ART

ART « In Which It Was Something We Cannot Explain »

Tuesday, March 5, 2013 at 10:44AM

Tuesday, March 5, 2013 at 10:44AM

My Chagall Memwah

by ALEX CARNEVALE

The Chagalls planned to return to Paris after the Second World War. They waited in New York, Marc and his wife Bella did, exhausted by its crowds and pollution, for their home in France to be free. Occasionally they stayed in a hotel in the Adirondacks to get away from the bustle. "Here the only Jews are God himself and us," wrote Bella Chagall.

To pass the time Bella penned her memoirs. (At this point in time they were not yet better known as memwahs.) Put down in her glorious Yiddish, she described her life in Russia before her family had been splintered apart and taken from her. She wrote for hours at her desk in her characteristic black dress. She had been afraid to tell her story before, despite encouragement from friends and family, because of her shyness. The Russia she reimagined then no longer existed.

Marc described his wife during their last months together.

All calm and deep presentiment. I can see her again from our hotel window, sitting by the lake before going to the water. Waiting for me. Her whole being was waiting, listening to something, just as she had listened to the forest when she was a little girl.

Bella died of strep throat six days after the American army liberated Paris.

+

"I don't recognize the world," Marc Chagall wrote after her death. In her biography of the artist, Jackie Wullschlager describes him turning his canvases to the wall. He wept uncontrollably during his wife's funeral, she tells us, shocking onlookers. As he dealt with her passing, news flowed in of relatives alive and dead in the war. Joy and grief intermingled freely. In his confusion he even addressed a letter to Joseph Stalin.

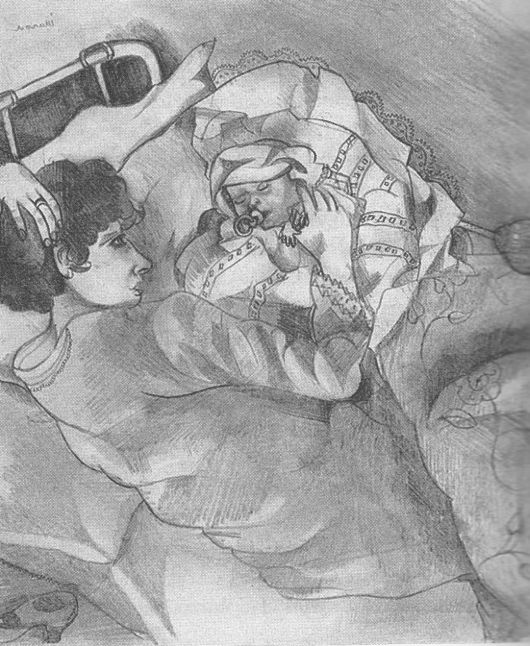

"Bella and Ida" 1916

"Bella and Ida" 1916

In tandem with his daughter Ida, Marc worked through his wife's papers. His daughter's many friends flowed through the apartment; on any given day as many as six languages were spoken there. Family members returned to the Chagall's Paris home, and there was naturally celebration for those who had survived. He wrote his friend Jean Grenier to say "I am very miserable at this time. I have lost the one who was everything to me - my eyes and my soul. If I continue to create and live it is because I hope to see France and the people of France again very soon." And to another: "I must cure myself of myself."

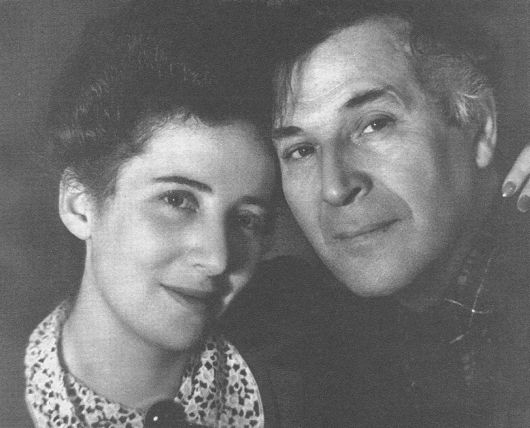

Ida and Marc, 1945

Ida and Marc, 1945

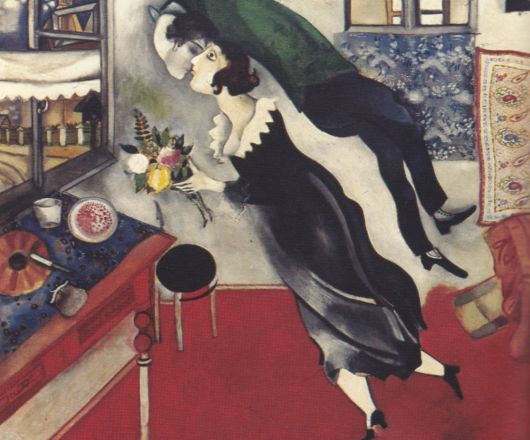

Spring reinvigorated Marc Chagall's creative drive. He had grown accustomed to working with his wife - he considered her opinion on his work invaluable. Bella's favorite color was green; sometimes when she sat for him she read passages aloud from the Old Testament in Yiddish. His many paintings of his wife are not simply portraits, they show Bella Chagall in the act: of gardening, of drinking, of existing as if her husband were only moments away from entering the scene. The empathy they display - albeit for an extension of himself and his love for her - nearly screams.

