Mr. Bush In Baseball

by DAMIAN WEBER

Lighter Fluid

Coach walked out to the bullpen — maybe someone needed a throwing partner. He looked over his shoulder so he wasn’t clocked from hundreds of flying balls, hit from batting practice, hit from infield practice, thrown to first, or thrown in from the outfield.

“Hey, Coach,” Kenny Rogers said. He was pitching tonight and had on his blue warmup jacket. He got touched up last time out and lost. But he didn’t look worried — looked like he hadn’t even started his warmup tosses.

“Hey, Coach, man, we need lighter fluid.”

Coach didn’t say anything.

“You think you could get us some?”

“Lighter fluid?

“We were thinking maybe the kitchen.”

“Lighter fluid … for BBQ? They don’t use lighter fluid in the kitchen.”

“Oh. We were going to set Jose’s cleats on fire.”

“Like a hot foot?”

“No, they’ve already got them, hidden.”

“Who does?”

Kenny Rogers didn’t say anything.

“Does he got shoes?”

“Yeah, no, he’s got another pair. These ones are awful. It’s no big deal.”

“Use alcohol,” Coach said, “like rubbing alcohol.”

“We got that?”

Coach looked around. “I’ll get it,” he said.

“Great, thanks Coach.”

“Jesus Christ, you’re pitching tonight.”

Kenny Rogers smiled.

Coach turned around and walked back down the first base line, the sun in his eyes.

What the hell, burning Canseco’s cleats? Don’t they know how sensitive he is? Whatever, no big deal. In all his years in pro ball he never heard of that one. But he never made it to the bigs. Hell, if he tried it when he was playing, he’d have been arrested. His coach would have waved as he was being carted away, would have mouthed quietly, “Don’t fuck with me.”

Coach walked down the steps into the dugout and back to the clubhouse. Nobody paid him any mind. It was quiet — no music. They were playing the sorrow game because they lost last night. They should’ve been out on the field. Maybe they were playing the sorrow game because they were busted.

“Hi-ya boys,” Coach said.

“Hi Coach.”

He slipped back to where they kept the supplies. He found the rubbing alcohol.

How hard was that?

“See-ya boys.”

“See-ya Coach.”

The dark tunnel led to the sunlight. Jogging up the steps and onto the field was still exciting. He wished he were still playing. He wished he were coaching rookie ball, like he was promised.

Coach couldn’t see what the hell Mr. Bush was thinking, leaving baseball. Politics or baseball? It was a no-brainer. He was surprised when Mr. Bush almost ran for governor in 1990, right after he bought the team. He held a press conference to say he wasn’t running for governor—he would win the pennant and be with his family. Damn right. But now it was 1994, and the election was four months away. To listen to Mr. Bush, it was a lock. The state was going Republican and never going back. He jogged out to the bullpen. Why was he running? He walked. He walked up to the outfield wall, opened the door, and went into the bullpen.

Pitchers were getting their throws in. Pop. Thwop. Pop.

“Where’d Kenny go?” he asked Tom House.

“He’s being interviewed.”

Coach looked around and saw a camera. He walked over and listened.

“I don’t want to jinx it, but as long as I can produce, can continue to produce, I want this spot.”

He doesn’t want to jinx it, Jesus.

“The last time you faced the Angels,” the reporter asked, “you didn’t fare too well. Your last outing you didn’t fare too well.”

“Last time out I got ahead of myself. Tonight I’m going to throw the ball and let them put it in play. I need to pitch at them. Go after them. Work quick. I was too pretty last time out.”

“What about Bo Jackson?”

“Pudge feels like if we pitch him high … nothing he can catch up to.”

“How’s the slider?”

“It’s good to be home, it does good in the heat.”

“Kenny, you’ve had good stuff lately, we hope you do well against the Angels tonight.”

“Thanks.”

Kenny walked away from the reporter.

Coach tossed him the bottle.

“Thanks Coach.”

Laura

“Coach, good, there you are,” Izzy said. “I can’t find George … Laura’s on the phone.”

“What number’s she on?”

“Two.”

“Okay,” he shrugged, “I’ll take it.”

“Thanks, Coach.”

What the hell? Why did he have to do it? Whatever. Izzy knew he was friends with Laura. He was just a kid, an assistant to Mr. Bush. But not like Coach, not in baseball. He signed on to help with the election—a true believer. His name wasn’t Izzy either, but Mr. Bush gave everyone nicknames. Izzy hated his. The best part—it was also the name of the mascot for the upcoming 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. The blue sperm in sneakers. Olympic rings around his tail. Dead eyes.

In fifteen minutes Mr. Bush would be on the field talking to reporters. But Coach didn’t need to keep Laura waiting. He walked over to the blue phone and picked up extension two.

“Hi, Laura?”

“Couldn’t find him, huh?”

“No, sorry, I don’t know where he is.”

“Okay, thanks, that’s okay.”

“I’ll let him know.”

“Thanks.”

Laura said. “When you heading home?”

“It’s looking like August twelve.”

“Tell Mary, I said hi.”

“I will, thanks.”

“And the girls.”

“I will.”

“Tell George he’ll probably see me.”

“Okay.”

“I’m thinking about showing up.”

“You should.”

“Okay, see you soon.”

“Okay, see you.”

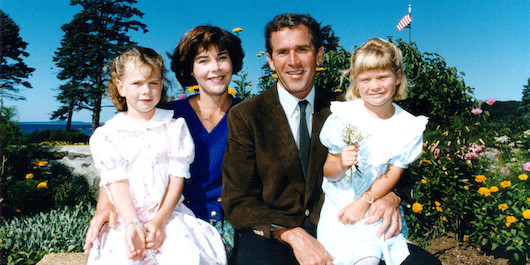

Coach loved that woman. So did his wife, Mary. That was why Laura was always prodding him to go home. She knew he was spinning his wheels. The four of them were good friends, and now, all these years later, their daughters were friends. They had been good friends since the first night they met.

Mr. Bush had walked up to him in a bar in Midland, when Coach and Mary were having a drink, celebrating their anniversary, 8 years. A quiet little bar, not a honky-tonk in Midland playing Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. Those days were ahead.

“Hi, I’m George Bush.”

“Yeah, I know, you’re George Bush’s son.”

They shook hands.

“That’s right.”

“Nice to meet you. I’m Bill.”

“Hi,” George said to Mary, shaking her hand.

“Hi,” she said, “Mary.”

“Hi-ya, Mary.”

George turned to Bill. “Yeah, I know you, you’re Bill Davis, pitcher for Tulsa, drafted out of Midland. Only one, ever.”

“I used to pitch for Tulsa.”

“You got drafted twice right?”

“I went back to school, that’s right.”

“I like that story. I heard it before, I think, you quit baseball, then came back.”

“Something like that.”

“And you did good your second time through.”

“I did better.”

“You didn’t make it out of rookie ball at first.”

“No, that’s right.”

“And then you went to school, community college, and started playing ball again.”

“After a while … I didn’t want to play again.”

“How was it being back? Did you miss it?”

“I did. A lot. I tried to make the most of it.”

“And you did.”

Coach nodded.

“Let me ask you, did you ever think you’d get drafted again?”

Coach looked around. “I didn’t, no, not until Joe Marchese. Not until he talked to me.”

“Oh Joe, I love Joe. What’d he say?”

“He asked me what I would do with a second chance.”

Mr. Bush didn’t say anything.

