BOOKS

BOOKS In Which When It's Cold James Schuyler Would Like To Cry

Friday, September 2, 2016 at 11:48AM

Friday, September 2, 2016 at 11:48AM

The Plans of James Schuyler

For me Jimmy is the Vuillard of us, he withholds his secret, the secret thing until the moment appears to reveal it. We wait and wait for the name of a flower while we praise the careful cultivation. We wait for someone to speak. And it is Jimmy in an aside.

— Barbara Guest

James Schuyler was a sailor in the Navy until he got too drunk during a leave in New York and didn't show up the next day. He was discharged from the Navy shortly thereafter because of that and his evident homosexuality, and his life as a writer in New York began. Schuyler overcame a horrifying childhood (he described it as out of "a novel by Dostoyevsky") to largely self educate himself, which was in stark contrast to the Harvard background of most of the New York poets.

Schuyler was an accomplished poet, a sometime novelist, and a constant art critic. The work of he and his peers populated Art News; his friends Fairfield Porter, Frank O'Hara and John Ashbery influenced each other's tastes and appreciation. His letters are a treasure trove of insights from an incredibly sensitive man, and all his private writing (including his magical diary) stands alongside his superb poetry and prose despite his commentary to Anne Porter that "I do not regard personal letters as literature."

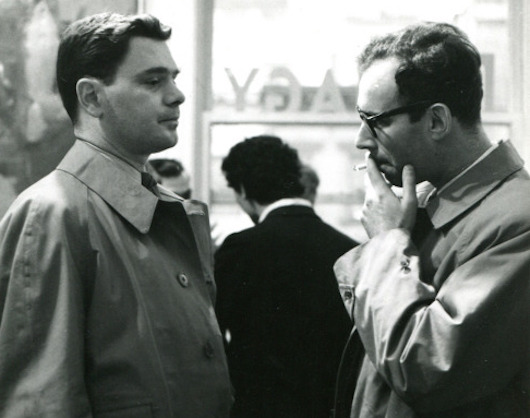

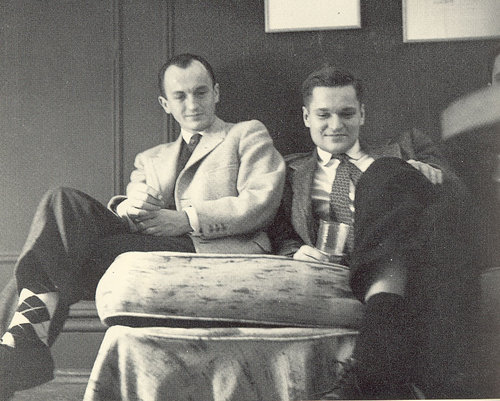

with frank o'hara in 1956

with frank o'hara in 1956

November 3, 1954

to JANE FREILICHER

Dear Jane,

It's raining. I hate what I've been writing. I've spent more money than I should, and wonder how I'll get through the weekend. I have a peculiar feeling in the ball of my right foot (sort of between a fish hook and a feather). An oh yes, Bill Weaver is coming by in a hour to take me to a cocktail party I don't want to go to, because I know the people are already offended with me for not having looked them up. And the electricity keeps going off. Otherwise I'm fine. How are you?

The boys are in England, after a big success in Belgium, and will be there next week. Arthur was very sick in Venice, with bronchitis — he's OK now, though really too broke down to be touring.

I meant my gloom to strike a lighter note than this — maybe it's because I went to see On the Waterfront last night, then read in bed Keats' last letters and all about his death. I bought myself some reading books, but it turns out the cheeriest one is a selected Matthew Arnold, who assures us in one verse that old age brings neither peace nor ease, just diminished powers, less sleep, and regret for the time when one at least imagined old age might be nice. Oi. What a camp that one is. A real lead shoe-nik.

But I like Rome, and so would you. Though that academy — what a bunch. They make an off-night forum at the artist's club sound like "Socrate."

