THE FUTURE

THE FUTURE In Which We Profit Entirely By Conjecture

Friday, October 25, 2013 at 10:19AM

Friday, October 25, 2013 at 10:19AM

Wormholes

by CATHALEEN CHEN

I believe in quantum physics, kind of. I don’t study it and I certainly can’t prove it, but like Christians in a casino or a child in a buffet line, I muse its most attractive theories.

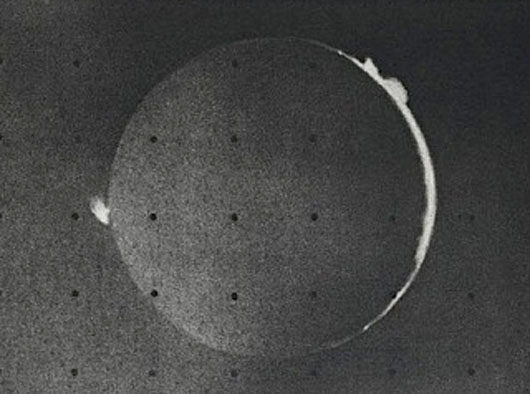

Wormholes, for instance, are tunnels of negative space energy that link sets of any two points in the universe. The conjecture of Stephen Hawking and a handful of science fiction writers, wormholes can be visualized as a funnel between a two-dimensional surface that folds over a third dimension, allowing the two ends of the funnel to be however infinitely apart, yet connected. Black holes, the nihilist version of wormholes, have funnels with only one end that eventually tapers into nothingness.

Admittedly, I had to Google “wormhole” for its technical definition. I used to snooze through physics class except for when my teacher, a young, lanky Christian, born and raised in western Pennsylvania, would use words like “spacetime” and “exotic matter” to describe phenomena that he attributed to God.

Maybe it was Mr. Gardner’s sermon-like cadence or maybe I so desperately want to grasp onto some sort of cosmic enlightenment, but the notion of wormholes and dark matter stuck with me. At first they were just nice ideas to cogitate, theories with which to coyly embellish a conversation and to speak of with a tinge of irony. But certain things in life have a way of popping up and then disappearing, and as I encounter more and more strange, arbitrary happenings, I’m now willing to accept the mysteries of life as mysteries of the cosmos.

by vija celmins

by vija celmins

Now consider this: I am a 20-year-old Chinese immigrant, a soon-to-be first generation American citizen and the daughter of a scientist. Having spent the first eight years of my life in Communist China — i.e., modern China — I didn’t have a conventional childhood.

In the first grade, my classmates and I were indoctrinated as junior comrades of the Party. We were sanctioned to wear red ribbons around our necks, which I thought at the time was to commemorate Mao Zedong’s favorite color. In the second grade, I participated in a school-wide campaign against superstition and religion. The principal recited Marx over the intercom.

In the third grade, I found myself scrutinized by inquisitive faces, some with yellow hair and blue eyes, like the Chinese imitation Barbies I used to own. This was in Morgantown, West Virginia, where I spent my next five years learning about the English language, Harry Potter, chicken nuggets, the Beatles and eventually, about god.

I guess God could’ve been an easy fix for the perpetual cultural quandaries that ensued in my adolescence. If Chinese counterfeit Barbies had yellow hair and blue eyes, why didn’t I? And how could I have let my parents eat spaghetti with chopsticks in front of my friends?

by vija celmins

by vija celmins

But I was the daughter of a scientist, a communist expatriate scientist for that matter. I was never sold on god. I had science and Marx, and I’d rather not elucidate upon the latter, though it’s probably in my blood.

Out of my white, baptized group of friends, I think I was the first to board the bandwagon of existential doubt (I was later reaffirmed by my uncanny keenness for A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). They’ve caught on by now, of course. We are twenty-somethings, after all. But all of this — the communists, the angst, the James Joyce — leads me back to the notion of wormholes, black holes and dark matter.

Let’s, for a moment, forget about the grandiosity of existence. Forget about life and death and the meaning of it all. Let’s look at the little luxury of poetry and of language, a practical and tangible thing. For all intents and purposes, let’s consider it matter, because it exists in ink on paper and thus, it exists in some sort of fathomable sphere. Different languages, then, are the different states of matter and each meaning is like an element on the periodic table — it can differ in form but never in essence.

But that’s not how language works. Human communication does not follow the conservation of mass and energy. Take the Chinese word, 亲人, or “tsing ren.” The most direct translation in English would be “relative” or “kin.” But that’s far off from the literal meaning of the Chinese word, which in essence, means someone who is close to the heart. The essence of the word, therefore, disappears through translation — the same way matter disappears into the singularity of a black hole.

Likewise, emotions can be contextualized as matter or energy. Anger, apathy and happiness — among the infinite palette of human emotions — can be traced to a specific part of the insular cortex, i.e. the left side of the brain, induced by a specific sequence of nerves and receptors. Feelings, at the very least, are energies we utilize. But when a certain mental sensation is channeled into something else — say, a jog around the neighborhood, an act of revenge, a personal essay — its existence transcends the human body and recalibrates on another medium, separate yet connected to its origin in the mind.

by vija celmins

by vija celmins

On the other hand, emotional energy without an outlet eventually dissipates and ceases to exist entirely. In certain cases, caffeine might be a good remedy. But some, if not most, feelings fade, and nothing can change that. Not even caffeine can make love forever. Shakespeare knew that, though I didn’t believe him until I was 16 and on the receiving end of lost affections, adrift in the relentless gravitational pull of a black hole. I was the end of the funnel.

When we lose something in life, we’re told to let go. In order to grieve, we must eventually accept the dearth of a being that used to be. We quote Vonnegut and buy posters that say “live and let love” to hang on bare walls. We put up and put out. It goes against the circle of life, in which everything is supposed to be connected. And then at some point down the road, we must accept that Mufasa was wrong and that not everything exists in the paradigm of a beginning, middle and an end that leads to new beginnings.

It seems to me that the universe is full of contractions — of conservative Christian physics teachers, of irreconcilable languages and of parents who eat Italian pasta with chopsticks. I hear the universe is also constantly expanding, perpetually mobile, like a haphazard middle school dance with which the only way to keep up is to accept the fact that it’s supposed to be awkward and random and at times, tender. This, I believe.

A few months ago, I was reading 1984 on my commute to work. It was a typical rush hour El ride until I noticed that the lady standing over me was also reading 1984. It would’ve been a regular, serendipitous coincidence if it weren’t for the fact that she was holding the very same Signet Classic paperback edition, published 1950. Mine was a literary artifact that I borrowed from my roommate, who received it as a birthday present from his sister in 2004. To put this in context, there are more than 450 English editions of Orwell’s masterpiece, nearly 800,000 El passengers each weekday and approximately 145 different El stops in Chicago. I’m not really sure what it meant or if it means anything at all. But in that moment, I was reminded of a particular day in AP Physics. I had woken up just in time before the class was dismissed to see Mr. Gardner drawing a worm poking out of a black circle on the white board.

“There are things in physics I can’t really explain,” he said, dotting two little eyes on the worm. And then the bell rang.

Cathaleen Chen is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Chicago. You can find her twitter here. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She last wrote in these pages about Chopin.

"The Old and the Young" - Midlake (mp3)

"This Weight" - Midlake (mp3)