“I told him I would do everything I could, that there was no way I wouldn’t do everything I could, every day. He asked me about why I left, and I told him I felt like I was a bother, that I shouldn’t bother. He told me, he said, if the Texas Rangers want you, and they think you’re playing Class A ball, that doesn’t mean that you’re not good enough for Tulsa, it means you’re a heck of a good ball player. It means you do what your coaches tell you and you might make it. He said pitchers are tough, some move up too quick, get ruined, some don’t get better, some never get a chance. He told me don’t worry about bothering anyone until I get released. He told me to never do what I did again.”

“And you didn’t.”

“I told him I wouldn’t ever, I wouldn’t dream of it. That I wanted to pitch.”

“You had a great run, Bill, I followed you the whole way.”

“Thanks, sir. I was sad to leave.”

“I bet. Let me ask you, now what are you doing?”

“I’m coaching, sir. I want to coach.”

“High school, right? You ever thought about getting back into baseball?”

“Yes, sir. Rookie ball, a pitching coach.”

“No luck?”

Coach shook his head.

“Too bad, that’s a great dream you got Bill. There’s more to this story, I know it. I want my wife to hear it, Laura … to meet you. You got to come over for dinner. She’s got to meet you.”

“Yes sir, I’d like that.”

“Mary? Please?” Mr. Bush asked.

“We’d love to,” she said.

“Ok great,” Mr. Bush said, “this’ll be fun.” He grinned.

“We got two little daughters, if you don’t mind if we bring them too?"

“That’s great, how old are they?”

“Two and three, four soon, Emily and Melissa. It’d make it a lot easier.”

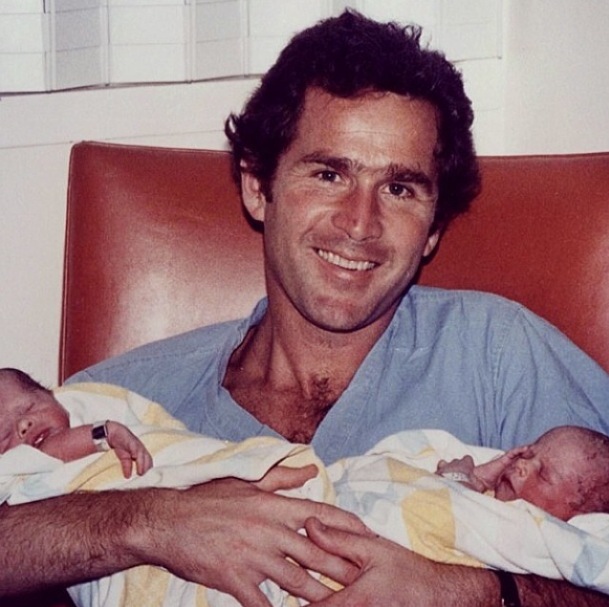

“That’s great, no, Laura would love it. We’ve got two daughters ourselves. Twins, eleven months. I love it, this’ll be fun. It was good to meet you Bill.”

“You too, sir.”

“Hey, George, okay?”

“Okay, George.”

“Bye, Mary.”

Softball

Where the hell was Mr. Bush, anyway? Coach scanned the field and saw a group of reporters by the dugout. There. Probably letting the press have at him. Other owners didn’t do that.

He was being asked softball questions from his buddies, damn sports writers.

“You think the players’ll strike?”

“I don’t think anything’ll change. The players are playing poker with the only resource we got in baseball, our fans.”

“Are you optimistic the season can be saved?”

“No, I’m not. The owners appear united, more than they’ve ever been. And I would suspect—and I can only speak from an ownership perspective—but the owners would be prepared to sit out the season, now that the players are leaving.”

He kicked a boot up on the railing and leaned in.

“Obviously I pray every day there’s not. And listen, we’re making good progress, sometimes it’s hard to tell. Sides are coming together. This is part of the way it works. But the owners aren’t backing down on this one. They’re sick of getting pushed around. It’s the worst it’s ever been. It’s bad.”

“How’s the campaign going George, you going to win?”

“Good, good, but this shouldn’t be a campaign of insinuation, a few funny sound bites. This ought to be a good and honest debate about what’s best for Texas. Let me put it to you this way, if people are happy with the schools then I’m not the right person. I’m going to let parents and teachers and administrators develop the programs. If people think, as the governor does, that violent crime is down and everything is safe, on the streets, then don’t vote for me. I don’t think that way. I hear from too many how dangerous their lives are.”

“Hope you win, George.”

“Thanks, we got to work to make Texas better. I view Texas … a way of life. I don’t want Texas to be like California. I believe everybody should be responsible, for what they say and do. Our leaders should be judged by results, not by entertaining personalities, not by sound bites.”

Coach walked away, he hated politics. He didn’t want Mr. Bush to run for governor. Why would anyone want to leave baseball? The only thing Coach hated more than politics was the business of baseball. He didn’t care whose fault the strike was—the greedy owners or the greedy players. Ken Griffey Jr. was shooting for 62, Albert Bell was going for the Triple Crown, and Tony Gwynn was hitting .400. And the Rangers were in first.

He took his cues from Mr. Bush, and Mr. Bush wanted the games to be played. He built a new stadium, they had record attendance, they were leading the division, and they were going to the playoffs. Don’t jinx it. Coach made it to their seats, first base side, first row, by the Rangers’ dugout. Primo. Mr. Bush was different from every other owner in baseball, who all sat up top in the owners’ boxes and never talked to fans.

No, if you wanted to tell Mr. Bush what you thought, if you wanted to shake his hand and tell him you hope he beats governor Ann Richards, all you had to do was say hi. He liked sitting down here because when he yelled onto the field, the players heard him. Like that time Commissioner Fay Vincent was his guest and the game went into extra innings. Mr. Bush yelled to Rafael Palmeiro, “Hey, Raffy! The commissioner’s getting tired. Hit one out of here.”

Fay was embarrassed, but floored when Raffy did.

Coach looked at the big TV to get the Angels’ lineup. The rookie Lorraine was pitching. What the hell? In his major league debut against the Baltimore Orioles he gave up four runs on nine hits in three innings with two walks and no strikeouts. Next game he gave up seven runs on eight hits in four innings with four walks. An Earned Run Average of 12.91.

Season the kid. Of all the things to do to a man, to his dream, to his career. Coach saw it a lot. Happened to him once.

Top of the First

Coach wanted to go home. To Midland. Emily, his daughter, would be playing college ball this fall at TWU and was moving in a month. She played third or first—a slugger, great left-handed swing. He never tinkered with it once. His other daughter, Missy, was starting her junior year in high school. She played softball too, plus volleyball and soccer. But it was summer so they were playing summer ball, on the team he used to coach—his team. They were 15-1 this summer, and they would probably go 16-1. Except Coach would never say that, wouldn’t jinx it. Cara Stanley, another girl on his team, was heading to UT Austin to pitch. She was the best player he’d ever coached. Damn, he should’ve been there this summer.

Mr. Bush came down the steps. “Coach,” he said, “you keeping score?”

“Yup.”

He squeezed around Coach and sat down.

“Thanks buddy, this is going to be great. You got a beer yet?”

“No, not yet.”

“Let’s get you one.”

“I’m okay.”

Mr. Bush was shitting him—they both didn’t drink. Not anymore.

First baseman, Chad Curtis, was announced over the PA by Chuck Morgan, with little enthusiasm. The crowd clapped a little. Not for Chad Curtis, but because the game was starting. Also for Kenny Rogers.