I seem to be in more of a state of mind to receive a letter than to write one. What are you doing? Are you going to show this year? Does Grace continue on her fantastic course? Have any of our lads found (or for that matter, sought) gainful employment? Frank wrote me a very funny letter about an outing he took with you, Joe, John Ashbery and Hal Fondren. You emerged very well, and John was caught in characteristic poses.

Now I'll climb into my fancy Dan and go laught it up with what Bill calls some "really very chic people, and quite amusing." Help. Write.

Love,

Jimmy

Rome

August 15, 1955

to KENNETH KOCH

Dear Ken,

A stay in Penobscot Bay has turned my typewriter into a rusty heap. The fogs they have there, you see. I also saw all the Porters, for a month. I loved it there and hate here, where I've just put Frank in a cab and pointed him toward the airport, as he's going to Great Spruce Head to replace me.

I loved your letters.

I'm glad you're all coming home. I'm not sure thought it's fair to rob Baby Kathy of a good grounding in French. Perhaps she should stay. She could support herself modeling baby clothes in the plastic napkin ring boutique at Balenciaga.

But you're not bringing Mercedes? I was dying to meet her. I like anyone connected with The Paris Review.

Harcourt, Brace has my novel (called Alfred & Guinevere - no crax pliz). They have had it for a month. They are waiting for a parade to come by so they can throw it out the window. But now the sweaty but smiling Irish policemen are diverting traffic, for a parade is coming. Yes, a parade! Swee the swirling Kelly green and white sateen skirt of the sweaty but smiling little drum majorette. How brave she is, right out there in front of all the drum and bugle corps of St. Ignatius Loyola High. For it is March, and many months have passed since Jimmy's little novel went far, far away to the where only the cry of the loon and the chittering of the spruce needles on the frozen snow troubles Great Jibjib's rest...

New York is hot and tiresome. But I wouldn't want to live in Boston.

Or Buffalo.

Jane is learning a trade. It's some kind of electrified typewriting and super-shorthand. I guess it depresses her, but she will be able to make pots and pots of money and go far, far away from her chalks and plasticene.

Frank has written one play, one short story, ten or more poems. I have read some of the poems but not the play or short story. He also has a new friend he likes very much, a poet named Edward Field who has been published in Botteghe Oscure. He seems sweet and good, qualities I never found it in my heart to attribute to Larry Rivers.

John [Ashbery] is going home to Sodus next week. Then he will come back on Sept. 18 before he goes to France. Morris Golde is going to give a drunken rout for him I know Baby Cathy will not want to miss.

Arthur and Bobby are recording all the two piano and four hand music of Mozart. It is a lot of work, but the works are very, very beautiful.

In Maine Anne used to say every morning, "I must write Janice and invite Kenneth and Janice and the baby to come and stay with us for weeks and weeks."

I started another novel there. But I don't like it, no, not a bit. I will start another one!

Fairfield painted many pictures. He painted a picture of me! In a yellow shirt.

Did John Myers sent you the ; with my little old play, Love Before Breakfast, in it?

Will this reach you before the stork brings you all home in a napkin?

If I can find it, I will enclose the "Think & Grin" page from Boy's Life, the July issue. I tore it out for you anyway, but I am a great mis-placer.

It will be good to see you when you are far, far away from France.

Love to Janice, love to Baby, love.

Jimmy

Thursday Fall 1955

to FAIRFIELD PORTER

Dear Fairfield,

How delightful to find your handwriting in an anonymously addressed envelope, when I dismally thought all the mail was another throw-away. I shall go right away to see Calcagno, and Feeley too.

But how inaccurate of you to have told Frank and Kenneth that the reason you didn't call me is that it is you who always call! Wasn't it I who called you in Southampton when I heard you were back and coming into town? And I who called you the day we were moving, when you and I went downtown and you bought the beautiful white lamp that has given us so much pleasure and illumination? And often when it has been you who called, wasn't it because we had arranged it so beforehand — as often at my suggestion as yours — on the ground that you would be out during the day, and I would be in?

