ART

ART « In Which Our Body Is Smashed On A Wooden Bus »

Tuesday, January 22, 2013 at 10:45AM

Tuesday, January 22, 2013 at 10:45AM

Spine and Back

by ELLEN COPPERFIELD

When Frida Kahlo was three, the Mexican Revolution arrived in full force. Her father was a European Jew, a photographer who fled his home country after his father married a reprehensible woman. Young Guillermo Kahlo suffered from frequent seizures in his new home of Mexico City.

Her mother, Matilde Calderon, was Guillermo Kahlo's second wife; his first had died in childbirth. Matilde did not love her husband, but she was already 24 and suitors were not exactly at the door. For the first few years of their marriage Guillermo was a taciturn, unhappy man. He never wanted to be in Mexico.

The girl's real given name was Magdalena. She went by Frida from the very first, spelling her name in the German fashion, Fride, until the Nazis came to power. Her older sisters were her primary caregivers.

In the revolution the Kahlos supported the Zapatas, feeding guerrillas when they could, but in the new government, her father's photographic commissions disappeared.

The family's new poverty was handled exclusively by Frida's mother, who was a devout Catholic. "She did not know how to read or write," Frida remembered later. "She only knew how to count money."

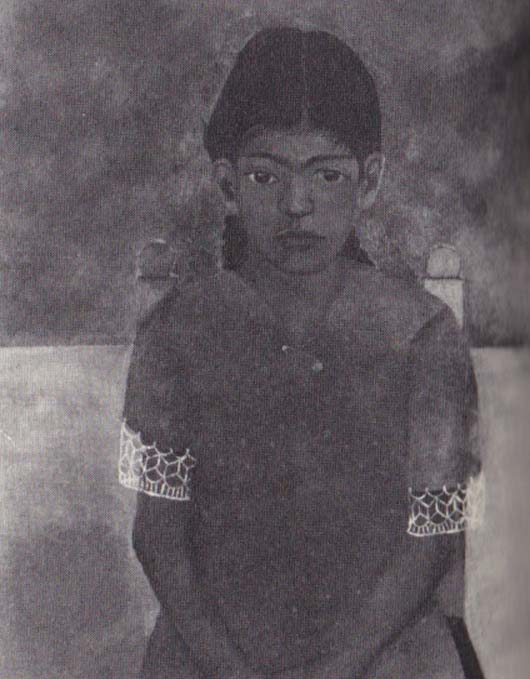

At the age of six she contracted polio. "It all began with a terrible pain in my right leg from the muscle downard," she said. "They washed my little leg in a small tub with walnut water and hot towels."

When she recovered, the prescription of physical exercise inculcated her father's interest in her. He had no son, and encouraged her to play soccer, wrestle and swim. She shucked off her illness, but as a tomboy she was made into a social outcast.

The closeness between the two extended to Frida's growing knowledge about art. It was a form of taking control. Her father also painted, and his canvases were painstakingly realistic scenes.

In 1922 she entered the National Prepatory School, the most prestigious institution of its kind in Mexico. Girls had only recently been admitted to these environs, and Frida was one of 35 individuals in a school of 2000. Unlike other students, she always wore a backpack.

with her own students

with her own students

She was also estranged from the other girls. They gathered on a second floor patio, she never gathered anywhere, just appearing unexpectedly like hepatitis. She found this new place fascinating and her photographic memory ensured she did not have to work very hard to pass her classes.

Diego Rivera had the run of the school. He was massively fat then, and she soaped stairs so he fell as a prank. She had some close boyfriends and wrote them letters as her primary means of communication. When she graduated, her job prospects were slim. Frida stayed busy, keeping accounts at a lumber yard to make ends meet.

