BOOKS

BOOKS « In Which We Land Safely In The Ocean »

Tuesday, November 22, 2016 at 10:48AM

Tuesday, November 22, 2016 at 10:48AM

Saul Bellow's Letters to Women

Saul Bellow treated women no different in writing, it was somewhat divergent IRL. Easily irritated, Bellow stood on his principles at every possible moment, and usually gave his reasoning or admitted a lack of reasoning when appropriate. His guilt, you will notice, is always mitigated and never complete in itself. His personal writing matches his novel writing in almost every exactitude, except where it exercises a feigned or appropriate caution. There is insight there, but there is also a troubling, circling lack of definition. If he cannot find it in himself to address an emotion - anger, love, shame - he wields the silent treatment as a weapon of first and last resort. His first letter, perhaps suitably, concerns a woman he does not know.

December 14, 1973

Dear Evelyn

I was visiting with cousin Louie Dworkin the other night, and when he spoke of you I found that I could recall you vividly. You had one blue eye and one brown eye, and you were a charming gentle girl in a fur (raccoon?) coat. I thought you might like to know how memorable you were, so I asked cousin Louie (who loves you dearly) for your address, and I take this occasion to send you every good wish.

Saul Bellow

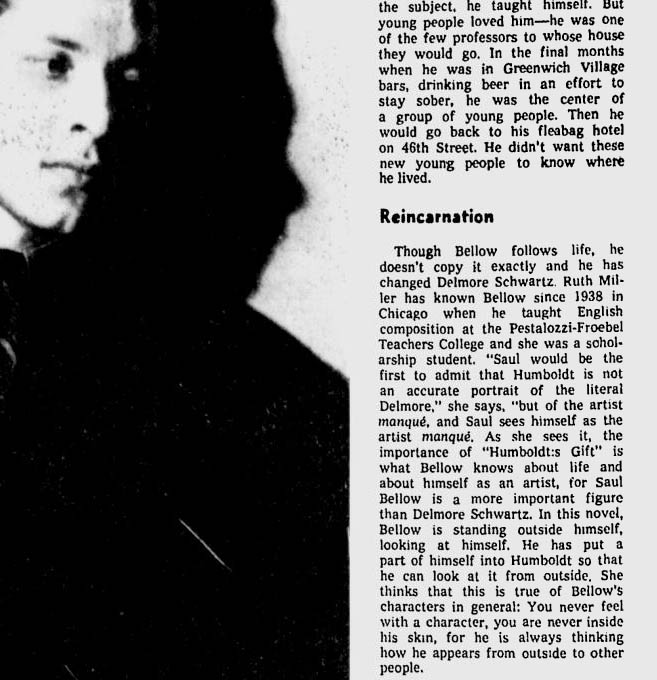

Ann Birstein, Alfred Kazin's ex-wife and author of 'What I Saw At The Fair'

Ann Birstein, Alfred Kazin's ex-wife and author of 'What I Saw At The Fair'

May 22, 1974

To Ann Birstein

My correspondence with Alfred was disagreeable, so I didn't associate you with it at all. You and I have never had disagreeable relations. I hope we never shall.

There used to be something like a literary life in this country, but the mad, ferocious Sixties tore it all to bits. Nothing remains but gossip and touchiness and anger. I'm past being distressed by it, I mean merely distressed.

So there it is! Nobody will speak for you to me. One of these days I hope we will have our own private conversation. It's been a long time.

As ever,

Saul Bellow

from 'Henderson the Rain King'

from 'Henderson the Rain King'

Bellow promised an interview to the young Oates, and followed up with this letter.

To Joyce Carol Oates

When I answered your letter of December 20th I said that I would be glad to do the interview-by-mail as soon as I sent off Humboldt's Gift, an amusing and probably unsatisfactory novel. Well, it went to the printer a few weeks ago and while I was waiting for the galleys I began to deal with your stimulating questions. Before I could make much progress the galleys began to arrive in batches so I have to put off the project again. When I was younger I used to think that my good intentions were somehow communicated to people by a secret telepathic wig-wag system. It was therefore disappointing to see at last that unless I spelt things out I couldn't hope to get credit for goodwill. I expect to be through with proofs in about two weeks and you should be receiving pages from me in about a month's time.

