FILM

FILM In Which We Combine Light And Sound And Story

Wednesday, August 9, 2017 at 9:41AM

Wednesday, August 9, 2017 at 9:41AM

Dark Side of the Rainbow is Real

by DAMIAN WEBER

The 1973 album Dark Side of the Moon by Pink Floyd not only syncs with The Wizard of Oz for the first playthrough but the second and third as well, to the end of the movie. Not only is Dark Side of the Moon one of the best-selling albums ever but as a sync to The Wizard of Oz it is also a great story (the fable of you).

But this is an unpopular belief. Not many think the sync is real—almost no one. Not one of the biographies on the band. Not one book. Each of them is dismissive of the idea. Disgusted and dismissive. The band scoffs at the idea. They’ve never watched it. David Gilmour, the guitarist and singer of the band, said that the sync is a conspiracy theory from “some guy with too much time on his hands.” If they had done it, they’d have done it better. And Alan Parsons, the producer of the album, said “There simply wasn’t the mechanics to do it. We had no means of playing videotapes in the room at all. I don’t think VHS had come along by ’72, had it?”

This is disingenuous. They made many film soundtracks, and they did it the old-fashioned way — watching a print and playing along to it. In many ways, being one of the most popular rock bands in Britain, with the full support of your label, at the best recording studio in the world, working with a team of the best engineers, would make up for not having a VHS or a computer. In many ways. The Floyd’s first album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967), was recorded at EMI’s Abbey Road and their producer was Norman Smith, who was the Beatles’ producer. The only reason he wasn’t producing the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) was because he was stuck working on the Floyd album. Sgt. Pepper’s is commonly regarded as the first concept album. Dark Side of the Moon is commonly regarded as the best.

Light and Sound

Their shows in London 1967 were “happenings,” with the most important thing being the light show — even more important than their 15-minute songs. Even as early as 1967 they had movies projected during their shows. This experimentation was in place from the beginning, during their first practices, before their first shows.

“Word spread on the bush telegraph that something new and exciting was happening in Notting Hill and after only a few appearances by the band the hall was packed to capacity.” (Povey pg. 33) Joe Boyd said about the UFO Club, where the Floyd were the house band, “The object of the club is to provide a place for experimental pop music and also for mixing of medias, light shows and theatrical happenings.” (Miles, Barry. Pink Floyd: The Early Years. pg. 76)

“In addition to the bands, there was always a feature film—often a Marilyn Monroe classic or Charlie Chaplin—and other, more experimental films screened by the London Filmmakers Co-op such as films by Kenneth Anger, Andy Warhol from the New York Cinematheque or Anthony Balch and William Burroughs’ Tower Open Fire. UFO was known for its light shows which were not only directed at the band, but at all the walls and ceiling to provide a total environment. Sometimes the films were used as a part of multi-media events, such as the time when a modern jazz combo improvised to old black and white Pathé newsreels.” (Miles, pg. 77)

Soundtracks

If we ignore that they were a psychedelic band begun with the purpose of experimenting with light and sound, we can dismiss their use of multi-media and their work on soundtracks — More (1968), Zabriskie Point (1970), Obscured by Clouds (1972). Barbet Schroeder, the director of More, said “I was a big fan of the first two Floyd records. I thought they were the most extraordinary things I’d ever heard, and just wanted to work with them. I went to London and took a print of the movie More, and showed it to them. I didn’t want typical film music—made to the minute and recorded with the image on the big screen. I didn’t believe in film music.” (Blake, Mark. Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd. pg. 132)

Schroeder said, “I remember this incredibly hectic two weeks. The sound engineer couldn’t believe the speed and the creativity of the enterprise." They were able to make a soundtrack to a movie in less than two weeks and knock the socks off everyone with their creativity, professionalism, and efficiency—five years before making Dark Side of the Moon.

