ART

ART « In Which Georges Braque Survives Multiple Wars »

Thursday, February 16, 2017 at 10:11AM

Thursday, February 16, 2017 at 10:11AM

A Break From All That

by ALEX CARNEVALE

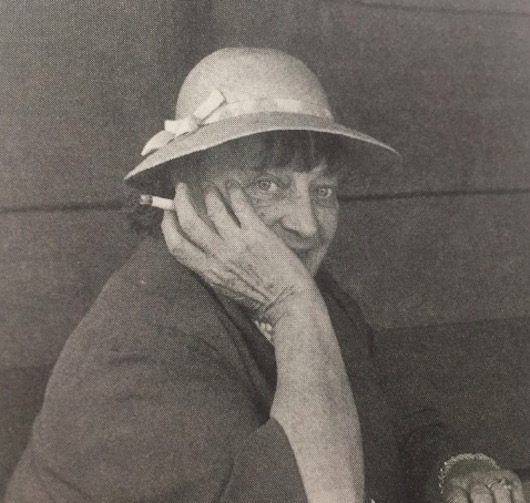

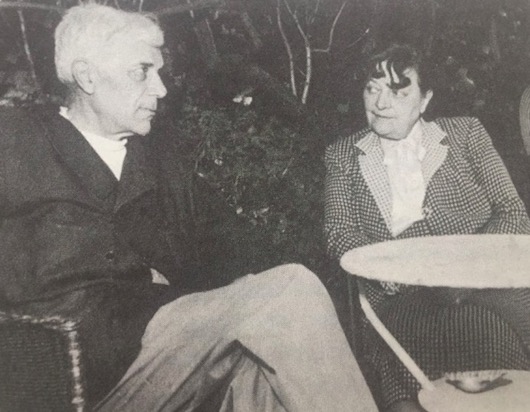

As he had for André Derain, Pablo Picasso chose Georges Braque's wife. Marcelle Vorvanne had modeled for other painters, including Modigliani, and had many cheerful anecdotes about doing so. She loved to drop nicknames on unsuspecting artists, terming Max Jacob "the magus." Her mother was an upholsterer, her father was absolutely missing. Madame Vorvanne was a tiny, stout woman with a low center of gravity; her frequent donning of a large hat made her look something like a striped or patterned turtle depending on her mode of dress.

Marcelle's birth name was Octavie, but she discarded it with much else. Reinventing yourself in Europe at this time was not terribly difficult, and she did it more than once. While Braque was a domineering type, he did not mind having a wife with her own mind. Marcelle was expert at giving people exactly what they wanted or needed. Her major tool of benign manipulation was food and drink; after a conversation with Marcelle, participants frequently felt undone.

In the first year of their dating, Braque was still keeping time with a courtesan he had known since boyhood, Paulette Philippi. Madame Philippi ran an opium den in Paris, and the drug would eventually ruin her good looks and sour Braque's view of her. Braque took Paulette to dinner and sometimes lectures, but he felt his heart moving towards Marcelle. When he returned from an uneventful bout of required military service in 1922, he and Marcelle moved into a double apartment in Paris. She continued calling him by his last name for the rest of their lives.

Marcelle usually went to church alone, which is not to say Braque had no faith in the almighty. He did avoid the chapel in Marseilles when they were summering. "It's probably because I know it too well," he said, "but it bothers me that when I go to the House of God it's Matisse that lets me in." Despite their cohabitation, the two would not be officially married until fifteen years later.

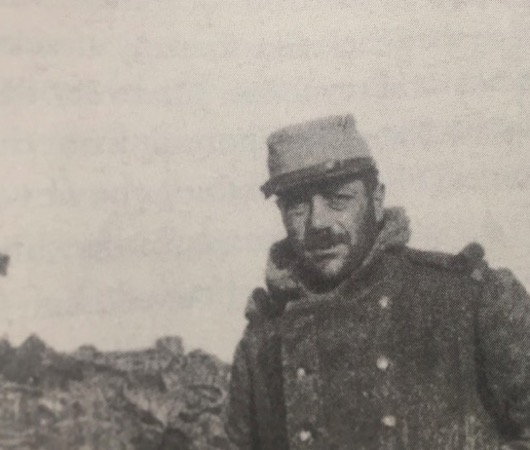

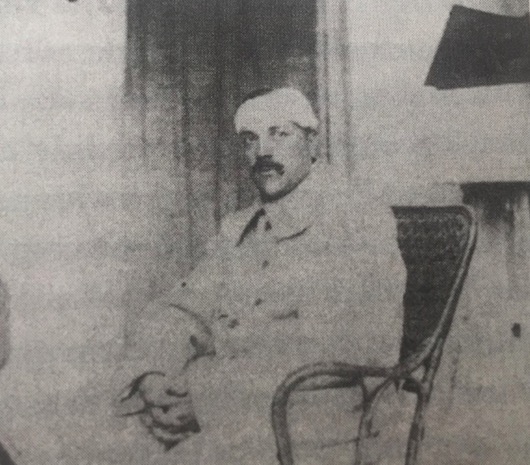

By 1914 the war was on. Braque and Derain were both immediately transferred to the front. Picasso took them to the station, writing fallaciously, "On 2 August 1914 I took Braque and Derain to the station at Avignon. I never saw them again." In the thick of the fight, Braque was awarded the Croix de Guerre and appointed Chevalier of the Legion of Honor.

In a battle at Neuville-Saint-Vaust, Braque was struck in the head. He became temporarily blind, a condition that was relieved by trepanning two holes in his skull to relieve the pressure. "I was afraid of finding him so badly wounded," Marcelle wrote, "that I would not be able to hide my despair." Braque would spend month after month under the care of doctors, during which time he could not even think of returning to his studio.