I'm not sure that you will want a photograph of me in your new journal. It seems that after I have finished a novel, I always want to write an essay to go with it, hitting everyone on the head. I did that when Henderson the Rain King appeared, and a very bad idea it was too, guaranteed misinterpretation of my novel. You shouldn't give readers two misinterpretable texts at the same time. And if you do publish my picture I will join the ten most wanted.

Yours most earnestly and sincerely,

Saul Bellow

Bellow was angry at his former student for her comment in the above article by Louis Simpson, and responded to her letter to him in the following fashion.

To Ruth Miller

That was a welcome letter. I haven't forgotten you, either. If I was your first teacher, you were my first pupil, and my heart hasn't altogether turned to stone. I've often reproached myself for my impatience towards you. I mitigate nothing by telling you that I'm like my poor father, first testy then penitent. One must free one's soul from these parental influences. Poor Papa's soul was his, after all, and mine is mine, and it's sheer laziness to borrow his behavior. We all do that, of course. He did it, too. Only he was too busy with life's battles to remove his father's thumbprints and cleanse the precious surfaces. We've been luckier. We have the leisure for it.

I read Simpson's piece in the Times before your letter came, and I didn't quite know how to deal with it. It was cheap, mean, it did me dirt. I had thought Simpson was paying no more attention to me than I've paid to him over the years. One can't look into everything, after all. I was indifferent to his poetry and it was only fair that he should pay no attention to what I wrote. I had no idea that he was in such a rage. But age does do some things for us (nothing comparable to what it takes away) and I have learned to endure such fits.

I don't ask myself why the Times prints such miserable stuff, why I must be called an ingrate, a mental tyrant, a thief, a philistine enemy of poetry, a narcissist incapable of feeling for others, a failed artist. Nor why this must be done in the Sunday Magazine for many millions of readers. Such things are not written about industrialists, or spies, or bankers, or trade-union leaders, or Idi Amin, or Palestinian terrorists, only about the author of a novel who wanted principally to be truthful and to give delight. It doesn't stab me to the heart, however. I know what newspapers are - and what writers are, and know that they can occasionally try to destroy one another. I've never done it myself, but I've seen it done, often enough.

Louie's hatred and my discomfort are minor matters, comparatively. He can't kill me. He's only doing dirt on my heart (by intention - he didn't actually succeed).

But I was upset to find you mentioned in his piece, and this is why I say that I didn't quite know how to deal with it. I wondered why you should find it necessary to testify against me and say that I was an artist manque. After many years in the trade, I'm well aware that the papers twist people's words and that at times their views are reversed for them by reporters and editors. But you were angry with me, and Stony Brook isn't exactly filled with my friends and admirers. Nor do I, from my side, think of Stony Brook as a great center of literary power in which a renaissance is about to begin, led by Kazin and Jack Ludwig and Louie. (Not that I've written reviews and articles about them.) So I didn't expect you to say kind things about me. But I didn't expect unkind things in print, and I was shocked by the opinion attributed to you that Humboldt was my confession of utter failure.

Louie I could dismiss. A writer who doesn't know quality when he sees it doesn't have to be taken seriously. A reader who doesn't see that the book is a very funny one can also be disregarded; one can only wonder why the deaf should attend concerts. But you I don't dismiss. And I thought, "I've steered Ruth wrong. What has this girl from Albany Park gained by ending up in Stony Brook? It is possible that she should have become one of these killers?"

I began to compose a few Herzog notes in my mind. But I wouldn't have sent any of them. You might not have been guilty of any offense. I do not defend myself anymore (in the old way). I have other concerns, now. But then your letter arrived. And you are what I always thought you were, and I am still your old loving friend,

Saul Bellow

April 12, 1979

To Ann Birstein

So Alfred thought that living with you was like living with me! I can't quite define my reaction, I never took the slightest sexual interest in him. The best I could do was to appreciate his merits. But esteem, you know, is far from attraction.

Hearing that he was at South Bend, I wrote to him in a Christian spirit (what a pity the Christians have a corner on the Christian spirit; isn't there some way to break the monopoly?) and gave him my telephone number and he called me, but we were both too much in demand to make a date, and then we were snowed in for some months, so we haven't seen each other yet. I'm going to try again now that strolling weather is nearly here.

No, I didn't know that you and he had finally separated. Inevitably, I had heard rumors, but gossip can never damage you, I don't mean anybody, I mean you specifically. After three divorces I can't say that I am ever pleased to hear of a divorce. In your case, however (you will forgive me if I tell you this), the delay must have been very damaging. But one can never really regret the course one's life has taken. There are always perfectly sound reasons why it couldn't have gone any other way. It's only my fondness for you (I remember still how Isaac and I were taken with you when you became Alfred's fiancee; I've never changed my mind) that makes me speculate sentimentally.