Kenny Rogers’ first pitch was outside but the ump called it a strike.

Good. First learn the ump’s strike zone, especially how far outside. And how low.

The second pitch was a breaking ball in the dirt. The catcher caught it and threw it back. The ump didn’t ask for a new ball.

Good again.

Rogers went into his windup but the batter lifted his hand and called time.

Rogers didn’t step off the rubber. Coach liked that—made him look like he wasn’t scared. Hell, bored.

Rogers missed again. And again. The count was 3-1.

“Don’t walk the leadoff man,” Coach said.

“C’mon, Kenny!” Mr. Bush yelled.

Rogers painted the inside part of the plate for strike two.

Chad Curtis looked back at the ump and said something.

“Can you believe this guy?” Mr. Bush asked.

“Not smart.”

Coach and Mr. Bush stood up and clapped because there were two strikes.

Chad Curtis took forever. He was still looking down when Rogers started his motion. Same pitch. Got him looking. The catcher, Pudge, threw the ball around the horn.

“Way to go Kenny!” Mr. Bush yelled.

Coach clapped. He liked how Rogers looked. “Rogers is working fast tonight.”

“The Gambler,” Mr. Bush said. “Dealing.”

They called him that because of the song by Kenny Rogers, the singer.

“You got to know when to hold’em,” Mr. Bush sang, “know when to fold’em, know when to walk away, know when to run.”

He elbowed Coach to start.

Coach sang too, “You never count your money, sitting at the table, there’s time enough for counting, when the dealing’s done.”

The Girls

Number seventeen, Spike Owen, was announced over the P.A.

Coach liked Spike Owen, liked his stance. He looked like a smart hitter.

He punched the first pitch the opposite way, foul.

He was a smart hitter.

“You think he’s behind?” Mr. Bush asked.

“I was thinking he was going the other way with it.”

“We don’t have anyone’ll do that.”

Coach nodded.

Spike Owen hit a dribbler to the shortstop, who threw it to first.

2 out.

Will Clark threw the ball around the horn.

“How’s the girls doing?” Mr. Bush asked.

“They’re fifteen and one. Their last game’s tomorrow.”

“That’s great.”

“They did good.”

“Em getting excited yet?”

“No not yet.”

“You going to get Missy a full scholarship too?”

“We’ll see … Missy doesn’t know what she wants to do yet. We did hear though that Cara got accepted at UT Austin.”

“Full-ride?”

“I think so.”

“She was on your team?”

“That’s right, she pitched. She’s pitching.”

“Is that the first player you’ve ever had get picked up?”

“Her and Em, that’s right.”

“That’s great. You’re a great coach, you know that?”

Coach didn’t say anything.

Number twenty-five, Jim Edmonds.

It was Jim Edmonds’ rookie year, and if he went on a tear, he might win Rookie of the Year—if the season weren’t shot because of the strike.

The first pitch was a ball. So was the second.

Not again. What happened to not pitching around them?

The next pitch was low but called a strike. Big Jim Edmonds swung hard and missed the next pitch, which was too high. If that pitch had been anywhere else…

“Love that high heat,” Mr. Bush said.

“Jim does too.”

“Pitch it again.”

“No,” Coach said, “I wouldn’t.”

The next pitch was a fastball outside, and Jim Edmonds nicked it.

“Outside, and late,” Coach said.

“C’mon Kenny.”

The next pitch was a big looping shitball curve that was low and outside. Was it a setup pitch? Was that his put-away pitch?

The payoff pitch was low and outside and Big Jim didn’t swing. Good eye. He stood at the plate waiting for the call. The ump hesitated. Kenny Rogers started walking off the mound. Jim Edmonds started toward first.

But the ump punched him out. “Strike!”

Three down, change sides.

Jim Edmonds got mad, did a little jump, tried to dispute it.

“He’d better take a seat,” Coach said.

“Toss him!” Mr. Bush yelled, then looked around at the crowd, trying to get them to join in. “C’mon ump, don’t take that, get him out of here!”

The crowd joined in, asking the ump to toss him.

Mr. Bush grinned.

But instead the ump walked away. So did Jim. It was the first inning. No one was on base.

Go get your glove, Jim.

It looked like the high strike would be on tonight. And outside. And low.

August 12

“They set the strike date,” Coach said.

“August 12th.”

In two weeks baseball would stop. Maybe the commissioner would end the deadlock “in the best interests of baseball,” like Kuhn did in 1981 when he opened the camps. Maybe the commissioner would act as a negotiator and force the two sides to come to an agreement. But the commissioner had been stripped of those powers. And there wasn’t a commissioner of baseball anymore, not since the owners fired Fay Vincent. He said he wouldn’t leave until the highest court in the land told him to. That lasted 9 days.

To be fair, Mr. Bush was against the firing of Fay Vincent.

“Dang right,” Mr. Bush said, at the time, “I mean, obviously, there are issues, and I come at them from a different perspective. I see it differently is all. I happen to believe this guy is a good, decent man who is being made a scapegoat. My family has been in baseball all my life. And Fay has been a part of that family since the beginning. And now he’s being run out of baseball, dang right, ran out, because, because I don’t really know why. Maybe because he disagrees. But you can’t fire everyone that disagrees. If the country disagrees with the president, he gets four years.”

Mr. Bush’s father was still the president then.

After Fay quit, the owners changed the rules so the commissioner could be fired. They changed the rules so he couldn’t participate in labor disputes. They also took away his power to act in the best interests of baseball. Now the commissioner was a nothing job—kind of always been.

What commissioner would let the owners write a rule that they could fire him? What commissioner would take the job after stripping it of its most important responsibilities? Acting Commissioner Bud Selig.

Baseball was hauled in front of Congress because of the expired labor agreement and the empty commissionership. Bud Selig was asked if he was the commissioner of baseball.

“I am not.”

They asked him why everyone called him commissioner.

“I believe it must be because it may be easier than calling me the chairman of the executive council.”

They asked him when they were going to find a commissioner.

He said it was a long process.

There were strong candidates, including General Colin Powell, Senator George Mitchell, George Herbert Walker Bush, and George Walker Bush.

Mr. Bush was promised the position, as was Senator George Mitchell. That was over a year ago.

Senator George Mitchell informed President Bill Clinton that he was withdrawing his name for consideration for the Supreme Court.

Mr. Bush didn’t hold his breath.

“It’s very hard,” Bud Selig told Congress. “We have a panel with four owners and presidents from each league. And the chancellor of the board. We each are trying as hard as we can to come up with a solution. But we can’t rush this process. It’s very important that baseball has a commissioner. And it’s very important that baseball has the right commissioner.”

“Mr. Commissioner, there is nothing clear in this process except that ownership is dragging its feet.”

Coach didn’t want to ask, didn’t want to bring it up. It never went well when he did, it never worked. But he didn’t care anymore—he couldn’t see why Mr. Bush didn’t accept the commissionership. Why he’d want to leave baseball.

“You think if you took it,” Coach asked, “you could stop the strike?”

Mr. Bush laughed. “See, you do want me to take it. See, look at you.”

Coach didn’t say anything.

“No, no, you want me to. Oh God.”

“You think you could?”

“I don’t know,” Mr. Bush said, “that’d be a short term.”

“I don’t know, sir.”

“A real short term. How am I going to win the election after the owners hand me my ass? How am I going to look serious, running for governor, taking the commissionership?”

Coach didn’t say anything.

“How am I going to be both general manager, commissioner, and then what, fired-ass-commissioner, and governor of Texas?”