detail of "Bella with White Collar", 1917

detail of "Bella with White Collar", 1917

+

Ida Chagall met Virginia McNeil through a friend. Roughly the same age, Virginia required work: her husband was an insane, depressive drunk poet, and their five-year old daughter could not count on her father. The Englishwoman became the family's new housekeeper after repairing some socks, moving into the house with young Jean. Marc called the girl Genia because it sounded more Jewish.

Virginia McNeil could not help but be attracted to the older widower. Watching him paint, she took every opportunity to flirt, observing his shirtless attire during working hours. They hid the relationship from their daughters at first. When they vacationed in Sag Harbor, Virginia slipped in and out of Marc's room at night. This new, illicit relationship came out in his brush. "You must be in love!" his friend told him after seeing one particular painting.

Chagall did not get along with young Jean/Genia McNeil - he had never been fond of any children while they were children, not knowing how to relate to them. When his relationship with Virginia became more obvious and official, he demanded the girl be sent to boarding school in New Jersey. A month later, Virginia told him that she was pregnant.

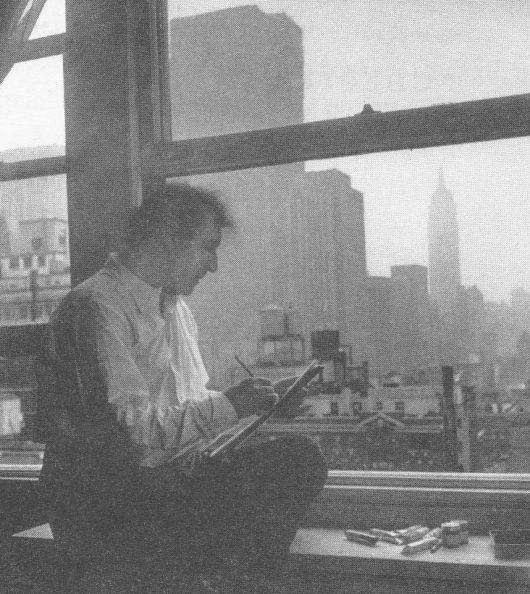

in New York, 1942Their relationship recollected his marriage when it could. Marc suggested Virginia convert to Judaism, but that never came to pass. He settled for having her attempt to make Russian food. Before the birth of David Chagall, Marc preemptively left for Paris, enlisting a friend to circumcize the baby. The day he sailed for Paris on the SS Brazil, Virginia sent for Jean to come home from boarding school exile. Chagall had not even left her enough money to pay the bills.

in New York, 1942Their relationship recollected his marriage when it could. Marc suggested Virginia convert to Judaism, but that never came to pass. He settled for having her attempt to make Russian food. Before the birth of David Chagall, Marc preemptively left for Paris, enlisting a friend to circumcize the baby. The day he sailed for Paris on the SS Brazil, Virginia sent for Jean to come home from boarding school exile. Chagall had not even left her enough money to pay the bills.

+

He had planned to only visit Paris, staying in the rooms his daughter rented for him. Instead he remained apart from his child for two years. Ida tried to explain to Virginia, with whom she continued to consummate an uneasy friendship, that her father had purpose in Paris: "People are waiting for him. Their expectation is something to be treasured, not despised. He owes Paris at least a semblance of return. It's like a gift; it must be given at the right time. Paris is Paris, beautiful, decaying, full of sweetness and bitterness."

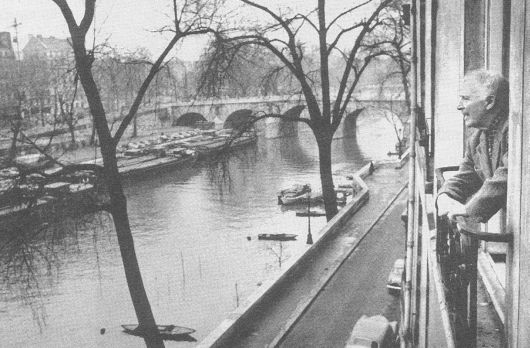

at the window of his apartment, 1958

at the window of his apartment, 1958

Eventually, he did miss Virginia. Maybe he had from the start, but between gallery events and lectures, there had been too much to occupy his attention. He brought her to Europe instead. The happy family:

Her essential non-Jewishness haunted their life. As a replacement for his wife the goy remained inadequate. His paintings continued to be concerned with Bella alone: they were constantly surrounded by the woman in heart and in mind. When he talked to Ida, they spoke in Russian, excluding Virginia from their conversations. This use of language replaced any lingering respect he could have had for Soviet Russia after seeing what the country had done to his friends and relatives.

