POETRY

POETRY In Which We Become A Quick Kid In A Caper

Thursday, February 1, 2018 at 11:00AM

Thursday, February 1, 2018 at 11:00AM

Nothing At All Certain

The letters of Elizabeth Bishop to Marianne Moore at first reflected a close kinship. The two were always placed in the same sentence despite the vast differences between their oeuvres. Bishop and Moore both eventually chafed at this rotten incorporation, and something of that must have filtered into their relationship. Over time, they found themselves less in unanimity than before. When Bishop moved to South America, she encouraged her friend to come visit her — not this summer, but next.

Bishop's letters, whether to Moore or her friend Robert Lowell, were always excessively detailed. Reading them in full they seem a cataloguing of her various thoughts and feelings, usually ones she could not fully come to terms with until she wrote them down. Miraculous moments occur when you least expect them, and the collection of Bishop vignettes that follows includes excerpts from letters to Marianne Moore, Robert Lowell as well as her friend the lesbian poet May Swenson.

I am so sorry we were late last evening — sorry both to have interrupted you and to have missed that much of your talk. We thought we had timed the subway carefully, but I'm afraid we hadn't. You looked so nice down there on the platform: the black velvet is overwhelmingly becoming, and you should not have apologized for the shoes — they looked extremely, small, shiny and elegant, to me. I enjoyed everything you said and blamed the IRT to being so slow and the audience for not laughing more — as I thought they should have — at your many excellent jokes. And were really quite baffled with admiration when you had to make those impromptu answers.

I enjoyed every moment except the one in which my own name struck me like a bullet, and I felt myself swelling like a balloon to fill the auditorium.

Dr. Williams is even nicer than I had imagined.

+

The page of reports of my useless, unclean and bad-tempered pet delighted my heart. She had never had a bed before. I have always found that starvation was the best method of inducing her to drink milk. And I know she has a deplorable tendency to eat string - also lick glue from envelopes, etc. Perhaps I should have written to you immediately to reassure you about the constipation — but I noticed that always seems to happen when she is taken from one place to another and rights itself — which is so much worse — in a day or two. I have been haunted by so many of my past unpleasant scenes with her.

+

In Cuba & Mexico they have special two-pronged forks for mangos, but you can use a kitchen fork. You stick it in the stem end & if you do it right the fork will go in the soft end of the seed & hold the mango firm. Then you peel it down from the top and eat it off the fork like a lollipop, being very careful not to get the juice on your clothes because it stains badly.

You speak of being "handicapped by solitude", but to me you seem the very height of society. It is terribly lonely here & I feel myself growing stupider & stupider & more like a hermit every day. I'm going to try to stay in New York all winter.

I wish you could have seen the beautiful sight I saw from the bus going to Miami — nine tall white herons in a group, each on one leg, standing in shallow water where mangroves are just beginning to spring up — just an arch here & there with a few leaves on it. The bus was stopped for almost ten minutes — only one moved all that time, took one slow step & looked from the bus down into the water.

This is too long, but I want to talk.

+

Maybe I've felt a little too much the way women did at certain more hysterical moments — people who haven't experienced absolute loneliness for long stretches of time can never sympathize with it at all.

I really feel that you should struggle against your feeling about children...but I suppose it's better than drooling over them like Swinburne. But I've always loved the stories about Shelley going around Oxford peering into baby carriages, and how he once said to a woman carrying a baby, "Madame, can your baby tell us anything of pre-existence?"

+

The missionary is dictating a letter to his wife at the next table. They are so sad, and the worst aspect of the trip has been the two Sundays we've spent at sea on which he held a "small interdenominational service." There are so few of us we all had to attend and sing "Nearer My God To Thee" (after he told the story of how the people on Titanic sang it as they went down). The three tiny boys sang "Jesus loves me this I know" in Spanish, and a song, with gestures, about how the house built on the sand went splash. I'd always wondered how it did go, but I had never thought of it as splash somehow.

+

I am puzzled by what you mean by my poems not appealing to the emotions. (I'm sorry to be so full of myself but your letter has brought it on.) What poetry does, or doesn't? And doesn't it always, in one way or another? A poem like "Never until the mankind making" etc. one feels immediately, before one starts to think. A poem like "The Frigate Pelican", one thinks before one starts to feel. But the sequence, and the amount of either depends as much on the reader as the poem, I think. And poetry is a way of thinking with one's feelings, anyways. But maybe that's not what you mean by "emotion." I think myself that my best poems seem rather distant, and sometimes I wish I could be as objective about everything else as I seem to be in and about them. I don't think I'm very successful when I get personal — rather, sound personal — one always is, of course, one way or another.