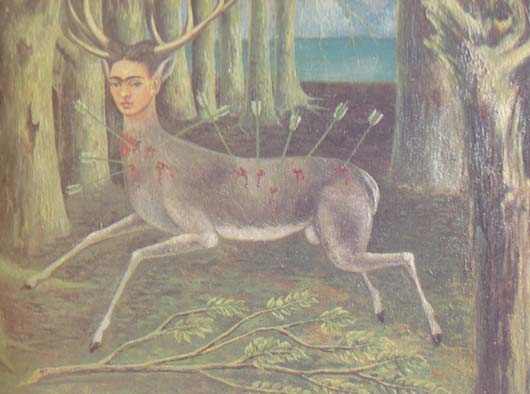

Then, in an event that would alter every day thereafter, she was riding a wooden bus crumpled by a trolley, and she was subdued under the wreckage. It was a slow, bracing kind of accident, born of fundamental stupidity. Her "first responders" removed a handrail that had gone so deeply into Frida that it emerged from her vagina. She survived after a few days where her life hung in the balance, but her spine and pelvis were broken.

She recovered in a derelict Red Cross hospital, with a ratio of one nurse for every twenty-five patients. She briefly regained the use of her legs in 1925 until some undiagnosed spinal fractures put her back in a full body cast. To entertain herself she drew her accident, but only in pencil.

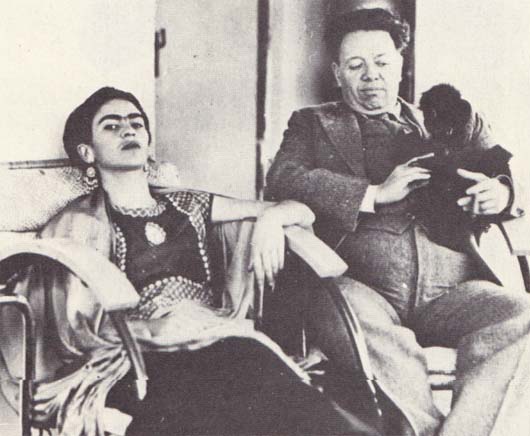

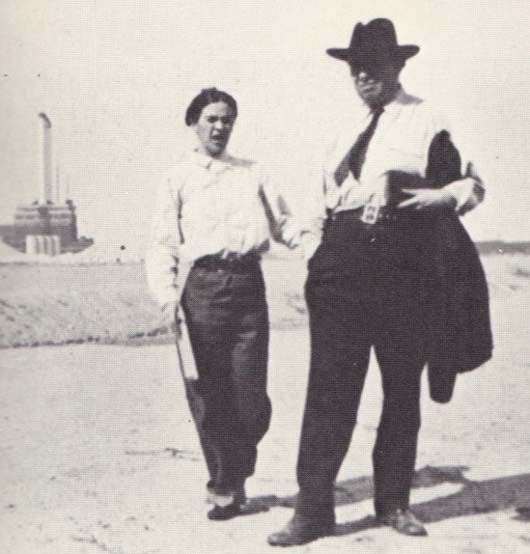

Frida married Diego Rivera, twenty years her elder, twice. He slept with other woman as a matter of routine, but seemed to view his wife in a somewhat different light. Her mother called Frida's new husband a "fat farmer." While she dealt with her first miscarriage, Diego enjoyed an affair with one of his assistants.

Expelled from the Communist Party, Diego and Frida took refuge in America. She found San Francisco an unfriendly place and struggled with her English. While Diego seduced the subjects of his portraits, she found consolation in the arms of women.