They did another soundtrack when Michelangelo Antonioni asked them to write songs for Zabriskie Point. The band were paid to live in Rome and work personally with the director. Only three songs were chosen for the movie and “of the Floyd pieces overlooked by Antonioni for inclusion was Rick Wright’s haunting piano-led ‘Violent Sequence,’ recorded to accompany footage of real-life student riots, which would later appear as ‘Us and Them’ on Dark Side of the Moon. But Antonioni didn’t use it — “Too sad, it makes me think of church!” In the sync this song is played when the four friends walk down the long hall leading to the Wizard of Oz with reverence and fear, like they are in basilica or going to meet a god.

Speak to Me / Breathe

The sync starts on the third roar of the MGM lion—that’s when you drop the needle. The album starts with silence. At 15 seconds we can hear a quiet heartbeat, which is all we can hear for the first 45 seconds. This interlude is called “Speak to Me” and gets us past the credits and to the start of the movie. The movie starts with the start of “Breathe.”

Breathe, breathe in the air/don't be afraid to care

Leave but don't leave me/look around, choose your own ground

For long you live and high you fly/and smiles you'll give and tears you'll cry

And all you touch and all you see/is all your life will ever be

The second time through the album, “Breathe” syncs with the Tin Man’s dance, leaning from one side all the way to the other (to a slide guitar). The third time through, the Wizard is giving advice to the four friends, much like the advice from the lyrics. But the best hits on “Breathe” are from the first time through, with Dorothy on the farm. But I’ll spare you.

The album is structured strangely — it starts with a lot of silence and ends with a lot of silence. The heartbeat starts it and ends it, as if the album is in the round, never to stop. What album does that? What suite of music? What concept album? The album is structured strangely—“Breathe” is on the album three times—once again in “Breathe (Reprise)” and again in “Any Colour You Like (Second Reprise).” The album is structured strangely — it is almost half interludes.

The Great Gig in the Sky

The sync to “The Great Gig in the Sky” starts with soft piano as Dorothy runs home to the farm, the twister starting. Then the song reaches its peak as the house is flying through the air, matching the vocalizations by Clare Torry. The song calms down as the house lands and Dorothy goes to open the door. It’s a set piece, contained in the boundaries of the scene.

Rick Wright, who wrote the song, said “The band basically wanted another four, five minutes of music. And we thought it could be an instrumental.” That’s a funny way of asking your piano player for a song. Not “Do you have any songs you want to put on the album?” But “Could you give us a sad piano song longer than four minutes but not longer than five?”

Clare Torry said, “They explained the album was about birth and all the shit you go through in your life and death. I did think it was rather pretentious. Of course, I didn’t tell them that, and I’ve since eaten my words. I think it’s a marvelous album." So when Roger later says, as he does now, that it is about life in rock ‘n’ roll, he is covering his tracks. To put us off the scent. No, the album is about becoming a more fully realized human being. We have his own words to use against him.

Money

There are 16 seconds between the last note of “The Great Gig in the Sky” and the first cha-ching of “Money,” which gives the viewer plenty of time to flip the record and put the needle on the other side. “Money” starts when Dorothy opens the door to Oz, when the movie goes from black and white to color. It’s the best sync ever, never to be topped again. We see the green of Oz and the gold of the yellow brick road as the cash registers cha-ching. It makes it seem like she’s in the money. Like she won the lotto. Then she starts walking around Munchkinland to the walking bassline of the song — a skipping 7/4.

The second time through the album, the song “Money” starts when the Wicked Witch of the West writes in the sky “Surrender Dorothy.” It feels like the citizens of the Emerald City could turn her in for the reward. Then the Lion sings about how if he were king of the forest his robes would be satin, not cotton. He’s so full of himself, he’s acting out the lyrics to “Money.”

Don’t give me that do goody good bullshit

I’m in the high-fidelity, first-class travelling set

I think I need a Learjet

Ballet Marseille

Before recording Dark Side of the Moon, the band performed live to a ballet in Marseille, France. They collaborated with the choreographer Roland Petit to make music for a dance production of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Could you get more arty?

