BOOKS

BOOKS In Which Our Upstairs Neighbor Is A Major Painter

Thursday, October 29, 2009 at 10:33AM

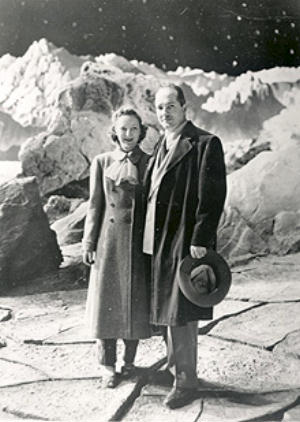

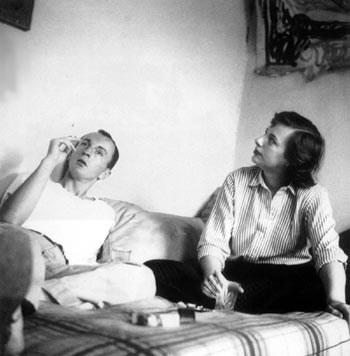

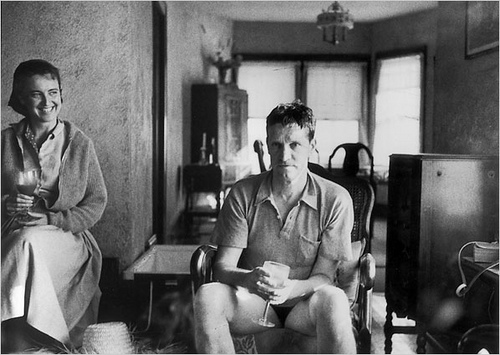

Thursday, October 29, 2009 at 10:33AM  with fairfield porterJane Freilicher

with fairfield porterJane Freilicher

by JOHN ASHBERY

I first met Jane Freilicher one afternoon in the early summer of 1949.