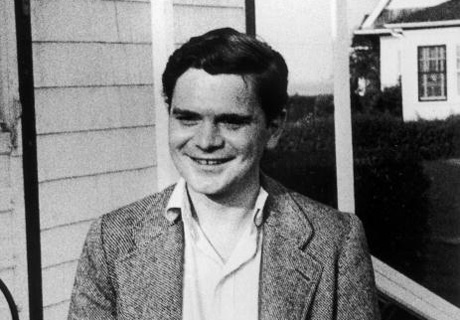

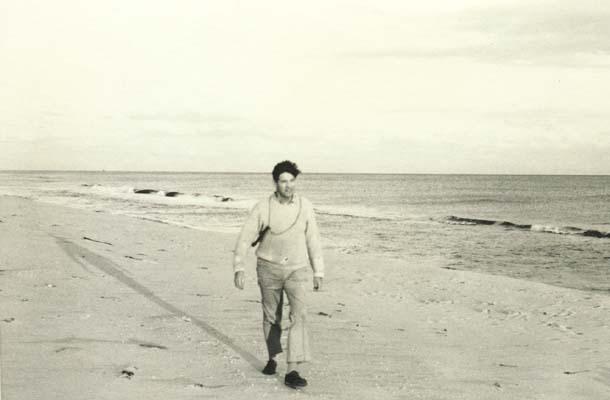

schuyler's photograph of fairfield porter

schuyler's photograph of fairfield porter

I did try to call you the week of John's party, and then gave it up because I was aware of the deliberateness in your silence. One's often tempted to test one's friends in these little ways — at least I am — but it's my experience that to do so is a challenge to the friend to show that he has the nerve and heartlessness to fail one; and most of us have.

Besides, I think you exaggerate the degree of initiative you take in your friendships: I know, because I'm shy, that it often takes more initiative for me to bring myself to say yes to an invitation than it took for the inviter to issue it.

While I'm at it, I'm also rather put out by this youth and age stuff. In so far as I think of you as "older," I feel honored and benefited by your friendship; but if it turns out that you feel odd in bestowing it, I feel snubbed. I don't, though, think of you as "older" so much as I do a friend who has had a life very different from mine (but if I must think about it, then I say that I think I'm a man over thirty, past which age one might hope to have gained the right to mingle with one's elders &/or betters).

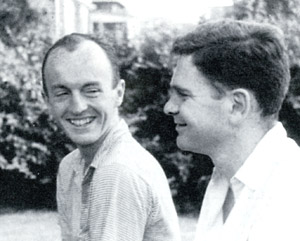

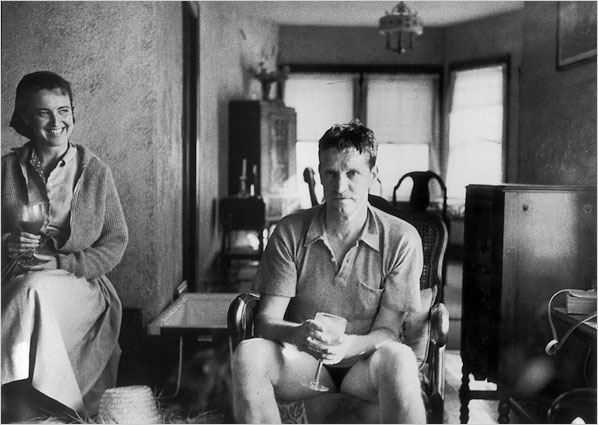

watching tv with the gang in 1955

watching tv with the gang in 1955

I wish I thought you dwelt a little on the virtues of your behavior: and saw that if (as I hope you do) you take pleasure in the company of Frank and Jane and Kenneth and Barbara and the rest of us, it's because your mind hasn't sealed over, that you've kept a fresh enthusiasm and curiosity, a desire to catch the contagion from your creative people and at the same time to help and instruct: equally admirable. How grateful John Button is to you for the things you said to him about his painting, and who else is there who could say them?