+

I bought Pablo Neruda's poetry (he & his wife have been very nice to us) & am reading it, with the dictionary, but I'm afraid it is not the kind I — nor you — like — very, very loose, surrealist imagery etc. I may be misjudging it; it is so hard to tell about foreign poetry, but I feel I recognize the type only too well. His chief interest in life (or did I tell you about all this) besides communism seems to be shells, & he has a beautiful collection most of them laid in the top of a sort of large, heavy, specially built coffee-table, with glass over them.

+

Sammy, the toucan, is fine — a neighbor built him a very large cage in which he seems quite happy, and I give him baths with the garden hose. Someone also brought him a big pair of gold earring from the Petropolis "Lojas Americana" (5 & 10) and he loves them. He has two noises - one a sort of low rattle in his throat, quite gentle, if he is pleased with you, or cranky, if he isn't, and the other, I'm afraid, a shriek. He also has the shortest intestinal tract ever known I think, and has to eat constantly, and is far from neat.

Just a few minutes ago I found a hummingbird in the pantry — quite a big one, yellow and black. I got it out with an umbrella. There are such varieties of them — and now the butterflies have come for summer - some enormous, pale blue iridescent ones, in pairs. I gave Loren one in a box once — maybe you've seen it at her house. And I've never seen such moths — I wish I had my equipment with me & I'm going to try to get some in Rio. The house is all unfinished and we're using oil lamps so of course we get thousands and mice, and large black crabs like patent leather, and the biggest walking-stick bugs I've ever seen — well it is all wonderful to me and my ideas of "travel" recede pleasantly every day.

+

The first time I met Dylan Thomas, when he spent a day with me doing these recordings in Washington, he and Joe Frank and I had lunch together, and even after knowing him for three or four hours I felt frightened for him and depressed and yet I found him so tremendously sympathetic at the same time. I said to Joe later something trite about "why he'll kill himself if he goes on like this" etc, etc — and Joe said promptly, "Don't be silly. Can't you see a man like that doesn't want to live? I give him another two or three years..." And I suppose everyone felt that way, but I don't know enough about him really to understand why. Why do some poets manage to get by and live to be malicious old bores like Frost or — probably — pompous old ones, like Yeats, or crazy old ones like Pound — and some just don't?