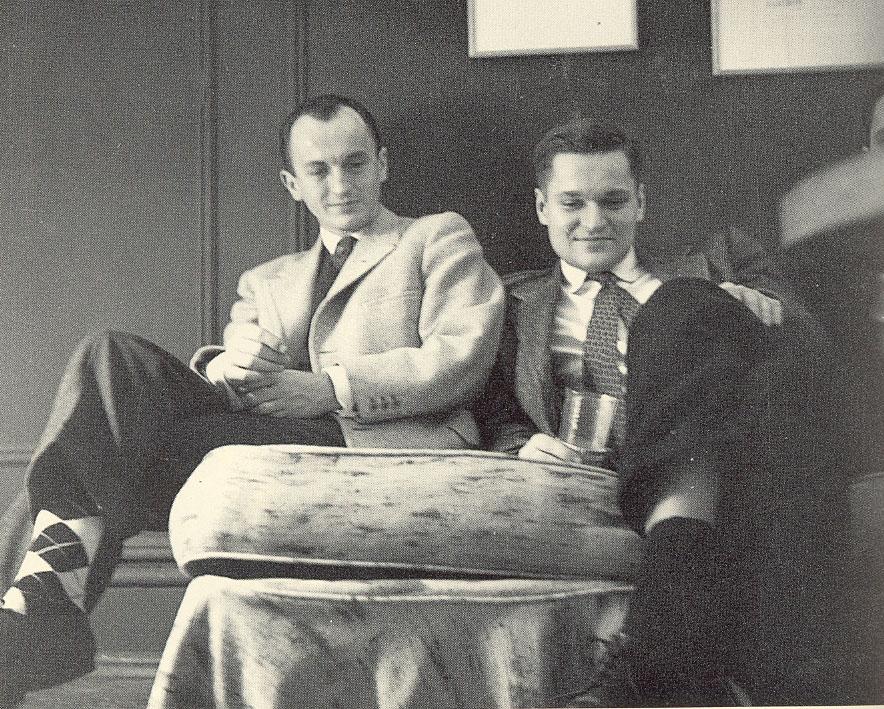

james schuyler, ashbery and kochI had recently graduated from Harvard and had somewhat reluctantly decided to move to New York, having been simultaneously rejected by the graduate school of English at Harvard and accepted at Columbia. Kenneth Koch, who had graduated the year before me, had been urging me to come and live in New York. He was at the time visiting his parents in Cincinnati, and told me I could stay in his loft (loft?) till he got back; his upstairs neighbor Jane would give me the keys. Accordingly I found myself ringing the bell of an unprepossessing three story building on Third Avenue at Sixteenth Street. Overhead the El went crashing by; I later found that one of Kenneth's distractions was to don a rubber gorilla mask and gaze out his window at the passing trains.

james schuyler, ashbery and kochI had recently graduated from Harvard and had somewhat reluctantly decided to move to New York, having been simultaneously rejected by the graduate school of English at Harvard and accepted at Columbia. Kenneth Koch, who had graduated the year before me, had been urging me to come and live in New York. He was at the time visiting his parents in Cincinnati, and told me I could stay in his loft (loft?) till he got back; his upstairs neighbor Jane would give me the keys. Accordingly I found myself ringing the bell of an unprepossessing three story building on Third Avenue at Sixteenth Street. Overhead the El went crashing by; I later found that one of Kenneth's distractions was to don a rubber gorilla mask and gaze out his window at the passing trains.

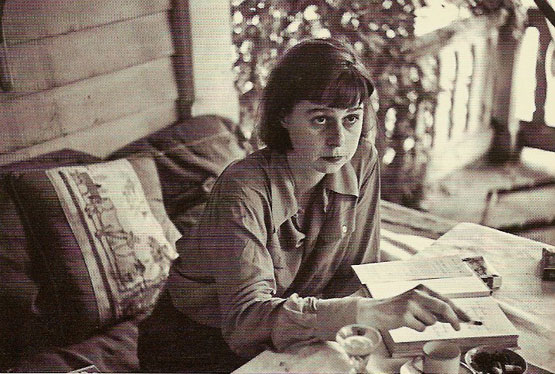

After a considerable length of time the door was opened by a pretty and somewhat preoccupied dark haired girl, who showed me to Kenneth's quarters on the second floor. I remembered that Kenneth had said that Jane was the wittiest person he had ever met, and found this odd; she seemed too serious to be clever, though of course on needn't preclude the other. I don't remember anything else about our first meeting; perhaps it was that same day or a few days later that Jane invited me in to her apartment on the floor above and I noticed a few small paintings around. "Noticed" is perhaps too strong a word; I was only marginally aware of them, though I found that they did stick in my memory.

As I recall, they were landscapes with occasional figures in them; their mood was slightly Expressionist, though there were areas filled with somewhat arbitrary geometrical patterns. Probably she told me she had done them while studying with Hans Hofmann, but it wouldn't have mattered since I hadn't heard of him or any other member of the New York School at that time. My course in twentieth-century art at Harvard had stopped with Max Ernst. (For academic purposes it was OK to be a Surrealist as long as the period of Surrealism could be seen as being in the past, and things haven't changed much since.)

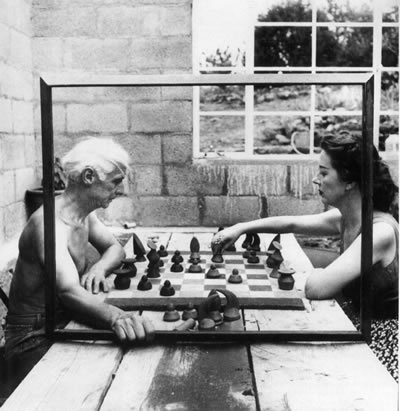

max ernst & dorothea tanningDespite or because of our common trait of shyness, Jane and I soon became friends, and I met other friends of hers and Kenneth's, most of whom turned out to be painters and to have had some connections with Hofmann. (This is not the place to wonder why the poets Koch, O'Hara, Schuyler, Guest and myself gravitated towards painters; probably it was merely because the particular painters we knew happened to be more fun that the poets, though I don't think there were very many poets in those days.)

max ernst & dorothea tanningDespite or because of our common trait of shyness, Jane and I soon became friends, and I met other friends of hers and Kenneth's, most of whom turned out to be painters and to have had some connections with Hofmann. (This is not the place to wonder why the poets Koch, O'Hara, Schuyler, Guest and myself gravitated towards painters; probably it was merely because the particular painters we knew happened to be more fun that the poets, though I don't think there were very many poets in those days.)

