The 100 Greatest Writers of All Time

by WILL HUBBARD and ALEX CARNEVALE

Other lists of this kind have been attempted, none very successfully. We would like to stress that there is a crucial difference between "an important writer" and "a great writer"; the latter is at this time our sole interest. We will account for some of the names that did not make this list in a later dispatch. There is nothing bad to say about anyone we list here, except in some cases that they were anti-Semitic or racist, hated women or hated men. Literary crimes are usually relative, the caveats of which we shall enumerate:

100. Joseph Conrad

Prose stylist nonpareil, he addressed the dichotomy of race, the loneliness of existence. Heart of Darkness became a paradigmatic work. It is hard to read today, but no less important. Conrad was born to a family of Polish nobles. He did quite a bit of gunrunning — see The Arrow of Gold. You've got to be batshit crazy to have an ambition, as a child, to visit Central Africa. Recommended reading: The Secret Agent.

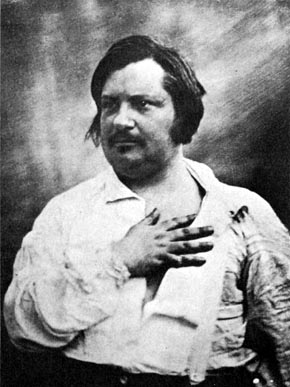

99. Honoré de Balzac

The gestamtkunstwerk ('total work of art') was all the rage in Europe early in the last century, but Balzac was on the case almost a hundred years before. The man started writing just before midnight and worked until the sun went down the next day, eventually producing 100 novels and plays he called La Comedie Humaine. We've never really liked realism, but Le Pere Goriot is one of the mode's best. His mother came from a family of haberdashers. There had to be a realism before there could be anything else, probably. Recommended reading: "The Girl With The Golden Eye", "The Marriage Contract" from La Comedie Humaine.

98. Czeslaw Milosz

The greatest artist Poland would ever spawn, Milosz was still composing vital poetry until his death in 2004. He was constantly reinventing himself as a writer, but remained pretty much the same person after he took home the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980. Born a Lithuanian, he became a U.S. citizen eventually, and dissected the intellectual attraction to communism in his masterpiece The Captive Mind.

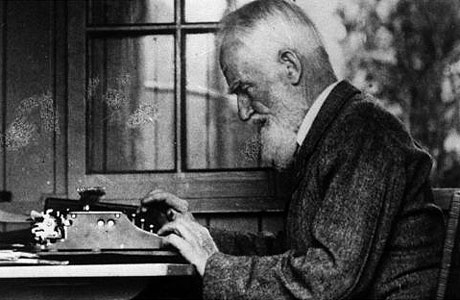

97. George Bernard Shaw

When we speak of 'wit' in the theater we owe a debt to G. B. Shaw. In fact, his scripts are so funny there's hardly any reason to see them performed. Pygmalion's a great play, but his writing after WWI, most notably Heartbreak House, is darker and better.

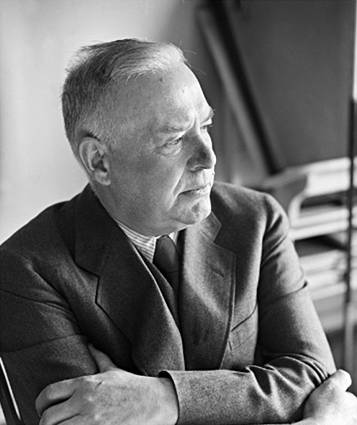

96. Wallace Stevens

Anti-semite? Sure. A little old-fashioned? No doubt. Was he one of the greatest poets of the twentienth century? No question. You might say that Stevens never quite seems like himself, which is a towering accomplishment, because he never quite sounds like anyone else either. Recommended Reading: 'Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,' 'Anecdote of the Jar,' 'Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction'.

95. Rumi

We prefer to keep our religion, poetry, and booze in separate containers, but we know a lot of ex-hippie poets who swear by this guy. The Coleman Barks translations are the gold-standard. Born in modern-day Afghanistan, Rumi might as well have been a god.

94. W.G. Sebald

No writer so little acclaimed in the first part of his life lived a second one in literary style in the West. Sebald can reasonably contend to have invented much of this country's creative nonfiction, and that is simply a glint of his admirers. It is for good reason that he is taught in every graduate writing program in America: his novels of half-remembrance are brilliant interlocking art pieces; seen whole they completely explain the violence in the middle half of the 20th century. Recommended reading: The Rings of Saturn, The Emigrants.

93. Robert Hayden

Hayden's reputation is sure to be burnished by time. Sure, he had influence on an entire generation of African-American poets; but it is the sustained quality of his verses that we now have to contend with. His was an intellect of constant seriousness, mapping the tragedy of his own heart. His vision of language and life, in elegy or eulogy, is among the most impressive achievements in the arts. Recommended reading: "Those Winter Sundays", "October," Selected Poems.

92. Henry Miller

It's fun to talk about Henry Miller at parties, and it took us a long time to realize that those who denounce him first made their acquaintance with Miller's least representative work, Tropic of Cancer. It's an important book, but mainly for the history of American censorship. The correct way to fall in love with Miller is through his exquisite nonfiction, most notably The Collosus of Maroussi and Big Sur and the Oranges of Heironymous Bosch.

91. Robert Heinlein

Morality without end, purpose in the unreal. He got so much better as a writer you can imagine him as one of his humble characters, toiling endlessly at something larger than himself and maybe impossible. Is there any more fun you can have than Stranger in a Strange Land? To Sail Beyond Sunset? The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress? Starship Troopers? His juveniles are in some ways even more brilliant, bringing his dream of the stars to audience poised to inherit it. Recommended reading: Farmer in the Sky, Tunnel in the Sky, Between Planets, Citizen of the Galaxy

90. Lorine Niedecker

She was a recluse from Wisconsin who loved the Imagists. She wrote to Louis Zukofsky, she kept writing in her bizarre island home. Her nature poetry is better than anyone else's nature poetry, her confessional poetry is fresher and more accessible than Plath or Sexton. She was funny, and could be so sad. She is the marvelous product of a strange and relentless world. Recommended reading: "For Paul", Collected Poems.

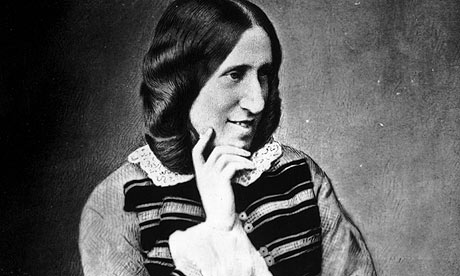

89. George Eliot

Born Mary Anne Evans in 1819, she wrote Middlemarch, Daniel Deronda, and Silas Marner, a threesome that must rank with any of the finer achievements of realism in fiction. Yet her breadth of character and theme took on so much more. This is a writer that had common sense, verve and intricate knowledge about the unfolding of human events. Eliot's ouvre is astonishingly mature for its time, and remains readable today.

88. David Mamet

The quintessentially Jewish-American dramatist, his conquests of poetry and fiction were minor. But he exploded the idea of the American play, creating an exciting new vernacular that brought crowds, excitement and controversy to the stage. Famous for shutting down an all-female production of his masterpiece Glengarry Glen Ross, Mamet is an able theoretician, and maybe the most important Chicago Jew of all time. Recommended reading: American Buffalo, The Duck Variations, Boston Marriage.

87. Derek Walcott

Born on the island of St. Lucia in 1930, Walcott is the most important poet of the Carribean, and an enduring voice in international letters. His epic poems, bringing classicism to new places and forms, are major, and his command of the short poem is as adept as Auden's, a man Walcott admired greatly. His "Eulogy to W.H. Auden" gets us every time. Also, Walcott's achievements in the theatrical realm are not to be overlooked. Recommended reading: Omeros, The Arkansas Testament.

86. Isak Dinesen

Denmark's greatest writer, she was born Karen Dinesen, and she would write about the strangeness of her life in Kenya with her husband. Carson McCullers arranged for her to meet Marilyn Monroe; they danced on a tabletop together. She wrote "Out of Africa" about her time with her husband in Kenya; "Babette's Feast" was her finest story. She was more delicate with her prose than her storytelling, but both are worthy of a place here in this best of all possible lists.

85. Maryse Conde

She is to the novel what Walcott is to the long poem. Her intricate templates for Carribean novels are massively impactful reimaginings of Western themes, replete with other places and attitudes that she experienced. Better than John Irving or Richard Price, her chronicling of the French attitude towards its possessions is her very autobiography. Recommended reading: I, Tituba: Black Witch of Salem, Crossing the Mangrove, Segu.

84. Joyce Cary

Relentlessly funny, incredibly inventive, and one hell of a writer. His comic trilogy was the height of modernism at the time. A voice that comes from the future, born with knowledge of the past, buoyed by the good humor of the present. The much-traveled Irishman wrote the most sterling address to colonialism we ever had. But mainly, he loved being an artist, and he was one of the finest his country would ever produce. Recommended reading: The Horse's Mouth, To Be A Pilgrim, Mister Johnson.

83. Frank O'Hara

The gay American New York poet whose confessional and addictive personality made him funny and fast. He wrote some of his poems in a room with his friends; he fucked well and seriously; he redefined the modern by looking in the mirror. Sure he has a few misfires, but he's so fearless, never afraid to take chances, to say something more revealing of himself than is absolutely necessary. Recommended reading: "A Step Away From Them", "Autobiographia Literaria", the new Selected Poems.

82. Gabriel Garcia Marquez

His story A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings is a great relief to high school kids everywhere, its magic remedy to the stale fare of English authors overstuffing their textbooks. Not sure what his master fiction 100 Years of Solitude is meant to remedy, but every college kid from Los Angeles to Prague has a copy. Amazingly he is still alive, although he does not write anymore. He said his piece. Recommended reading: The Story of A Shipwrecked Sailor, An Evil Hour, The Autumn of the Patriarch.

