TV

TV In Which The Show Concerns A Deceitful Bench

Tuesday, April 10, 2012 at 1:00PM

Tuesday, April 10, 2012 at 1:00PM

You Can’t Say Th-- on Television

by ALICE BOLIN

Don't Trust the B---- In Apt 23

creator Nahnatchka Khan

Highlights in American history: 1989, the year when Seinfeld freed the situation comedy from the tyranny of the situation. Never forget. No one was about to.

Situation of the new situation comedy Don’t Trust the B---- in Apartment 23: an ambitious MBA grad (Dreama Walker) moves to Manhattan for a job on Wall Street. On her first day of work, the feds shut down her company, and she is forced to find a roommate and a job at a coffee shop. Her roommate (Krysten Ritter) is a con artist who intends to take her money and make her life hell, driving her out of the apartment. Over the course of the pilot, con artist drops her scheme and exposes MBA grad’s boyfriend as a cheating dirtbag. Con artist is also BFF with former Dawson’s Creek actor James Van Der Beek.

Oh, so it’s just about a group of friends who live in New York City?

Yeah, pretty much.

Television is a single gargantuan organism, and with each teen supernatural soap opera, each humiliation-porn game show, each mid-season replacement wacky roommates sitcom, it grows a new appendage. This intertextuality is why there is nothing new on television, and there never will be; why we have to name Murphy Brown as the second coming of Mary Tyler Moore. It is endless entertainment industry samsara, where shows are reincarnated again and again. St. Elsewhere begets ER begets Grey’s Anatomy. I watch Mad Men and I think, I liked this better when it was called Bewitched.

But it’s not only the influences and clichés, it’s the trends. Just think of the weird Hollywood mega-mind that brought forth 30 Rock and Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip at the same time, that produced waves of blended family shows, shows about orphans, shows starring Bob Newhart, that gave Whitney Cummings two shows in one season. And the actors are always a problem. A guy who murdered his wife on one episode of Law and Order plays a defense attorney on another episode and they don’t expect that to cause some mental dissonance? Am I supposed to see Mark-Paul Gosselaar on another show and not think of him as Zack Morris?

Confronting these obstacles to originality, some shows decide to go limp in the face of cliché, to submit to television’s connectedness. This is the tack Don't Trust the B---- in Apartment 23 takes to save itself from mediocrity. June, the MBA grad, says at the beginning of the pilot that she thinks her life in New York will be just like Friends. The show clearly knows its lineage, and throws itself into its situation comedy antics full force. Chloe, the con artist played by Krysten Ritter, is hyperbolically amoral and debaucherous, gargling in the morning with peppermint schnapps (“a whore’s toothbrush”) and hiding contraband Chinese energy tablets in her grandma’s antique ottoman — her hijinks are all the more cartoonish because Ritter looks like a beautiful baby giraffe. There is the sitcom-staple weird neighbor, Eli, who we only ever see through an open window. Wikipedia refers to him as “quirky,” though his schtick is actually “always masturbating.”

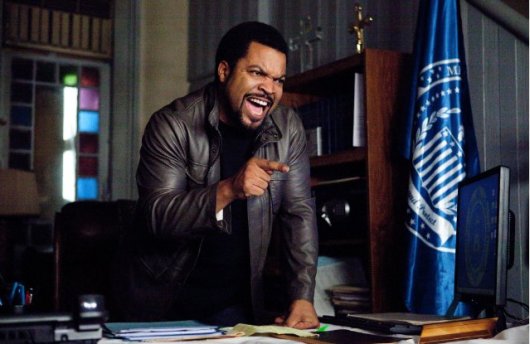

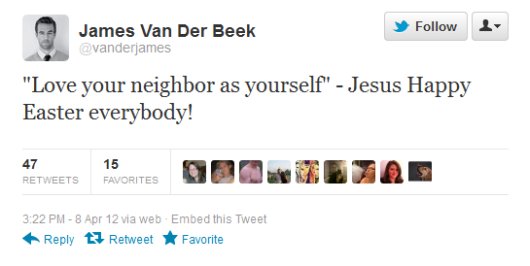

Van Der Beek is the most overtly self-conscious part of Don't Trust the B---- in Apartment 23 — he complains on the show that people only ever think of him as Dawson Leery, his role on the classic ‘90s teen soap opera Dawson’s Creek, and won’t give him a chance to play other roles. “I was in an all-white version of Raisin in the Sun!” he says, asserting his acting chops. When he teaches an acting class at NYU, in an attempt both to compete with and emulate James Franco, all he writes on the chalk board is “JAMES VAN DER BEEK!!!” and circles it three times. Van Der Beek has a good sense of humor about himself, as the fictional James Van Der Beek is shown as a frivolous playboy, seducing women by playing the theme song to Dawson’s Creek and wearing Dawson’s trademark flannel.

This is absurd, of course — he couldn’t even lure Dawson’s Creek super fans this way. Van Der Beek’s Dawson’s Creek character was a whiny fifteen-year old wannabe filmmaker with a massive, doughy face who struck out with both bad girl Jen, played by Michelle Williams, and tomboy Joey, played by Katie Holmes. The true heartthrob of the show was Joshua Jackson’s Pacey Witter, who began the series with a storyline about fucking his hot English teacher. Williams’ Academy Award nominations and Holmes’s movie career and high-profile weirdo celebrity marriage would also indicate that there is no Creek curse — it has pretty much only been bad for Van Der Beek. But Dawson was remarkable for his skewed self-perception, always viewing himself as a nice guy who finished last rather than a babyish beta male, so maybe Van Der Beek’s I-was-a-huge-1990s-crush-object schtick on Don't Trust the B---- in Apartment 23 is just following in Dawson Leery’s deluded tradition.

There is a myth that self-consciousness is critique. A lot of low culture is marked by the use of formulas— television, pop music, genre fiction. Parody uses the formula to comment on the form; self-consciousness only points out that the formula exists, and continues to use it. When both the creator and the consumer can say, “I know I’m not supposed to like this, but I do,” everyone feels better about themselves. Similarly, any fondness for somewhat stupid cultural relics of the recent past, Dawson’s Creek, for example, is protected by nostalgia. These forms of passive self-awareness are designed to allow me to like Katy Perry or Gossip Girl or Twilight while still thinking of myself as too smart to like those things. Self-consciousness is a guaranteed way to transcend the trash while still participating in it.

It’s a natural impulse to not want to be one of those fans — the ones who post pictures of Krysten Ritter on Tumblr with lines from Sylvia Plath about dying being easy and tag it #Anna Karenina and #Leo Tolstoy. We apply some remove to save ourselves from the embarrassing adolescent earnestness. Don’t Trust the B---- in Apartment 23 is also just applying remove, rather than contributing any innovations to the situation comedy form. But I think of the alternative, the dozens of crappy traditional sitcoms that are still on the air, recycling jokes about in-laws and women wanting to cuddle after sex and airplane food and white guys drive like this, black guys drive like this, and I wish for one second they could acknowledge how stupid they were. Self-consciousness isn’t inherently virtuous, but TV can always use a new gimmick.

Alice Bolin is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Missoula. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She last wrote in these pages about nostalgia. She tumbls here and twitters here.

"You Don't Make It Easy Babe (live on Vicar Street)" - Josh Ritter (mp3)

"You Don't Make It Easy Babe (acoustic)" - Josh Ritter (mp3)

alice bolin,

alice bolin,  krysten ritter

krysten ritter