Al Kresch, Near CoshectonThere was Nell Blaine, whom the others seemed in awe of and who differed from them in championing a kind of geometric abstraction inflected by Léger and Hélion. There were Larry Rivers, Robert de Niro and Al Kresch, who painted in a loose figurative style that echoed Bonnard and Matisse but with an edge of frenzy or anxiety that meant New York; I found their work particularly exciting. And there was Jane, whose paintings of the time I still don't remember very clearly beyond the the fact that they seemed to accommodate both geometry and Expressionist surges, and they struck me at first as tentative, a quality I have since come ot admire and consider one of her strengths, having concluded that most good things are tentative, or should be if they aren't.

Al Kresch, Near CoshectonThere was Nell Blaine, whom the others seemed in awe of and who differed from them in championing a kind of geometric abstraction inflected by Léger and Hélion. There were Larry Rivers, Robert de Niro and Al Kresch, who painted in a loose figurative style that echoed Bonnard and Matisse but with an edge of frenzy or anxiety that meant New York; I found their work particularly exciting. And there was Jane, whose paintings of the time I still don't remember very clearly beyond the the fact that they seemed to accommodate both geometry and Expressionist surges, and they struck me at first as tentative, a quality I have since come ot admire and consider one of her strengths, having concluded that most good things are tentative, or should be if they aren't.

At any rate, Jane's work was shortly to change drastically, as were mine and that of the other people I knew. I hadn't realized it, but my arrival in New York coincided with the cresting of the "heroic" period of Abstract Expressionism, as it was later to be known, and somehow we all seemed to benefit from this strong moment even if we paid little attention to it and seemed to be going our separate ways. We were in awe of de Kooning, Pollock, Rothko and Motherwell and not too sure of exactly what they were doing.

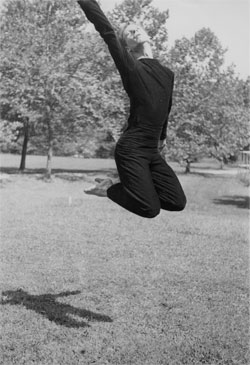

merce cunninghamBut there were other things to attend to: concerts of John Cage's music, Merce Cunningham's dances, the Living Theatre, but also talking and going to movies and getting ripped and hanging out and then discussing it all over the phone: I could see all of this entering into Jane's work and Larry's and my own. And then there were the big shows at the Museum of Modern Art, whose permanent collection alone was stimulation enough for one's everyday needs. I had come down from Cambridge to catch the historic Bonnard show in the spring of 1948, unaware of how it was already affecting a generation of younger painters who would be my friends, especially Larry Rivers, who turned from playing jazz to painting at that moment of his life.

merce cunninghamBut there were other things to attend to: concerts of John Cage's music, Merce Cunningham's dances, the Living Theatre, but also talking and going to movies and getting ripped and hanging out and then discussing it all over the phone: I could see all of this entering into Jane's work and Larry's and my own. And then there were the big shows at the Museum of Modern Art, whose permanent collection alone was stimulation enough for one's everyday needs. I had come down from Cambridge to catch the historic Bonnard show in the spring of 1948, unaware of how it was already affecting a generation of younger painters who would be my friends, especially Larry Rivers, who turned from playing jazz to painting at that moment of his life.