I take it as a sign of health that you have written a novel. I want to read it when Doubleday begins to send out copies.

Love,

Saul Bellow

Bellow wrote to Eleanor Clark after reading her novel Gloria Mundi.

October 10, 1979

To Eleanor Clark Reading Gloria Mundi made my return to Chicago considerably easier, lessened the culture shock. In the summer I am in Vermont, not of it (trees, skies, books, wife - an aesthetic sanctuary). Yours, the real Vermont, put things in perspective. There are connections between Wilmington and Chicago.

Reading Gloria Mundi made my return to Chicago considerably easier, lessened the culture shock. In the summer I am in Vermont, not of it (trees, skies, books, wife - an aesthetic sanctuary). Yours, the real Vermont, put things in perspective. There are connections between Wilmington and Chicago.

I admired your book. I took particular pleasure in the speed with which you got over the foothills to reach the necessary altitude, the place where things happen, the stripped-for-action, unencumbered plainness of the narrative. A complex subject presented without awkwardness, complication or rhetorical backing and filling. "Short views, for God's sake!" That's what Sydney Smith said. That's what the art of describing our breakdown demands. I took great satisfaction in your Vermonters, satisfaction of a different sort in the parachuting clergyman and the brat-maniacs. I was happy with your sketch of the Old Man, too. He took such pride in his culture. You remember his Céline essay, I'm sure, and the statements about the future of culture under socialism. Then the common man will be a Goethe, a Beethoven. He had me fooled. Alas for poor him, and poor us.

Alexandra still talks about the evening we spent together. It made [Saul] Steinberg's visit too. Next summer you come and dine with us.

Thanks for the book.

Yours ever,

Saul Bellow

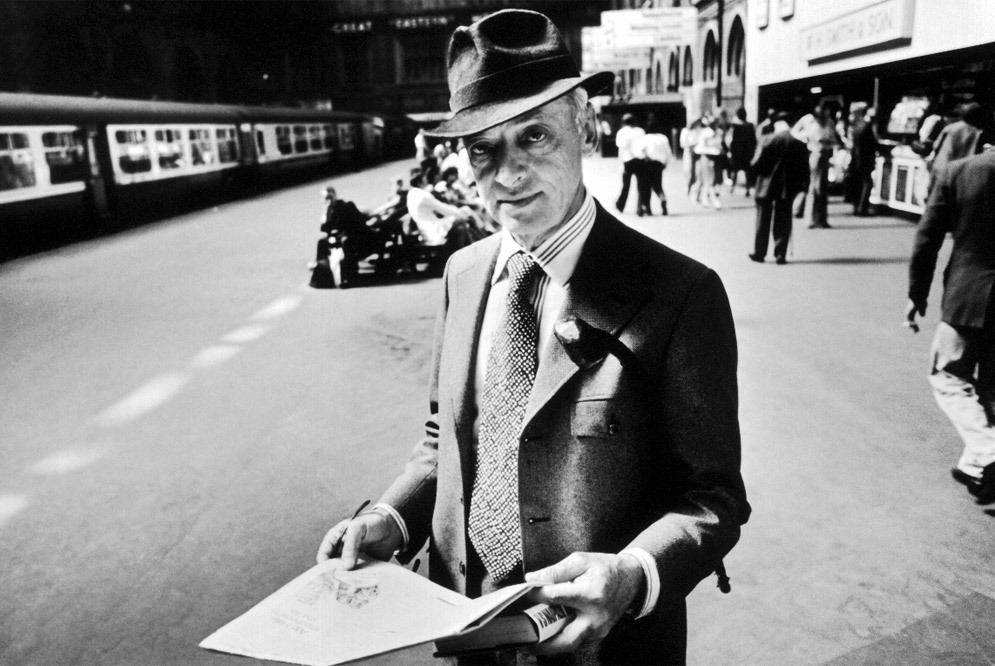

lecturing a class at the U of M

lecturing a class at the U of M

July 16, 1983

To Anne Doubillon Walter

You are probably used to my long silences. They aren't a sign of absent-mindedness really or of old-fashioned procrastination ("the thief of time"). I am simply incapable of "keeping up." I have never understood how to manage my time and now I have less strength to invest in attempted management. The days flutter past and this would be entertaining if I could compare them to butterflies, but there's nothing at all picturesque or cheerful about this condition. Rather it makes me heavy-hearted. Not a leaden state, just something permanently regrettable. Thus I hold your letter of March 3rd, which I intended to answer immediately because it contained a request. I wanted to tell you that a book about me vu par yourself would please me greatly, and of course you have my permission without restriction.

