POETRY

POETRY In Which He Could Visit Her And Did Not Need To Write

Monday, November 26, 2012 at 11:05AM

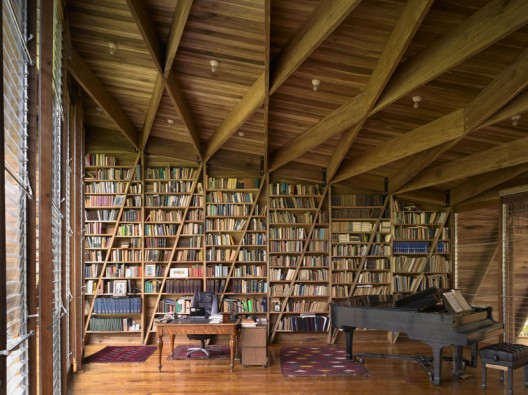

Monday, November 26, 2012 at 11:05AM  ted berrigan by alex katz

ted berrigan by alex katz

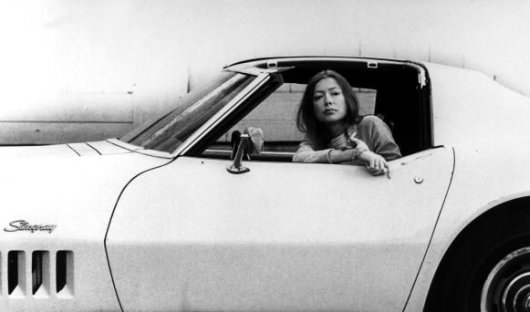

Ted and Sandy

by DAMIAN WEBER

Ted Berrigan met Sandy Alper and seven days later they were married. She wrestled him to the ground, sat on his lap, and asked him to marry her. He agreed. She dropped out of college and boarded a bus with him to Houston, where she pawned her watch to pay for the marriage license. She said she dropped out of college because she could tell, in an instant, that “living with Ted would be far more educational than staying in school."

Sandy writes in the introduction,

I lugged a big suitcase out of the dorm, announcing that I was taking some props to the drama department, and we got a bus to Houston. We could stay with Ted’s friend there, Marge Kepler. In Houston we had a blood test and I pawned my watch to pay for the marriage license. We bought Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind as a wedding gift to ourselves. That afternoon we made love (I for the first time), in Marge’s bed. It turned out that she had been his lover in Tulsa. Later the three of us had to sleep together because there was only one bed in the house.

The letters between Ted Berrigan and Sandy Alper were published for the first time in Dear Sandy, Hello. In it Sandy explains that she was young (19) but she knew what she was doing. Once married, they visited her parents in Miami, who searched Ted's things and found letters from Ron Padgett about the drug scene on the Columbia campus. The next day the police arrived to take Sandy to Jackson Memorial Hospital mental ward.

Ted writes,

Sandy, get out of that place. If it takes a month, a year, years, get out of there. Lie, steal, cheat, do anything, but get out and come to me. I will be trying every way I know how to get you free. But they have us where they want, they think. I am sure they are going to have this marriage annulled. They are going to find you “disturbed,” and have the marriage set aside. Well, we don’t need to care about that. Our marriage can’t be set aside, no matter what legal authorities say. What is important is that we be together again. We can’t fight them their way. What we have to do is do anything they say, resisting only when we feel we have to. Don’t sign anything. We’ll do what they say, but when their backs are turned, we’ll be gone.

Come here any way you know how. If you think I can help by coming there, tell me, and I’ll hitchhike there tomorrow. Once we are together, we’ll vanish from their sight until such time as they recognize our love, our marriage, our dignity as human beings. Honey, don’t ever let them make you think you are sick, or disturbed, or anything of the kind. We are all sick, and disturbed, but if you ever believed anything I said, believe me when I say that you are the best, the healthiest, the most good of all of us.

She writes,

I found something about love life in The Brothers K. I am going to show it to the next doctor. Maybe he will see that I am not going to destroy myself and you aren’t. I seem to be struggling for both of us instead of just me. You will be part of my whole self forever.