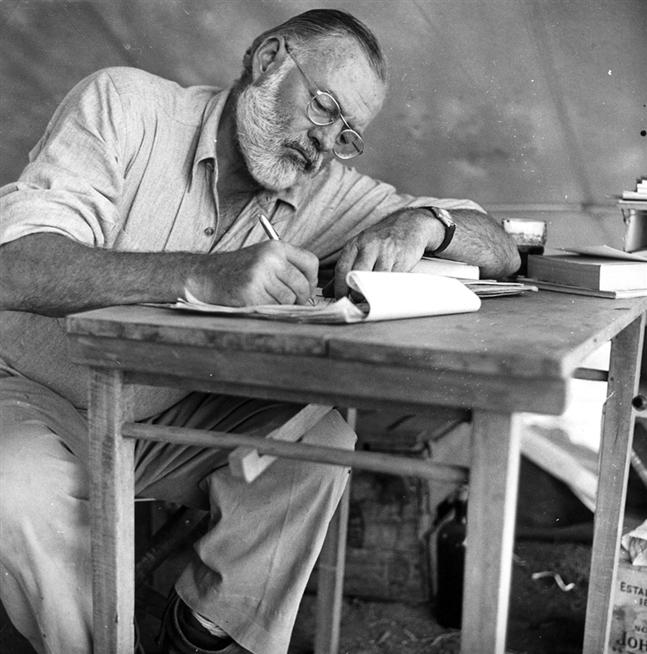

81. Ernest Hemingway

He was a talented novelist and short-story writer who was larger than life. Like his less talented peer F. Scott Fitzgerald, his writing can occassionally seem dated and stale, but there is no denying his influence, and his finer work ranks with the supreme achievements of American fiction. "Hills Like White Elephants" is great the first time you read it, but only the first time. This remains true of much of his works. We find it strange to think he was made of flesh and bone, and not smelted parts of several decrepit Civil War era bronze statues. Recommended reading: A Moveable Feast, A Farewell to Arms.

80. Carson McCullers

Her masterpiece The Heart is a Lonely Hunter was an immediate literary sensation. Rarely is an important work so quickly recognized as such. She wrote in a distinctly American idiom but her characters and themes were flawless and important. After World War II, she lived mostly in Paris. The Member of the Wedding is a slip of genius, a novel in which we can believe.

79. Flann O'Brien

The Irish novel was never the same after this man conquered it. Between At Swim Two Birds and The Third Policeman, O'Brien wrote the road map for experimental fiction, pulling the language apart before putting it back together again. Born Brian O'Nolan, he married a typist. He is the mad master, and his influence and import reigns supreme today, where his novels are still among the funniest, most inventive things ever to appear in English. Recommended reading: Flann O'Brien At War: Myles na gCopaleen 1940-1945.

78. Julio Cortazar

Half-Belgian, half-Argentinian, he was the modern master of the experimental novel. Hopscotch is the most infuriating, the funniest, most inventive. His parents split up, he dropped out of school. He later died of leukemia. His titantic efforts in the short story genre have little competition in any era of history. Cortazar gives the lie to the idea that there are many different literatures by making one of them all.

77. Saul Bellow

The greatest novel of the 1950s begins, "I am an American, Chicago-born." The Adventures of Augie March makes The Catcher in the Rye look like a fucking children's book. He followed it up with a lively collection of novels that rank with the modern masters. A little less success might have challenged him better, but as it is, he's the greatest Jewish novelist of the 20th century, and that ain't bad.

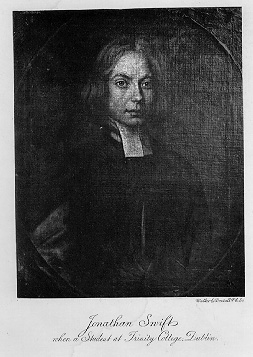

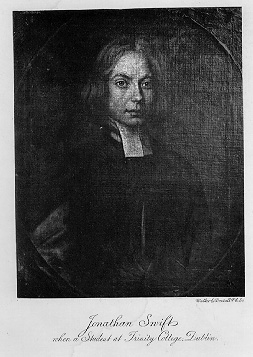

76. Jonathan Swift

He survives among his satirist peers for distinctiveness of vision and the impact of his classic essay A Modest Proposal, and the wonderfully still-readable Gulliver's Travels, which basically foretold all of modernity better than anyone else ever would or could.

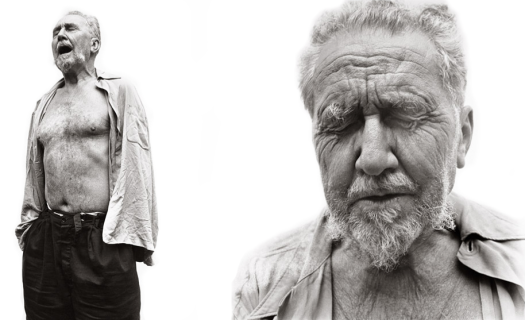

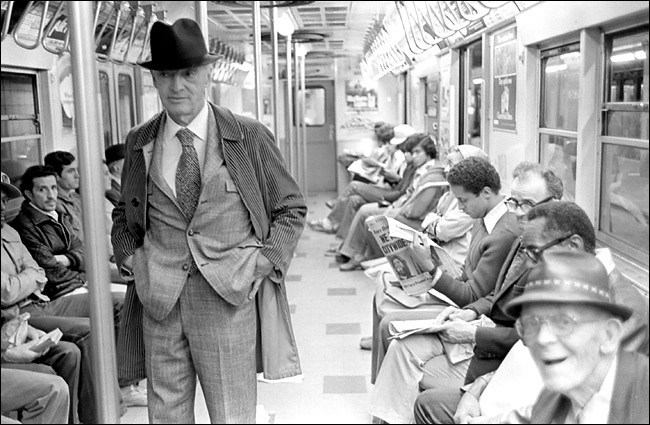

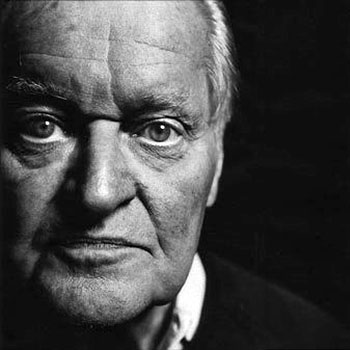

Ezra Pound photographed by Richard Avedon75. Ezra Pound

Ezra Pound photographed by Richard Avedon75. Ezra Pound

Somewhere between the worst person who was a great poet and the greatest poet who was an asshole sits Pound. After living with Yeats in Stone Cottage, Ezra Pound married an artist named Dorothy Shakespear. Previously, he had been engaged to Hilda Doolittle. In Paris, Hemingway taught him to box, but he decided to become a composer instead. He fell in love with the only violinist who could make sense of his compositions. Later, in Italy, the two would try (and fail) to write a detective novel in the manner of Agatha Chrystie. He then spent 25 days in a cage outside Pisa for hating the country of his birth. His poetic innovations and sense of the lyric are actually somewhat underrated, and The Cantos must be the great long poem of the 20th century. It will never be in Oprah's Book Club, but then again neither will any book of serious poetry. The first 50 copies were printed on lambskin.

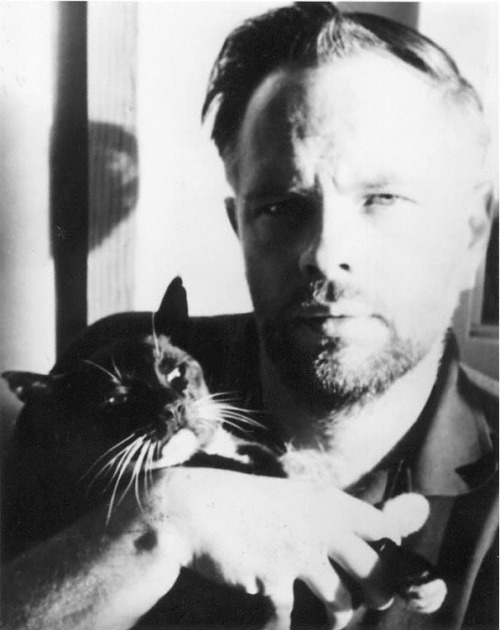

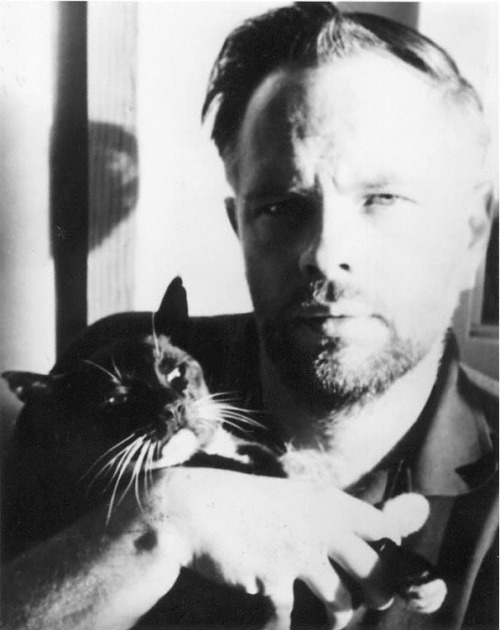

74. Philip K. Dick

Oh Philip was the conjurer, the mad genius. The completely humane. In The Man in the High Castle he dismissed fascism with the cautious wave of a hand. Was he the greatest prose stylist on two feet? No, but he had his pathos—the lost, last moments of A Scanner Darkly, the incredible pull of Ubik. He was like a free object spinning in zero gravity: Radio Free Albemuth; his stories are so endlessly inventive it is like he was starting them from scratch. Paranoid fuck.

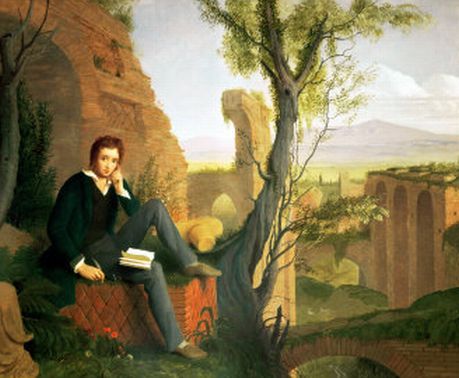

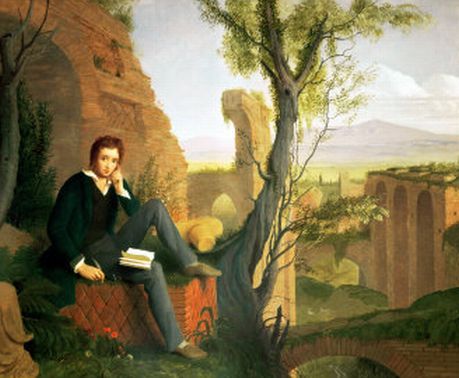

73. Percy Shelley

Attended Oxford; read sixteen hours a day. It worked—he would write lively novels, and poems that were representative of the time and the place, and went beyond it. Seems to have survived his Wordsworth obsession, as many after him would not. He wasn't that popular during his lifetime, but his reputation lived on, and his work would remain a touchstone for poets and fiction writers in the two centuries after his death. Recommended reading: of the lyrics, we prefer "Ozymandias" and "Ode to the West Wind"; the long-form and dramatic verse reached their apices with Prometheus Unbound and The Cenci; the early Gothic novels, most notably, Zastrozzi, are a good companion on a stormy autumn night, but you'll never find a copy.