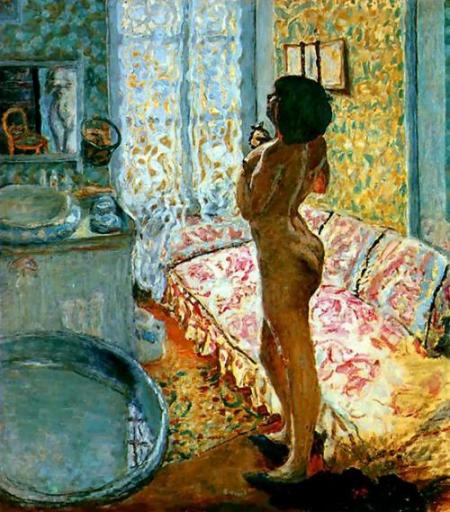

Bonnard, Model in BacklightAnd soon there would be equally breathtaking shows of Munch, Soutine, Vuillard and Matisse, in each of whom - regardless of the differences that separate them - one finds a visceral sensual message sharpened by a shrill music or perfume emanating from the paint that seemed to affect my painter friends like catnip.

Bonnard, Model in BacklightAnd soon there would be equally breathtaking shows of Munch, Soutine, Vuillard and Matisse, in each of whom - regardless of the differences that separate them - one finds a visceral sensual message sharpened by a shrill music or perfume emanating from the paint that seemed to affect my painter friends like catnip.

Soutine, in particular, who seems to have gone back to being a secondary modern master after the heady revelation of his Museum of Modern Art show in 1950, but whose time will undoubtedly come again, was full of possibilities for painters and poets. The fact that the sky could come crashing joyously into the grass, that trees could dance upside down and houses roll over like cats eager to have their tummies scratched was something I hadn't realized before, and I began pushing my poems around and standing words on end.

Soutine's "View of Ceret"It seemed to fire Jane with a new and earthy reverence toward the classic painting she had admired from a distance, perhaps, before. Thus she repainted Watteau's "Le Mezzetin" with an angry, loaded brush, obliterating the musician's features and squishing the grove behind him into a foaming whirlpool, yet the result is noble, joyful, generous: qualities that subsist today in her painting, though the context is calmer now than it was then.

Soutine's "View of Ceret"It seemed to fire Jane with a new and earthy reverence toward the classic painting she had admired from a distance, perhaps, before. Thus she repainted Watteau's "Le Mezzetin" with an angry, loaded brush, obliterating the musician's features and squishing the grove behind him into a foaming whirlpool, yet the result is noble, joyful, generous: qualities that subsist today in her painting, though the context is calmer now than it was then.

The one thing lacking in our privileged little world (privileged because it was a kind of balcony overlooking the interestingly chaotic events happening in the bigger worlds outside) was the arrival of Frank O'Hara to kind of cobble everything together and tell us what we and they were doing. This happened in 1951, but before that Jane had gone out to visit him in Ann Arbor and painted a memorable portrait of him, in which Abstract Expressionism certainly inspired the wild brushwork rolling around like so many loose cannon, but which never loses sight of the fact that it is a portrait, and an eerily exact one at that.

After the early period of absorbing influences from the art and other things going on around one comes a period consolidation when one locks the door in order to sort out what one has to make of it what one can. It's not a question - at least I hope it isn't - of shutting oneself off from further influences: these do arrive, and sometimes, although rarely, can outweigh the earlier ones. It's rather a question of conserving and using what one has acquired. The period of Analytical Cubism and its successor Synthetic Cubism is a neat model for this process, and there will always be those who prefer the crude energy of the early phase to the more sedate and reflective realizations of the latter.

Picasso's "Still Life With Chair Chaning"Although I have a slight preference for the latter, I know that I would hate to be deprived of either. I feel that my own progress as a writer began with my half-consciously imitating the work that had struck me when I was young and new; later on came a doubting phase in which I was examining things and taking them apart without being able to put them back together to my liking.

