FILM

FILM « In Which Boyhood Keeps Us In A State Of Perpetual Anxiety »

Monday, July 28, 2014 at 11:43AM

Monday, July 28, 2014 at 11:43AM

Familiar Story

by SARI EDELSTEIN

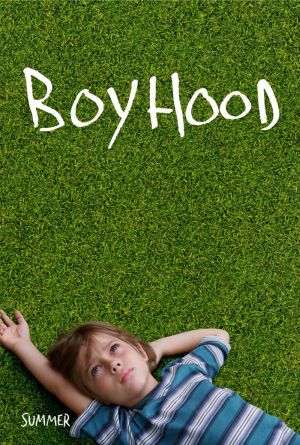

Boyhood

dir. Richard Linklater

165 minutes

Critics are swooning over Richard Linklater’s new film Boyhood, most notably because it took twelve years to film – see, for instance, Dana Stevens' rave. Linklater has claimed it was the longest shoot in film history. But this cinematic accomplishment does not serve a particularly novel take on adolescence or aging; instead, it offers a familiar story of coming-of-age as masculine disenchantment and growing older as decline.

Critics are swooning over Richard Linklater’s new film Boyhood, most notably because it took twelve years to film – see, for instance, Dana Stevens' rave. Linklater has claimed it was the longest shoot in film history. But this cinematic accomplishment does not serve a particularly novel take on adolescence or aging; instead, it offers a familiar story of coming-of-age as masculine disenchantment and growing older as decline.

Nominally about the boyhood of its protagonist, Mason Evans (Ellar Coltrane), Boyhood is actually about the effects of time more broadly, as it portrays the same actors over the course of twelve years. Thus, the film’s central subject is aging, and how years look. We see how twelve years register on the faces and bodies of the young actor as well as on the more familiar Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette, who play his parents.

The landscape of rural Texas – its canyons and vast expanses – affirm the power of time to change its subjects, to work deep ravines and crevasses into the earth. But while time renders the natural world ever more beautiful and mysterious, the film works hard to show that age has the opposite effect on people. According to this film, aging is not about progress or improvement, nor is it about the acquisition of wisdom. According to Boyhood, life involves nothing but a progressive winnowing away of idealism.

Though the hard-working mother of two, Olivia (Patricia Arquette), achieves some version of success (home ownership, graduate degree), she can’t find a decent husband or a modicum of financial stability. Moreover, the tenderness we witness with her children in the early scenes of the film dissolves into power struggles, nagging, and alienation.

Mason’s father, played by Ethan Hawke, is perhaps the only sympathetic man in the film, though he begins as a clichéd deadbeat dad. While he is absent for much of their childhood, he comes to desire true intimacy with his children. By contrast, Mason’s two stepfathers represent more conventional versions of “manhood," associated with alcoholism, violence, and emotional frigidity.

Boyhood dwells on the vapidity of traditional rites of passages; birthdays and graduations are rendered empty performances. When he turns fifteen, Mason is given a gun, a bible, and a suit and tie, the paraphernalia of the normative Southern man he is supposed to be. In one of the final scenes, his mother breaks down as her son leaves for college and sums up the film’s bleak view of aging when she semi-comically announces, “You know what’s next? My funeral!” Thus, far from celebration, rites of passage merely bring her closer to death. And Mason keeps viewers in a state of perpetual anxiety (avoiding car accidents, abuse, and injury by a hair’s breadth), as if to remind us that growing up is simply about not dying.

In this sense, Boyhood shares a sensibility with last summer’s sleeper coming-of-age film The Way, Way Back, which also rendered adulthood as an undesirable achievement. In that film, fourteen-year-old Duncan begrudgingly endures a summer vacation with his mother and her hostile boyfriend, Trent, at a beach house in a small New England town. To escape the claustrophobic climate of the beach cottage, Duncan finds refuge at a nearby waterpark whose loopy slides and swimming pools signal the film’s refusal to adhere to conventional ideas about linear development.

