BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Get Down To The Actual Writing

Friday, November 4, 2011 at 11:29AM

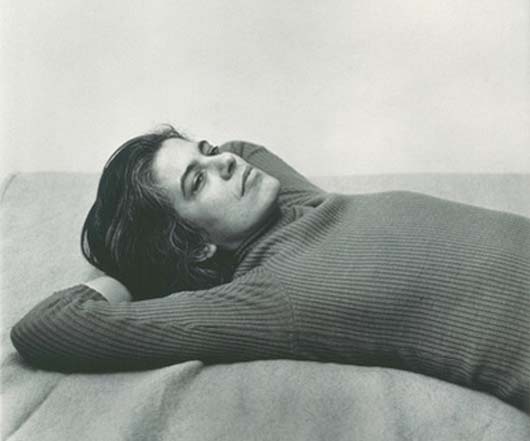

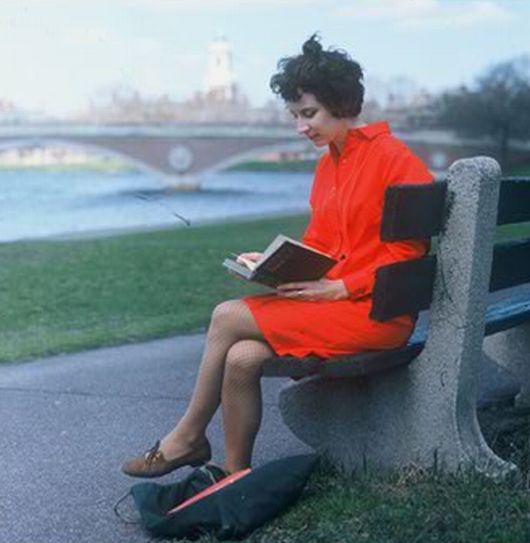

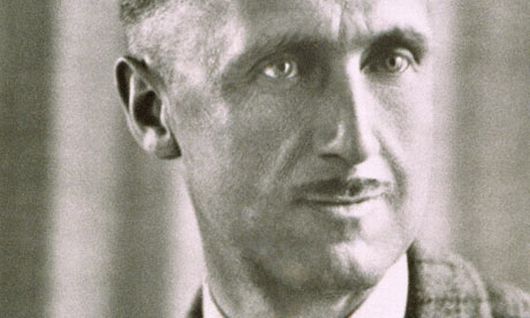

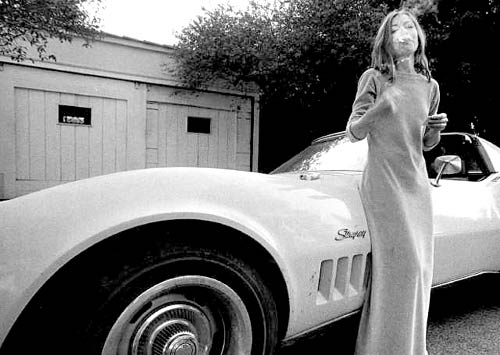

Friday, November 4, 2011 at 11:29AM  margaret atwood in cambridge, 1963

margaret atwood in cambridge, 1963

How and Why to Write

The best writing advice contradicts itself, because there are not a finite number of ways to create a masterpiece. Advice about writing is more importantly writing itself, and it defines its own rules and strictures as much as it instructs its adherents directly. In the words of these masters we find the strength to go on.