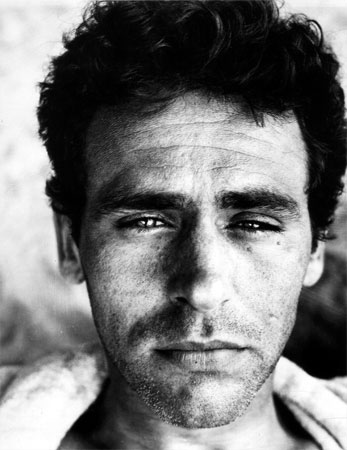

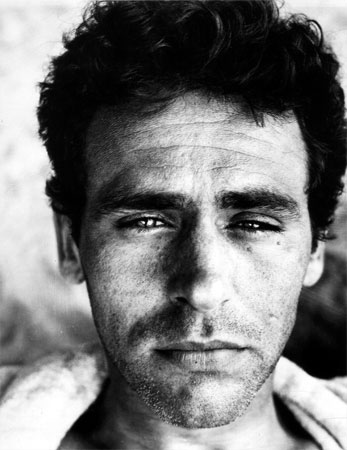

72. James Agee

The foremost journalist of his era, he also wrote a tremendous novel, A Death in the Family, and the bible of creative nonfiction, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Had an important side career as a screenwriter; but in the main he wrote many of Life magazine's most enduring pieces with Whittaker Chambers. One of those sad, great-looking literary demigods who died in a taxi cab before his 50th birthday.

71. Stanley Elkin

The greatest American comic novelist, Elkin was one of the smartest people ever to live. His stories are a blossoming achievement, a dramatic victory of non-realism in the dreary bog of American fiction. He is incredibly underappreciated and all of his novels deserve revisiting. It was in the stories that he really shined, always avoiding the easy resolution, always being more moral with other people than he would be with himself. He was a master critic, a polished prose stylist. Recommended reading: Mrs. Ted Bliss, Searches and Seizures, The Franchiser, A Bad Man.

70. Walter Benjamin

A German Jew who redefined how the essay should operate. Was killed by Germans in a hotel room running from the Nazis, or he could have just committed suicide. Translated Proust and Baudelaire. His ideas about art pretty much all came true, eventually. Skilled consumer of hashish, of bearing down on some truth you did not know was there but would have come to the surface eventually, probably, without him.

69. Harold Pinter

The greatest English dramatist of his time, we have taken so much from his clipped ways of saying, his extraordinary grasp of how the theater operates and how it ought to operate. His ideas have been stolen by Larry David and Quentin Tarantino and Wes Anderson, a testament to their timeliness. Married to Antonia Fraser, his political views weren't always to my taste, but he was a fierce proponent of freedom at home and abroad, and helped many writers on that account. Recommended reading: The Dumb Waiter, The Homecoming, The Birthday Party, his novel The Dwarfs.

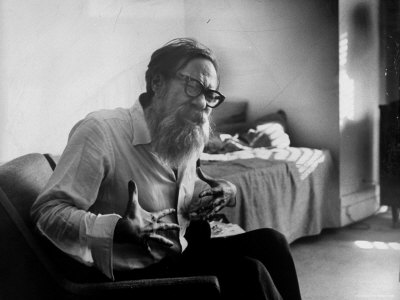

68. John Berryman

The Dream Songs is one of the top 5 poetry manuscripts ever written, bringing character and voice to new hights in American verse. He was born in 1914, he committed suicide in 1972. The between years were drunk and hard, but the poetry came easy. His father killed himself when he was 12, from that he basically never recovered. Recommended reading: Dream Song 34.

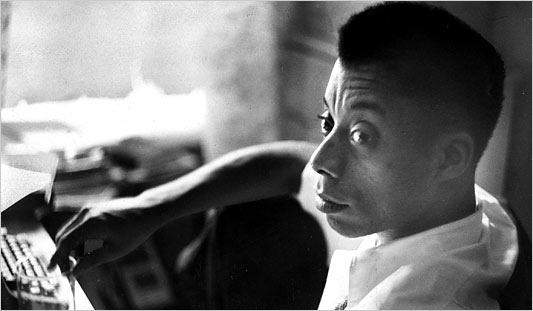

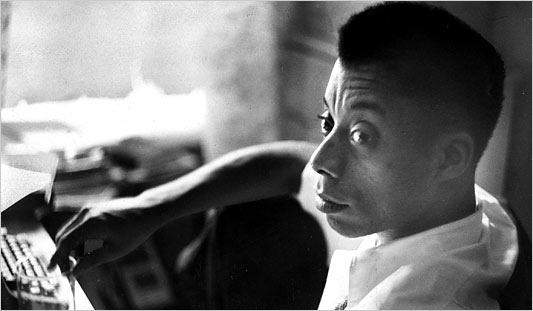

67. James Baldwin

Born in Harlem, he was gay, black and brilliant. His novel Go Tell It On The Mountain is a work of incredible depth and sensitivity, probably the second-best novel of the 1950s and one of the ten greatest novels of all time. His short story "Sonny's Blues" might be best remembered. It holds up better than any short story you'll find in a rag like The New Yorker. He needs a renaissance more badly than most.

66. Tu Fu

The greatest of the Chinese poets, he is a master in any time. Chinese schoolchildren still recite his verses, as do their businessmen. Claimed to have lived in a "straw hut," but really it was just another one of those upper-middle class two story affairs on a whispering brook like they had in those days. Kenneth Rexroth's 100 Poems From the Chinese is pitch-perfect, and includes all of the memorable Tu Fu.

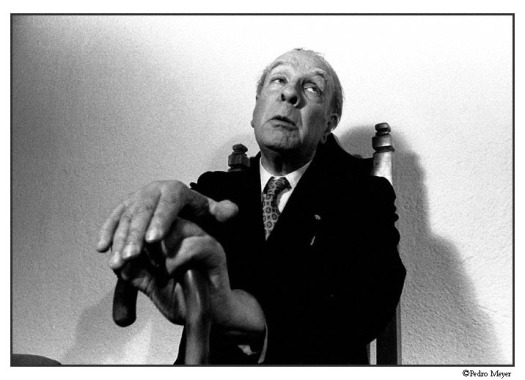

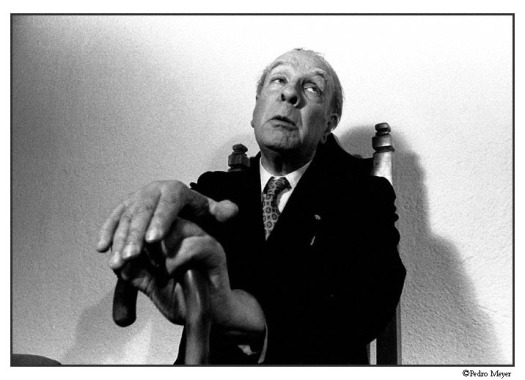

65. Jorge Luis Borges

A blind, deep thinker. His stories are endlessly rewarding and entertaining. The genre of science fiction virtually does not exist without him. Astounding how often a gunshot or a stab wound ends these tales, but still, Comp Lit programs across the Northeast would be a lot poorer, and certainly a lot less sexy, were it not for this man.

64. Malcolm Lowry

He was a crazy and he was a drunk, but he managed to outwrite most of the non-crazies and non-drunks despite spending his days chronicly impoverished. Under the Volcano is up there with Ulysses, with Molloy, with Light in August. Its narration is unchallenged for veracity of human feeling and expression. He was never much good at living, but through his work he'll live on for centuries.

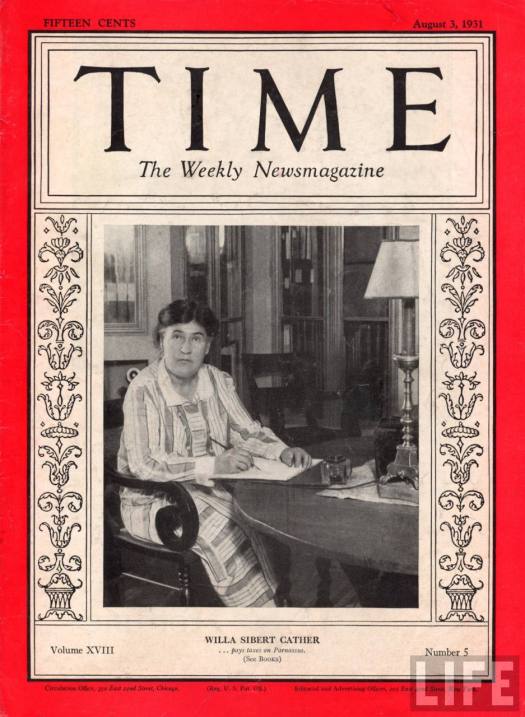

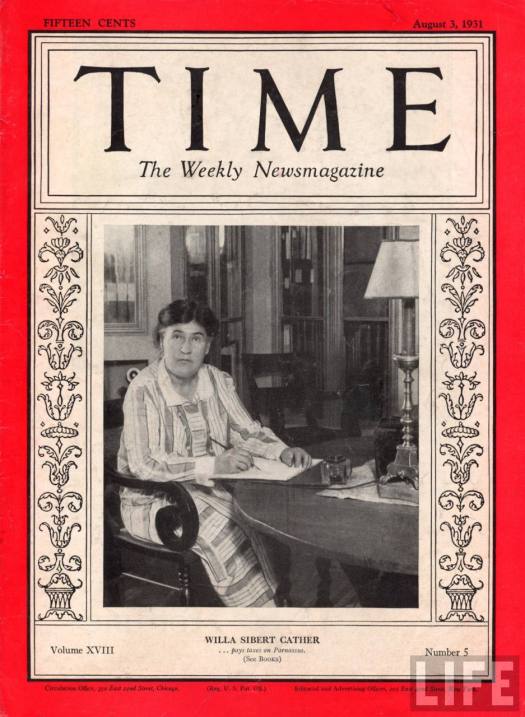

63. Willa Cather

An American lesbian. She was Episcopal, an American original. The glories can be found in The Song of the Lark, O Pioneers!, The Professor's House. Her ways were sometimes new, sometimes old. She wrote about the people that existed, that she knew, that had never before made it to these pages. Recommended reading: Death Comes For the Archbishop, My Antonia.