I think I would like to read more Ibsen.

I talked to the Negro maid today. She is a great lady. She ran away with her first husband at the age of twelve and was married to him for twenty-seven years. He then died. She is good. She thinks the whole business is silly. I wish you could meet her. I wish you could be here. These people need much hope. You show people that sometimes dreams do come true if the dreamer works hard and believes. If he has faith and courage.

She writes,

They are putting the annulment papers in tomorrow. I asked them if they would harm you if you came down, and my father said he might even try to kill you if he saw you or lock you up. The doctor has recommended treatment with an analyst or psychiatrist and I would live at home. They have accused you of much. Mainly of being schizophrenic and not realizing it or trying to do anything about it. Also you are a moocher and live off of others; Anne, Pat, Margie, your mother. They have evidence, letters etc. and what they have said about you. They also said you were not given your master’s degree, not even awarded it, but your letter of non-acceptance was a front and so many more things.

I wish you would write a letter telling me about all the truth about you. No matter how bad you may think it may be. Ted, even though I believe in you and your love for me, they have created doubts. I am not even sure I will believe either of you.

I do believe your love and many of the things you have said to me because I have seen myself the truth in life and the communication we have had is real.

march 1962

march 1962

Ted responds,

My darling Sandy, I don’t know where to begin this letter. Are we losing? Are they coming between us? Honey, I love you so very very much. I want to answer all your questions very carefully. I want to tell you everything, give you everything you ever want to ask of me.

But forgive me, I must talk a little first.

Sandy, they’re beating us. They’re getting us down. All this about the annulment, and the detective reports, is something we knew from the first. I told you that this is exactly what they would do. Their plan is to separate us, to annul the marriage, and to use your sympathies and your natural feelings for your parents to drive doubts between us like a wedge until finally we are apart for good.

I beg you, I beg you again, don’t defend me. Not to them, not to doctors, not to other patients, not even to yourself. Remember how it was when we were together, remember how I look and seem to you. Remember the love we have for each other. Have faith in your judgment, your feelings, yourself, in me. If you try to argue with their ideas about me, their supposed “facts,” you cannot win. Their logic is superior to yours, and mine, their age and experience and their determination are something you cannot cope with by fighting them according to their rules. They know how to handle you. In only five weeks they have gotten you to write a line to me which reads “I am not sure I will believe either of you,” meaning them or me. What will they accomplish in another five weeks? or ten? or fifty?

Honey, I haven’t heard one word from your parents. I have received no legal notice from anyone. What right do they have to decide whether it is all right for you and me to be married? We must not allow them to even question us except as equals. We cannot act like all they want is what is best for you, when they have locked you up. It seems that all they want is what they say is best for you.

Sandy, don’t forget that Sunday night in Miami. Don’t forget your mother asking if you wanted to use her leather coat in New York, your mother and father handing you over to strangers. Don’t forget.”

Ted goes on to admit every weird or incriminating thing he ever did. He was completely honest, and that section of Dear Sandy, Hello reads like an autobiography. She believed him, she believed in him again.

There was a boy in the ward with Sandy who was disparaging of Ted, and whom she grew to dislike. He was also a writer, but didn’t like beatniks, and became convinced Ted was one.

I just met the new male patient. He is a writer from New York by the name of Barry Weiss. He doesn’t know you or Joe. He lived on 11th street. He doesn’t like poetry much and is very wary of your type, he says. He is cynical. He loves Henry Miller and says he can only read 25 or fewer pages at a time and then he must stop. He has sad eyes. Things writers can only write in aloneness and desolation.

On a different day she writes,

Barry talked to me a little, he thinks perhaps you are just an ordinary beatnik. He doesn’t know you. I wish you could give him a good working over. Send me Tropic of Cancer if you can. Barry did give me some candy and apricots so I can’t hate him. He has a few good qualities. He doesn’t think I have the stuff it takes.

And finally, “Barry is rotten as ever. He may leave. I hope so.” We can only speculate he was a know-it-all who knew nothing, and that Sandy didn’t like pretentious no-fun sourpusses.