Picasso's "Still Life With Chair Chaning"Although I have a slight preference for the latter, I know that I would hate to be deprived of either. I feel that my own progress as a writer began with my half-consciously imitating the work that had struck me when I was young and new; later on came a doubting phase in which I was examining things and taking them apart without being able to put them back together to my liking.

I am still trying to do that; meanwhile the steps I've outlined recur in a different order over a long period of within a short one. This far longer time is that of being on one's own, of having "graduated" and having to live with the pleasures and perils of independence.

In the case of Jane Freilicher one can see similar patterns. After the rough ecstasy of the Watteau copy or a frenetic Japanese landscape she once did from a postcard came a phase in the mid-1950s when she seemed to be wryly copying what she saw, as though inviting the spectator to share her discovering of how impossible it is really to get anything down, get anything right: examples might be the painting done after a photograph by Nadar of a Second Empire horizontale (vertical for the purposes of the photograph) with sausage curls; or a still life whose main subject is a folded Persian rug precisely delineated with no attempt to hide the face of the hard work involved. Her realism is far from the "magic" kind that tries to conceal the effort behind its making and pretends to have sprung full-blown onto the canvas.

Such miracles are after all minor. Both suave facture and heavily-worked over passages clash profitably here, as they do in life, and they continue to do so in her painting, though more subtly today than then. That is what I mean by "tentative." Nothing is ever taken for granted; the paintings do not look as if they took themselves for granted, and they remind us that we shouldn't take ourselves for granted, either. Each is like a separate and valuable life coming into being.

I was an amateur painter long enough to realize that the main temptation when painting from a model is to generalize. No one is ever going to believe the color of that apple, one says to oneself, therefore I'll make it more the color that apples "really" are. The model isn't looking like herself today - we'll have to do something about that. Or another person is seated on the grass in such a way that you would swear that the tree branch fifty feet behind him is coming out of his ear. So lesser artists correct in nature in a misguided attempt at heightened realism, forgetting that the real is not only what one sees but also a result of how one sees it, inattentively, inaccurately perhaps, but nevertheless that is how it is coming through to us, and to deny this is to kill the life of the picture. It seems that Jane's long career has been one attempt to correct this misguided, even blasphemous, state of affairs; to let things, finally, be.

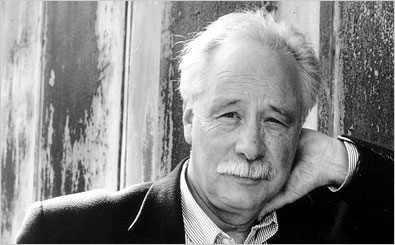

John Ashbery is a poet and critic living in New York. This essay is excerpted from here.

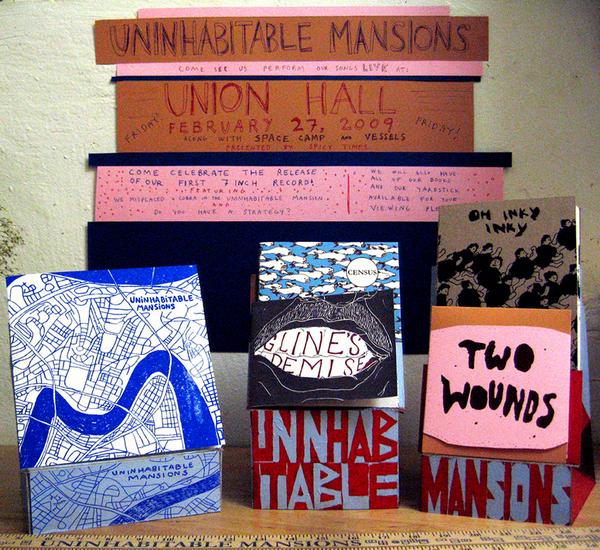

"This Drift" - Uninhabitable Mansions (mp3)

"Static State" - Uninhabitable Mansions (mp3) highly recommended

"The Brain Is A Slow Wave" - Uninhabitable Mansions (mp3)

John Ashbery,

John Ashbery,  jane freilicher

jane freilicher