“Maybe not.”

“I guess I’d still be owner.”

“And governor, sir, you could be all of them. I mean … do it all.”

“Do it all?”

“I kind of like where it ends you up.”

“What? Also-ran governor of Texas? What? Not commissioner of baseball.”

Coach smiled. “Hated owner.”

Mr. Bush grinned. “They wouldn’t talk to me.”

“Piss them off good.”

“Real good.”

“Win the pennant.”

“That’s the plan.”

“Walk into the governorship.”

“You’re dreaming.”

“You’d be everything.”

“Almost everything.”

Bottom of First

Butch Davis wasn’t a rookie, but this was his first major league at-bat this year, having had a good year with the AAA farm club, Oklahoma City 89ers. He took the first pitch—at least they still played good ball in the minors—a called strike. He hit the next pitch the opposite way, foul.

“He’s going the other way,” Coach said.

“Good,” Mr. Bush agreed, “go with what they give you.”

Butch Davis didn’t try to hit the next pitch the other way, instead he pulled it. It almost ate up third baseman Spike Owen, but he fielded it cleanly. He had all the time in the world, throwing it slowly to first, but it went up the line so that the first baseman, JT Snow, needed to cross the runner.

“That rookie shouldn’t be in there,” Coach said, about the pitcher, Andrew Lorraine. “He’s going to get roughed up.”

“He lost his first two starts, bad.”

“He’s going to lose tonight too,” Mr. Bush added.

“I hate the way they ruin these kids. Can’t they do it right?”

“Now,” Mr. Bush grinned, “this ain’t about you.”

Batting second, the catcher, Ivan Rodriguez!

The crowd cheered Pudge the loudest yet. Pudge said hi, again, to the home plate umpire, Ed Bean. He dug in, hard, making a deep groove. Then he stepped out of the box. He crossed himself and stepped back in. In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

The first pitch was off the plate but called a strike. The ump was giving it to the rookie. The next pitch was a slider that tailed in on Pudge, low and inside. Ball one. The next pitch was a breaking ball that stayed up, probably a slider, belt high. Pudge turned on it. The crowd stood on its feet. Mr. Bush stood on his feet. So did Coach. The left fielder, Jim Edmonds, ran back and toward the line. He set up camp next to the wall and hauled it in. Six more feet. Two out.

Batting Third, number 33, designated hitter, Jose Canseco.

Jose Canseco had been a star on the Oakland Athletics and helped them win two World Series in a row. In 1988 he won the AL MVP and became the first player to hit 40 home runs and steal 40 bases. But his teammates hated him. His home runs weren’t timely. And he was a liability in the field. (It was just last year that a ball bounced off his head and went over the wall for a home run.) So he was traded to the Rangers for Ruben Sierra, their star outfielder. Coach was pissed. Not only did Mr. Bush give Ruben Sierra to their rival, but two pitchers too, Bobby Witt and Jeff Russell. You never trade with a team in your division. Tony LaRussa, the coach of the Oakland Athletics, said he would have made the trade straight up for Sierra. Now they gave them two pitchers too. The trade looked bad right away when all three players did well with their new team. Against their old team. The other reason Coach hated Jose Canseco was because he knew he was using steroids. All of baseball knew. The fans would yell, “Juiced! Juiced! Juiced!” like a train getting faster. Jose would flip down his bat, roll up his sleeves, and flex his right bicep. Which everyone loved and cheered. The fans also liked to howl, “Sterrrrrrrooooids!” When asked if he was juicing, he would become indignant. “If you guys saw what I went through during the off-season, you’d know where this body came from. My brother and I work out about 3 hours a day, six days a week. We play volleyball in the sand to build up the legs, swim to build up the shoulders and back, and then lift weights. Rumors are rumors. If you know they’re not facts, then why worry about it. I’m trying to be like that song, you know, Don’t Worry, Be Happy.”

The first pitch was low and outside but was called a strike. Canseco stood in the box in order to show his displeasure. He was upset because he had been getting rung-up on pitches he thought were balls. He got ejected from the game last night for arguing balls and strikes. Then he mouthed off to the press that the umps were against him. “I’m not getting the same strikes as the other players with similar years and experience.”

The next pitch was also a called strike. Jose choked up on the bat—Coach didn’t know he did that. Every game, you see something new. Jose smoked an inside pitch, thigh high, with a monster swing, holding onto the bat with both hands as it bounced off his shoulder, righting himself by taking a step toward first. Mr. Bush stood up. Coach stood up. Everyone did. The ball had a high arc, a popfly arc, but it landed in the stands, home run. Jose trotted around the bases and shook Will Clark’s hand as he crossed home plate.

“You think it was such a bad trade now?” Mr. Bush asked.

“When he gets ahold of them…” Coach agreed.

The theme music to Superman played over the P.A. The horn section sounded not triumphant, but instead lonely—sad, lonely power.

“He puts butts in seats,” Coach agreed, while disagreeing.

Number 22, First baseman, Will the Thrill Clark.

The crowd cheered a lot. Will Clark was hitting .334 with 79 RBIs but was currently in a 9 for 50 slump. The team let go of Rafael Palmiero in order to pick up Clark. Palmiero had a great season last year, and was a leader in the clubhouse for the other Latino players. Coach was against the trade, both trades, Jose Canseco and Will Clark—so five years ago. So 1989. Will Clark took the first pitch, ball one. Then the second, ball two. He popped up the next pitch, behind the catcher, who ripped off his mask and ran to the backstop. But the ball sailed out of play, not even close, 20 rows back. 2-1.

“Lorraine’s not doing bad,” Coach said. “If he can get out of it.”

“One run ain’t bad, rook,” he said to no one. “Might be a big inning.”

“Just let’em hit it.”

“Clark will get his pitch,” Mr. Bush said, “Will the Thrill will.”

The next pitch was a slider that Clark missed by an inch. 2-2. Protecting the plate, he extended his arms and fought off the next pitch to stay alive, chopping it foul. He watched ball three and brought the count full. The payoff pitch was low and outside, ball four, take your base. Will Clark sprinted to first. Coach was happier about this walk than Canseco’s two out homer. He was getting excited. “Think it’s going to be a big inning,” Mr. Bush said. Coach didn’t want to agree. “Don’t jinx it.”

Batting fourth, left fielder, Juan Gone … zalez!

Juan Gone was hot—hitting safely in six straight games. Coach liked his swing because he got low, and his follow-through was angular, compact, ready to run, not like the other homerun hitters. Even though he won the home run crown last year, and the year before, he was currently hated by management and fans for jaking it. But Coach didn’t think that Juan Gone jaked it, and saw it for what it was, bullshit. Sour grapes for paying him $5 million a year. He was the king, pay him his money. Juan Gone let the first pitch go for ball one. But he hit the next pitch on the ground past the shortstop. Smoked it. By him. A shot. They don’t get more line-drive than that. On the button. 7-game hit streak. Will Clark didn’t dare go to third. “Spirit in the Sky” played over the P.A. When I die and they lay me to rest / Going to go to the place that’s the best / When I lay me down to die / Goin’ up to the spirit in the sky

Ladies and gentlemen, number sixteen, Dean Palmer.