Jean was constantly envious of her new brother; they sent the girl to live with her grandparents in England. Marc and Virginia attempted to live together in France, but Marc had lost the sexual desire which tied them so closely before. As Virginia flirted with their hippie neighbors and entertained ideas of other men, Marc spent most of his time with the famous artists he counted as friends.

In June of 1951 they went together to Israel. Both were uncomfortable in this foreign place; they barely touched each other. The distance was obvious. Virginia wrote, "I longed for some of the passionate tenderness that filled Marc's paintings, and it was something I couldn't explain to him. By nature, Marc was shy and undemonstrative in love. He talked a lot about love in general, he painted love, but he didn't practice it."

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. He is a writer living in Manhattan. He tumbls here and twitters here. You can find an archive of his writing on This Recording here. He last wrote in these pages about W.H. Auden coming to America.

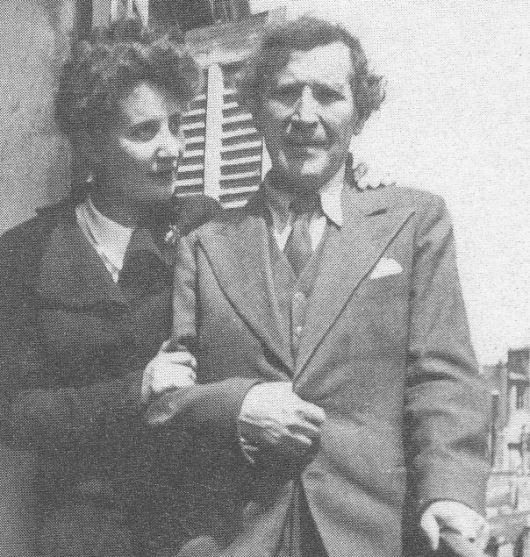

with Bella in Marseilles, 1941

with Bella in Marseilles, 1941

"Song For My Brunette" - Mathis Haug (mp3)

"Sad And Lonesome Day Blues" - Mathis Haug (mp3)

Is It More Important To Be A Great Artist Or A Great Person?

Ellen Copperfield & Frida Kahlo

Damian Weber & Andy Warhol

Isabella Yeager & Auguste Rodin

Timothy Stanley & Louise Bourgeois

Brittany Julious & Lorna Simpson

Sarah Wambold & Grant Wood

Alex Carnevale & Lee Krasner

Ellen Copperfield & Dorothea Lange

Elaine de Kooning & Mark Rothko

Alexandra Malmed & La Monte Young

Barbara Galletly & Willem de Kooning

Alex Carnevale & Fairfield Porter

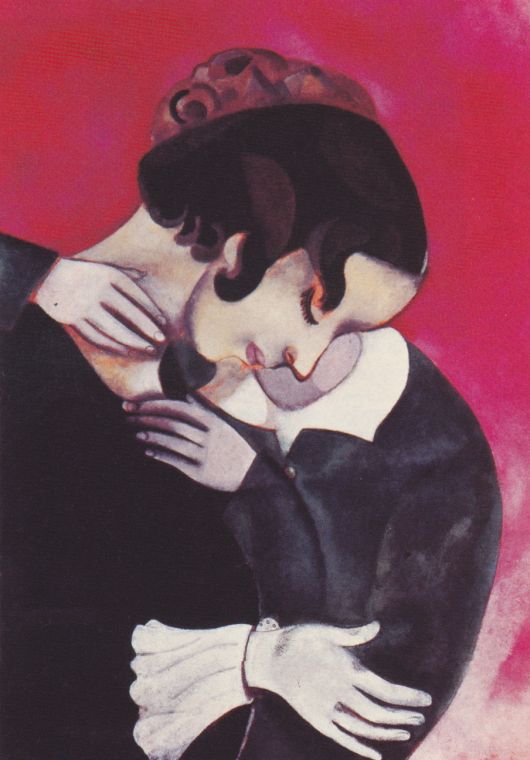

drawing of Marc and Bella as a young couple

drawing of Marc and Bella as a young couple

alex carnevale,

alex carnevale,  marc chagall,

marc chagall,  pablo picasso

pablo picasso

Reader Comments (1)

Re. this one "The empathy they display - albeit for an extension of himself and his love for her - nearly screams", what IS empathy towards self/love, actually? Creative/projective/self-reflexive empathy? What is empathy felt towards artistic representation/creation (one's own but also otherwise)?

Also interested in issues of morality/biography. Moral greatness seems not easily compatible with artistic greatness because - conventional notions of local "morality" require small scale selflessness, service and sacrifice, but ambitious artistic creation requires the opposite ---?

Anyway I shall think on these things. Thanks for a lovely article. It lingers like a phantom kiss.