I thought of looking for you in Paris last September, but Flammarion and Co. left me no time for myself. I had nothing but the use of my eyes for looking past my interlocutors at the Seine. In my "spare" time I was presented to Monsieur Mitterand. He is a pleasant man, but I had some rather sharp exchanges with Mssrs. Debray and Lang [minister of culture under Mitterand]. I have a friend in Chicago who says that a minister of culture is a fatal clinical symptom. It tells you "culture is more abundant here." And if the French insist on using such American techniques for getting into the papers and onto the television screen, I don't see how they can then have the toupet to criticize the Americans. All they can say against the Americans is that they have made more progress in corruption. With a little help M. Lang will outstrip us.

For heaven's sake, Anny, don't worry about returning the loan. You will give me a good dinner one of these days, or send me some French books.

Dear old friend,

Saul Bellow

cynthia ozick

cynthia ozick

July 19, 1987

To Cynthia Ozick

At the Academy I was happy to see you, but then a wave of embarrassment struck me when I was reminded of my neglect and bad manners. You didn't mean to embarrass me when you reminded me that I owed you a letter (there had been a gap of two years). The embarrassment came from within, a check to my giddiness. It excited me to have so many wonderful contacts under the Academy's big top. Too many fast currents, too much turbulence, together with a terrible scratching at the heart; a sense that the pleasures of the day were hopeless, too boundless and wild to be enjoyed. There was such a crowd of dear people to see but I had unsettled accounts with all of them.

I should have written you a letter, it was too late to make the deaths of my brothers an excuse. Since they died, I wrote a book; why not a letter? A mysterious but truthful answer is that while I can gear myself up to do a novel, letters, real-life communications, are too much for me. I used to rattle them off easily enough; why is the challenge of writing to friends and acquaintances too much for me now? Because I have become such a solitary, and not in the Aristotelian sense: not a beast, not a god. Rather, a loner troubled by longings, incapable of finding a suitable language and despairing at the impossibility of composing messages in a playable key, as if I no longer understood the codes used by the estimable people who wanted to hear from me and would have so much to reply if only the impediments were taken away. By now I have only the cranky idiom of my books, the letters-in-general of an occult personality, a desperately odd somebody who has, as a last resort, invented a technique of self-representation.

You are the sort of person - and writer - to whom I can say such things, my kind of writer (without sclerosis in the matter of letters). I stop short of saying that you are humanly my sort. I have no grounds for that, I know you through your books, which I always read because they are written by the real thing. There aren't too many real things around. (A fact so well known that I would be tedious to elaborate on it.) You might have been one of the dazzling virtuosi, like [William] Gaddis. I might have done well in that line myself if I hadn't for one reason or another set my heart on being one of the real things. Life might have been easier in the literary concert-hall circuit. But Paganini wasn't Jewish. You probably see what I am clumsily getting at. I've been wending my way toward your Messiah and I speak as an admirer, not a critic. About Bruno Schulz I feel very much as you do, and although we have never discussed the Jewish question (or any other), and we would be bound to disagree (as Jewish discussants invariably do), it is certain that we would, at any rate, find each other Jewish enough. But I was puzzled by your Messiah. I puzzled myself over it. I liked the Hans Christian Andersen charm of your poor earnest young man in a Scandinavian capital, who is quixotic, deluded, fanatical, who lives on a borrowed Jewishness, leads a hydroponic existence and tries so touchingly to design his own selfhood. But when he is challenged by reality, we see the worst of him; nine times nine devils (to go to the other Testament for a moment) rush into him, and in his last state, because he is not the one and only authentic Schulz-interpreter, he becomes a mere literary pro, that is, a non-entity. I read your book on the plane to Israel, and in Haifa gave my copy to A. B. Yehoshua. He wanted it, and I urged him to read it. So in writing you, I haven't got a text to refer to, and must trust my memory or the memory of my impressions. When I read it I was highly pleased. When I thought back on it I felt you might have depended too much on your executive powers, your virtuosity (I've often passed the same judgment on myself) and that you wanted more from your subject than it actually yielded.

