BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Ended Up Wearing Mittens

Friday, August 7, 2015 at 11:14AM

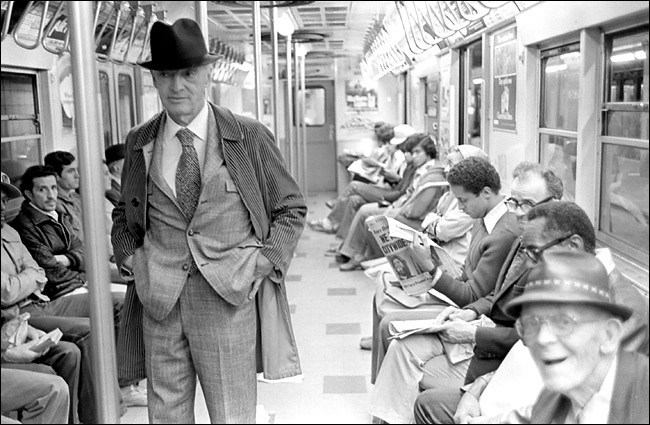

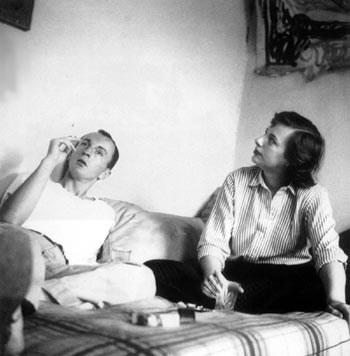

Friday, August 7, 2015 at 11:14AM  photo by liz donadio

photo by liz donadio

Dry Season

by RACHEL MONROE

1

For most of December, it was 45 degrees inside our house, and I only took off my long underwear to get in the shower. Even then, the few bare-legged seconds were miserable enough that I mostly didn’t bathe. It didn’t seem all that important, suddenly; my boyfriend and I had broken up, and I couldn’t imagine ever wanting to look at another human being again. What was dating but spending time talking to someone you would eventually break up with?

But being alone wasn’t much fun, either. I cooked wearing mittens, puffing out sad clouds of breath into the cluttered kitchen. I felt sorry for myself. I couldn’t stand being in my room, but outside it was even colder, so I stayed in and sulked. My bed became a nest of Heath Bar wrappers, half-read books, papers I was supposed to grade. In the middle of the night, I’d stretch my toes and touch a spoon. Tangled sheets, dust that was somehow unvacuumable, shards of glass on the floor from whatever the cats had knocked over in the night. I was incredibly boring to be around. I kept apologizing for this, boringly.

The things I found pleasure in embarrassed me: exfoliating scrubs I couldn’t really afford, Jane Austen, when my cats fell off the table. Licorice tea. Kate Bush. BBC miniserieses. I started reading Middlemarch and wouldn’t shut up about it for weeks. I got kind of fat. I told my roommates everything (I needed to tell someone). No one would kiss me. The winter started to feel infinite.

photo by liz donadio

photo by liz donadio

2

The problem that Virginia Woolf doesn’t deal with — and so, perhaps, those stones, that river — is that once you have the room of your own, you still have to sit there, in your chair, with your own brain.

Marion Milner doesn’t address Woolf directly in A Life of One’s Own (published in 1933, five years after A Room of One’s Own, and out of print for nearly 30 years until it was recently reissued by Routledge), though there’s the clear reference of her title. But while Woolf worried more about the systematic oppression of women and its impact on their creative integrity, Milner’s struggle takes place within the bounds of her own brain.

Basically, Milner wanted to figure out what she wanted. She starts out thinking it’s a simple question worth an afternoon of introspection, and then quickly figures out that it’s harder than it looks; she’s much better at tricking herself, pleasing other people, obsessing about her hair, and feeling vaguely anxious about nothing in particular. And so, A Life of One’s Own is a document of seven years worth of Milner trying to notice the way her brain works and then messing with it through introspection, automatic writing, annotated lists, thought experiments, and sketches done with her eyes closed. She doesn’t want to be your guide or your guru; she just wants to walk you through her experience, and hopes you may pick up something of interest along the way.