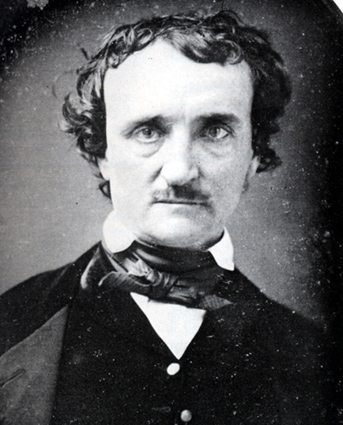

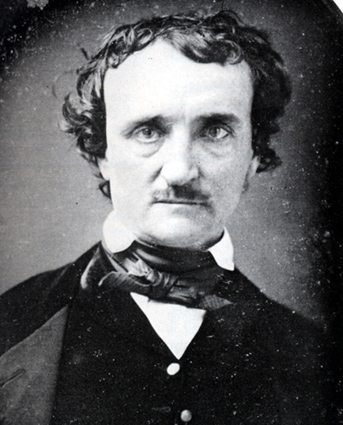

62. Edgar Allan Poe

Horror we needed, craved. The short story was brought to entertain in his mode, the beating heart someplace you weren't sure was there, his inventiveness and sense of menace. An American simultaneously at its most base and most necessary. The poetry is repetitive but sublime, largely centered upon his 13 year old cousin, whom he married. Our kingdom by the sea, indeed.

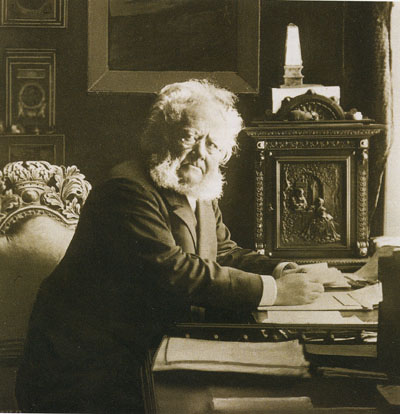

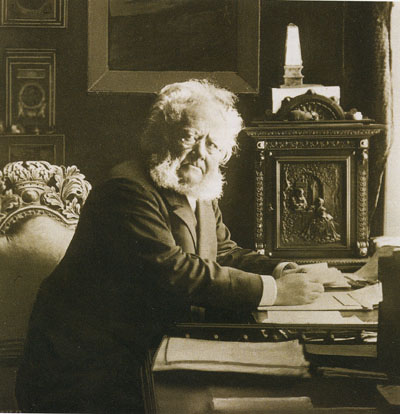

61. Henrik Ibsen

Torvald! He was a master of character, of menace. His drama was challenging, exciting, and his outlook was more shits and giggles than devotion and God. Extremely prolific, he managed so many excellent dramas, slamming Victorian morality, forging his own. Recommended reading: Hedda Gabler, Ghosts, The Master Builder.

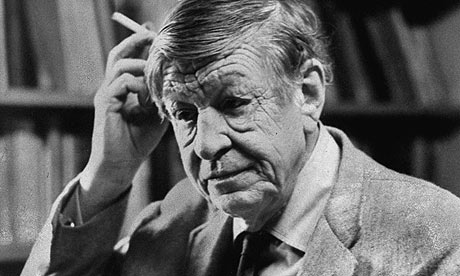

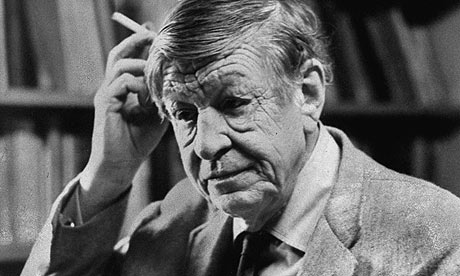

60. W.H. Auden

He was the most acclaimed poet in the world while he lived. He seems sort of old-fashioned now, but that doesn't dim his impossibly wide view of human existence, his innate knowledge of history, his incredible sense of the possibilities of the lyric. It is now assumed that he was gay, but how, really, could a poet of his time not be. Students of verse should be forced to transcribe, memorize, and possible have tatooed on their rib cage Mr. Auden's September 1, 1939. Just a tremendous poem, a model of unacknowledged legislation.

59. Thomas Pynchon

An enterprising American fabulist whose self-imposed retreat from the public sphere probably venerates him more than it should. Mason & Dixon could be praised or reviled; it was a massively courageous undertaking, a screaming across the sky. Worked at Boeing for a time. After publishing V. the greatest first novel ever by a human, he wrote to his agent. "If they come out on paper anything like they are inside my head then it will be the literary event of the millennium."

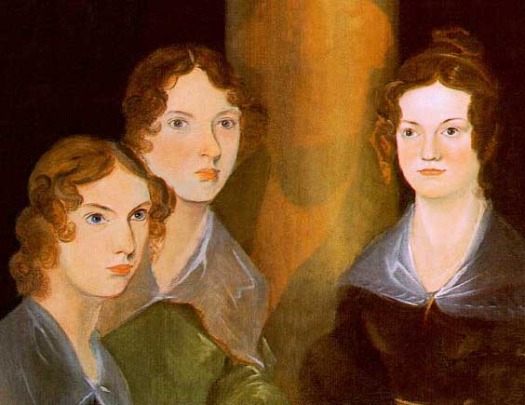

58. Emily Brontë/Charlotte Brontë

The first wrote Wuthering Heights, which has survived more splendidly than any story we can think of. She barely lived long enough to write anything else, but what else exactly did she need to write? She'd written Wuthering Heights: that was enough. The second discovered her sister's talents, and became the more prolific of the two.

57. Flannery O'Connor

She was a faithful practitioner of an emerging style, a slyness, an understanding, that exposed the depth of human character in her moral gaze. Redefined the American short story, repudiated the saccharrine elements that had defined it and gave fiction a seriousness of purpose that resonates decades after her passing. Recommended reading: "Everything That Rises Must Converge", Wise Blood, "A Good Man Is Hard To Find"

56. Leo Tolstoy

Born to the aristocracy of Russia. His cousin was Alexander Pushkin. Managed to pen Anna Karenina, the greatest novel ever written in Russian. Flaubert said, "What an artist and what a psychologist!" His endings were legend, his characterizations revolutionary. He was an accomplished political writer, and espoused nonviolent resistance. His autobiographers are very dated, but his correspondence has held up far better. Maxim Gorky's "Reminiscences of Tolstoy" is the only way to know this talented, magical novelist, this anchor for Russian literature as the world knows it.

55. Tennessee Williams

The nature of his art was evident from the very first. You could walk into a performance of one of his plays and you would know instantly that it belonged to him. His characters were darts of light, flickering across the stage, surprising even themselves. His sister was a schizophrenic, his lover was a Sicilian navy man. He brought his tendrils of genius to wherever and whenever he was. He choked on cap from a bottle and perished in 1983, the year we were born. His short stories are surprisingly revealing, like a Rosetta Stone for the sheer madness of his plays. Love the one-acts.

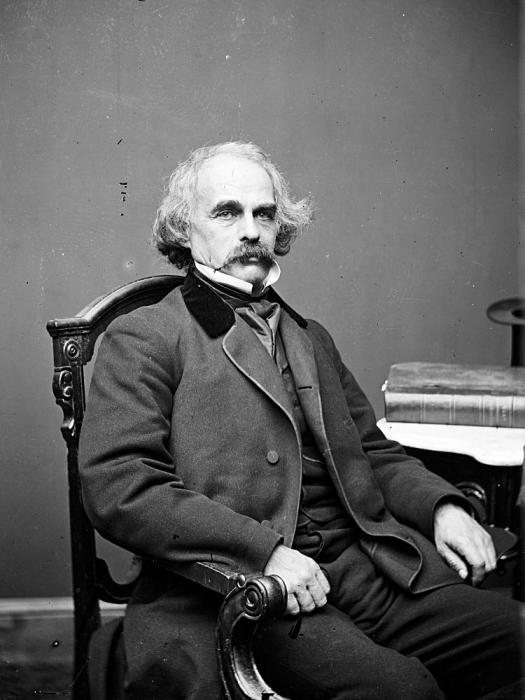

54. Nathaniel Hawthorne

Why did America become the finest country the world had seen to that point? Its artists played a crucial role. In his incredibly perceptive stories and novels, Hawthorne achieved heights that were reserved for the European masters before he brought his insight to bear on them. We'll never forgive him for how he treated Melville late in their lives, but the penning of phantasmagorias like "Young Goodman Brown" are enough to forgive most of his other personal failings. We've always though that the crimson A in The Scarlet Letter stood not for Adultery but for American, and it makes sense—we would be living in a different country were it not for this book.

53. T.S. Eliot

Terrible playwright. Also, it's probably about time for everybody to admit that The Waste Land is totally boring. Four Quartets, on the other hand, is enduring poetry. As are a handful of his other shorter lyrics, and probably the one about J. A. Prufrock. The twentieth century would have been more beautiful had he not lived, but still, the twentieth century happened the way it did, largely because of him. Oh wait, that was Hitler. Same difference.

