ART

ART In Which We Bargain With A Frightened Man

Friday, January 26, 2018 at 5:49AM

Friday, January 26, 2018 at 5:49AM

Painting of a Thousand Faces

by MARK ARTURO

We are angry. We are angry with you for what you did.

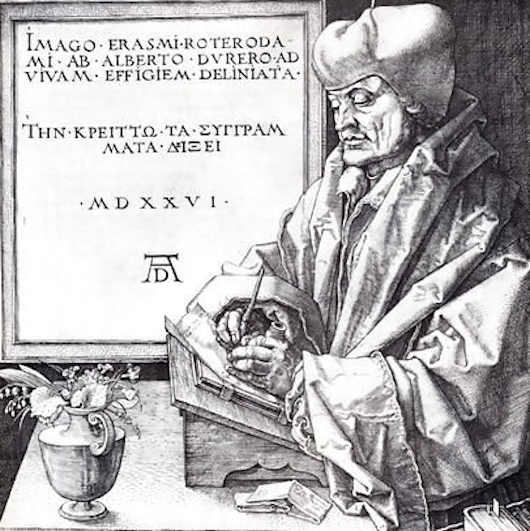

You further reproach me with having promised you that I would paint your picture with the greatest possible care that I ever could, Dürer wrote. That I certainly said unless I was out of my mind. For my whole lifetime I could hardly finish it. Now with the greatest care I can hardly finish a face in half a year. Now your picture contains fully one hundred faces, not counting the drapery and landscape and other things in it. Besides who ever heard of making such a work for an altarpiece? No one could see it. But I believe that what I wrote to was: to make the painting with great or more than ordinary pains because of the time you spent waiting for me.

We imagine modernity began with the last man to speak, the last man that we recognize. (Or woman.) Did you know that the ancient Egyptians had indoor plumbing? Civilizations are circular, cyclical, and we return to the end of the line.

The central posited fact, that remains through the ages, is an image in my mind. A man sits on the edge of a sunset and bakes himself into a landscape. Perhaps he would rather be with a man or a woman but he is unmoving in the firelight. I want you to know for all my days I have never begun any work that pleased me better than this picture of your which I am painting. Till I finish it I will not to any other work, Albrecht Dürer wrote. I am only sorry that the winter will so soon come upon us. The days grow so short that one cannot do much.

Life at the turn of the sixteenth century was all double entendres and unprotected sex. Man considered visiting the moon before deciding he had other things on his mind. 1503 was the kind of year where you wondered why there had been any other. Dürer had three journeymen on his payroll; all were named Hans. Dürer was the type of guy where a part of him was in the present and a part was in the past.

He felt he had missed out on books of art written by close friends. "Phidias, Praxiteles, Abelles, Polteclus, Parchasias, Lisipus, Protogines." He wondered what they wrote about the thing he loved. There were times in history where mankind thought art was a pejorative, a casting of evil. Maximilian asked Dürer for a design of a knight; it would adorn his tomb at Innsbruck.

Sometimes it seems odd how little Christ is talked about by nonbelievers as a historical figure. He is a character as much as Dürer, although he was not as light in the face as Dürer, and he did not smell of turpentine, bleach, and painting oils. When a man understands the thought of another, he can only understand it on as many levels as he can comprehend at one time. Some, like Dürer, could simply hold many more thoughts. The expression of the additional levels was present, here for example:

We are eight to a side, we are sitting at the table until we fold beneath it, our wings pressed down, facing the ground.

Erasmus writes of Jesus Christ that, He despised the eating of his own flesh and drinking of his own blood, except it were done spiritually. This is an analog for history. The history of our people is different somehow, because there is no longer such thing as flesh and blood.

Dürer's mother gave birth to eighteen children. Her name was Barbara. Dürer wrote, God be merciful to her. On her deathbed he drew her. We had the chance to make peace at the end, but we only stayed away. Mankind, in its infinite wisdom killed something precious, and the only way to move on emotionally was to kill something else precious. A few years later, Dürer began to lose his eyesight. He left Nuremberg for a time, determined to see other surroundings.

Mark Arturo is the senior contributor to This Recording.

albrecht durer,

albrecht durer,  erasmus,

erasmus,  mark arturo

mark arturo