Nick Mason said, “Playing live means that we’ve got to be note-perfect each night, otherwise the dancers are going to get lost, and we won’t be using a score, we’ll be playing from memory. That might be a bit difficult” (Povey, Glenn. Echoes: The Complete History of Pink Floyd. pg. 159). “The thing to do is to really move people. To turn them on, to subject them to a fantastic experience, to do something to stretch their imagination” (Povey, pg. 159). This from Nick Mason, who is the most dismissive of the sync.

The band were elevated above the dancers. One time, during one of the songs, the band kept playing after the dancers stopped, leaving the dancers standing on the stage. From then on someone in the crew held up cue cards so the band knew which measure they were on.

Concerts

The Floyd were one of the few bands to use theater during their concerts and to project movies, images, and animation. A lot of bands used lights and colored gels, like the Velvet Underground, but nothing that added story.

The song “Echoes,” the 23-minute epic on Meddle (1971), was the turning point. The band claimed that they were searching, groping for direction, when they found it in this song. It isn’t covered up by strings and a 20-piece orchestra, like the song “Atom Heart Mother.” It uses sound effects that are eerie and minimalistic, more like a song from Dark Side of the Moon. “Echoes” was featured in the surfer documentary Crystal Voyager (1973), used in its entirety, to images of ocean waves. The band would play that scene live in concert and play the song to it. This was the direction they wanted to go—they wanted to play along to a movie, a whole movie, live in concert. No, Pink Floyd was not asked to do the soundtrack for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Yes, Stanley Kubrick wanted to use the Pink Floyd song “Atom Heart Mother” in his movie A Clockwork Orange (1971). But Kubrick wanted to shorten the song, which was understandable considering that the song was 24-minutes long. But the band said no, they wanted Kubrick to edit his movie to it. They must have had other intentions for their music if they no longer wanted their songs to appear in movies unless they were played in their entirety.

Time / Breathe (Reprise)

Why is “Breathe (Reprise)” the third song? Isn’t a reprise usually at the end of an album? Aren’t they mostly in musicals? Kind of goofy to have the reprise so soon—unless you think of the whole suite as a cycle that repeats.

“Breathe (Reprise)” comes so soon because it ends the sync, at the last scene of the movie. It proves that the album was meant to be played to the end of the movie and not stopped after the first play through. Dorothy wakes up from the dream, back in Kansas, singing “Home, home again—I like to be here when I can.”

You would think it would be difficult to have the song sync early in the movie and then again at the end of the movie, but it’s not. The song needs to start at 13:30 in order to sync the first time and then again 86 minutes later, when Dorothy wakes up. There, the album needs to be 43 minutes long. There, the structure has been created, the most important element in place. The rest can be filled in. Just because you wouldn’t use a clock to construct your rock opera, doesn’t mean anything.

Of course it goes 2.5 times—what’s the point of only watching the beginning of the movie and not seeing Dorothy get home? What’s the point of starting an adventure and not learning anything? The reason why the lyric “I thought I’d something more to say” works as the last line to “Time,” even though it is early in the album, is because it is at the end of the sync. “Time” starts with bells ringing as Miss Gulch appears, riding her bike. They wake us from the torpor of Dorothy singing “Somewhere over the Rainbow.” Miss Gulch is coming to take Toto. “That dog’s a menace to the community. I’m taking him to the sheriff and make sure he’s destroyed.” Miss Gulch rides away with Toto in her basket.

Ticking away the moments that make up the dull day

Fritter and waste the hours in an offhand way

Kicking around on a piece of ground in your hometown

Waiting for someone or something to show you the way

The lyrics refer both to the small mindedness of Dorothy, wasting her days away, and Miss Gulch for taking away Dorothy’s dog—of our own small mindedness too. But Toto jumps out of the basket, runs down the road, and jumps through the window into Dorothy’s room. “Waiting for someone or something to show you the way.” She will need to run away or they will kill her dog.