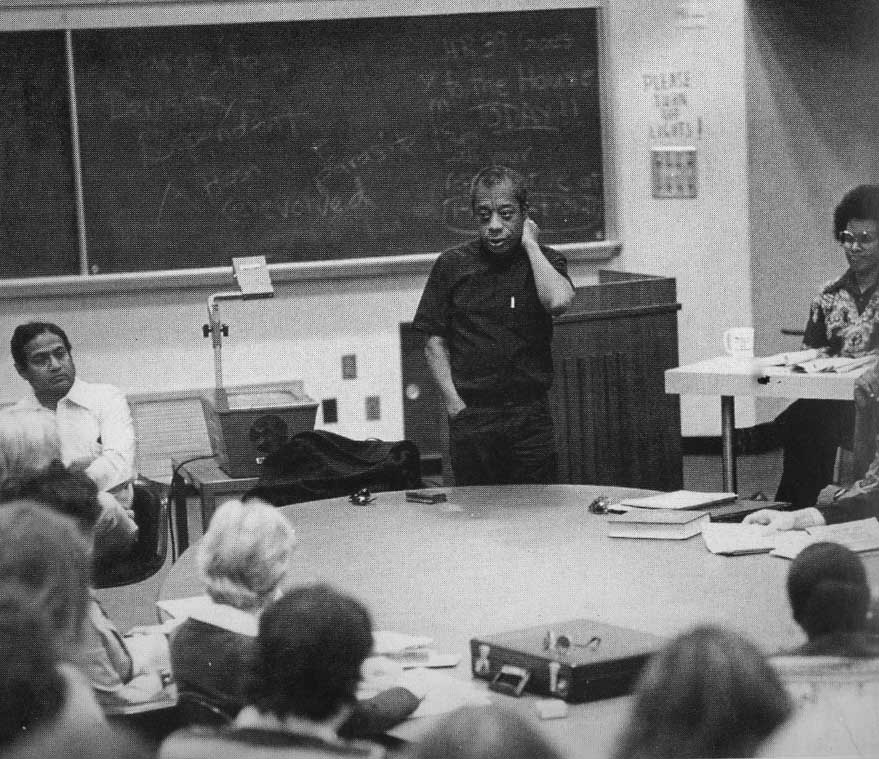

James Baldwin

I don't know if I feel close to them, now. After a time you find, however, that your characters are lost to you, making it quite impossible for you to judge them. When you've finished a novel it means, "The train stops here, you have to get off here." You never get the book you wanted, you settle for the book you get. I've always felt that when a book ended there was something I didn't see, and usually when I remark the discovery it's too late to do anything about it.

It happens when you are right here at the table. The publication date is something else again. It's out of your hands, then. What happens here is that you realize that if you try to redo something, you may wreck everything else. But, if a book has brought you from one place to another, so that you see something you didn't see before, you've arrived at another point. This then is one's consolation, and you know that you must now proceed elsewhere.

Henry Miller

Henry Miller

Sometimes I would sit at the machine for hours without writing a line. Fired by an idea, often an irrelevant one, my thoughts would come too fast to be transcribed. I would be dragged along at a gallop, like a stricken warrior tied to his chariot.

On the wall at my right there were all sorts of memoranda tacked up: a long list of words, words that bewitched me and which I intended to drag in by the scalp if necessary; reproductions of paintings, by Uccello, della Francesca, Breughel, Giotto, Memling; titles of books from which I meant to deftly lift passages; phrases filched from my favorite authors, not to quote but to remind me how to twist things occasionally; for example: "The worm that would gnaw her bladder" or "the pulp which had glutinized behind his forehead." In the Bible were slips of paper to indicate where gems were to be found. The Bible was a veritable diamond mine. Every time I looked up a passage I became intoxicated. In the dictionary were place marks for lists of kind or another; flowers, birds, trees, reptiles, gems, poisons, and so on. In short, I had fortified myself with a complete arsenal.

But what was the result? Pondering over a word like praxis, for example, or pleroma, my mind would wander like a drunken wasp.

Toni Morrison

Very, very early in the morning, before they got up. I'm not very good at night. I don't generate much. But I'm a very early riser, so I did that, and I did it on weekends. In the summers, the kids would go to my parents in Ohio, where my sister lives - my whole family lives out there — so the whole summer was devoted to writing.

And that's how I got it done. It seems a little frenetic now, but when I think about the lives normal women live — of doing several things — it's the same. They do anything that they can. They organize it. And you learn how to use time. You don't have to learn how to wash the dishes every time you do that. You already know how to do that. So, while you're doing that, you're thinking. You know, it doesn't take up your whole mind. Or just on the subway. I would solve a lot of literary problems just thinking about a character in that packed train, where you can't do anything anyway. Well, you can read the paper, but you're sort of in there.