+

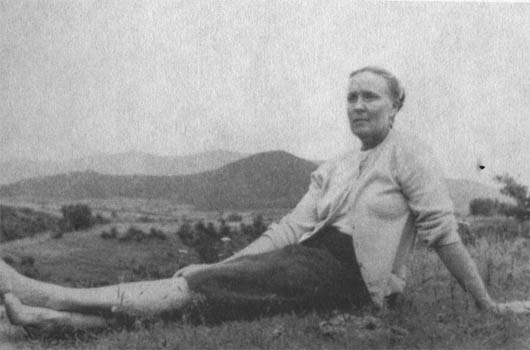

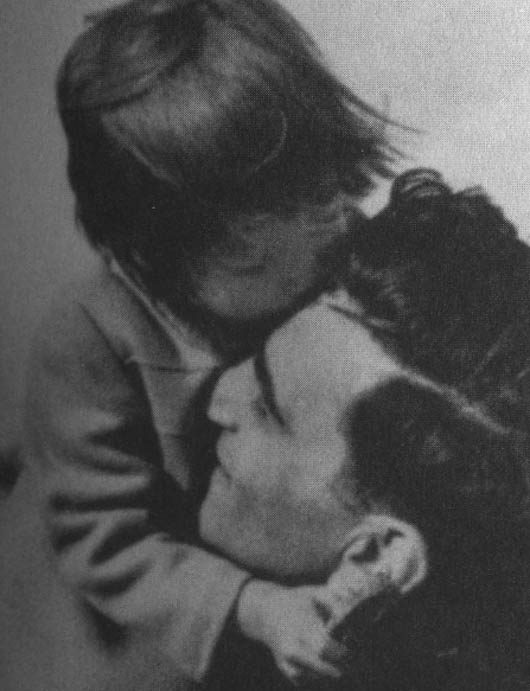

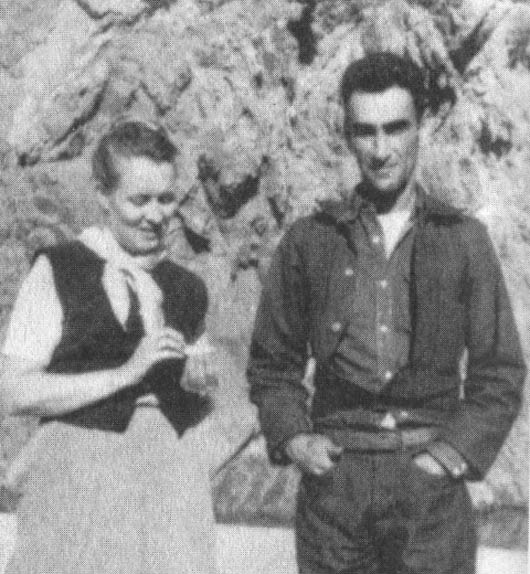

Elizabeth Bishop met Lota de Macedo Soares in Mexico in 1942. Lota was traveling with her girlfriend at the time, the American dancer Mary Stearns Morse. When she visited Lota in Brazil, she fell victim to a violent allergic reaction to cashews. Nursing Bishop back to health in 1951 led to the two falling in love and spending the next 15 years together. A talented architect, Lota built a studio for Bishop on her property in Rio.

In the late sixties, Lota suffered a nervous breakdown brought on in part by political circumstances in Brazil. Eventually, Bishop couldn't take it anymore and returned to New York. Lota followed her there in 1967 after a year of threatening suicide. Upon her arrival in New York, she took an overdose of valium and went into a coma before passing away. The following excerpts from Bishop's letters to Robert Lowell as well as her therapist and various amateur biographers detail the years following Lota's suicide.

I'm afraid you thought I was drunk when I called you, but I really wasn't — just closer to hysteria, or more hysterical, than I have ever been in my life, and although I realized there wasn't much you could do or say all those thousands of miles away it helped some just to hear you. I am afraid by now you are pretty bored with me and my neurotic friends, etc. — but I thought you liked and admired Lota when you were here and I sort of wanted you to know, maybe, that I wasn't entirely wrong in my complaints from Seattle. I felt at the time that you thought I was being loyal and unsympathetic about her work, etc. — but as you can surely see now, it is all much worse than I thought, even.

I suppose the person closest is the last to realize how terribly sick someone is — but things have been getting worse and worse for several years now.

I only wish to God I knew if they are doing the right thing. Her nurse comes here to see me once in a while and yesterday said she is staying awake more now, and eating more — but talks of me constantly, etc.

She has had violent fights with all our friends except two — and it seems they all thought she was "mad" severally years before I did. But of course I got it all the time and almost all the night, poor dear. I do know my own faults, you know. But this is really not because of me, although now all her obsessions have fixed on me — 1st love, then hate, etc. I finally refused to stay alone with her nights any longer — she threatened to throw herself off the terrace.

I have almost decided to try the U.S. thing. I don't know what is right really, and wish God would lean down and tell me. I hate to leave Lota like this, but it seems almost as if it were a question of saving my own life or sanity, too, now.

+

Have you ever gone through caves? I did once, in Mexico, and hated it so I've never gone through the famous ones right near here. Finally, after hours stumbling along, one sees daylight ahead — faint blue glimmer — and it never looked so wonderful before. That's what I feel as thought I were waiting for now — just the faintest glimmer that I'm going to get out of this, somehow, alive.

+

One phrase I can't abide — it may be what everyone says at present, but it always offends me — is "to have sex." (Even Isherwood has used it.) If it isn't "making love" — what other way can it be put? (I first heard about it years ago when the famous fan dancers was talking about her pet snake — maybe that prejudiced me.) It seems like such an ugly, generalized sort of expression for something — love, lust, or what have you — always unique, and so much more complex than "having sex."

+

I've never studied "Imagism" or "Transcendentalism" or any isms consciously. I just read all the poetry that came my way, old and new. At 15 I loved Whitman; at 16 someone gave me the book of Hopkins that had just been re-issued. I never really liked Emily Dickinson much, except a few nature poems, until that complete edition came out a few years ago and I read it all more carefully. I still hate the oh-the-pain-of-it-all poems, but I admire many others, and mostly, phrases more than whole poems. I particularly admire her having dared to do it, all alone — a bit like Hopkins in that. (I have a poem about them comparing them two self-caged birds, but it's unfinished.) This is snobbery — but I don't like the humorless, Martha-Graham kind of person who does like Emily Dickinson.