Someone else might OK his pictures - but that's just approval; someone his own age might criticize them in a helpful way, but that would lack the validity of experience. I cannot, literally bring to mind anyone else who would and could do it. Tom Hess wouldn't; Alfred Barr is too diplomatic; Larry would be jealous; John Myers is a dope...and so on. (I thought his paintings beautiful, and praised them as best I could; but I certainly have no painting pointers to give him!)

All I mean is that it seems to me merely another instance of American self-consciousness when confronted by one's oddness, when the oddness is what makes value. Do you think your paintings would keep gaining in quality — as I think they do — if you had been one of those dreary artists who hunt for it in their twenties, find it in their thirties and then do it for the rest of their lives? Oh the acres of Kuniyoshi and Reginald Marsh: I don't say their work was without merit, but I think it's mostly an achieved manner, and manner, en masse, makes for ennui. I wish instead of odd, you thought yourself as unique; you seem so to me, in relation to your brothers and sister, to other artists, to other men your age, to other members of the class of '28 (if that is the right year) — but then, they haven't had a long draught from the only spring that matters. You have.

I hope this doesn't seem impudent and fresh; which was no part of my plan.

Frank is not going to review anymore, and Betty Chamberlin called and asked if I'd write three sample reviews; so I shall, over the weekend. I wish you were going to be here to criticize them for me, but I shall do it the best I can and keep copies to show you.

I hope soon I can come out and visit you; since you said at Morris I knew "damn well I could." Pretty strong talk, pardner.

I'm enjoying enormously working over my book with Catherine Carver. I think it will turn out one that I will like much more than the one I submitted. It seems as thought every place where she puts her finger is one I had at some time thought myself might be a little pulpy or squashy.

I'll write more chattily another time, when you tell me that you've forgiven me for anything in this letter than needs forgiving. None of it means anything serious, in light of the joy it gave me to see your face light up when you finally saw me signaling wildly from that moving cab.

My love to Anne and Kitty and yourself. I long to hear news of Jerry.

As always,

Jimmy

P.S. Would you call me next Tuesday? I expect to be in all day.

Spring 1956

to JOHN BUTTON

Dear John,

I don't know why I have to tell you this today (but I do) — perhaps it's because when I look out into the fog all I can see is the hairs of your adorable chest. I'm terribly in love with you, and have been for such a long time, ever since the first time Frank took me to your apartment. I looked around at your beautiful paintings and suddenly everything I'd ever felt about you turned into a diamond or a rose or something — anyway I went striding up and down while Frank played Poulenc and felt exactly like the Ugly Duckling the day he found he was a swan.

Then you came home and I didn't think I could ever look at you or to you again, all I could do was giggle and snort and twitch. But I've looked at you a lot since then, and there isn't anybody else in the world I want to look at; or want, for that matter.

It seems to me that I've been so GOOD that I couldn't hate myself more. I don't see why I couldn't have been born a robber baron type instead of a fool.

Now I'm going down and set 57th Street on fire to keep you warm.

This is all nonsense. I love being in love with you, it makes even unhappiness seem no bigger than a pin, even at the times when I wish so violently that I could give my heart to science and be rid of it.

with all my love,

Jimmy

Please don't tell Alvin, I don't think I could bear to meet him if I thought he knew.

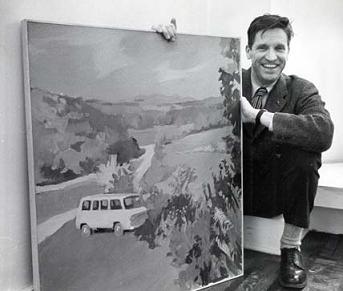

Patsy Southgate, Bill Berkson, John Ashbery; seated, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch. Frank O’Hara’s loft, 1964

Patsy Southgate, Bill Berkson, John Ashbery; seated, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch. Frank O’Hara’s loft, 1964

Schuyler wrote the following letter from Grace New Haven Hospital. At 37, Schuyler had resigned from his position at the MoMA and entered treatment the following month after a nervous breakdown. He never had a day job again.