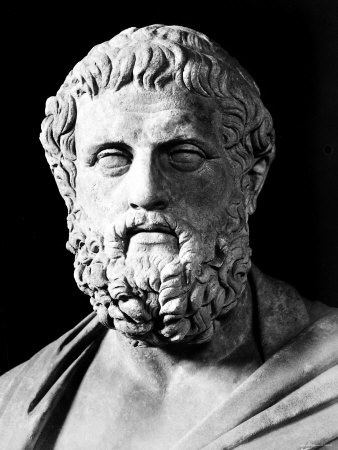

52. Sophocles

Born a few years before the battle of Marathon, he would be the second of three playwrights to rock the ancient world to its core. Banged many young boys in his times, the greatest writer-pedophile who ever lived. The magic of the Theban plays; the lyricism of Oedipus, psychology's first tragic hero. In even dealing with myth strived towards naturalism, beginning the slow march towards the reality of things. Recommended reading: Antigone, Oedipus at Colonus.

51. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

His drama Faust begins in Heaven, has a poodle turning into the devil. He was born in Frankfurt in 1749, and he'd live long, to the age of 82. He became an international celebrity at the age of 24 with the publication of The Sorrows of Young Werther, a fact he would live the rest of his life regretting.

50. Toni Morrison

Let's not let a couple clunkers haunt how clutch Morrison was in gems like Song of Solomon, Beloved, and The Bluest Eye. Her explanation of the American midwest; her command of place rivals Faulkner in its better moments. Does she sometimes adhere too closely too symbols? Is she sometimes more complex than she ought to be? That is no blemish on the career of an immortal voice.

49. Charles Olson

America's Bard, the voice of New England. Incredibly tall, incredibly wacked. He is the father of much of the American verse that directly followed, but he would never know just how lasting his work would be. He is our poet of the future, a deep thinker who lacked empathy for everyone but himself. Self-involvement can became a kind of genius at this depth, or so we hope. Recommended reading: "The Post Office", The Maximus Poems, "The K".

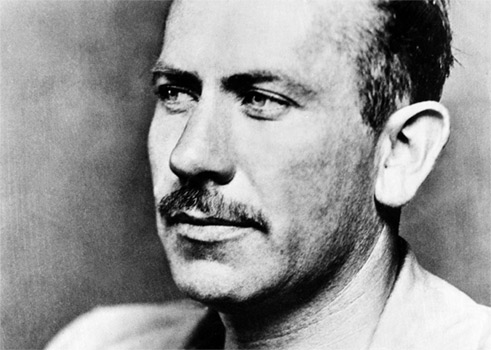

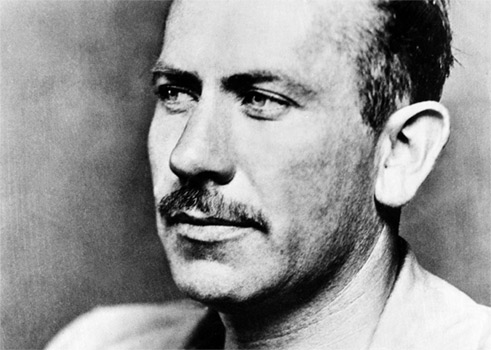

48. John Steinbeck

Steinbeck never graduated from Stanford. For a time, he worked as a handyman. His shorter works are incredible forays in concentration on theme; his longer works are a pleasure to drift into like little worlds. As a journalist of war he has no peer except for Orwell, and he could be funny, and also so devastating with the world he left you in after you'd turned the last page. Recommended reading: Travels with Charley, East of Eden, Of Mice And Men, Tortilla Flat.

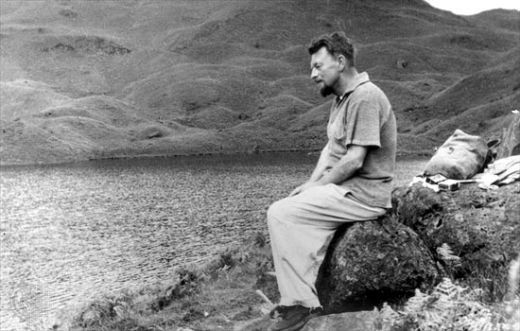

O'Neill with his second of three wives, Agnes, and their later disinherited son Shane on a beach on Cape Cod. 47. Eugene O'Neill

He wrote one comedy that made the stage — it happens to be one of the greatest stage comedies ever written, but he stopped there. His mind was occupied by the tragedy that could befall mankind, griefs personal and national. He believed the stage could depict this faithfully, and still more after that.

46. Gustave Flaubert

Madame Bovary was the real first novel, the first impulse in the form with intellectual heft, a plot with bite, a voice of reason. He wrote it from 1850-1855, and it appeared in serialized form, as the greatest novel that had ever been written at that point in time. Contracted syphilis in Lebanon. Never much of a playwright. He spawned the greatest European writer, Franz Kafka, and his evenhanded conception of the modern novel has lasted longer then his flavorful, romantic work. But without him, how were we to begin? Recommended reading: Bovary, Memoirs of a Madman, his letters

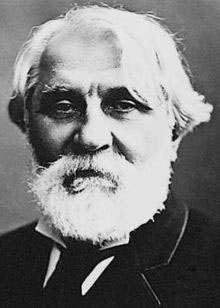

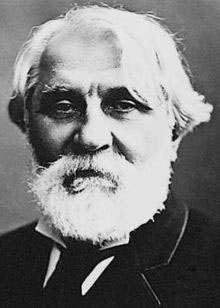

45. Ivan Turgenev

Tolstoy wrote of Turgenev: "His stories of peasant life will forever remain a valuable contribution to Russian literature. I have always valued them highly. And in this respect none of us can stand comparison with him. Take, for example, Living Relic, Loner, and so on. All these are unique stories. And as for his nature descriptions, these are true pearls, beyond the reach of any other writer!" Tolstoy could be such an understated dick at times. Recommended reading: Fathers and Sons, The Diary of a Superfluous Man

44. Charles Baudelaire

He was the quintessential mama's boy. He went looking for his mother in almost every prostitute in Paris, contracting all manner of sexually transmitted diseases. Fortunately the only effect these STDs had on his literary talent was, if anything, to enhance it. Among his Parisians his reputation became pretty solid. Proust loved the guy. You can be a dandy and a genius, and one hell of a poet. He was. Recommended reading: The Flowers of Evil, Paris Spleen, Artificial Paradises

43. Robert Lowell

Of the New England poets, his achievements were the serious kind. He mentored many other greats, but his fidelity to his own vision, his moral look at the world he lived in, whatever it looked like to others, was firm. His sonnets are the greatest besides Shakespeare's. Recommended reading: For the Union Dead and Life Studies.

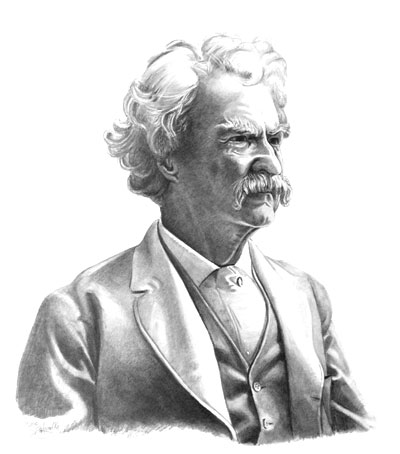

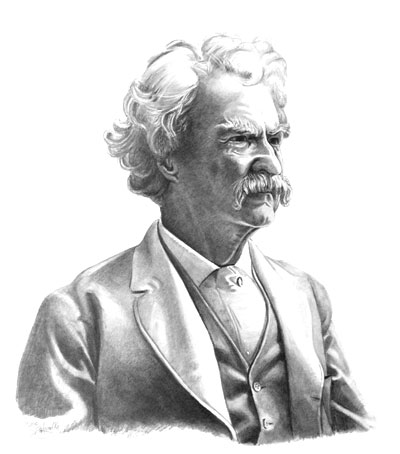

42. Mark Twain

Aphorisms and all, Twain was an American as great as Lincoln or Leadbelly. That is, deeply rooted in the land of his birth, yet unblemished by either bias or zealotry. Tom Sawyer is for kids, but Huck Finn stands up to any other novel in this bastard language of ours. He is evidence that this country should be.

41. Robert Creeley

The German psychoanalyst/aphorist Bert Hellinger said that "rejection leads to resemblance," and it is this fact that best characterizes Creeley's career. He turned away from and overcame the sentimentalists, redefined what the country called sentiment, and broke free again, a man who could not die without knowing every version of love. The first three books are indispensable—The Charm, For Love, and Words—though there are later gems like Mirrors and Life & Death. The man is also our most imitable poet, which if the converse of Hellinger's words is also true, make Creeley a signal father of this country's next generation of original writers.

40. Iris Murdoch

What an inspired philosophical novelist! She wrote things down that should have been already written down, with an inspired moral sense. She was born in Dublin and her husband and life partner John Bayley at Oxford. They made an irreplicable team. She would elevate discourse to a heavenly routine. Recommended reading: A Year of Birds, The Black Prince, The Sandcastle, The Sea, The Sea.

39. Arthur Rimbaud

The boy poet is a familiar role, but Rimbaud was the greatest of all boy poets. Died shortly after his 37th birthday. Wrote to and fucked Paul Verlaine. He was tall, thin and bony. Breton called him "a god of adolescence." He wrote poetry briefly when he was in his teens. One man's passing fancy is acknowledged as an titanic masterpiece by another man. It is best to read John Tranter's appreciation of him and see just what we mean.

38. Mary Shelley

Created the most important novel of its century, the Pygmalion-inspired Frankenstein. It is still fabulous reading today, and inspired more than almost any other work of fiction. It is about man becoming the machine, and it identified the chief feature of life thereafter — technological innovation and how it would change humanity into something different than it was before. For this Shelley made the perfect story, one that is more than a metaphor, it is a koan to what has yet to occur.

37. Virgil

Born in France when it was Gaul, Virgil was the son of a farmer. Eventually he followed Octavian and became a part of the political scene. In the last ten years of his life, he composed The Aeneid. Its address to Homer is evident. He saw his father go blind, his two brothers die, one at childbirth, and one in a messy accident. He was the greatest writer of his time, and were he here today we could reasonably account for him as the inventor of what would become Western literature.

36. Emily Dickinson

Quietly, unobtrusively, she is the American poet, giving more to those that followed her than anyone else. She is in every poet we read, every word that is written. Even when she is not, she is there, in her lacks. She eschewed the long vision of some of the finest poets in English, but no one did more with less, and this was her genius, along with something of a bitter wit. A person can be alone in the universe, and yet as long as they have literature, they need never worry.