Two on, two out. This was a big scoring inning—get as many as you can. The infield was playing deep. Dean Palmer hit a bloop into center. It fell in. He must have cracked his bat. Will the Thrill scored easily from second. Two nothing Texas. The pitching coach visited the mound to talk to the rookie. There was no one warming up in the pen—still the first inning. “My Angel Was a Centerfold” played over the PA. My blood runs cold / My memory has just been sold / My angel is a centerfold /(Angel is a centerfold) / na na na na na na / na na na na na na na na / na na na na na na / Angel is a centerfold

Angels in the centerfield? Coach heard these songs every day. Damn. Nobody was warming up in the bullpen. They were letting the rook get lit up. They’d call it experience.

“How long can this go on for?” Coach asked. “All night, I hope,” Mr. Bush said.

“This isn’t baseball,” Coach said. He couldn’t stand it. He had to say it. “This is a joke.”

“They got to get that rook out of there,” Mr. Bush agreed. “Lorraine shouldn’t even be in there. They’re ruining the kid.”

“Coach, we’re up.”

Coach knew he wasn’t going to convince Mr. Bush. And he didn’t want to push too hard. All he wanted to do was go home. This wasn’t baseball. Ladies and gentlemen, center fielder, rookie of the year, Rustyyyyyyyyy Greer! Lorraine came back with a good fastball on the inside corner. Maybe the rook wasn’t going to lay down. Maybe he was more resilient than Coach thought. Rusty got under the next pitch and hit a towering pop fly—easy out. Right fielder Bo Jackson settled under it. 3 out.

“Damn,” Mr. Bush said.

“I got to get outta here,” Coach said.

“Where are you going. C’mon.”

“Bathroom.”

“You going to keep score?”

“No,” Coach said, “sorry.”

“Don’t try to sneak away,” Mr. Bush said. “You’re acting all quiet. Looks like you’re going to disappear again.”

“No, no.”

“Look at you Coach, you’re all quiet.”

Coach didn’t say anything.

“Don’t you disappear.”

Mary

Coach walked up the aisle, nodding at people he knew, and then walked down the tunnel into the concourse, which was as tall as a cathedral. He stood in line to get a coffee. The family in front of him was cute, but he didn’t care. It was no good. He needed to go home. He needed to call his wife.

“Hi Coach,” the lady behind the counter said.

“Hi Judy, let me get a coffee, please.”

“Sure. A large, no cream, no sugar?”

“Yes, please.”

“Some game huh?”

“It is, it is,” he said, not wanting to talk. “They’re pounding that rookie good.”

“I hate to see it. I hate these kind of games.”

“As long as it gets them over five hundred.”

“And to the pennant.”

“That’d be something … the playoffs.”

Coach nodded. He wanted to get away. He needed to call Mary. He knew where there was a blue phone, down a hallway where he could talk without having to yell. He said thanks to Judy, walked to the phone and asked for an outside line.

“Hi sweetie.”

“Bill,” she asked, “What’s wrong?”

“No, nothing’s wrong.”

“They’re winning.”

“They are.”

“What’s wrong?”

“No, nothing. I don’t feel good.”

“Your stomach?”

“Uh-huh, my stomach.”

He paused. “I want to come home.”

“Is it bad?”

“No, it’s not.”

“You should stay.”

“I know.”

“It’s that bad, huh?”

“I don’t know. It’s bad.”

“He’s not going to be mad if you leave.”

“No … I mean, I know.”

There was a pause.

“The girls would love it,” she said.

“I could make it for tomorrow.”

“That’d be nice.”

“I’d like that.”

“But you got to tell him,” she said.

“Yes.”

“Tell him you’ll be back.”

“I don’t want to.”

“Talk to him, you can’t walk out.”

“I’m not going to walk out.”

“Just talk to him.”

“I’m going to,” he said, annoyed.

“Ok good,” she said.

“Ok, talk to you soon,” he said, to get off the phone.

“Ok, bye.”

“Bye.”

“Bye, sweetie.”

He was annoyed. Of course, he was going to talk to him—what did she think? Still, he wished he hadn’t gotten short with her. Why was he such a pisser? Still, it was good to talk to her, if even for a minute. He was lost a minute ago, now he was going home. He walked around the stadium toward the outfield, where his office was. He shared his office with Mr. Bush, who had taken the door off the hinges so that his door would always be open. And it worked, players and staff came to see him all the time.

Coach admired the way Mr. Bush worked. He would come in the office, toss his blazer on the floor, plop in his seat, throw his boots up on the desk, pick up the phone, and dive into his work. He ate popcorn all day. His office was a mess, looking at times like he lived there. What Coach liked best was Mr. Bush’s collection of signed baseballs, about 250, signed by Nolan Ryan, Bart Giamatti, Willie Mays, Jeff Bagwell, and every Texas Ranger for the last 20 years. From his years living in Houston, he also had a lot of Astros too. Coach also liked the Astros—they were his National League team.

Coach grabbed his glove, his keys, his spikes, and a book and tossed them in a box. He looked out the window to the field, one last time. “Who would ever want to leave baseball?” he asked himself. He turned away, went downstairs, and headed through the concourse. He thought about leaving, without saying goodbye, right now—no. He promised Mary. And Mr. Bush. And Laura was coming. He’d like to see her. He’d have to. He waited in line to get another coffee, waiting behind a couple with two daughters. When you’re not looking, you see nothing, and then when you look, everything. Like your two daughters in line ahead of you, from 10 years ago. A little lesson you must learn, if you pay attention.

“Hi Judy, could I put this back there?” he asked, handing her the box.

“You going camping?” she asked.

“Going home.”

“Oh, good for you. Tell Mary I said hi.”

“I will thanks.”

Instead of hiding, instead of going to a different seat, he went straight to Mr. Bush. He walked down the aisle toward the field. When he reached his section he needed to wait until the end of the at bat. He stood with a group of four people, while the attendant held them up. But then Rusty Greer got a hit, everyone cheered, and the attendant let them go. No one was at the seats, which was a relief. His score card was there but it hadn’t been filled out since he left. C’mon, Mr. Bush knew how to fill out a score card. What the hell?

The Rangers were now up 4-0, from back to back jacks from Ivan Rodriguez and Jose Canseco. The Rangers had chased the rookie out of the game. He would need to go back to the minors. He should never have been out there. Izzy came down the steps, and took Mr. Bush’s seat.

“What’s up, Izzy?” Coach asked.

“You see Kenny’s perfect?”

Izzy was right—Kenny Rogers hadn’t allowed a hit or a walk, and the Rangers didn’t have an error. “It’d be pretty hard not to.”

“Laura’s coming.”

“Is she here?”

“Right up top.”

“Well c’mon, Izzy, let her down.”

“Yes, sir, I just had to tell you, sorry.”

“Sure, no problem.”

Izzy walked back up the aisle, and Laura came down.

Laura (Again)

Holy Christ, he thought, what am I going to do? But he took a breath and smiled at her.

“Hi Bill,” she said, “It’s still perfect, right? I mean, he is?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

He pointed to Mr. Bush’s seat and said, “Here, have a seat.”

“Thanks.”

She had a book in her hands, and closed it on her lap.

“You’re keeping score?” she asked.

“Every game.”

“You’re such a good friend.”

Coach wanted to say, “Well he does pay me,” or “I’d do it for free,” or “It’s for me,” but instead he nodded.

“How are the twins?” he asked.

“Good, they’re at a friends’. Jenna had a game yesterday. She did well.”

“Is she still the best? She should play college ball.”

“Oh, I think she wants to, we think she does.”

“I love softball,” Coach said. He blurted it out, and now he thought that it sounded funny. What could she say to that? “That and little-league,” he continued, “and high-school. And college softball is the best.”