And then I would think about, well, would she do this? And then sometimes I'd really get something good. By the time I'd arrived at work, I would jot it down so I wouldn't forget. It was a very strong interior life that I developed for the characters, and for myself, because something was always churning. There was no blank time. I don't have to do that anymore. But still, I'm involved in a lot of things, I mean, I don't go out very much.

Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

I guarantee you that no modern story scheme, even plotlessness, will give a reader genuine satisfaction, unless one of those old fashioned plots is smuggled in somewhere. I don't praise plots as accurate representations of life, but as ways to keep readers reading. When I used to teach creative writing, I would tell students to make their characters want something right away — even if it's only a glass of water. Characters paralyzed by the meaninglessness of modern life still have to drink water from time to time.

One of my students wrote a story about a nun who got a piece of dental floss stuck between her lower left molars, and who couldn't get it out all day long. I thought that was wonderful. The story dealt with issues a lot more important than dental floss, but what kept readers going was anxiety about when the dental floss would finally be removed. Nobody could read that story without fishing around in his mouth with a finger.

When you exclude plot, when you exclude anyone's wanting anything, you exclude the reader, which is a mean-spirited thing to do. You can also exclude the reader by not telling him immediately where the story is taking place, and who the people are. It's the writer's job to stage confrontations, so the characters will say surprising and revealing things, and educate and entertain us all. If a writer can't or won't do that, he should withdraw from the trade.

Margaret Atwood

1 Take a pencil to write with on aeroplanes. Pens leak. But if the pencil breaks, you can't sharpen it on the plane, because you can't take knives with you. Therefore: take two pencils.

2 If both pencils break, you can do a rough sharpening job with a nail file of the metal or glass type.

3 Take something to write on. Paper is good. In a pinch, pieces of wood or your arm will do.

4 If you're using a computer, always safeguard new text with a memory stick.

5 Do back exercises. Pain is distracting.

6 Hold the reader's attention. (This is likely to work better if you can hold your own.) But you don't know who the reader is, so it's like shooting fish with a slingshot in the dark. What fascinates A will bore the pants off B.

7 You most likely need a thesaurus, a rudimentary grammar book, and a grip on reality. This latter means: there's no free lunch. Writing is work. It's also gambling. You don't get a pension plan. Other people can help you a bit, but essentially you're on your own. Nobody is making you do this: you chose it, so don't whine.

8 You can never read your own book with the innocent anticipation that comes with that first delicious page of a new book, because you wrote the thing. You've been backstage. You've seen how the rabbits were smuggled into the hat. Therefore ask a reading friend or two to look at it before you give it to anyone in the publishing business. This friend should not be someone with whom you have a romantic relationship, unless you want to break up.

9 Don't sit down in the middle of the woods. If you're lost in the plot or blocked, retrace your steps to where you went wrong. Then take the other road. And/or change the person. Change the tense. Change the opening page.

10 Prayer might work. Or reading something else. Or a constant visualisation of the holy grail that is the finished, published version of your resplendent book.

Gertrude Stein

You can tell that so well in the difficulty of writing novels or poetry these days. The tradition has always been that you may more or less describe the things that happen you imagine them of course but you more or less describe the things that happen but nowadays everybody all day long knows what is happening and so what is happening is not really interesting, one knows it by radios cinemas newspapers biographies autobiographies until what is happening does not really thrill any one, it excited them a little bit but does not really thrill them.

The painter can no longer say that what he does is as the world looks to him because he cannot look at the world anymore, it has been photographed too much and he has to say that he does something else. In former times a painter said he painted what he saw of course he didn't but anyway he could say it, now he does not want to say it because seeing it is not interesting.