May 15, 1961

to JOHN ASHBERY

Dear John,

Well, dear boy, here I am — in the rather advanced psychiatric clinic run by Jimmy Merrill's ex-analyst (which may explain how I came to afford $300 a week for mental hygiene). I had a vile winter, but now I feel over the hump — Today I was out of doors for the first time since March. Joy — the bliss of a warm sun and a cool breeze off the pizza parlors!

I was terribly impressed by Locus Solus. Harry seems to have all the qualities of a self-interested saint.

By the way, I did look for that tax check - your checks are all filed in an orderly way, & I did not find it.

My news is zero — let's see. Yesterday I bid & made a slam (yawn) —

So the burden of writing cheery notes (long notes) is on you, now that I've regained use of my letter writing head.

Do you and Pierre continue, after your fashion? I always hope so.

Fairfield proposed me for The Nation art critic, but Lincoln Kirstein bids for R. Rosenblum. Grr; even if I haven't met him.

Time for 8 p.m. milk & cookies -

Love to P.

Love,

Jimmy

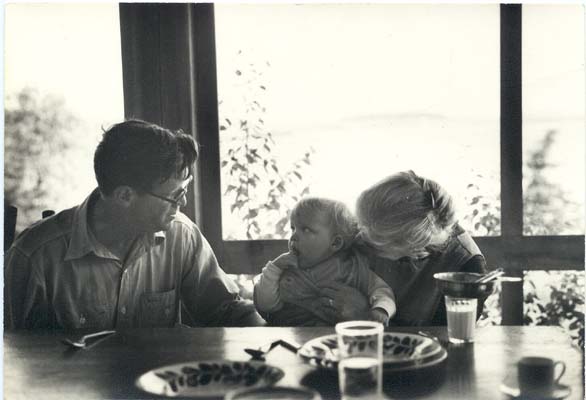

fairfield porter & jane freilicher

fairfield porter & jane freilicher

Jan. 9, 1962

to FAIRFIELD PORTER

Dear Fairfield,

I knew I had written a poem in the hospital, and that it wasn't a bad one, but I could never find it. Of course it's about the small painting you gave me when I went to New Haven. Now, much later than I meant to, here is a present of a poem about it.

You may be sure John Ashbery is my best friend; I'm not.

I borrowed twenty dollars from Wystan Auden in my loss-hysteria. Art News has GOT to pay me!

Please show the poem to Anne and ask her if she likes it.

I miss you.

Love,

Jimmy

A Blue Shadow Painting

for Fairfield Porter

of an evening real as paint on canvas

The kind that makes me ache to have the gift

for dusting off clichés:

not, make it new, but see it, hear it freshly.

The context (good morrow, haven't we met in this context before?)

in which, squelch, a brush lifted a load

of pigment from the thick glass palette, and, concentrated,

as though he saw neither the work in hand nor the subject,

The painter began. A rapt away look, like a woman at the theater,

who sorts laundry, makes a mental note while the stars anguish

to buy a bottle of Scuff-Coat tomorrow at Bohacks.

The painting portrays a sloppy evening in a burst of daily joy:

orange flames at left - were they bushes? - a gray-black tree,

at right, a few houses, buildings, no more than, well,

two gray strokes together, casual as a scribbled note, make a slate

roofed tower. Then there's one place where the light pink came to rest

under a faded butter-cup sky.

It's like this: the orange assertions, dark thereness

of the tree, malleable steel gray blueness of the ground; and sky;

set against, no, with, living with, existing alongside and part of,

the helter skelter of rust brown, of swift indecipherable. the day

is passing, is past: mutable and immutables, came to live

on a small oblong of stretched canvas. Blue shadowed day,

under a milk of flowers sky, you're a talisman, my Calais.

James Schuyler

Grace-New Haven Hospital

April 8, 1961

James Schuyler died of a stroke in 1991. You can find his reminiscence of Frank O'Hara here. You can find more reminiscences of Frank O'Hara here.

James Schuyler,

James Schuyler,  John Ashbery

John Ashbery