BOOKS

BOOKS In Which James Schuyler Demands So Little Of Us

Wednesday, June 15, 2011 at 11:30AM

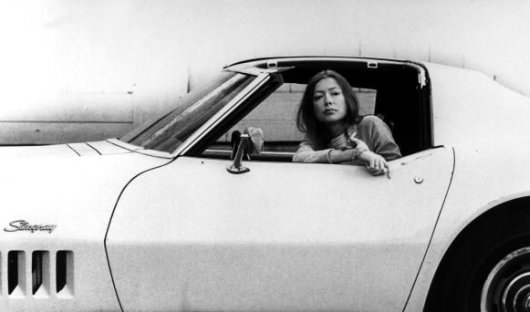

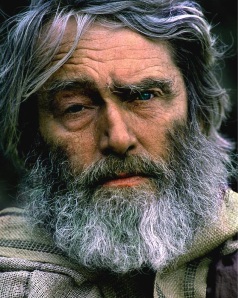

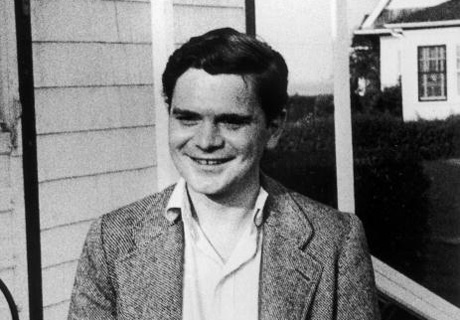

Wednesday, June 15, 2011 at 11:30AM  James Schuyler, Calais, Vermont, late 1960s; photograph by Joe Brainard

James Schuyler, Calais, Vermont, late 1960s; photograph by Joe Brainard

A Beautiful Intensity of Focus

James Schuyler overcame a horrifying childhood (he described it as out of "a novel by Dostoyevsky") to largely self educate himself, which was in stark contrast to the Harvard backgrounds of the other New York School poets. He was an accomplished writer of verse, a sometime novelist, and a constant art critic. His work populated Art News, his friends Fairfield Porter, Frank O'Hara and John Ashbery influenced each other's tastes.

Schuyler's letters are a treasure trove of insights from an incredibly sensitive man, and all his private writing (including his magical diary) stands alongside his superb poetry and prose despite his commentary to Anne Porter that "I do not regard personal letters as literature."

fairfield porter painting jane freilicher

fairfield porter painting jane freilicher

November 3, 1954

to JANE FREILICHER

Dear Jane,

It's raining. I hate what I've been writing. I've spent more money than I should, and wonder how I'll get through the weekend. I have a peculiar feeling in the ball of my right foot (sort of between a fish hook and a feather). An oh yes, Bill Weaver is coming by in a hour to take me to a cocktail party I don't want to go to, because I know the people are already offended with me for not having looked them up. And the electricity keeps going off. Otherwise I'm fine. How are you?

The boys are in England, after a big success in Belgium, and will be there next week. Arthur was very sick in Venice, with bronchitis — he's OK now, though really too broke down to be touring.

I meant my gloom to strike a lighter note than this — maybe it's because I went to see On the Waterfront last night, then read in bed Keats' last letters and all about his death. I bought myself some reading books, but it turns out the cheeriest one is a selected Matthew Arnold, who assures us in one verse that old age brings neither peace nor ease, just diminished powers, less sleep, and regret for the time when one at least imagined old age might be nice. Oi. What a camp that one is. A real lead shoe-nik.

But I like Rome, and so would you. Though that academy — what a bunch. They make an off-night forum at the artist's club sound like "Socrate."

I seem to be in more of a state of mind to receive a letter than to write one. What are you doing? Are you going to show this year? Does Grace continue on her fantastic course? Have any of our lads found (or for that matter, sought) gainful employment? Frank wrote me a very funny letter about an outing he took with you, Joe, John Ashbery and Hal Fondren. You emerged very well, and John was caught in characteristic poses.

Now I'll climb into my fancy Dan and go laught it up with what Bill calls some "really very chic people, and quite amusing." Help. Write.

Love,

Jimmy

Rome

July 7, 1956

to FAIRFIELD PORTER

Dear Fairfield,

After two beautiful days we had three wet cold ones. The temperature went below 60 and we were all delighted and worked hard. But today it's summer again, not warm or dry enough for the beach, but nice with a lot of Boudin clouds bumping around in the blue.