Laura smiled.

“How’s your girls?” she asked, “you miss them?”

Coach nodded.

“Why don’t you go back there?” She’d asked this question before, almost every time.

“No, I am,” he said, "I’m going back tonight. Pretty soon, in a few minutes.”

“Oh good. So soon?”

“The girls have a game tomorrow I want to go to.”

“You said you wouldn’t be going back for a while.”

“I changed my mind, I talked to Mary. I don’t know what I’m doing here.”

“Are you coming back?”

“I think so.”

“Wow, Bill,” Laura said, “What’s wrong, you’re not coming back?”

“No, I’m coming back.”

“Well, I’m happy for you. Tell Mary I said hi, will you?”

“Yes, of course.”

Coach nodded and stood up, getting ready to leave.

“Bill, sit down,” she said sweetly. He did. “Now,” she said, shifting gears, “do you think it will happen?”

“What’s that?”

“The game … going perfect.”

“Can’t say, or predict, or hope, or even acknowledge it.”

“But it is. It’s wonderful.”

“Well, we don’t want to jinx it.”

Laura laughed. “So superstitious.”

“Look at all the fans here. This is electric.”

“Biggest draw of the season. Biggest draw ever. It’s been a nice night. Not too hot either.”

“No it’s wonderful.”

“Here he comes now,” Coach said. Mr. Bush was coming down the steps, shaking hands.

“Look at this,” he said, “he’s back!”

Coach nodded.

He stood up and tried to give Mr. Bush his seat so he could sit next to Laura.

“No, that’s OK,” he said, “I’m good right here,” sitting on the stairs. “Did you talk him out of it?” he asked Laura.

“He wants to see his daughters’ game,” she said.

“He should, I agree.”

“I always tell him I think he should,” she said.

“I know,” Mr. Bush said. “But are you coming back?” he asked Coach.

“I don’t know. I think so.”

“He doesn’t know!” Mr. Bush scoffed, “he thinks so!”

“I mean, yes.”

“How can you leave now? We’re going to win this thing.”

“I’m coming back,” Coach said.

“What about the playoffs?” Mr. Bush asked.

“I know,” Coach said.

“Well I’ll be damned. Look, call me when you get home. Talk to Mary. Then call me.”

“I will.”

“Look at you, all quiet. You should see yourself, all sad. Like I killed your dog."

“No,” was all Coach could say.

“No?”

“I just don’t want you to think that this has anything to do with you. With how wonderful you’ve been to me.”

“You’ve been wonderful to me too,” Mr. Bush said, “dingbat.”

Coach stood up. “You come back for the playoffs,” Mr. Bush said. “First playoffs ever.”

“I’d like that.”

“Of course you’d like that.”

Coach nodded.

“OK get the hell out of here. Tell Mary hi. Give the girls a hug for me. Tell them I’ll see them soon. I’m coming out there as soon as I can, you hear?”

“OK.”

“OK get out of here. Jesus, you look like you’re going to cry.”

Coach scooted past Mr. Bush and up the steps. He looked back and waved. They waved back. He walked up to the coffee counter and asked Judy for another coffee, and if he could have his box back. She handed him his box.

“He’s still perfect,” she said.

“Not anymore.”

Her face turned so sad.

“I mean, he’s still perfect, but you’re going to jinx it.”

She was relieved, then mad. Happy, then harried.

“He’s going to go all the way,” she said. “He’s coming back from the other night, and everything is perfect! And it’s going to be the Angels! Tonight!”

“You’re right,” Coach said, “he’s looking good. I’m sorry, that’s just a bad habit.”

She made a noise and gave him his coffee. Coach knew to walk away, not to press it, but he turned back. “You’re right, tonight’s the night,” he said, “Kenny’s going to go perfect!” Some people around him cheered and clapped. They all looked at him and smiled. Judy smiled.

He looked away quickly, embarrassed. He slapped someone hi-five, but didn’t look at his face. What the hell was going on? Coach had never seen Judy get mad before. Coach would never have done that before. Never would have jinxed it.

Perfect

Coach was out. That was his chance. His third strike. Once again he was out of the game—would need to make “the adjustment.”

But he wasn’t worried. More like relieved. Go home and watch his daughters play their game tomorrow. Win their game! What the hell? He had a lot of driving ahead of him. He’d probably have to stop somewhere, a rest stop, for a few hours. He didn’t turn the radio to the game. Instead he listened to the news and heard Mr. Bush talking to reporters about making Texas a better place, about working hard to not make it like California. Then the news discussed the looming strike—how it would steal a good part of the season, how neither side would cave.

“The Rangers are still ahead four to nothing in the bottom of the eighth, but that isn’t the real news, the real story is that Kenny Rogers is still perfect, having not allowed a hit or a walk, and if he can keep it up, he will be the 14th player to pitch a perfect game ever in the history of Major League Baseball, and the first left-hander to ever do it in the American League.”

Coach changed the station back to the game, WBAP 820 AM. The inning must have ended because they had gone to commercial. Did that mean it was the top of the ninth? How many times had he seen no-nos broken up in the ninth inning? How much more difficult was it to close the deal? How many times had baseball gotten his hopes up?

Eric Nadel and Mark Holtz came on the air and started to talk about the little fire that was started in the dugout during the fifth inning. “A strange night, you’ll never see a stranger,” Eric Nadel said. “We have more information now about what happened in the Ranger dugout in the top of the fifth inning. Teammates, Texas players, had hidden Jose Canseco’s spikes and he was forced to wear a new pair for today’s game. Seems he’d been wearing them since spring training and they had grown ripe. But after his second homerun of the night, when it was clear he wouldn’t need them anymore, they were ceremoniously, in no ceremony I’ve ever heard of, set on fire and then danced around.”

They laughed. “Nobody really knew what was going on,” Mark Holtz said, “and we didn’t have any word on who started the fire, but we’ve now heard that it was Chris James and Gary Redus. Apparently, with Manager Kevin Kennedy right there. And no attempt to stop it. We were told it was a good bit of fun, and that everyone thought it was just too rich.”

“And now it’s the top of the ninth,” Eric Nadel said, “and Rogers is working on a perfect game. What a strange night. Only in baseball could there be a night like this.”

“It’s because of baseball,” Mark Holtz agreed. “And Rogers is looking good, looks confident. Like he’s not going to give up a walk. He’s been challenging hitters all night.”

“That’s what I been saying,” Coach said to the radio. Eric Nadel called the play by play. “Coming up first is the Wonder Dog, Rex Hudler, who’s hitless tonight, obviously, but who’s exactly the type of player you would expect to find a way to break it up. Scrappy the Wonder Dog, he might get a little slappy and put down a bunt. There used to be a time when it was bad form to slap down a bunt in the ninth inning for the sole purpose of breaking up a no-hitter, but not any longer, those days are behind us. So we can expect some sort of stinger out of Rex, who’s a fine line drive hitter, and can be called on to put the ball in play. And he recorded two put outs last inning, and good plays carry over to good at bats.”

“That’s definitely true,” Coach said.

“But it appears,” Mark Holtz said, “that Dean Palmer hasn’t received the memo. He’s still playing back at third, not protecting against the bunt.”

The first pitch was a called strike. “And now Manager Kevin Kennedy is trying to get Dean Palmer’s attention, to get him to move up a little maybe, to protect the bunt, but it doesn’t look like he sees him.”