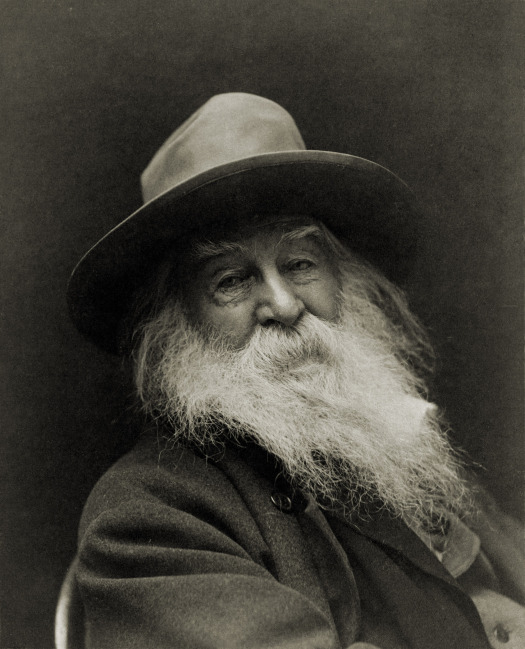

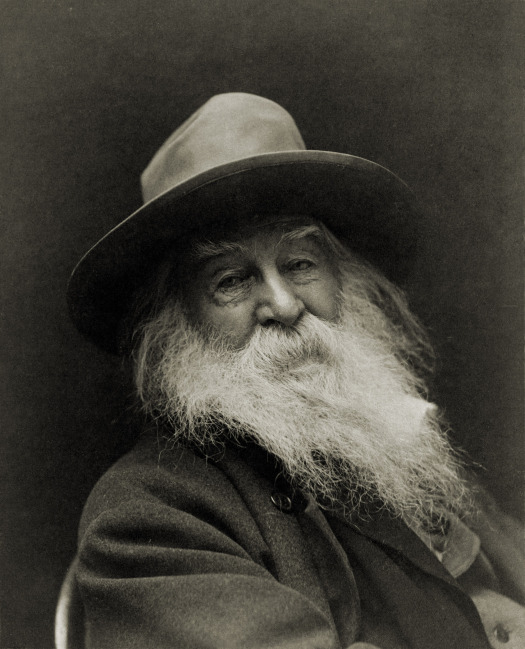

35. Walt Whitman

America's most delightful poet, Whitman has had a renaissance that many already saw coming. His verve and vision are so far ahead of any of his peers, it's a wonder he wasn't hailed earlier. He never drank. In his great letter to Emerson he imagined an America greater and more important than we could even conceive of today. He was born on Long Island. He hated slavery. He worked at nursing, journalism, homosexuality, teaching. Recommended reading: "O Captain! O Captain!", Leaves of Grass, his notebooks.

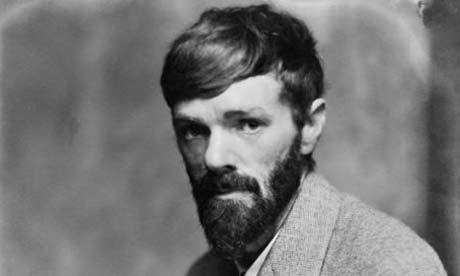

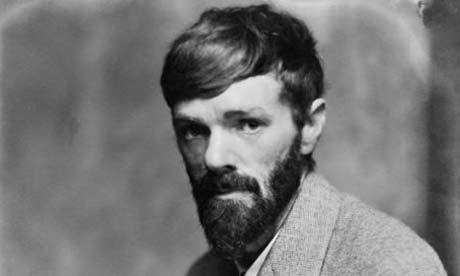

34. D.H. Lawrence

He died in France in 1930, but his final resting place is in Taos, New Mexico. It is a strange and wonderful journey for the English transplant. He called his life a savage pilgrimage, he was never given the right sort of attention in his lifetime. As he walked through the streets, they should have bowed. His criticism is above reproach, it is more a blog than any blog that has yet been created. His novels and stories are fresher today than the day they were written. He can be put down easily, but he is easy to love, too. Recommended reading: Lady Chatterly's Lover, Women in Love, essays.

33. William Carlos Williams

Why is the New Jersey native so important to the project of American poetry? Why is he more than just "The Red Wheelbarrow"? Why is his Spring and All one of the ten greatest poetry manuscripts of all time? Like Pound who he hated, Williams' aims were new and real. They were the everyday, they were the eternal. His ear is flawless, his grasp of both prose and poetry on the level of Shakespeare. He is the greatest poet this country produced from its small towns, where he served as a doctor. Recommended reading: Spring and All, "Danse Russe", "This Is Just To Say", Paterson

32. Samuel Coleridge

Addicted to opium, he was one of the great critics, and you then you get to his creative work. For their magical form and incantatory meter, Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla Khan have no peer. Didn't have the best relationship with his mom. Was an innovator with blank verse, set the template for confessional poetry and much that came after. He wrote Rime, he could napped for the next hundred years and he'd still be at the top of his class.

31. Henry James

Other than Charles Dickens, did the novel ever have a more devoted and able practitioner? Born in New York City, his highfaluting education took him across Europe. Gay as the day was long, he hit on Hans Christian Andersen when he was 56 and Andersen just 27. Whether it was dark comedy or darkest tragedy, he was at his efficient best. With "The Art of Fiction" he planted his flag in the territory of made-up people and places. They would never be the same after. Recommended reading: The Portrait of a Lady, Wings of the Dove, The Bostonians.

30. John Keats

Before everything, he was the greatest letter writer ever, his collected correspondence only potentially exceeded by that of Franz Kafka. His dad died after falling from a horse. He moved to Italy because of his fear of succumbing to tuberculosis. He succumbed in 1821. His poem "Endymion" began "A thing of beauty is a joy forever," and went on from there. The advances he made, the heights he reached! Recommended reading: his Odes, "Sonnet to Solitude", Calidore: A Fragment

29. William Wordsworth

There was the motivation to write in the voice of the people. Coleridge tried to say that drugs were the better path. Bill refused, citing Caedmon, the stable-boy that initiated our poetry. He was the best when he walked the country-side with Dorothy. Emotion recalled in a moment of tranquility was a cute idea, but it really only worked in the case of the daffodils. No one tried harder, and no one failed as beautifully, as this master.

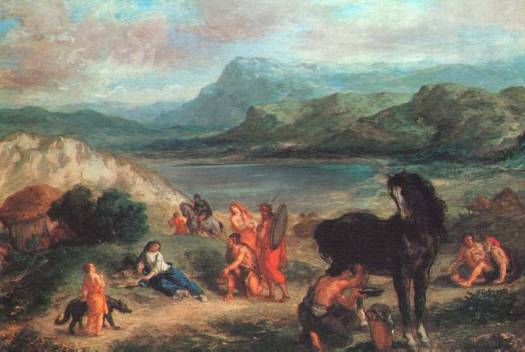

Eugene Delacroix's 'Ovid Among the Scythians'28. Ovid

Eugene Delacroix's 'Ovid Among the Scythians'28. Ovid

It is difficult to mark these Ancients. There is considerable import in coming 'first', but that is not what this list is measuring, we are saying who is best. Invented eroticism. He revealed himself in his many poems, creating an idea of art that would outlive him and every other member of his civilization. Born to an equestrian family, he married three times. Invented eroticism.

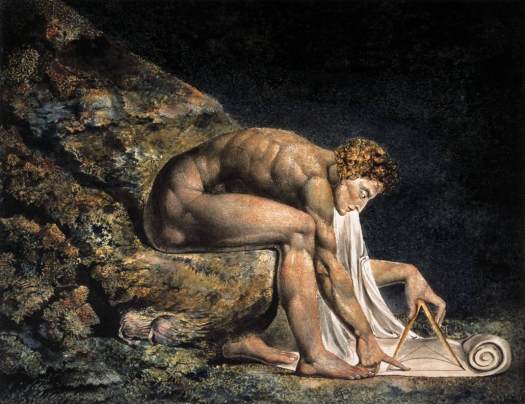

27. William Blake

He was considered insane by his peers. Songs of Innocence and Experience showed off his maturity and a poet, and that he was an inspired illustrator. He did not hold with the doctrine of God as Lord. He taught his wife to read, write and to use a printing press. We are still waiting for the poet who can draw like this to come back to us again.

26. Dr. Johnson

His life basically invented the concept of autobiography, he had mild Tourette's, after college he went home and lived with his parents, his father ran out of money. He wrote the dictionary, he wrote columns. The breadth of his knowledge was spectacular to behold. Finally the 24-year old King George III granted him a pension of 300 pounds a year for basically civilizing some small part of humanity. Recommended reading: An Account of the Life of Richard Savage.

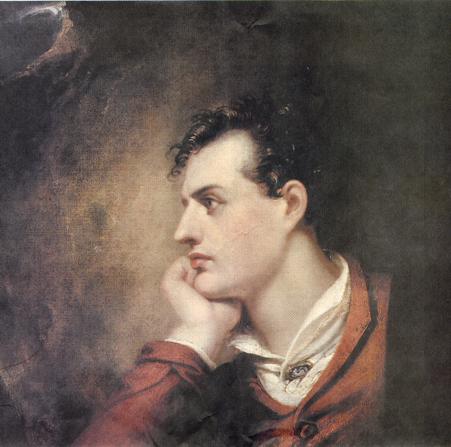

25. Lord Byron

Described by Caroline Lamb as "mad, bad, and dangerous to know." Did everything: ran a newspaper with Shelley, courted all the pertinent ass of the period, a hero to Greece, to the English speaking world. Don Juan was his fun epic: it lives and breathes today and should be more widely read than it is. Had a massive temper, suffered from depression, a hearty bisexual. Such ingenuity in the old forms was rare and special for a creature of his time. Recommended reading: The Island, Heaven and Earth, Manfred, Darkness.