All our social life has consisted of having Larry for dinner last night, as thrillingly full of his favorite subjects, him, as ever. He and Howie have a show at the bookshop (a sign says Larry Rivers in huge letters and then in tiny letters, "and his guest Howard Kanovitz") and Larry's picture of Joseph with his socks on and his pants off had to be taken down by popular request.

In its place there is a notice that says, in effect, due to the smallness of some, others may see the shocker by asking (as Larry said, the only thing that shocks people in paintings nowadays is a "male penis"). He had also a letter from your dealer who hated Paris and loved London and says he is going to be very big for Jane next year because he has been to some museums and now gets what's she's after.

Larry had to leave early, unfortunately, because Stevie and a playmate had disappeared into Riverhead where there is a carnie show with a strip tease dancer and they still weren't home by 9:30. Guess they did make it safely back to their respective hysterical mother and grandmother or we would have heard.

Everything about the house is fine (not to say beautiful and a joy). Arthur Weinstein prowled through like a cat-detective and is already to line up a membership for you in the IDA (Interior Decorators Assoc.) My only complaint is that the stove demands so little of me.

The lilies by the barn opened yesterday in the rain, and first big daisy opened this morning. The new bed is full of beautiful delicate flowers. Although I only take my face out of the Flower encyclopedia long enough to put it in my dinner, I seem to know practically none of their names - there's sweet alyssum, and poppies, deep yellow ones and a scarlet one, but are they California, Iceland or Siberian poppies? And zinnias and bachelor buttons are in bud.

We had a charming card from Laurence, who says he likes the chaperoning job and will be here about July 27th for three or four nights. We'll be glad to see him (though it occurs to me now that I will probably be in town then reviewing). He has such elegant handwriting.

I writing in the studio (I sound like a Chinaman) - and of the pictures you left out I particularly love the one of Jerry that's given you so much trouble. It doesn't look unfinished or incomplete to me, it has a beautiful intensity of focus, first on the face, secondly on the dishes, with everything else "There" to just the degree that what's arund what one looks at is seen. And I love the living room, transparent as a water color and the snowy spring light.

I had a postcard from John Ashbery in which he says he guesses it's definite he'll be in France another year, though he will be here in September. I enclose the two poems he sent me I mentioned at Kenneth's. I'd like them back, and I'd like to see the ones he sent you, if you have them, and I'll return them.

Soon as I can pull myself together and wrap it, I'll send you a book I have for you. It's four poets, and I want to give it to you because I like Wyatt so much, and I think you might, too, and because the editor's introduction is interesting. He says some simple things about scanning five beat lines that seem to make a subject I've never much grasped a lot clearer. When I send it I'll mark the passage I mean.

When circulars come, and they do, shall we just put them in the basket by the front door?

Alvin N has decided that he and John shouldn't live together anymore, which is sad and stupid. It wouldn't surprise me though if he changed his mind later; I think in the end he is the one who would be worst off. Or benefit least, or something. Jane's comment was, "It proves again that man's inhumanity to man is equaled only by his inhumanity to himself."

The boys are going in next Tuesday to play on a TV show and will bring the lady la Rochefoucalud (sp?) back with them if she can prevail on Joe to drive out Friday for the weekend. I hope so. I'm dying to see her.

Kenneth said they were going to visit you in August. I think Great Spruce Head is the prefect place to contain him and set him off. And he can write his Katherine Kanoe Kantos.

Every second, today becomes more overpoweringly beautiful. I'd like to make an anthology of all the lines of poetry with the word blue in them, beginning with Frank's "It's the blue!" "...si blew, si calme..." "...in unending blueness...." (On the other hand I can't think of a drearier poem than the one of Herbert's that begins so marvelously about "Sweet day, so cool, so calm, so far..." (I think it is) and then points out that it won't last forever. I hate all those dusty-answer poems about how someone or something is as pretty as a peach but after a while it's going to be all awful looking. And I don't think it's Christianity that's to blame — though it might be Protestantism — Dante doesn't talk that way.)

I've been alternately reading Proust and the Divine Comedy. No comment.

And I read Measure for Measure again. When you read him, there is really no one but Shakespeare; the exhilaration, the invention, the clarity, the truth. I think I really like the late comedies the most, Measure for Measure, The Winter's Tale, and The Tempest. Though my special love is As You Like It, it's so artificial, it doesn't make the faintest pretense that its existence was obliged, was called for.

Bigger works of art always seem to threaten to help one in some way or another, and therefore the fact they exist is part of the Social Good. As You Like It is just there, like the one red popppy across the lawn, pure excess of delight.