Tired of lying in the sunshine staying home to watch the rain

You are young and life is long and there is time to kill today

And then one day you find ten years have got behind you

No one told you when to run, you missed the starting gun

Brain Damage / Eclipse

"The theme of madness had now become central to the new album," Roger Waters said, "most explicit on its closing “Brain Damage” and “Eclipse.” When I say, ‘I’ll see you on the dark side of the moon,’ what I mean is, if you feel crazy that you’re the only one ... that you seem crazy cause you think everything is crazy, you’re not alone."

Syd Barrett, the original singer of the band, who went mad and was left behind (dropped from the band), wrote a song called “The Scarecrow” on their first album. It doesn’t take much to picture Roger Waters watching the Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz, thinking of his friend who fell apart. But that doesn’t mean that Dark Side of the Moon and Dark Side of the Rainbow are only, or even mainly, about a rock star going mad. That will be The Wall.

The Scarecrow dances to “Brain Damage,” skipping like a kid, falling over himself he’s so happy to be down off that pole. He wants some smarts—he doesn’t understand why a park is roped off with a sign that reads “Keep off Grass.”

The lunatic is on the grass

The lunatic is on the grass

Remembering games and daisy chains and laughs

Got to keep the loonies on the path

Then comes the title of the album.

And if the clouds bursts thunder in your ear

You shout and no one seems to hear

And if the band you’re in starts playing different tunes

I’ll see you on the dark side of the moon

The Scarecrow has something important to say—he’s using his brain. He pleads for Dorothy to understand.

And if the dam breaks open many years too soon

And if there is no room upon the hill

And if your head explodes with dark forebodings too

I'll see you on the dark side of the moon

The song “Eclipse” isn’t separate from “Brain Damage,” it’s more like an extra chorus, an outro—to the whole suite. Being the last song, it brings all the parts together. It adds its meaning to the other songs, making all of the songs about it. It wraps around to the first song.

All you touch and all you see is all your life will ever be

The Wall

But the best evidence that Dark Side of the Rainbow is real is that they made The Wall (1979). They had finally achieved what they were working toward—with The Wall they had combined light and sound and story into a concert. They didn’t need to do soundtracks anymore, or give their songs to directors, or do surfer documentaries and ballets. No more Kubricks cutting up their songs, no more Antonionis saying their songs were too sad. Now they owned the visuals. Now they made the movies.

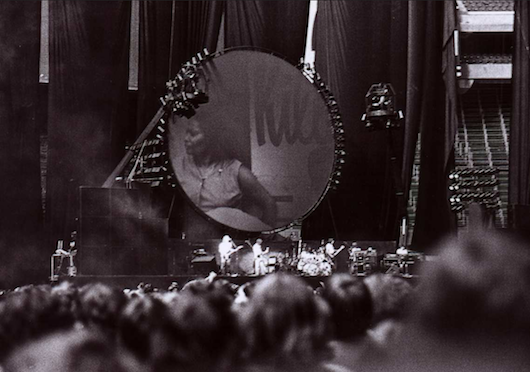

“The concerts remain the most spectacular ever staged by a rock band. As they played, a wall of cardboard bricks was built across the stage in front of them, meaning that they performed half of the show hidden from view. The wall doubled as a screen, onto which were projected images, including Scarfe’s animations.... The stage was also shared with forty-foot high puppets. Owing to the complexity and cost of the stage show, The Wall was performed in only four cities” (Mabbett, Andy. Pink Floyd: The Music and the Mystery. pgs. 80-81).

Why is it hard to believe that the band that made the greatest rock movie, The Wall (1982), wouldn’t have tried it first with an old movie? If anyone were to have done it, wouldn’t it have been them?

But what doesn’t make sense is that the band never watched it. Why not say, “Isn’t it pretty neat how it makes the story of Dorothy the story of you?” It’s not because they are too busy, it’s because they are flatly denying it. They say that it wasn’t possible, that the fans have too much time on their hands, too many drugs. But that rings hollow because it was possible and the only ones with too much time on their hands was your druggy band.

Damian Weber is the senior contributor to This Recording. You can find an archive of his writing in these pages here.

damian weber,

damian weber,  pink floyd

pink floyd