THE PAST

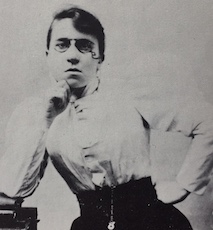

THE PAST In Which Emma Goldman Served Her Time In Missouri

Thursday, May 4, 2017 at 10:43AM

Thursday, May 4, 2017 at 10:43AM This is the second in a two part series. You can read the first part here.

Emma, Incarcerated

by ELLEN COPPERFIELD

Time meant nothing. The world was immediate, without past or future. Every tree and bristly bush attained a sharp, stark clarity. Faces loomed, split by immense grins. Crisp light poured through them all, illuminating everything with an even, eternal glow. Each stored increment awaited only a release of control in order to speak its pain. - Gregory Benford

Being arrested was becoming de rigeur for Emma Goldman and her boyfriend Dr. Ben Reitman. As her interests turned to the rights of women, passing out birth control and information about it regulary led to both members of the anarchist couple being forced to spend time in jail or a workhouse. Later, Reitman served six months in prison for distributing illegal pamphlets in Cleveland.

Emma Goldman's penalties for the same crime were usually not quite so severe, and sometimes her convictions were overturned in New York courts. Given the choice between prison and a fine, she always selected the former out of principle.

But prison changed Emma Goldman no matter how long she was inside. "I don't know whether you will understand the feeling since you have never had the experience," she wrote, "but I felt more miserable yesterday and today than on the day I was sentenced and in fact the two weeks while I was in prison. However there is no time to contemplate one's feelings." Once Reitman had served his time, he begged Emma more forcefully than ever to marry him and settle in one place.

She declined the nuptials, but at the end of 1913, Emma Goldman purchased a Harlem brownstone on 119th Street. With four floors and a tremendous open feeling, this house was quite spacious. Ben suggested his mother move in with them, and Emma tentatively agreed. She may have intimated the disastrous effect having Ben's mother on the premises would have on her sex life and overall well-being.

Instead of being one happy home, the experience of living together was nothing short of a disaster. Emma's ex-boyfriends and fellow travelers used the house as their own, and Reitman grew resentful of being financially dependent on Goldman. "I am 35 years old, and I haven't a thing," he told her, "and I am only the jester, joker or clown. I don't amount to a damn in the movement and I know it." Reitman and his mother bailed and moved back to Chicago.

Ben suggested they live in a small apartment of their own, but Emma had grown tired of the domestic experiment. The house consumed most of Emma's income from lectures, and hangers-on ate any food on the premises. She moved into more spare quarters on E.125th. "I am so tired of lectures, meetings and the mad chase," she told Reitman. She asked him to go on the road with her again, and he hesitantly agreed. During that trip Reitman met Anna Martindale, an English expat who was crusading for a woman's right to vote. He began seeing Anna when Emma was at meetings or in other towns.

In 1917, Ben Reitman married Anna Martindale. Emma was distressed, but a part of her knew this was inevitable. She turned to her work, where she found that she missed her manager as much as her sexual and emotional partner. Protesting the first World War was her focus. Police arrested anyone at her lectures who could not produce a draft card. Eventually, they arrested Emma in her home. She prepared for trial at the age of 48. The charges were outlandish, but the political climate was completely against her. Goldman was accused of accepting German money, of inciting violence, and preventing draft registration. A jury aided by a deeply biased judge found her guilty and Emma was sentenced to the maximum: two years. The New York Times enthusiastically praised the verdict.

Emma avoided jail on appeal for the moment and helped her friends, many of whom were also pursued by the law. Ben Reitman served his time in a workhouse; others were deported. The post office refused to mail any of her newsletters, and she was forced to shut her magazine (Mother Earth). Emma finally thought of leaving her adopted country. She knew that it was unlikely she would be allowed back if she left for Russia, and this scared her.

Before she could flee of her own volition, the Supreme Court rejected her appeal and she was sent to federal prison in Jefferson City, Missouri. "In moments of depression I look to Russia," she wrote in a letter. "She acts like a ray of sunshine working its way through black clouds." It was a most half-hearted hope.

Missouri State Penitentiary was the biggest prison in the United States, with a population of 2300 inmates. The cells for the 100 women situated there were 7x8 with a working sink and toilet. Straw was both mattress and pillow. Prisoners spent their days manufacturing clothes in the shop; the smell throughout was pervasive. The dining hall was filled with cockroaches. Breakfast was sugar, bread and coffee. Potatoes were inedible. Twice a week, the women got oatmeal. Lunch featured beef, dinner incorporated a soup ridden with worms. Talking during meals was not permitted, and overall conditions were wretched.

Most of Goldman's fellows were mentally ill. The library would not have been much use to them anyway, but women were not permitted to have books until the prisoners appealed. Bent over a sewing machine all day, Emma suffered intense pain in her neck and spine. Going outside was only permitted on Sunday, although this brief pleasure was denied Goldman because she would not attend church. The day was still a blessing, since she was allowed to spend all morning reading and writing letters.

Upon her release from prison in 1919, Emma Goldman took a train to Chicago. She had not seen Ben Reitman in years. Traveling with her niece, she met Ben, his wife, and their daughter in that city. After leaving prison, Reitman had opened up a private practice and was researching birth control in free hours. In Rochester Emma saw her mother for the final time. She would be deported to Russia on December 21st, 1919.

Whether she was angry to be forcefully removed from the United States is not evident in her letter to Ben Reitman. "Their mad rush in getting us out of the country is the greatest proof to me that I have served the cause of humanity," she wrote. She continued:

I was glad to have been in Chicago and to see you again, dearest Hobo. I never realized quite so well how far apart we have travelled. But it is alright, nothing you have done since you left me, or will yet do can take away the 10 wonderful years with you. If it is true that the power of endurance is the greatest test of love, Hobo mine, I have loved you much. But I have been rewarded not only in pain - but in real joy - in ecstasy - in all that makes life full & rich & sparkling.

Ellen Copperfield is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in San Francisco. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here.