“I can tell you I know exactly what Rex Hudler is thinking,” Eric Nadel said, “he’s thinking he’s going to break up this no hitter and lead his team to a comeback. There’s no way he’s going to lie down and let Rogers get the record off him, or his team. Oh, but that’s strike two, can’t bunt now. He’s taken away the bunt. But it didn’t seem that Rex was looking to bunt in anyway. He steps out of the box, trying to slow down Rogers, the pitcher. It doesn’t look like, though, that Rogers is in any way concerned. He won’t step off the rubber. He’s waiting for Hudler to return.”

“Good,” Coach said.

“The oh-two pitch, and he hits it, it’s a line drive to center, center right, it’s falling, it’s going to fall in…no, Rusty Greer’s got it! Rusty Greer left his feet and dove and got it! Good lord, he did it, I didn’t think there was any way he was going to get to that ball. Rusty Greer, playing center for the first time ever, in the majors, tonight, dives, and catches the ball before belly-flopping on the ground, and sliding 10 feet.”

“Oh here,” Mark Holtz added, “and Kenny Rogers is lifting his glove up to him.”

Coach was proud of the rook. He was glad he left his feet. Imagine if the rook pulled up short—he would’ve learned a lesson the hard way. The kid was smart enough to know it already. How did the kid get to it? He must have turned it on, went all out, full-tilt. He left the ground and flopped—and slid and slid. It didn’t hurt, it felt good. But you better leave the ground on anything close, and dive head-first.

“Everyone is on their feet here at Arlington Stadium, applauding the rookie. Definitely the play of the game. As long as Rogers holds. Definitely the moment of the game. Should be a breeze from here out now, that’s how these things go.”

“That was the tough bit, I agree. Now it might be easy.”

Catcher, Chris Turner, was announced over the PA and picked up by the radio.

“The nice thing about a perfect game is,” Mark Holtz said, “that you end with the bottom of the lineup, facing what are, usually, not the best hitters. As we have now their number eight hitter, Chris Turner."

“Chris Turner,” Eric Nadel said, “flied out in the third, and popped up in the sixth. He’s 0 for 2 tonight, as you know, and 1 for 6 lifetime against Rogers.”

“Again,” Mark Holtz said, “third baseman, Dean Palmer, is playing back, not protecting the bunt.”

“Rogers throws a big looping curve,” Eric Nadel said. “It hits the dirt and scoots under Pudge’s glove. It got away from him—no matter, no one on. The crowd has been cheering through the whole at bat, not just after the second strike. Here’s the 0-1, called strike, right down Broadway, with nothing on it. Even up, 1-1.”

“Does Rogers commit here,” Mark Holtz asked, “to continuing to challenge? Or does he start to pitch around hitters?”

“I can’t see why he would change anything now.”

“Just make sure your pitches stay down.”

“And here’s the 1-1,” Eric Nadel said, “And it was down, a slider, hit into the dirt. Beltre has it, pounds his glove, throws to first. Got him, plenty of time.”

“He got him with that slider, they can’t stop hitting the ball into the dirt. That’s a great pitch, the best I’ve ever seen him throw it.”

“They’re pounding it into the dirt.”

“They can’t get under it.”

“One out away,” Eric Nadel said. “And coming up next is Gary DiScarcina, who has grounded out twice tonight. He’s never recorded a hit against Rogers. Ever.”

“He won’t get one here now either,” Mark Holtz added. “You’re right he may not, but you never know.”

“Oh, I know.”

“Well, we’ll see, here comes the first pitch, a big curve, he swung through it. Strike one.”

“That’s really something,” Mark Holtz said, “that Rogers is still throwing curveballs on the first pitch. And to get it for a strike. When he needs it the most. That is really a good sign. He’s on to something else now.”

“It sure is good news, and here’s the 0-1, and he hits it, it’s going to center field, there’s nothing on it. Greer backs up, he’s under it, he’s got it. Rogers has done it, a perfect game, the fourteenth in Major League Baseball history, the first by a Texas Ranger, and the first by a left-hander in the American League!”

“Hello, win column!” Mark Holtz sang. “Hello, Mr. Perfect!”

“Rogers wins the game tonight, 4-0, with 88 pitches, 55 being strikes. And he’s being congratulated on the mound. The whole team is out on the field. Everyone wants to get a piece of him. Manager Kevin Kennedy is on the field. He’s talking in his ear. How much would you like to know what he’s saying?”

“I can tell you what he’s saying,” Mark Holtz said, “he’s saying, you lucky so and so, I can’t believe you, you S.O.B.”

“True indeed,” Eric Nadel said, “And now Rogers lifts Rusty Greer into the air. The crowd is cheering pretty good now. Everyone’s acknowledging that great catch.”

“What a catch for the rookie,” Mark Holtz said. Coach turned off the radio and drove in silence. He couldn’t believe it. Baseball. It was a gift—surprise—exactly what you needed.

Home

Coach drove all night and caught some sleep at a rest stop on I-20 just past Abilene, almost to Sweetwater. He didn’t have any problem sleeping in his truck, and liked that the sun was up when he started again. Back home, he tried to be quiet opening the door. Mary was probably up, but not the girls. He set his box down and went into the kitchen. He didn’t know why he was being quiet. He poured a cup of coffee. The Dallas Morning Star was on the table, opened to the sports section with a picture of Kenny Rogers and the headline, “MASTER ROGERS.”

He could hear the shower running so he sat down and read the paper. “I really tried not to think about it to be honest. It just happened. And we caught these guys at the right time, I think, there’s a couple of guys on the DL, but I think a lot of luck’s involved, you know, they hit some balls right at people. But the play Rusty made was just spectacular, I mean, it wouldn’t have happened without Rusty.”

His daughter Missy came down first. “Dad?” she asked. “Hi Sweetie.”

“What are you doing?” She hugged him. “I don’t know what the hell I’m doing.”

“Are you coming today?”

“Definitely.”

“Em!” she yelled for her sister. He winced.

“Does mom know you’re here?”

“No not yet I don’t think.”

“Em!” Missy yelled again. Coach hated it when they yelled in the house. No, he hated it when they yelled for him when he was in another room. But now it was kind of nice. No, he hated it. “Jesus,” Coach said, “please don’t.”

She ignored him. Thank God. His daughter Emily came down the stairs, ran, stomped, and hugged him.

“Perfect game, huh?”

“Yup.”

“We were listening. Then we saw it on TV. Mom said you called. She thought maybe we’d see you.”

“He’s coming to the game,” Missy said.

“Are you going to Coach? You should be out there.”

“I thought I’d go is all.”

“You know Coach Lee would love it.”

“You got to,” Missy added. “We’ll see.”

“You got to.”

“I’ll ask.”

“Yes!” they both said.

“We’re going to win today,” Em said, “win it all.”

“I don’t doubt it,” Coach said. “You’re definitely going to.”

“We beat them before.”

“Cara’s pitching today.”

“We never had a problem with them before,” Coach said. He was done with the jinx. “I heard you got 3 hits on Tuesday,” he asked Em.

“And two great defensive plays,” Missy answered for her sister.

“Does Coach Lee still have you play way back, almost in the outfield?”

“And I still nail them,” Em said.

“We could use whole teams of you.”

Coach felt bad focusing on Em only—but Em was racking up the hits.

“We’ll ask Coach Lee,” Missy said.

“Oh, he’ll definitely say yes,” Em added.

“No that’s OK. I’ll ask him.”

Mary came in. She didn’t push the girls away but walked up behind them. It was good to see her—god she was pretty.