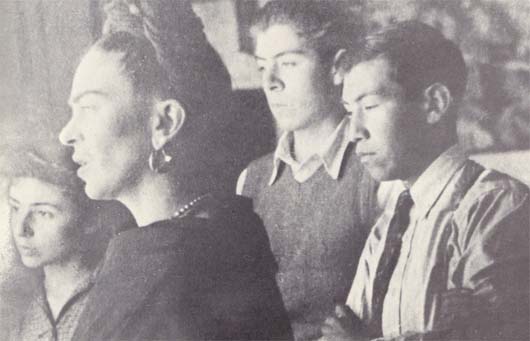

with Diego Rivera

with Diego Rivera

Back in Mexico, Diego planned two houses in San Ángel, one for Frida and one for himself., that would be situated next to each other for maximum privacy and maximum closeness. (This dream was realized later.) The two came to New York in the fall of 1931 when Frida's husband received a commission from the Museum of Modern Art. Detroit, in contrast, was a "shabby little village" where Diego planned to paint the assembly line as some kind of Marxist exemplar.

She miscarried again at Henry Ford's hospital. Her series of lithographs about this, titled Frida and the Miscarriage, showed her at all her most vulnerable moments. Her mother died of cancer.

Diego wanted badly to stay in America, but Frida preferred to return to Mexico. Finally out of money they returned to their native country in 1933. Diego took Frida's sister Cristina as the primary model for his nude paintings, and eventually his mistress. When his wife found out, she cut off her hair, had her appendix removed, and then underwent an abortion.

Her drinking became increasingly obliviating. She made peace with her husband and her sister after thinking it over carefully. To retaliate she took up with other male painters. She even seduced Leon Trotsky by speaking in a language his dowdy wife did not know: English.

Their flirtation faded until he was murdered with an ice pick. Frida and her sister were interrogated for fourteen hours.

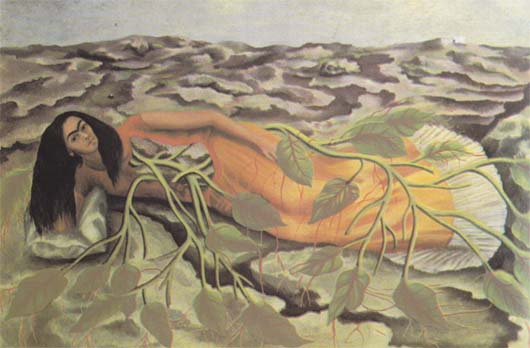

She divorced Diego and her work became the center of her life. Her shows in New York were helped by an admiring Julien Levy; in Paris she learned to hate Andre Breton with a passion unknown to her. She disliked being his pet.

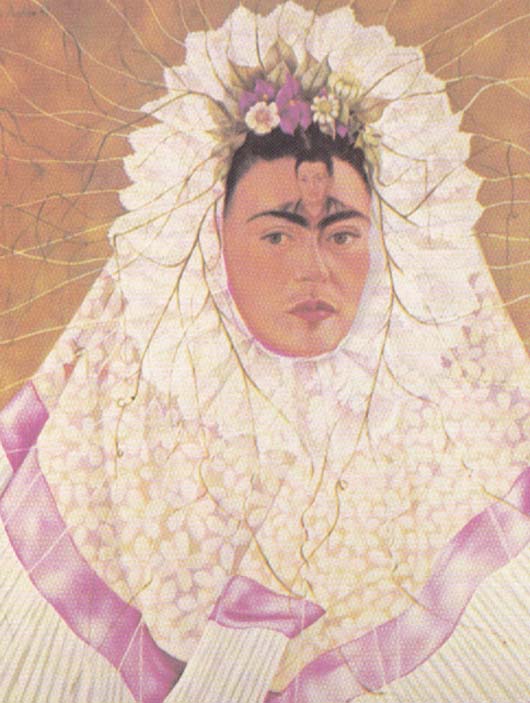

Viewing her paintings now, they seem utterly divorced from the surrealist moment. They are not fantastical creations - they are instead perfectly reasonable realizations of her own life. She resided in all of these places, and when she herself could not be in them, there was another woman, resembling her in almost every fashion, who could be made to take her place.

Ellen Copperfield is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in San Francisco. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She last wrote in these pages about Marlon Brando.

"Wonderful, Glorious" - Eels (mp3)

"Open My Present" - Eels (mp3)

Reader Comments (1)