each other, endleslly discussing Whitney and her burgeoning long-term relationship with Sara. (Sara's name is pronounced Sada, for reasons I cannot impossibly imagine.) This woman has achieved what many could not — she has inspired Whitney to pursue a monogamous arrangement with her. This first coda for Whitney's life is shocking considering the nature of her past sex life, but it is the sort of surprise that happens very often on The Real L Word. It is akin to the feelings I experienced watching soaps with my mother: a complete alarm at the unfamiliar situations my favorite characters found themselves in. I never thought Zack Morris would get married, no more than I thought Donatello or Raphael had working reproductive organs.

Whitney and Amanda

Whitney and Amanda

I have always been fascinated by what happens to people when you are not there to witness what will become of them. As a child I read too many books and assumed the impression I had of the endings scheduled for literary characters was nothing like actual life. I have found over time that the only real difference between the endings of the fictional characters and their living counterparts is in the number of endings, not in the strangeness. The lesbians of The Real L Word astound me with their capacity for change, in the way they adapt so seamlessly to the changing contours of their lives. I never liked change, whether it was a new school, a new place or a new group of people, not because I did not enjoy the novelty of new friends or situations, but because it meant saying goodbye to the old.

Romi at the house of Whitney's ex-girlfriends

Romi at the house of Whitney's ex-girlfriends

Romi spent most of last season trying to stop drinking. The purpose of alcohol in her life was twofold: to lubricate her social interactions so she could enjoy going out in a large group, and to allow her to enjoy sex with her partner Kelsey. Each time she imbibed she was so inebriated that blacking out and not remembering her actions became a regular fixture of her evenings.

After Romi quit alcohol, she morphed into an irritable and quick-tempered woman. At the same time her sober self was more driven and focused on her relationships and career as a clothing designer. She constantly expressed her disgust with her girlfriend Kelsey's inability to hold a job, and if she came home and found Kelsey drinking a glass of wine, she exploded in a miasma of indignant rage. Television is absolutely the best way to fathom this kind of sea change.

It is revealed in the third season premiere that Romi has spent the past six months of her life in a relationship with a man, her ex-boyfriend Jay. When Romi finally works up the courage to tell a few of her lesbian friends about this development in her life (she's somewhat ashamed and also afraid of how they'll react to the news), she also brings up that she has been putting his penis in her mouth on a frequent basis. Her friends visibly shudder. Some of those who know Romi believe this is the ending to which her life has proceeded apace all along; others are convinced that this simply represents another avenue for Romi to get a disproportionate amount of attention for her behavior. The indeterminacy between these possibilities in her narrative contains all my own hopes and desires about what life might hold.

from left: Splinter, Raphael, Leonardo, April, Donatello, Michaelangelo

from left: Splinter, Raphael, Leonardo, April, Donatello, Michaelangelo

When I was a kid, I actually spent time wondering what happened to the Ninja Turtles when their television show went off the air. I even wrote short stories about their lives after Shredder and Krang were buried at the bottom of the ocean together in a gold-plated casket with all the foot soldiers. The turtles could not possibly exist in a state of continual adolescence — although I have to admit I found that an attractive ideal.

The ascent into maturity at first seemed to limit the capacity for change, since all the adults I knew when I was young seemed so completely static in comparison. Of course this was naive. I wondered chiefly what would happen to the intrepid reporter April O'Neil, friend to reptiles and their rodent master. In her old age she would speak movingly about the various intimacies she shared with these otherworldly creatures. The sewer was her Paris. It might have been confusing, if you knew her in both periods of her life, to decide which was the real April or when exactly her ending occurred. The question of what happens to the people you know after you stop knowing them never goes away.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. He is a writer living in Manhattan. He tumbls here and twitters here. He last wrote in these pages about Iris Murdoch. You can find an archive of his writing on This Recording here.

alex carnevale,

alex carnevale,  john cage,

john cage,  the real l word,

the real l word,  tmnt

tmnt

Reader Comments (6)

Then alarms would go off, Lex Luthor would attack, and the show would enter the predictable format panic---> battle---> victory which was completely uninteresting. The "conflict" represented the end of the show for me-- the ultimate anticlimax. How boring. I dreamed of one day watching an entire episode of just hanging out.

I think maybe this is similar to what you are describing (but I have never seen articulated). Nice work.

Well, at least you've done your research.