They were both reading Henry Miller. She noted, “I just finished reading Tropic of Cancer, Barry loaned it to me. I did underestimate it. But still don’t think it is the greatest book. Some parts I liked a lot. I will read them again. He does have great vitality and life. It makes me want to be out even more.”

He writes, “I’m not really incoherent. I’m in a kind of trance from reading Henry Miller’s Tropic of Capricorn. It is so great I have to stop every few pages and wonder." After speaking of killing birds to eat (a fantasy) he writes:

If I killed a little bird and roasted it over the fire and ate it, it was not because I was hungry but because I wanted to know about Timbuktu or Tierra del Fuego. I had to stand in the vacant lot and eat dead birds in order to create a desire for that bright land which later I would inhabit alone and people with nostalgia. I expected ultimate things of this place, but I was deplorably deceived. I went as far as one could go in a state of complete deadness, and then by a law, which must be the law of creation, I suppose, I suddenly flared up and began to live inexhaustibly, like a star whose light is unquenchable.

Sandy, my beautiful, innocent wife, Miller has just said simply much of what I have been struggling to tell you. If I eat dead birds in vacant lots, it is not because I am hungry, but because I need to discover Tierra del Fuego, the land of fire, the fiery earth. I people my poems with nostalgia. They are in part my bright land. And through the past few months, and most of all through my loving you, through marrying my soul, my self to yours as was preordained, I have now flared up like a burning rose, like a dove, and begun to live inexhaustibly, like a star whose light is unquenchable, good to eat a thousand years.

On a different day Ted writes,

I finished Henry Miller’s book called Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch today, and it really was a good book. Miller continually fills me with the joy of life. Right now I am living like the fox lives. All my senses have become sharper, and I smell, see, taste, and hear much more acutely than before. Food tastes marvelous, because we eat little. The weather is simply exciting all the time. We walk up and down all the streets. And all the time I think of you. I want so much to touch you, to lie with my eyes closed and feel you watching me. I do love you so.

Sandy writes,

I am entranced by Miller. Entranced and re-injected with faith. He is great. Your letter was sad because I want so much for you to be writing but I can’t do much now. I certainly don’t want you to be locked up or anything. It doesn’t torture me too much that you are out and free...

I have started reading Big Sur. It is great. I do have faith and courage. We too someday will be able to live our life. This book so far isn’t as wild that’s why it’s easier for me to take. Anyway he was a lot older. Life gets quieter after 50 or 60 I guess.

They exchanged ideas. They listed the books they were reading at the time, and what they thought. No slouch, Sandy was reading the best books, and open to suggestions from Ted, Joe Brainard, Dick Gallop, and Ron Padgett — a fine group of instructors.

He writes,

I have some new good books of poetry, and I’m reading a lot, not writing too much, except for the series I’m doing with Joe. I’ve read Go, a novel by Clellon Holmes about New York in the 50s, finished Henry Miller’s the Tropic of Capricorn, read a lot of poetry by a lot of people, and am now reading Frederico Garcia Lorca’s Poet in New York, and the selected poems of Vladimir Mayakofsky, the young Russian poet. Dick has finished a book by William Styron called Lie Down in Darkness, and is reading Styron’s second novel, Set This House on Fire. Styron is a young Southern writer, and he is very very good. Both these books are as good novels as have been done in America since A Farewell to Arms.”

His letters read like his poems.

Joe is sitting over on his bed writing a postcard to you. My fingers are sore from pounding the typewriter. When I first get up my hands are not as loose as later in the day, and I miss the keys sometimes and bang up my fingers. We are making hot coffee now, and preparing to work on our collages some more. We’re still working on our religious one, although Joe has done two of his own, without writing, since I wrote yesterday. So, Dick and I are walking the streets, waiting for his check, and reading our books. I’m reading Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch by Henry Miller and Dick is reading The Tropic of Capricorn. I want to send this (my) book to you as soon as I finish.