Milner started her project when she was 26, and finished the book at 33. Even though all this took place more than 80 years ago, there’s plenty here for, say, a thoughtful, creative, anxious person in her late 20s to relate to. We know we should know better by now, but we don't.

Okay, I’ll presume: Milner could be you. (And by "you", I guess I mean me.) She doesn't know what she wants, so she takes out a blank piece of paper and writes WANTS in big letters at the top, then comes up with dozens of things, none of which are quite right. Her list, in part:

To think out why I can’t ‘get at people.’

To buy silk stockings — I bought the wrong ones.

To make S. think I’m not so innocent as I look — in fact, rather a woman of the world — did I?

To make love with someone I loved — I didn’t because there wasn’t anyone.

She is frustrated with herself; she says things, then takes them back; she can’t keep her thoughts straight:

I’ve discovered where a great part of my thought goes. I was thinking about my new frock and red shoes.

At the Club I wanted T. to be thinking ‘What a charming and interesting-looking girl’ although I hate his voice and face.

So you’ve thought — what have you done, a little work, a little vague chat?

I don’t know what I want. I’m a cork bobbing on the tide.

I don’t feel very much like writing down my soul’s adventures.

I liked the smooth roundness of my body in my bath but would like someone else to like it.

She tries to trust — but can't completely — the "still small voice... that tells me in spite of the clatter of the crowd, 'This is ludicrous, absurd,' 'That is stupendous, immense.'"

But what tricky things to track, your thoughts. As soon as you start to look, they change shape or sink back into the murk of your mind, like the blobs in a lava lamp. They don’t fit easily on spreadsheets, something Milner — trained in psychology, surrounded by scientists — struggles with at first. But she found that she "could not afford to ignore" this "private reality, a reality of feeling rather than knowing." This private reality either does not exist or does not matter to "the scientist" (a specter who haunts the book, a judgmental figure in a white coat, frowning), but Milner happily co-opts scientific language and methods for her own uses; the book is full of observations, hypotheses, tests, re-formulations.

As she sums it up in the preface, A Life of One’s Own is her account of her attempt "to manage my life, not according to tradition, or authority, or rational theory, but by experiment." Or, as the haiku-like subhead for chapter one puts it: "Discovering that I have nothing to live by/I decide to study the facts of my life/By this I hope to find out what is true for me."

Some of that experimentation is through language, through the search for the right verbs and metaphors to translate her mind’s movement. It keeps secrets. It noses for crumbs. It spreads its tentacles, or narrows into a focussed beam of light. It behaves like water, a worm, a butterfly, a baby, a room that needs sweeping, beetles skimming the surface of a pond. Her ideas are "strange birds seen in remote marshes."

photograph by liz donadio

photograph by liz donadio

3

In “On Self-Respect,” Joan Didion looks back at a "dry season" from her own past and "marvel[s] that a mind on the outs with itself should have nonetheless made painstaking record of its every tremor." But isn’t that exactly how it goes? When I'm happy, I'm too busy swimming or kissing or eating cookies to track the topography of my moods; when I’m uncomfortable — mentally, I mean — I poke and poke and poke at my brain as if it were a sore tooth.

Is this what wallowing is? Is this how a person becomes boring — a brain that spends all day chewing on its own misery? Milner finishes her book in London in 1933, as fraught a time as any, but politics don’t enter into her account at all. Milner’s husband, baby, parents, friends, and colleagues barely warrant a mention. A Life of One’s Own is, in its essence, an exercise in self-absorption.

For a while, I liked to pretend that Joan Didion was my spirit animal. If I found myself whining (mentally, I mean), spirit-Joan would slap me hard enough to sting. She did it out of love. Spirit-Joan says: The fastest way to alienate yourself from the world is to let your worry about your worry keep you at arm’s length from everyone you know, even yourself. Worrying about your own boring self-absorption is certainly no way to become more boringly self-absorbed. Spirit-Joan says: Get some self-respect.