“I thought maybe you’d be here.”

“I’m pretty ridiculous,” he agreed.

“Did you see the rest of the game?”

“Were you on the field?” Missy asked.

“No not after the game.”

“Oh why not!”

“Did they burn Jose’s cleats?”

“Gary Redus did, and Chris James.”

“Did you see it?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Did they get in trouble?”

Coach chuckled. “Probably not.”

Pulling up to the old field was a good sight. It stretched forever, and behind the outfield fence was a mile of grass. The backstop was far behind home plate, the seats were far away from the foul lines, there was a lot of territory in play—it was a pitchers’ field. A big home field advantage, they would get two extra outs that the other team wouldn’t. Coach helped the girls with their equipment and walked with them up to the team.

“Coach.”

“Coach!”

“Hi, Coach.”

“Did you see it?

“Were you there last night?”

“Are you going to Coach?”

“I hear you’re doing well this summer,” Coach answered.

“Fifteen and one.”

“Today we win it all.”

“We’re the champs.”

“Girls, normally you wouldn’t want to jinx it, but, yeah, you’re going to win it today.”

The girls celebrated.

“Congratulations Cara,” Coach said.

“Thanks, Coach.”

“This team’s got a lot of players good enough to go all the way, and I want you all to play like it. I’ve seen good ballplayers and you’re all good ballplayers. This is one of the best teams I’ve ever seen.”

They celebrated again. He was sitting on the grass, enjoying it. With his ass on the grass, stretching. It wasn’t a major-league field, but it was nice.

“Cara,” he said. She walked over.

“Yeah, Coach.”

“Congrats, kid.”

“Thanks, Coach.”

“I wish I was you. I’d love to go to college and play ball. Take courses I love, and play against the best.”

“Yeah, I’m excited.”

“You know what it’s like to play against the best, right. You concentrate, focus, with everything you have, and you put it in there, and you learn, and you play like a champion in everything you do, and there’s never any reason to not be nice, or friendly, but you play hard and you look like a winner. I’ve been around a lot of winners and you’re definitely a winner. You lead this team every year, and you’re going to lead your next team, whatever team you’re on. You act like a champ and there’s not anyone who will ever not think you’re a champ.”

“Wow, thanks Coach.”

“Now, don’t pitch around them today, go after them, get them to swing early, pop ups and foul balls today. It’s a pitchers’ game today. It’s yours.”

“Wow, thanks Coach, it’s great to have you back.”

Coach was still stretching when Coach Lee came up to him. He got up and shook his hand. “You’ve done a great job this year. The girls have told me everything. It’s been a great year.”

“Thanks, Bill. You going to help us out today?”

“I’d love to if that’s OK.”

“You think you could get first.”

“Sure.”

“You want third? The signs haven’t changed. They’ve changed a little. But they’re easy. The brim is the indicator and the chest wipe is the wipe away.”

“First would be good. I’d like that.”

“I’d like it too. It’s great to see you again.”

The first inning was 3 up 3 down. Cara worked quick and got a lot of pop-ups and foul balls. The leadoff hitter hardly hit the ball, and it dribbled to the first baseman who picked it up and ran back to first. She needed to step on the bag and step off quick because the runner was right behind her. She took it the whole way and didn’t toss it to Cara who was covering. Don’t hurt yourself girls! Coach was in the dugout with Coach Lee. He didn’t say anything. It wasn’t his team.

He looked at Coach Lee. “Looked like it could have gone either way,” Coach Lee said.

“Cara was covering.”

“She had it. She got it herself.”

“You’re right, she did,” Coach agreed. The next batter hit a pop fly into right field, tailing out of play, which Missy flagged down, catching it on the run.

“Good girl,” Coach said to himself. But after the cheering stopped, he yelled so Missy could hear, “Good catch, kid!”

“Thanks dad,” she yelled back.

Cara struck out the third batter who was swinging for the fences. She tricked her on the rise ball. Keep coming at them. The teams switched sides. Coach walked out to the coach’s box next to first base. It was great watching the game from the field, even better than the seats on the front row at Arlington Stadium. This is where you watch the game. Em batted leadoff, taking a few pitches, and then hitting the ball on the ground to the third baseman.

“Run it out,” Coach yelled as Em sprinted to first. “You got it. You got it.”

The throw came in late. She turned around, away from the field, and walked back to the bag. “Way to run, way to run,” he said, patting her on the shoulder. She asked for time. The ump gave it to her. What did she need? She turned to her dad and gave him a hug.

“I’m so glad you’re back,” she said.

“Me too,” he said. “Now he’s probably going to have you steal so watch for the signs.”

“Oh, I’m going to steal.”

Em walked back to the bag and watched for the sign. But it was a joke—there’s no stealing in softball, the base paths are too short. No, the runner must keep her foot on the bag until the ball is hit.

“She’s going!” Coach yelled.

The pitcher didn’t throw to first because they don’t do that in softball.

“She’s got a big lead!” Coach yelled.

He was being obnoxious. The girls loved it.

Cara was batting second, the pitcher, imagine that.

“C’mon Cara,” Coach yelled, “knock her block off.”

“Let’s go Cara!”

The first pitch was high, a rise ball—since they pitched underhand they could push the ball through the strike zone so that it ended up over your head. If you don’t throw those high enough they end up in the air, over the fence, and rolling for miles.

The next pitch was low and outside. 2-0.

“It’s your count!” Coach yelled.

“C’mon Cara!”

The next pitch was a mistake, right down the pipe, and Cara hit it hard, the opposite way, into right field. Em timed it perfectly (when you see them start to swing you go—yes, before contact). The ball landed in front of the right-fielder who picked it up cleanly and threw to the cut off, who relayed it to third. (Coach wished the pros would hit the cut off.)

Em rounded second and went for third. The third base coach didn’t give any sign if she should stay at second or try for third. But the throw came in high and up the line. She slid feet first.

“Safe,” the ump yelled, spreading out his arms like a plane.

Coach walked over to third. He didn’t like that no-signal. That wasn’t going to happen again. He asked Coach Thomas if he could get third. He asked, but only to be nice.

“Let me get third,” he said.

“Sure Coach.”

Coach Thomas ran across the diamond over to first.

The ump gave Coach a look.

“Sorry, Tim,” Coach said to the ump.

“Never seen that before,” Tim said.

The next batter was Missy. The sign was to hit away, but Missy didn’t give the sign to acknowledge that she received it.

“Missy,” he said.

She wiped her belt.

“C’mon kiddo.”

“Let’s take it for a ride.”

“Let’s get a run in.”

“C’mon Missy.”

Missy watched the first pitch which was a ball.

“Good eye. Good eye.”

Coach and Em were on the same base again. He told her he wanted her scoring on this one. “I want you scoring on this. On anything. You’re scoring on anything.”

“Sure am,” she said.

The next pitch Missy lofted into left field.

“Good hit, Missy,” Coach yelled. “That’s a run!” Em went back to third to tag up.

The left fielder caught the ball and threw it to the cut off.

Coach motioned for Cara to stay at second.

How hard was that?

Em jogged home. She slapped hands with the next batter, slapped hands with her teammates, and perched on the dugout fence.

She waved to her dad.

He waved back.

Damian Weber is the senior contributor to This Recording. You can download his most recent album, earnest kid, here. You can find an archive of his writing on This Recording here.

MUSIC

MUSIC  Thursday, September 21, 2017 at 8:09AM

Thursday, September 21, 2017 at 8:09AM