In fact I think snobbery governs a great deal of my taste. I have been very lucky in having had, most of my life, some witty friends, and I mean real wit, quickness, wild fancies, remarks that make one cry with laughing. (I seem to notice a tendency in literary people at present to think that any unkind or heavily ironical criticism is "wit," and any old "ambiguity" is now considered "wit," too, but that's not what I mean.) The aunt I liked best was a very funny woman: most of my close friends have been funny people; Lota de Macedo Soares is funny. Pauline Hemingway a good friend until her death in 1951 was the wittiest person, man or woman, that I've ever known. Marianne was very funny — Cummings, too, of course.

Perhaps I need some people to cheer me up. They are usually stoical, unsentimental, and physically courageous.

I have a vague theory that one learns most — I have learned most - from having someone suddenly make fun of something one has taken seriously up until then. I mean about life, the world, and so on. This is again a form of snobbery. I dislike extremely bookish people (I do happen to love some, but I think they'd be better off if they weren't so bookish), and I don't enjoy writers who talk literary anecdotes all the time or are preoccupied in putting other writers in the proper pecking order. Criticism is important, "weeding out has to be done," (R. Lowell), but I don't want to do it. I feel that art would probably struggle along without it in very much the same way, probably. I trust my own taste and usually don't want to explain it — at the same time I occasionally wish I could explain it better.

+

I had meant to remark that I have been seeing some poems around by an Anne Sexton that reminded me quite a bit of you and also were quite good, at least some of them — and the same day your last letter came Houghton Mifflin sent me her book, with your blurb on the jacket and that sad photograph of her on the other side of it. She is good, in spots, but there is all the difference in the world, I'm afraid, between her kind of simplicity and that of Life Studies, her kind of egocentricity that is simply that, and yours that has been —what would be the reverse of sublimated I wonder — anyway, made intensely interesting, and painfully applicable to every reader. I feel I know too much about her, whereas, although I know much more about you, I'd like to know a great deal more, etc, — oh well it is fairly obvious, isn't it?

I like some of her really mad ones best; those that sound as thought she'd written them all at once.

+

I liked Roethke when I saw him — huge people like that often have that lightning quickness. I went to Grand Central with him in cab; he was almost missing his train to the west and I suggested my doing something while he did something else — I forget what, but to help him catch the train, and his last words to me were, "You're a quick kid in a caper."

+

The biographical note in Who's Who is correct — or was, the last time I saw it. I never lived in Worcester, however — I left before I was a year old and spent only a few months there was I was 6-7, with my father's parents. The rest of my childhood I spent with my mother's parents in Nova Scotia - mostly long summers, although I started school there — and with a devoted aunt, in or near Boston, until I went away to school at 16. I also went to summer camp on Cape Cod for 6 summers. I've never lived in Newfoundland — I took a walking trip there one summer when I was at Vassar. Since Vassar I've lived in New York, Paris, Key West, Mexico, etc — mostly New York, and Key West until about 1948. Then since late 1951 Brazil — with several trips back, of course, one of 8 months or so.

Robert Lowell compressed my life even more, recently, into a very short poem that was in the Kenyon Review, called "The Scream."

THE SCREAM

A scream, the echo of a scream,

now only a thinning echo . . .

As a child in Nova Scotia,

I used to watch the sky,

Swiss sky, too blue, too dark.

A cow drooled green grass strings.

made cow flop, smack, smack, smack!

and tried to brush off its flies

on a lilac bush—all,

forever, at one fell swoop!

In the blacksmith’s shop, the horseshoes sailed through the dark,

like bloody little moons,

red-hot, hissing, protesting,

as they drowned in the pan.

Back and away and back!

Mother kept coming and going—

with me, without me!

Mother’s dresses were black

or white, or black-and-white.

One day she changed to purple,

and left her mourning. At the fitting,

the dressmaker crawled on the floor,

eating pins, like Nebuchadnezzar

on his knees eating grass.

Drummers sometimes came

selling gilded red

and green books, unlovely books!

The people in the pictures

wore clothes like the purple dress.

Later, she gave the scream,

not even loud at first . . .

when she went away I thought

“But you don’t have to love

everyone,

your heart won’t let you!”

A scream! But they are all gone,

those aunts and aunts, a grandfather,

a grandmother, my mother—

even her scream—too frail

for us to hear their voices long.

+

The trouble is — excuse my clichés — as people grow older, non-artists, that is, they do have to steel themselves so much, forget so much and try to pretend everything's all right so much. They are afraid, probably rightly, that poetry — any art — if they take it hard, might upset them — so they pretend they like it at the same time they resist it absolutely — Nao e?

I'm feeling so much better these days.

1936-1970