Picasso and Braque reunited, but as close as they had been before the war, they never got back to where they were. Picasso was deeply troubled by his own avoidance of battle, and remarked to Gertrude Stein, "Will it not be awful when Braque and Derain and all the rest of them put their wooden legs up on a chair and tell about their fighting?" Pablo was an all-around disgusting man.

Return to painting was slow for Georges. It took him until he received his full discharge, after two solid years of convalescence, to think of proceeding past still-lifes. "Survival does not erase the memory," he wrote.

He looked differently at those who had avoided combat: Gleizes and Picibia, Delaney and Duchamp. Even his closest friend. While Braque was fighting for his country, Picasso had become famous and rich. Still serving in the war, Derain looked down on them both.

A short essay of aphrorisms published by Braque in Nord-Sud helped him regain his creative compass and was variously praised and ridiculed by observers. Picasso and Derain in particular thought that "Thoughts and Reflections on Paintings" was nonsense, but it holds up somewhat better today:

In art, progress does not consist in extension, but in the knowledge of limits.

Limitation of means determines style, engenders new form, and gives impulse to creation.

Limited means often constitute the charm and force of primitive painting. Extension, on the contrary, leads the arts to decadence.

New means, new subjects.

The subject is not the object, it is a new unity, a lyricism which grows completely from the means.

The painter thinks in terms of form and color.

The goal is not to be concerned with reconstituting an anecdotal fact, but with constituting a pictorial fact.

Painting is a method of representation.

One must not imitate what one wants to create.

One does not imitate appearances; the appearance is the result.

To be pure imitation, painting must forget appearance.

To work from nature is to improvise.

One must beware of an all-purpose formula that will serve to interpret the other arts as well as reality, and that instead of creating will only produce a style, or rather a stylization…

The senses deform, the mind forms. Work to perfect the mind.

There is no certitude but in what the mind conceives.

The painter who wished to make a circle would only draw a curve. Its appearance might satisfy him, but he would doubt it. The compass would give him certitude. The papiers collés in my drawings also gave me a certitude.

Trompe l’oeil, is due to an anecdotal chance which succeeds because of the simplicity of the facts.

The pasted papers, the faux bois— and other elements of a similar kind— which I used in some of my drawings, also succeed through the simplicity of the facts; this has caused them to be confused with trompe l’oeil, of which they are the exact opposite. They are also simple facts, but are created by the mind, and are one of the justifications for a new form in space.

Nobility grows out of contained emotion.

Emotion should not be rendered by an excited trembling; it can neither be added on nor be imitated. It is the seed, the work is the blossom.

I like the rule that corrects the emotion.

Derain in particular was contemptuous of the publication. "I’m staggered by the aphorisms of Lieutenant Braque,” he wrote to his wife. “I even feel sorry for him, I have to say. What a filthy journal! He doesn’t see that the others are using him. I’d like to know what the General of Cubism thinks of it. As a reflection, he doesn’t exactly strain himself... I can’t help thinking about Braque’s nonsense. It’s so appallingly dry and insensitive. It manages to combine fanaticism with some initial omissions. One needs centuries of painting, good and bad, for or against, in order to have an idea about art. It regulates the imagination."

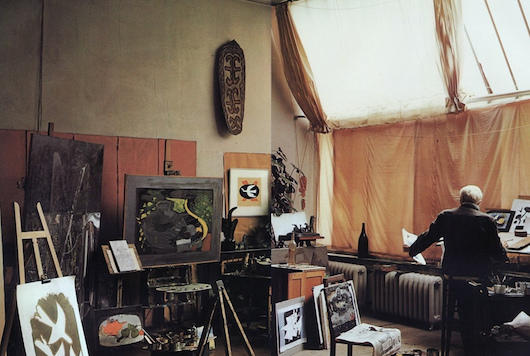

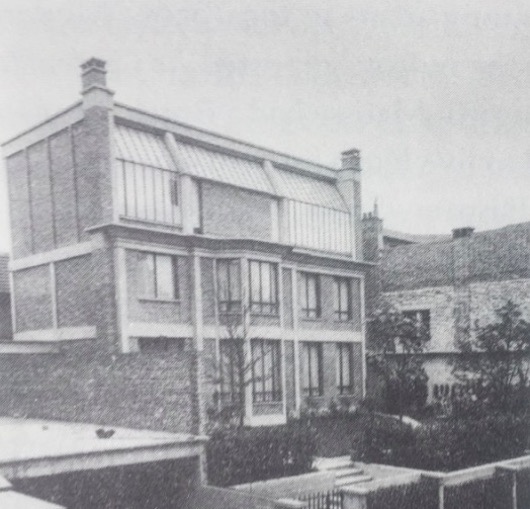

Along with the essay, a new spate of paintings followed and sold for obscene amounts. This allowed Braque and his wife to move to Montparnesse, where they commissioned the building of a house. Braque's studio took up the entire top floor of this magnificent, modern domicile. Servants filled the new home: a cook, a chaffeur. Marcelle ensured the walls were mostly yellow, the color which did not disturb her husband's restored and fragile vision.

The second World War smashed this reverie. The Braques fled Paris, meeting the Derains south of Toulose. Eventually, however, they would be able to return to their home, finding it had been used as a German officers' quarters. (Only Georges' accordion was missing.) Derain visited Germany as a honored guest of the Nazis, accepting commissions from the party.

Braque refused all entreaties from Berlin. He did leave his home in order to show his face at the funeral for Max Jacob, who had died on the way to the extermination camp at Treblinka.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording.

Reader Comments