Speaking of pure excess, I've been on a diet. A few weeks ago I weighed 171, now I weight 163, and I'm not going to think about stopping until I find out how I look and feel at 155. In fact we are all on diets, and since we've been here have broken down only once, when we stormed up Main Street at 10:30 one night and had hot fudge and butterscotch sundaes. Of course we talk about nothing but food — even to the exclusion of Europe, our one other subject - and Bobby and I read antiphonally from Sheila Hibben and Tante Marie's Pastry book to an accompaniement of moans. It does seem absurd that when we open that marvelous oven great cinnamon smelling gusts don't come pouring out.

My love to Anne and Katy and Elizabeth. Were you able to get someone to help with the house work?

I hope I'll hear from you soon.

Love,

Jimmy

Southampton

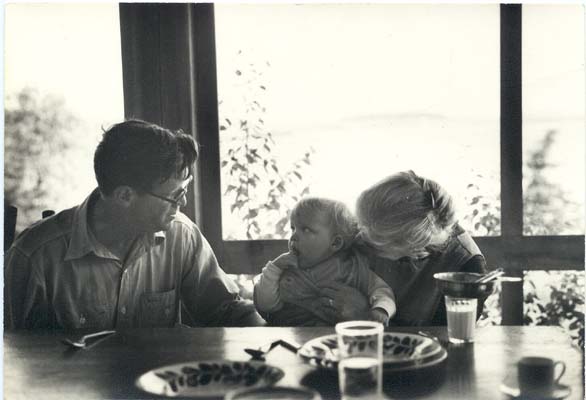

schuyler's photograph of fairfield porter

schuyler's photograph of fairfield porter

Thursday Fall 1955

to FAIRFIELD PORTER

Dear Fairfield,

How delightful to find your handwriting in an anonymously addressed envelope, when I dismally thought all the mail was another throw-away. I shall go right away to see Calcagno, and Feeley too.

But how inaccurate of you to have told Frank and Kenneth that the reason you didn't call me is that it is you who always call! Wasn't it I who called you in Southampton when I heard you were back and coming into town? And I who called you the day we were moving, when you and I went downtown and you bought the beautiful white lamp that has given us so much pleasure and illumination? And often when it has been you who called, wasn't it because we had arranged it so beforehand — as often at my suggestion as yours — on the ground that you would be out during the day, and I would be in?

I did try to call you the week of John's party, and then gave it up because I was aware of the deliberateness in your silence. One's often tempted to test one's friends in these little ways — at least I am — but it's my experience that to do so is a challenge to the friend to show that he has the nerve and heartlessness to fail one; and most of us have.

Besides, I think you exaggerate the degree of initiative you take in your friendships: I know, because I'm shy, that it often takes more initiative for me to bring myself to say yes to an invitation than it took for the inviter to issue it.

While I'm at it, I'm also rather put out by this youth and age stuff. In so far as I think of you as "older," I feel honored and benefited by your friendship; but if it turns out that you feel odd in bestowing it, I feel snubbed. I don't, though, think of you as "older" so much as I do a friend who has had a life very different from mine (but if I must think about it, then I say that I think I'm a man over thirty, past which age one might hope to have gained the right to mingle with one's elders &/or betters).

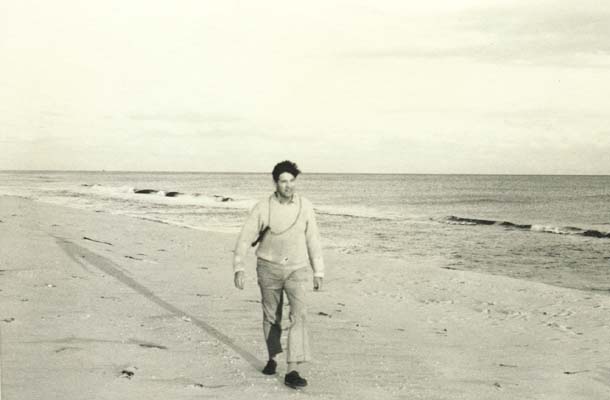

watching tv with the gang in 1955

watching tv with the gang in 1955

I wish I thought you dwelt a little on the virtues of your behavior: and saw that if (as I hope you do) you take pleasure in the company of Frank and Jane and Kenneth and Barbara and the rest of us, it's because your mind hasn't sealed over, that you've kept a fresh enthusiasm and curiosity, a desire to catch the contagion from your creative people and at the same time to help and instruct: equally admirable. How grateful John Button is to you for the things you said to him about his painting, and who else is there who could say them?