Where Boyhood portrays coming-of-age as disillusionment and fails to represent any alternative to the adulthood of the prior generation, The Way, Way Back challenges reigning ideas about how individuals experience the effects of time. In the film’s final scene, Duncan’s mother joins him in the “way, way back” of the family’s wood-paneled station wage, aligning herself with her son and his “backwards” way of seeing the world.

The movie thus ends in the same place it began; Duncan has not outgrown this childish status but has come to embrace it, reclaiming the lowest position on the hierarchy as a badge of honor and a preferable perspective. The Way, Way Back reminds us that growing older does not require one to conform to a life course rooted in stages and in the gradual assumption of normative gender roles.

Boyhood, on the contrary, is about the relentless stampede of years and their predictable and grim effects on individuals. Like the HBO television series Girls, Linklater’s movie makes a claim to universality with its title. But this boyhood is specific; it is a white, middle-class, Texan boyhood. In one scene, Olivia casually suggests to a young Latino landscaper that he go to college. To her surprise, the nameless character crosses her path years later at a restaurant; he has attended college and tells her, “You changed my life.” This surprising scene, strangely sentimental in the context of this cynical film, hints at the other boyhoods that might be imagined. Where Mason refuses to embrace the capitalist dictum that his parents, teachers, and supervisors relentlessly proffer, this young man seems to have wholly embraced the promise of the American dream. In a way, then, the movie acknowledges the specificity of version of boyhood it presents and implies that perhaps Mason’s anomie is itself a privilege.

Sari Edelstein is a contributor to This Recording. She teaches American literature at the University of Massachusetts-Boston. She doesn't tumbl or tweet. This is her first appearance in these pages.

"Ghostly" - Home Video (mp3)

"Calm Down" - Home Video (mp3)

Reader Comments (2)

Shayna

Well-written post and provocative post. I love the part about the use of the Texan landscape.

Questions: doesn't the final scene counter the idea of the "progressive winnowing away of idealism"? What is more idealistic than eschewing the technocratic university orientation and hiking out into the wilderness with new friends who are howling at the vast expanse? And that final look between two teenagers who can barely contain their smiles at the excitement of potential love? A portrait of the idealism of fresh love, if there ever was one.

And isn't a lot of the film supposed to be funny? Are you suggesting that the film actually endorses Mason's gift of a gun, a bible, and a coat and tie (which you astutely point out are the accoutrements of the traditional Texan man)? If anything, the film seems to mock this old-fashioned version of masculinity. Yet it doesn't just mock, because there are in fact tender, loving moments between Mason and his new step-grandfather. The point is: the relationships between Mason and the multiple lessons of manhood which come at him from all angles are nuanced and complex.

Yes, Mason's anomie is a privilege. And you're right, part of the privilege stems from his whiteness and, most of all, from his Americanness. But it is certainly not the privilege of unending wealth (as you would agree, I think).

Perhaps Mason sees the traditional rites of passage as empty performances (though I'm not even sure that this is true, since he seems more to be performing and trying on teenage angst for his friends . . . you know, as teenagers do). But certainly these rites of passage are not viewed as empty for the adults around him. And doesn't that seem pretty true to the world? That celebrations of youthful rites of passage are often more meaningful for the adults involved than for the youth? And in this film, these events are not entirely joyful. But this has nothing to do with the film being "cynical," I think. Rather, the film suggests that the past looms large over rites of passage. Families change, some relationships grow laden with sadness and regret, and some swell with hope. Mason's mom sure is sad at the end, but surely her narrative has not been one of full decline. Yes, adults are frail. Just like boys.

Perhaps adulthood in this movie is marked by looking backward. Boyhood, on the other hand, seems to look forward. That seems pretty idealistic.

p.s. Yeah, I'm posting anonymously. Sorry if that offends people. Me, I like the fact that the internet allows me to try on ideas that aren't automatically linked to my identity and subjectivity. So consider these ideas tried on! I look forward to any responses, etc.