While I was reading it, I talked about A Life of One’s Own so much — maybe because I was happy to have something to discuss that wasn’t my own sadness, or maybe because talking about this book was a different way of talking about my own sadness — that three of my friends bought it. Then I started to get nervous. Wasn’t there something kind of Oprah magazine about the whole thing, only made a bit exotic through 80 intervening years and the fact that Milner calls dresses "frocks"? WWJDS (What Would Joan Didion Say)?

I think what I mean is, is it okay to think about yourself this much? What about the rest of the world — its orphans and endangered species and your best friend’s lost cat?

photo by liz donadio

photo by liz donadio

4

Consider the scene near the end of Middlemarch, after our heartbroken heroine, Dorothea, has spent the night crying on the floor, she wakes up calm and goes to the window:

...there was light piercing into the room. She opened her curtains, and looked out towards the bit of road that lay in view, with fields beyond, outside the entrance-gates. On the road there was a man with a bundle on his back and a woman carrying her baby; in the field she could see figures moving — perhaps the shepherd with his dog. Far off in the bending sky was the pearly light; and she felt the largeness of the world and the manifold wakings of men to labour and endurance. She was a part of that involuntary, palpitating life, and could neither look out on it from her luxurious shelter as a mere spectator, nor hide her eyes in selfish complaining.

And a parallel scene toward the end of A Life of One’s Own: Milner is on a weekend steamer train out of London, feeling conflicted and confused about her professional life, until she’s struck by the half-second image of "a fat old woman in apron and rolled sleeves surveying her grimy back garden from her doorstep."

An educated woman, trapped in her own head, looks out the window of her mansion/steamer train and sees a her poorer, working twin. Both Milner and Dorothea receive the image as something of a knock on the head reminding them of the wider world, with its gardens and babies and chores to get done. Of course, neither Dorothea nor Milner goes on to interact with these working women; instead, they’re just an occasion for epiphany, and the privilege inherent in that is something to save to dwell on on a gloomier day.

The point is, Milner dives into her brain and comes out the other side. Three-quarters of the way through A Life of One’s Own, something changes; other people start to creep in the edges of the narrative. Toward the end of her experiment, Milner is amazed to find that, instead of finding transcendence through nature and solitude — a major theme of the first half of the book — she now "chiefly reckoned each day’s catch of happiness in terms of [her] relationships with others." She marvels in the wordless communion that comes from "spreading myself out towards a person," sharing moods, even in silence. She gets really into sweeping: "I seemed to like it because it was a kind of communication, it expressed my feeling for the house I kept clean and the people who lived in it.” Once she calms down her own mind, other minds start to matter.

Still, how to get there? Ultimately, for me, the most instructive thing in the book isn’t any of Milner’s brain-tricks or explicit revelations; it’s the way the Milner who writes the book (age 33) treats the Milner of the early diary entries and experiments (age 26): with a sort of fond blend of exasperation and empathy. What if we could, for one afternoon, hang out with an older, more chilled out, more self-accepting version of ourselves? I would probably take mine on a long walk and talk about boys and cry. Just like how sometimes I think about time traveling to hang out with my overwrought 20 year-old self, and just brushing her hair and cooking her a big breakfast.

Midway through A Life of One’s Own, Milner experiments with sketching a dragon: "I could not have said at all what it meant, I only knew that I thought it would be fun to have a picture of all that I disliked in myself." Which is a funny idea of fun. But why not? It can be fun to look at your own sadness or anxiety or general mental clumsiness. And it can be fun to come out the other side of it, and look back fondly, and then go out to meet the world.

Rachel Monroe is a contributor to This Recording.

Photographs by Liz Donadio.

"Talk About It" - Dr. Dre ft. King Mez & Justus (mp3)

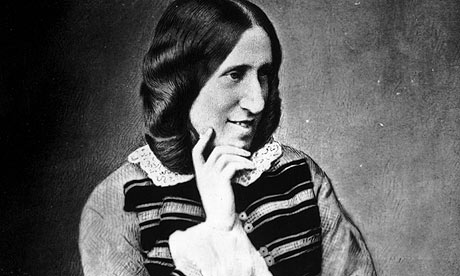

george eliot,

george eliot,  virginia woolf

virginia woolf