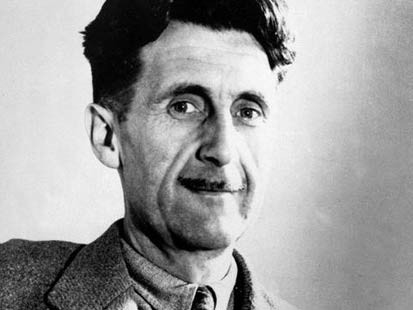

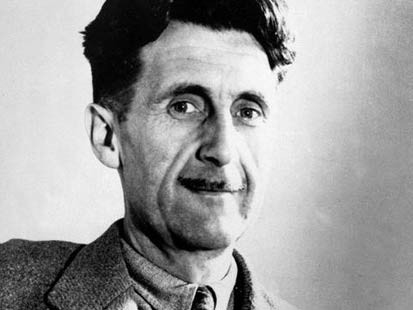

24. George Orwell

He created the modern essay, he politicized it and de-politicized it; lambasted communism for the evil that it was, became property of the American right and American left in equal measure. He left behind novels that are widely read today for both their literary merit and virtues as stories. He was the bearer of bad news, the hearty messenger, for all that our current slate of modernity portends. He was in favor of what was right. Recommended reading: Animal Farm, his essays, 1984.

23. Stendhal

His heights were higher than almost any other. A vastly underappreciated genius. His memoirs, starting with The Life of Henry Brulard. It is the finest autobiography the West has generated, and if released today there would be no competition for the book of the year. Born Marie-Henrie Boyle, he was a womanizer and a pretty man, but when he set down to write, he was without peer. Recommended reading: The Red and the Black,

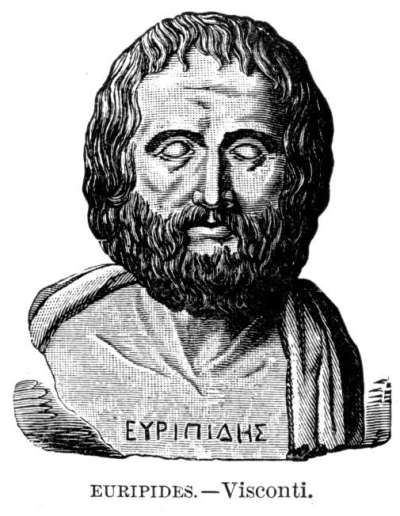

22. Euripides

22. Euripides

Before him, Greek drama was Happy Days and Good Times. He brought everything else to the table: the undermining of the protagonist, the gross inequities of fate, the importance of satire to civilized beings. All theatre was archetype before this giant, and the original onslaught of realism that he brought to the floor was a revolution. His plays, and his alone, were about regular people going about in the guise of gods. His was a deeper grasp of human nature, one imperceptible to most. When he saw a slave, he saw more than a slave. When he saw a god, he saw us all. Recommended reading: The Trojan Women, Iphigenia in Aulis, Helen.

21. Miguel Cervantes

One work summed up the entirety of Spanish literature, but oh what a work he left us with! He had to practically redo an entire language to keep up with his inventiveness. He survived three gunshots in a massive sea battle to survive to write it at all. He never regained the use of his left hand. He died on the same day as Shakespeare.

20. Laurence Sterne

The finest experimentalist ever. Smash novels, insights of incomparable erudition, hilarious, so ahead of their time that they seem more modern than most things published today. Tristram Shandy has lasted longer than its detractors. Many of its jokes have still yet to be parsed from a text thick with meaning, with comedy and profound statements of humanity in a time where it was not so easy to recognize what exactly that meant. Recommended reading: A Sentimental Journey, Tristram Shandy.

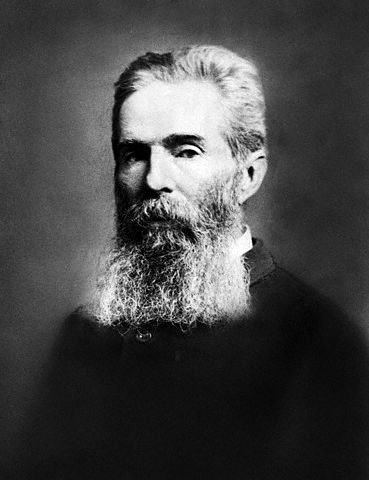

19. Herman Melville

Mythmaker, dreamer, anthropologist. Once born he took up the title of greatest writer in America and never relinquinshed it until he died in 1891. His posthumous novel, Billy Budd, was a prism of his genius. It wasn't long until the New York-born Melville was at sea. This would inspire the most exciting nautical novel in history, Moby Dick. He is admired by all those capable of admiration. Recommended reading: Typee, Billy Budd, The Confidence Man

18. William Butler Yeats

Everything was magical to this Irishman, who sympathized with the aristocracy and was never sure it was all going to work. Nominated to the Irish senate. Seminal to the creation of Irish theater in so many ways; his haunting, haunted plays that drew equally from Irish folklore and Japanese Noh plays. Every formalist poet of the 20th century owes a great debt to this man—only Hopkins can match his ear for the lyric. His obsessive drive (and eventual failure) to father an heir, combined with a keen interest in occult trance ceremonies, led Yeats to copulate with more girls less than half his age than perhaps any sextagenarian in history. His Nobel Prize in 1923 brought worldwide fame to his body of work and, perhaps more importantly, worldwide attention to the literature of the nascent Irish Free State.

17. Homer

There was a generous discussion about whether or not we should have included Cynewulf on this list, to reference whatever human mind had the most integral role in creating Beowulf. But an entire oral tradition made Beowulf, a truism that could just as easily be spoken about Homer. He lived before Christ, a time that is unimaginable to most of us. He winked into existence at about the time of the Trojan War, that much we do know. There was someone: he may not have been blind, but he saw more than anyone had up until that point, and arranged the tenuous first gasps of civilization upon homo sapiens. The rosy-fingered dawn will stick with us for eternity.

16. Charles Dickens

He did things with story in his serials that still have not been attempted as well, took formulas and reconstructed them to his purpose, he was the mad scientist of place and person, the address to the Industrial Revolution. There he was for the greatest change in human history and thank heavens we had him to stand there, backing into darkness, so we could see the light. Recommended reading: Great Expectations, Hard Times, Nicholas Nickleby

15. John Ashbery

Our modern magician, Ashbery has simply never written a bad poem, and his adventures with the epic in A Wave and Flow Chart elevated him above his peers. His command of the language is second to none, so much so that it appeared he was writing in a new language. Gay, lives in NY. His work is destined to tell the tale of this time better than any other writer alive today, and it is the words he made that tell it.

14. Virginia Woolf

Born in London in 1882, it was a very good year for a extraordinarily perceptive and sensitive woman. She saw the Godrevy lighthouse in Cornwall during her summers, and she did it: she wrote To the Lighthouse, one of the five greatest narratives ever constructed in English. Being depressed and unhappy is mere sport for the greats, Woolf had a chronic disposition: "One of my vile vices is jealousy, of other writers' fame," she said, and yet what could Virginia Woolf envy in another writer! Each of her novels begins as a small masterpiece, and then suddenly her stunning talent for voice creeps in and no matter the station or mask of the character, we feel ourselves shaken by her knowing. Recommended reading: The Waves, Jacob's Room, Mrs. Dalloway

13. Geoffrey Chaucer

Penned the relentlessly inventive and frequently hilarious Canterbury Tales, a foundation of English literature that badly deserves another 'translation' by a major voice. We'd elect Paul Muldoon, but he's too busy resuscitating the just plain awful New Yorker poetry section.

12. Dante

Born in 1265, he was the smartest man who had ever lived up until then. Called the father of the Italian language. Master of theology, the Inferno is brilliant in both concept and execution. The Divine Comedy is the masterpiece of masterpieces.

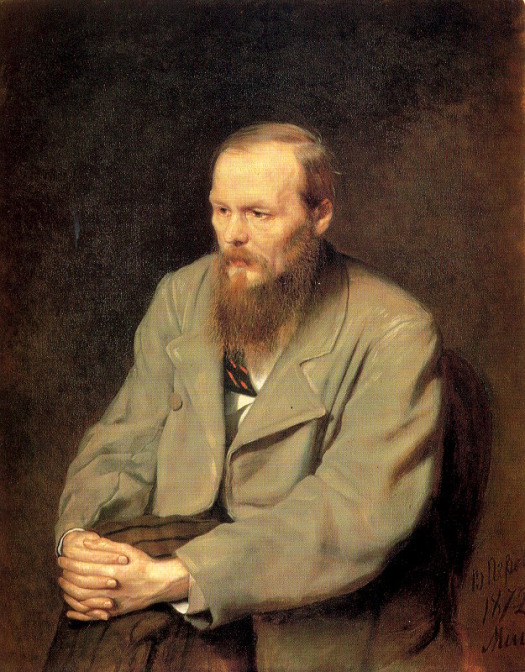

11. Fyodor Doestoyevsky

In The Double and Notes from the Underground he penned the canonical texts for the modern novel, for modern experience in general. He dug the ditch for literature to explore themes and motifs, aspects of the human existence, that had never before been attempted. As Virginia Woolf wrote, "The novels of Dostoevsky are seething whirlpools, gyrating sandstorms, waterspouts which hiss and boil and suck us in. They are composed purely and wholly of the stuff of the soul. Against our wills we are drawn in, whirled round, blinded, suffocated, and at the same time filled with a giddy rapture. Out of Shakespeare there is no more exciting reading." For that reason, Bill Shakespeare ranked higher on this list.

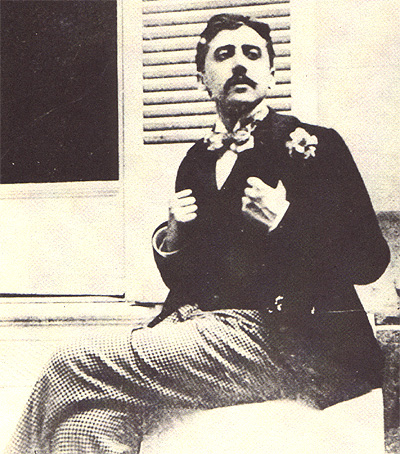

10. Marcel Proust

Was he the most exciting writer you've ever read? No, but at his best, Proust achieved the kind of highs that fiction had never before approached. Really, it wasn't fiction; it was the kind of autobiography, the sort of scale that was new and fresh. Remembrance of Things Past is so difficult to translate that it probably has not even been expressed sufficiently in English. Despite this, he took the step forward that the novel needed, and he did it for his own sake.