You probably see what I am clumsily getting at. I've been wending my way toward your Messiah and I speak as an admirer, not a critic. About Bruno Schulz I feel very much as you do, and although we have never discussed the Jewish question (or any other), and we would be bound to disagree (as Jewish discussants invariably do), it is certain that we would, at any rate, find each other Jewish enough. But I was puzzled by your Messiah. I puzzled myself over it. I liked the Hans Christian Andersen charm of your poor earnest young man in a Scandinavian capital, who is quixotic, deluded, fanatical, who lives on a borrowed Jewishness, leads a hydroponic existence and tries so touchingly to design his own selfhood. But when he is challenged by reality, we see the worst of him; nine times nine devils (to go to the other Testament for a moment) rush into him, and in his last state, because he is not the one and only authentic Schulz-interpreter, he becomes a mere literary pro, that is, a non-entity. I read your book on the plane to Israel, and in Haifa gave my copy to A. B. Yehoshua. He wanted it, and I urged him to read it. So in writing you, I haven't got a text to refer to, and must trust my memory or the memory of my impressions. When I read it I was highly pleased. When I thought back on it I felt you might have depended too much on your executive powers, your virtuosity (I've often passed the same judgment on myself) and that you wanted more from your subject than it actually yielded.

It's perfectly true that "Jewish Writers in America" (a repulsive category!) missed what should have been for them the central event of their time, the destruction of European Jewry. I can't say how our responsibility can be assessed. We (I speak of Jews now and not merely of writers) should have reckoned more fully, more deeply with it. Nobody in America seriously took this on and only a few Jews elsewhere (like Primo Levi) were able to comprehend it all. The Jews as a people reacted justly to it. So we have Israel, but in the matter of higher comprehension - well, the mental life of the century having been disfigured by the same forces of deformity that produced the Final Solution, there were no minds fit to comprehend. And intellectuals are trained to expect and demand from art what intellect is unable to do. (Following the foolish conventions of high-mindedness.) All parties then are passing the buck and every honest conscience feels the disgrace of it.

I was too busy becoming a novelist to take note of what was happening in the Forties. I was involved with "literature" and given over to preoccupations with art, with language, with my struggle on the American scene, with claims for recognition of my talent or, like my pals of the Partisan Review, with modernism, Marxism, New Criticism, with Eliot, Yeats, Proust, etc. - with anything except the terrible events in Poland. Growing slowly aware of this unspeakable evasion I didn't even know how to begin to admit it into my inner life. Not a particle of this can be denied. And can I really say - ”can anyone say" - what was to be done, how this "thing" ought to have been met? Since the late Forties I have been brooding about it and sometimes I imagine I can see something. But what such brooding may amount to is probably insignificant. I can't even begin to say what responsibility any of us may bear in such a matter, in a crime so vast that it brings all Being into Judgment.

Metaphysical aid, as somebody says in Macbeth (God forgive the mind for borrowing from such a source in this connection), would be more like it than "responsibility"; intercession from the spiritual world, assuming that there is anybody here capable of being moved by powers nobody nowadays takes seriously. Everybody is so "enlightened." By ridding myself of a certain amount of enlightenment I can at least have thoughts of this nature. I entertain them at night while rational censorship is sleeping. Revelation is, after all, at the heart of Jewish understanding, and revelation is something you can't send away for. You can't be ordered to procure it.

Some paragraphs back I said that you didn't seem to be getting what you really wanted from your Messiah novel. I can't think that I would offend you by speaking as I speak to myself. I have often rushed into the writing of a book and after thirty or forty pages, just after taking off, I felt that I had made a crazy jump, that I had yielded to a mad convulsion, and that from this convulsion of madness, absolutely uncalled-for and self-generated, I might never recover. At the start the fast take-off seemed such a wonderful and thrilling exploit. I believed in it still. But could I bring it off, would I land safely or fall into the ocean? I experienced the same anxiety in the middle of your novel (the Mediterranean below). You would be fully justified in calling this a projection and turning it against me. Anyway, I did have the sensation of turbulence, a dangerous air-storm. I felt you were brilliant and brave at the controls.

With best wishes,

Saul Bellow

Saul Bellow: Letters was edited by Benjamin Taylor and you can purchase it here.

Reader Comments