She writes back,

I finished Daring Young Man. I am going to read some parts again. Oh! To be with you. Someday I would like to meet Saroyan. I will hope you will not be mad but I started Rebecca by Du Maurier. She reminds me of Conrad only not so intense. Her books so far is atmosphere. The second wife is painful in her ineptitude and shyness although I am sure she is a good soul. I want to finish it so that I can start Bread and Wine....

I read “Kaddish” and “Howl” and “Thank You” and “Fresh Air” and scattered other poems today. Nothing else. I have so much nervous energy. I don’t know what to do. Oh Ted just to walk the streets with you would be enough, to talk to you and hold your hand....

I read Lorca every day. He is good — sounds beautiful — very simple, lyric, and clear. Have been reading in the New Yorker about a beautiful grand modern cathedral. We must remember it in case we ever go to Europe.

He writes, “I’m reading Henry Miller (Tropic of Capricorn), poems by John Ashbery, Joe’s notebooks, and a novel by a writer named Clellon Holmes called Go. Dick is reading the newest book on the pre-Socratics, Tom is reading a book by Edward Dahlberg (who wrote the poem Dave said is very great, remember). Tom and I wrote a collaboration today called 'O’Hara’s Sources.' It’s a fourteen-line poem using ground rules.”

Ted was working on his translation of Arthur Rimbaud’s The Drunken Boat, which wasn’t a literal translation, but instead an homage. She mailed to him to say,

Read “The Drunken Boat” again and I like it of course I can’t be too critical of it as a free translation because I can’t read French. I’ll read it again tomorrow. I like the “Spooky Winds” especially where you put it. The last two stanzas seem much different than the other—tone I guess.

Later she says,

I read the revision of “The Drunken Boat.” I feel so good that you dedicated it to me. I wish you were here so you could explain the various changes. Some of them affect the flow and rhythm and style a lot. Later we can do it. Many of the good parts you left the same. I am going to read them a few more times.

And finally,

I went carefully over “The Drunken Boat” the final version is more idiomatic and modern and concise—less 19th-century I guess. We can talk about the fine details later. I think it’s good to know the reason for picking certain words over others in translation. Some sound better but there must be other reasons.

Ron Padgett insists that Berrigan’s The Sonnets were written by having Sandy pick her favorite lines, which he then arranged randomly based on their sound rather than their meaning. In his writing about his friend, Padgett explains that it was a long growing process for Ted to outgrow formalism and become loose. Ted says of The Sonnets, “Wrote by ear, and automatically. Very interesting results....All of this partly inspired by reading about DADA but mostly inspired by my activities along the same line for the past 10 months...working on collages with Joe."

"Ted," Padgett says, "with Sandy’s help, had set in motion the creative machine he had been assembling over the past two years, the machine that would enable him to create a 'big' work."

The letters span two months and end when Ted went down to Miami to rescue Sandy. She received permission from her doctor to go to the local library. It was her first time out of the hospital and she used it immediately to meet up with Ted. (Many of their letters back and forth contained secret plans for what to do if she escaped, but there was no mention of this attempt.) They hitched to Denver, then decided to head back to New York. They settld near Columbia University. She learned to shoplift and wrote a friend about it, who showed her mom, who showed Sandy’s mom. Her parents hired a private detective, again, to get dirt on Ted, and to find out where they were.

Again, Sandy was committed to a mental hospital, this time Bellevue in Manhattan. None of the letters are from this period — maybe he could visit her, and didn’t need to write. There was a little poem he scribbled then: “I never thought . . . / that I’d come so much to Brooklyn / just to see lawyers and cops who don’t even carry / guns taking my wife away and bringing her back.” Then a judge freed her, and her parents gave up pursuit.

Damian Weber is the senior contributor to This Recording. He is a writer living in Brooklyn. You can find an archive of his writing on This Recording here. He last wrote in these pages about the flies. You can find more of his writing here.

"See No Green" - Race Horses (mp3)

"My Year Abroad" - Race Horses (mp3)

with anne waldman

with anne waldman

damian weber,

damian weber,  ted berrigan

ted berrigan