9. Anton Chekhov

He practically invented the modern novel, the modern short story, and the modern play. A doctor like William Carlos Williams, his vision of the sentence was serene and beautiful, and his novella My Life remains the greatest achievement in that genre. His stories mattered quite a bit; they are acclaimed by many as the best ever done in that form, and his plays are beautiful and dramatic, and so, so sad. Recommended reading: My Life, The Cherry Orchard, Three Sisters, "The Bishop"

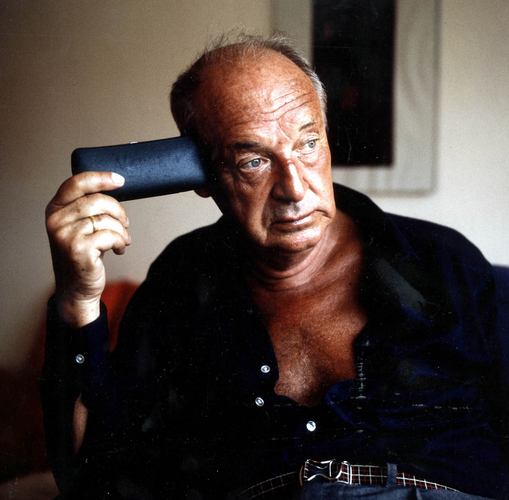

8. Vladimir Nabokov

The West's mad and zany master. Lolita is probably more important than The Odyssey. It is better written, at least. His stories are sublime pictures of the sane insane man behind the moving inventiveness of Pale Fire. Talked a good game: try his lectures. Recommended Reading: Ada, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight.

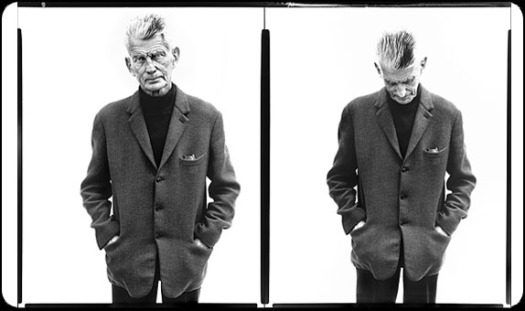

7. Samuel Beckett

Maybe the greatest prose stylist we ever had, and also the best playwright besides Bill? God never came, but he did, to read things over, survey the situation, and judge human behavior. Master of how we speak to one another, why we say the things we do. Recommended reading: Endgame, Krapp's Last Tape, Molloy, Malone Dies, the short prose works.

6. John Milton

The king of all the poets, Milton attempted the essential story of man, beginning with his rise and chronicling his fall. He alone is the master of meter, of the telling phrase. He practically invented the use of the adjective. Before dying in 1674, he was born to a Puritan family and lived his life out as a Protestant. He planned to enter the ministry but was expelled. Penned some of the most cogent political writing of the time only helps his cause. He wrote Paradise Lost while blind, and sold its copyright for £10. The greatest poet of this time or any other.

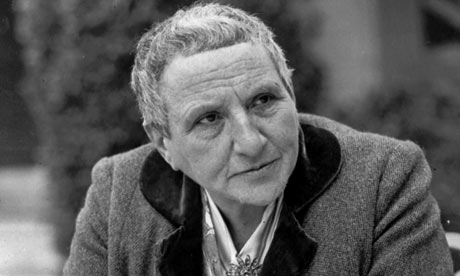

5. Gertrude Stein

To know that you have picked up something she has written, perhaps casually, or it was given to you, and to open her little world of language, where nothing was explained, and the reader had to come the rest of the way herself. She mastered being famous or notorious. Delivered those magnificent deadpan lectures. Said more in three words than most did in whole books. Recommended reading: Tender Buttons, Everybody's Autobiography, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.

4. James Joyce

We leave Finnegans Wake to the aliens to hope they can understand what we can't. But he wrote the beginnings of the short story we recognize today, the tragic and insane last moments of "The Dead." Ditto the ultimate line of "Evangeline" in Dubliners: "Her eyes gave him no sign of love or farewell or recognition." The most profound symbolist we have: the joy and fun of Ulysses, he gave more to the prose than you could, he forced you to be more, to cross to where he was standing, seeing as only he could. Recommended reading: Exiles, Portrait of the Artist As A Young Man.

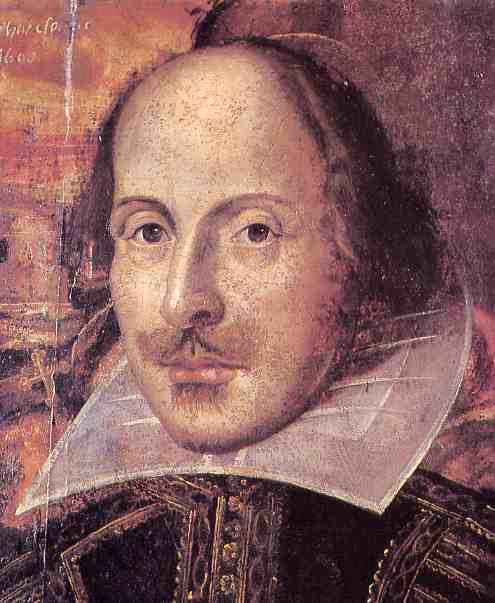

3. William Shakespeare

There's a lot to say about Bill. His mercy, his ways of thinking! He admired everything he gave voice to, we can also hope he admired himself. He took the old stories, and he wrote them new. Romeo and Juliet is just tremendous. Hamlet was better. Who could do comedy and tragedy with equal aplomb? He was master of satire, of broad and physical comedy. He was easy with stage directions, easy with criminals, harder on saints. Recommended reading: The Sonnets, King Lear, Othello, The Tempest, Twelfth Night, The Merchant of Venice.

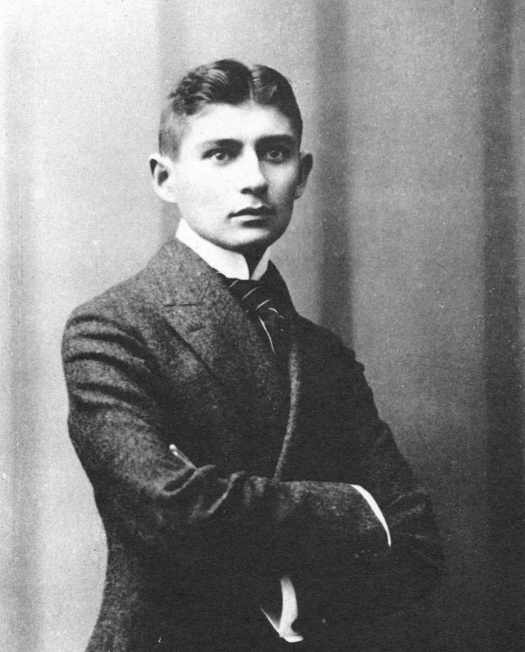

2. Franz Kafka

He was a genius, our brightest genius, our maker of myth and hater of self. Proof it can come from any place, even hate or fear. The Trial is forever his masterpiece. It can be read in any place, in any time, and it becomes about that place and time. It is man losing the primitive, acquiring a greater sense, changing into a monster, and growing no smarter about who he is or why he is there. All his novels are classics, even minor ones. His letter-writing! He is a code-maker, an analyst, a man of endless feeling, reserve, and talent. He wrote to God, addressed God, was God. As Whittaker Chambers put it about The Trial: "Beside that scene, against the cumulative background of that terrible story, most that has been written in our time about man's lot seems rather childlike. And beside Kafka's insatiable posing of the infinite question, most of his contemporaries' answers seem rather childish." Recommended reading: In The Penal Colony, The Castle, The Metamorphisis.

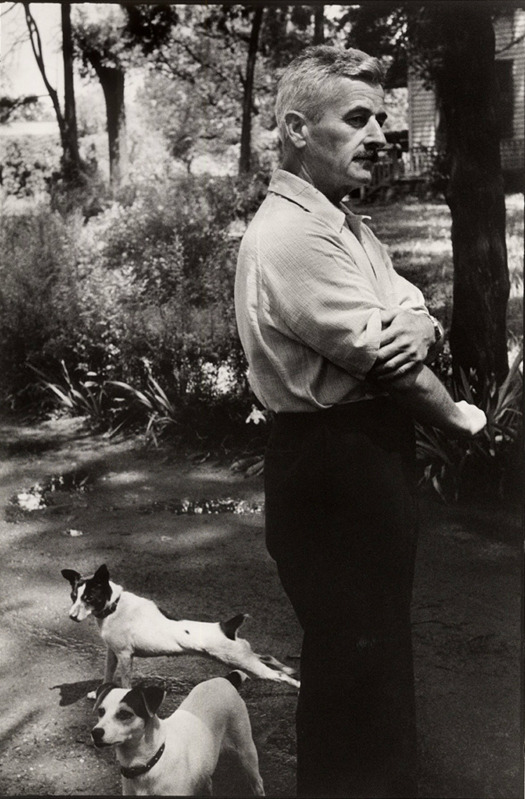

1. William Faulkner

Racism is not the greatest crime an author can commit, telling the truth is. Somehow Faulkner avoided both, achieving that glistening thing beyond truth, the local. Perhaps only Charles Olson, among the Americans, gives us as real a sense of place as Faulkner's apocryphal Yoknapatawpha County. The man could string together four, five adjectives and make it sound real. His command of syntactical structures pushed the language forward at least seventy-five years, which is to say nothing of his mesmerizing use of dialogue. There is a mindset in Faulkner that is at worst delusion and at best clairvoyance that sings the intricacies of capitalistic suffering deeper than naturalism and more fruitfully its accuracies than any mere realist. The personages in his books live not according to how he wrote them, but with a further life, unaccountable to genius or other machinations of ego. If we can keep anything, we take his lexicon, the words that lie at the interstisice of our wanting and our wanting to be. Our master, for all time.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. Will Hubbard is the executive editor of This Recording. Read the This Recording tumblr here. We appreciate your comments below.

BOOKS

BOOKS  Thursday, May 13, 2010 at 11:45AM

Thursday, May 13, 2010 at 11:45AM

max & franz Dear Max

max & franz Dear Max from steven soderbergh's 1991 movie

from steven soderbergh's 1991 movie

The Happy Ending of Franz Kafka's "Amerika" by Martin Kippenberger

The Happy Ending of Franz Kafka's "Amerika" by Martin Kippenberger w/ felice bauer March 17 1914

w/ felice bauer March 17 1914

berlin

berlin

diaries,

diaries,  franz kafka,

franz kafka,  max brod

max brod