Someone else might OK his pictures - but that's just approval; someone his own age might criticize them in a helpful way, but that would lack the validity of experience. I cannot, literally bring to mind anyone else who would and could do it. Tom Hess wouldn't; Alfred Barr is too diplomatic; Larry would be jealous; John Myers is a dope...and so on. (I thought his paintings beautiful, and praised them as best I could; but I certainly have no painting pointers to give him!)

All I mean is that it seems to me merely another instance of American self-consciousness when confronted by one's oddness, when the oddness is what makes value. Do you think your paintings would keep gaining in quality — as I think they do — if you had been one of those dreary artists who hunt for it in their twenties, find it in their thirties and then do it for the rest of their lives? Oh the acres of Kuniyoshi and Reginald Marsh: I don't say their work was without merit, but I think it's mostly an achieved manner, and manner, en masse, makes for ennui. I wish instead of odd, you thought yourself as unique; you seem so to me, in relation to your brothers and sister, to other artists, to other men your age, to other members of the class of '28 (if that is the right year) — but then, they haven't had a long draught from the only spring that matters. You have.

I hope this doesn't seem impudent and fresh; which was no part of my plan.

Frank is not going to review anymore, and Betty Chamberlin called and asked if I'd write three sample reviews; so I shall, over the weekend. I wish you were going to be here to criticize them for me, but I shall do it the best I can and keep copies to show you.

I hope soon I can come out and visit you; since you said at Morris I knew "damn well I could." Pretty strong talk, pardner.

I'm enjoying enormously working over my book with Catherine Carver. I think it will turn out one that I will like much more than the one I submitted. It seems as thought every place where she puts her finger is one I had at some time thought myself might be a little pulpy or squashy.

I'll write more chattily another time, when you tell me that you've forgiven me for anything in this letter than needs forgiving. None of it means anything serious, in light of the joy it gave me to see your face light up when you finally saw me signaling wildly from that moving cab.

My love to Anne and Kitty and yourself. I long to hear news of Jerry.

As always,

Jimmy

P.S. Would you call me next Tuesday? I expect to be in all day.

ashbery, koch, jane freilicher, nell blaine among others

ashbery, koch, jane freilicher, nell blaine among others

Spring 1956

to JOHN BUTTON

Dear John,

I don't know why I have to tell you this today (but I do) — perhaps it's because when I look out into the fog all I can see is the hairs of your adorable chest. I'm terribly in love with you, and have been for such a long time, ever since the first time Frank took me to your apartment. I looked around at your beautiful paintings and suddenly everything I'd ever felt about you turned into a diamond or a rose or something — anyway I went striding up and down while Frank played Poulenc and felt exactly like the Ugly Duckling the day he found he was a swan.

Then you came home and I didn't think I could ever look at you or to you again, all I could do was giggle and snort and twitch. But I've looked at you a lot since then, and there isn't anybody else in the world I want to look at; or want, for that matter.

It seems to me that I've been so GOOD that I couldn't hate myself more. I don't see why I couldn't have been born a robber baron type instead of a fool.

Now I'm going down and set 57th Street on fire to keep you warm.

This is all nonsense. I love being in love with you, it makes even unhappiness seem no bigger than a pin, even at the times when I wish so violently that I could give my heart to science and be rid of it.

with all my love,

Jimmy

Please don't tell Alvin, I don't think I could bear to meet him if I thought he knew.

The publisher and editor Donald Allen asked Schuyler for advice about an anthology he was putting together.

September 20, 1959

to DONALD ALLEN

Dear Don:

Here, from the welter of papers I've been carrying about, are a few poems; and a copy of the play that amused Frank, and (of "historical" interest), an imaginary conversation, written after seeing Frank's first book and walking up Park Avenue with him one May evening. I may send you a few more, but there aren't any I like better than "February," "The Elizabethans Called It Dying," and "Freely Expousing."

I was so interested in what Frank told me about his talk with you last Sunday. Olson may well be right, and there is a real point to putting in "background" or older poets. But if you want to represent the influence of readers as systematically omnivorous as Frank, John A, Prof. Koch and, me too, well: wow. Frank sometimes tends to cast the splendid shadow of his own sensibility over the past, as well as his friends, and while a brush of his wings is delightful, it is also somewhat heady. I thought you might be interested in what I remember people as actually reading.

