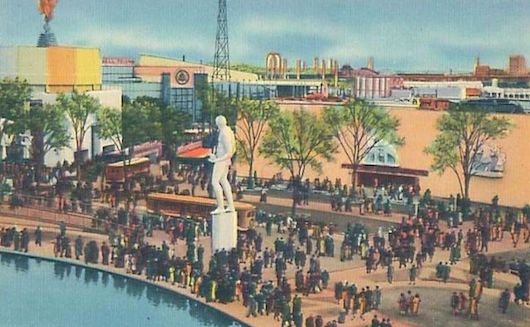

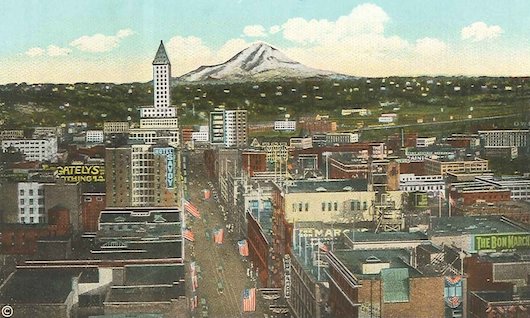

photo by thomas bollier

photo by thomas bollier

Before It Went Cold

by LEAH BUCKLEY

I’m not telling the whole story. There are intentions to which I am blind, which have almost certainly dictated that certain parts of the truth have been be occluded. I can’t tell you which parts, because I am engaged in hiding them from myself. So I’ll tell a story as if it were true, and hopefully it will hold together by some mutual tensions of its component parts.

Pete and I met early in the school year at a party. It was cold for October, but the room was so warm that the windows dripped with condensation like the walls of a shower. I can remember noticing his body first, seductive with a drumming energy.

“Good evening.” His teeth were surprisingly white for a musician, and square. His hooded drunk eyes slipped open and closed around the room until they landed on me.

“I’m sorry, I don’t think I know you,” I replied. It was a lie; I saw him almost everyday in the back of the library. McGill had a strict no-shoes policy to protect the library’s wooden floors, and I blushed, realizing that I even recognized the socks he was standing in now. “And what’s the story with the dog tags? Are you planning on dying in battle?”

“If I die, it will be doing my duty, baby.” He swung a leg over the top of the grubby couch and climbed down next to me. The corroding leather sagged and our bodies edged together. I breathed in his smell – nicotine and old spice.

“I’ll tell you what though,” he smiled at me with those big white teeth. “I’m bored to death here.”

That night I felt so alive I could barely breathe. We left the party together and he kissed me hard in the bitter winter cold. I wanted more of him, and had to fight a compulsion to scream. As he unlocked his door I tried to slow my breathing. Entering the tight stairwell, a wave of heat rose from his body in front of me on the stairs. Shadows fell over us as we wrestled in the darkness. Mystery made me hungry and my hands reached for every torrid part of him, felt the weight of him, untamed and rapacious. His dog tags swung from his neck and the cold metal hit my lips. I grabbed a hold of them, pulling him closer. My sense of time and space refracted, and everything collapsed into this minute.

photo by thomas bollier

photo by thomas bollier

I woke up to the taste of metal in my mouth. I was jarringly sober and naked, breathing in the unfamiliar smell of his apartment, moist, sultry and far from fresh. He stirred and I slowed my breathing, allowing only my eyes to slit back and forth. Who was this man? His bedroom didn't tell much. A basement apartment, it was claustrophobic and sunken, with a tiny window above the bed that looked out onto the ankles of passersby. His bedside table hosted an array of things and I began to conjure up an idea of him. This was a man who chewed spearmint gum, and had a sewing kit. He owned an antique portrait of a woman propped up on the floor next to crumpled up athletic shorts. He read Descartes in French, and bookmarked passages with guitar pics. He was also a heavy sleeper, indifferent as I slunk out of the bottom of the bed against the wall. As I tiptoed up the stairs, giddy from my escape, I began to piece together the night. Unwittingly, I’d already started crafting a story.

I woke up beside him the next night, and the night after. Everything about this romance felt novel, and Pete glistened with newness. I was obsessed with the way that I must look to him, and would glance at myself in windows as we walked together to try and see what he saw. I loved the way he said my name. His voice had an exotic color, not the flat metallic tone of the Great Lakes, with it’s clear hard r’s and absence of theatricality.