John Wheelwright: particularly the poems in Rock and Shell.

Auden: like the common cold. Frank and Kenneth still profess; I grudgingly assent (though if Auden doesn't drop that word numinous pretty soon, I shall squawk).

For the greats: Williams, Moore, Stevens, Pound, Eliot. I doubt if any very direct connection can be found between Moore and anymore. I wanted to write like her, but her form is too evolved, personal and limiting. After a bout of syllable counting, to pick up D.H. Lawrence is delightful.

Eliot made the rules everybody wants to break.

Stevens and Williams both inspire greater freedom than the others, Stevens of the imagination, Williams of subject and style.

Pound I wonder about. Like Gertrude Stein, he is an inspiring idea. But a somewhat remote one. A poem like Frank's Second Avenue might seem influenced by the Cantos, but Breton is much closer to the mark.

Continental European literature is, really, the big influence: the Greats, plus Auden, seemed to fill the scene too completely - so one had to react with or against them, casting off obvious influences as best one can. In the context of American writing, poets like Jacob and Breton spelled freedom rather than surreal introversion. What people translate for their own pleasure is a clue: Frank, Holderlin and Reverdy, John Ashbery (before he'd been to France, Jacob's prose poems; Kenneth and I have both had a go at Dante's untranslatable sonnet to Cavalcanti; I've translated Dante, Leopardi and fruitlessly, Apollinaire and Supervielle (I like the latter's stories better than his poems.) But Pasternak has meant more to us than any American poet. Even in monstrous translations his lyrics make the hair on the back of one's neck curl.

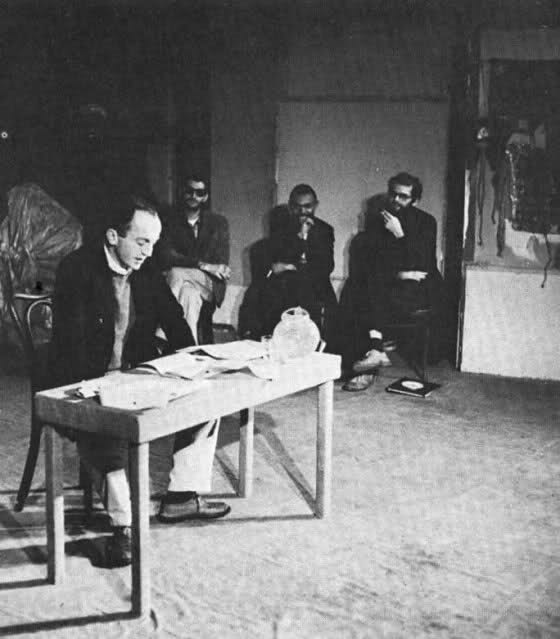

Patsy Southgate, Bill Berkson, John Ashbery; seated, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch. Frank O’Hara’s loft, 1964

Patsy Southgate, Bill Berkson, John Ashbery; seated, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch. Frank O’Hara’s loft, 1964

But back to Americans. The horrid appearance of the sestina in our midst (K. and Fairfield Porter used to correspond in sestinas) can be traced directly, by way of John Ashbery's passion for it, to one by Elizabeth Bishop. Its title eludes me: one of the end words is coffee, and it is in her first book.

Hart Crane: very much, and perhaps for extra-poetical reasons that aren't so extra. But he has exactly what's missing in "the poetry should be written as carefully as prose" poets: sensibility and heart. Not "The Bridge," of course (not yet anyway) - I think it's impossible for anyone not to premise so overtly an "American" idea. I don't mean that I don't enjoy the poem; but there is, at bottom, a rather hick idea of America challenging Europe, when Whitman had already conquered with a kiss. But do look at "Havana Rose" in the uncollected poems, or "Moment Fugue" (I'd give the tooth of an owl to have written that) or a song like "Pastoral":

No more violets

And the year

Broken into smoky panels

What a beginning.

John and Frank not now, and Kenneth perhaps, admire or admired Laura Riding, but she won't let her poems be reprinted. I have always found them rather arid going, myself.

On reflection: I don't think I'm right about Gertrude Stein. Certainly the Becks production of Ladies Voices (on the same bill as Picasso's Desire Caught by the Tail, in which Frank and John A. appeared as a couple of dogs, night after night) in 1952 influenced me immediately and directly. To represent her by a work like Ladies Voices would be truer than to include almost anything of Eliot's.