It was cold out now, the bitter cold of a Montreal winter. I stood in his doorway peeling off layers covered in snow, and dumped my boots in the corner. Pete strode over and pulled out a clear plastic baggie. “You wanna?” He placed two white pills onto my palm. Asking what they were would only reveal my innocence, so instead I looked into his beautiful bright eyes and swallowed them down without hesitating. He laughed and kissed me. “You have to come see our new strobe light.”

photo by thomas bollier

photo by thomas bollier

I sprawled out upside down on his roommate's bed, my arms cactused out and blood rushing to my head. Blue pink and purple lights rushed across the ceiling. I had started to feel a great pull on my heart, as though gravity had taken a hold of it, but didn't stop with a gentle downward force. It pulled in all directions, leaving me paralyzed. Where was Pete? He’d disappeared and I needed him. I was starting to panic, and even with my eyes squeezed closed I couldn't turn off the swirling lights. I opened my eyes and watched their pattern unfold above me, trying to make out voices above the booming techno. Then his face appeared above me. He sat down cross legged and cradled my head upside down in his lap. From this angle, I noticed a nick under his chin from a razor, and could smell the cigarettes on his worn in jeans. “Kiss me,” he said, and I flipped over onto my belly. I closed my eyes and pressed my lips to his. They felt so perfect, so smooth, I almost couldn't stand it. This was an impossible world I’d entered, in which I could give everything I had to him, but lost nothing of myself.

It was a winter of firsts: first high, first quiet come down, first pull of addiction, first love, first impassioned goodbye. Falling in love is spectacular, so much so that it necessitates a rapt consciousness. I was so busy jumping, falling, diving into Pete that I forgot to notice him, his lifetime of sorrows and beautiful triumphs. My memories of those months exist inside a teacup amusement ride; I’m sitting on the ride in focus, and he’s somewhere out there, a blur.

I think I remember the moment when things started to go south, but I can’t be sure.

“I know how to tell a joke,” Pete says absentmindedly. “You can’t telegraph the laugh.”

“What’s the joke?” I ask.

“That was the joke. You didn't get it?”

“What was?”

He sighs.

Years later, I have a longing for truth. If only, for a moment, I’d thought to step off the roller coaster. As irony would have it, it is far too late in the story for that sort of transience. Instead, I’m left with the worn out stories I've reimagined too many times. What would the first layer of the palimpsest look like, before time and fantasy pressed out the creases? There are the things I definitely remember. These are usually brought on by something sensual, and I’m transported through a perception time-warp. Late for work, eating eggs over the frying pan in my kitchen, I recall the morning we went out for breakfast at 2 p.m. after staying up all night. I wanted to leap across the table and push my face hard into his, consume him. Instead, I piled both my eggs onto a piece of toast and shoved them into my mouth. I can still call to mind the feeling of the yolks breaking open in my mouth. Memory is like that – it conceals with a great nonchalance until suddenly, standing over a hot skillet, you are struck with deep loss.

Then, there are things that I think I remember, like the way his wallet fit in his back pocket, or the sheen of sweat across his brow that gave him a look of aliveness. I sort of remember how I used to try and walk on the lower side of the sidewalk so that he would be slightly taller than me. Did Pete actually like Mark Lanegan, or am I confused because it is on a playlist I titled “Thinking of Pete.” I think I remember that we had a beautiful thing, whatever it was, before it went cold and I was alone again.

Finally, there are things that I can’t remember at all. Squeezing my eyes closed, I try to picture him. Colors swirl and expand on the backs of my lids, muddling the outline. I can’t stretch out a face shape, or the perfect fine hairs that caught the sun as they turned. When we lose someone we lose the color of their lips, the way lashes curl around bright curious eyes. I feel my memories jumbling, thickening, my mind sagging with the effort, growing old by the second. I look down at my hands as I ride the subway. They curl in my lap like empty flower pots. I think about how they once held his broad shoulders, felt the blood pump in his temples as I drew him closer.

When we tell stories, do we agree to trade fictions that both of us know – with a strategically suspended knowledge – to be fictions; and is that enough? If histories are built on distortions and lapses, accounts of the past that we pack away without the messiness, are we destined to step into the same river twice? The great irony, of course, that in this sea of fictions there is only one ending we can rely on: death. It is the only thing in this world that is objectively true.

Leah Buckley is a contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in New York.

Photographs by Thomas Bollier.

photo by thomas bollier

photo by thomas bollier

NEW YORK

NEW YORK  Friday, March 2, 2018 at 2:01AM

Friday, March 2, 2018 at 2:01AM