I like Eliot but what Parson Weems was to other generations The Waste Land was to us; Pablum.

Also, in tracing influences — the important ones — there is this: that while John Wieners by chance first got word from Olson at a Boston reading (then later went to Black Mountain College) and put it to good use, it is experience unlike that of any other talented poet I know. Frank studied with Ciardi, but if another writer had been giving the course, Frank would have taken it. (Olson's own allegiance to Pound-Fenellosa can't be generalized for others - unless you have room for all of Proust, The Golden Bowl, Don Juan (very operative on Frank and Kenneth) and Lady Murasaki. All through high school one of my sacred books was Mark Van Doren's Anthology of World Poetry. (In which I first read poems by Thoreau; I'm not all that international.)

I was so delighted to hear that you asked Frank about Edwin Denby's poems; I hope you have seen Mediterranean Cities as well as the earlier book. His harsh prosody I find a relief.

There is a poet who died whose name escapes me: Frank and John admire his work very much, and I think Frank has copies of the QRL with poems of his. Perhaps Frank has already mentioned him to you.

I trust we'll talk soon. I didn't mean to go on at this length, but if you can find anything for your anthology in these maunderings, so much the better.

Yours,

Jimmy

New York

July 28, 1966

to JOHN ASHBERY

Dear John,

I still feel stunned by Frank's death. If you feel equal to it, I would like to know a little more than is in today's Times, who was he staying with? Or anything you think I might want to know. But if you would rather not write about it, don't.

I finished copying the enclosed. Please go over it carefully for spelling, pointing, accents, and anything else. If you want to change or add anything, do so. Camellia does have two ll's and Sally Lunn is singular - anything else that looks like a mistake is a mistake.

It was like a dream come true to have you here, and unfortunately as quickly passed. Joe writes that "you got some dishes' - what are they like? Also, how long does the bus trip from Vermont (Burlington?) take?

I'll send the parts of what we wrote here that you don't have soon.

I'm sorry my typewriter and I are such bum copyists.

Let me hear from you soon. My love to M.

love,

Jimmy

Great Spruce Head

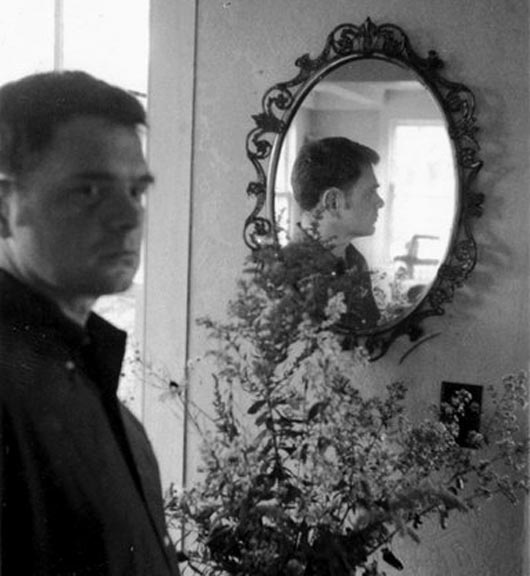

with frank o'hara in 1956

with frank o'hara in 1956

The balustrade along my balcony

is wrought iron in shapes of

flowers: chrysanthemums, perhaps,

whorly blooms and leaves and

along the top a row of what look

like croquet hoops topped by a

rod, and from the hoops depend

water drops, crystal, quivering.

Why, it must be raining, in Chelsea,

NYC!

James Schuyler died of a stroke in 1991. You can find his reminiscence of Frank O'Hara here. You can find more reminiscences of Frank O'Hara here. This is the second in a series. You can find the first part here.

For me Jimmy is the Vuillard of us, he withholds his secret, the secret thing until the moment appears to reveal it. We wait and wait for the name of a flower while we praise the careful cultivation. We wait for someone to speak. And it is Jimmy in an aside.

— Barbara Guest

The Best of Donald Allen's Poets

Kyle Schlesinger on Charles Olson

The autobiography of Robert Creeley

John Ashbery on the paintings of Fairfield Porter

Bridget Moloney's introduction to Frank O'Hara

Ed Dorn remembers Richard Brautigan

Alex Carnevale profiles Fairfield Porter

John Ashbery's conversation with Kenneth Koch

James Schuyler's essay about Frank

Jane Freilicher, as seen by John Ashbery

The letters of Bob Creeley and Charles Olson

Will Hubbard on the poetry of John Ashbery

After Frank's death, these poets eulogize him