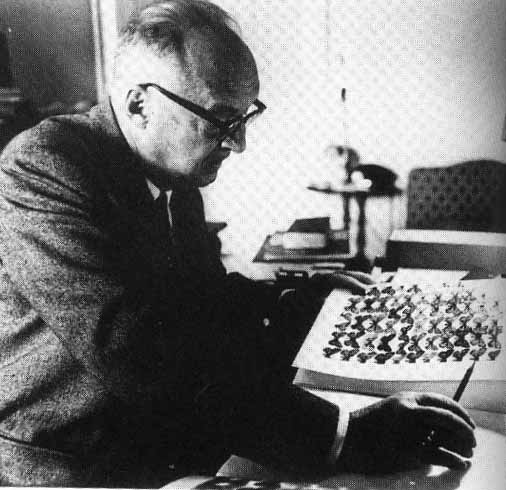

Vladimir Nabokov

The force and originality involved in the primary spasm of inspiration is directly proportional to the worth of the book the author will write. At the bottom of the scale a very mild kind of thrill can be experienced by a minor writer, noticing, say, the inner connection between a smoking factory chimney, a stunted lilac bush in the yard, and a pale-faced child; but the combination is so simple, the threefold symbol so obvious, the bridge between the images so well-worn by the feet of literary pilgrims and by cartloads of standard ideas, and the world deduced so very like the average one, that the work of fiction set into motion will be necessarily of modest worth.

On the other hand, I would not like to suggest that the initial urge with great writing is always the product of something seen or heard or smelt or tasted or touched during a long-haired art-for-artist's aimless rambles.

Although to develop in one's self the art of forming sudden harmonious patterns out of widely separate threads is never to be despised, and although, as in Marcel Proust's case, the actual idea of a novel may spring from such actual sensations as the melting of a biscuit on the tongue or the roughness of a pavement underfoot, it would be rash to conclude that the creation of all novels ought to be based on a kind of glorified physical experience. The initial urge may disclose as many aspects as there are temperaments and talents; it may be the accumulated series of several practically unconscious shocks or it may be an inspired combination of several abstract ideas without a definite physical background.

But in one way or another the process may still be reduced to the most natural form of creative thrill — a sudden, live image constructed in a flash out of dissimilar units which are apprehended all at once in a stellar explosion of the mind.

W. Somerset Maugham

All I can usefully do is to tell you what is my own practice, and the first thing that strikes me that I have no habitual practice; it seems to me that every novel must be written in an entirely different fashion, and so far as I am concerned each one is in a way no more than an experiment. Each subject needs a different treatment, a different attitude, and even a different manner of writing. The only rule I know which is always valid is to stick to your point like grim death.

I cannot help thinking that to entertain is sufficient ambition for the novelist, and it is certainly one which is hard to achieve; if he can tell a good story and create characters that are fresh and living he has done enough to make the reader grateful. You will not have failed to notice that many novels are written which have every possible excellence and yet are quite unreadable. I hope you will not think it a willful eccentricity when I tell you that I look upon readableness as the highest merit that a novel can have. They say it is better for women to be than to be clever; that is a point upon which I have never been able to make up my mind; but I am quite sure that it is better for a novel to be readable than to be good and clever. I have often wondered what exactly it is that gives a book this quality. I will not tell you all the conclusions I have come to but only one or two points which seem to me to tend to that admirable result.

I think first of all that the writer is wise to be brief. The value of a piece of fiction depends in the final analysis on the personality of the author. If it is interesting, he will interest. It is true that the young writer cannot expect to have a personality that is either complex or profound; personality grows with the experiences of life; but he has some counterbalancing advantages. He sees things, the environment in which he has grown up, with the freshness and energy of his youth; he knows the persons of his own family and the persons with whom his daily life since childhood has brought him in contact, with an intimacy he can seldom hope to have with people he comes to know in later years. Here is material ready to his hand. If his personality is so commonplace that he can see this environment and these people only in commonplace way, then he is not made to be a writer, and he is only wasting his time in trying.

Langston Hughes

How to be a bad writer (in ten easy lessons):

1. Use all the clichés possible, such as "He had a gleam in his eye," or 'Her teeth were white as pearls."

2. If you are a Negro, try very hard to write with an eye dead on the white market - use modern stereotypes of older stereotypes - big burly Negroes, criminals, low-lifers, and prostitutes.

3. Put in a lot of profanity and as many pages as possible of near pornography and you will be so modern you pre-date Pompeii in your lonely crusade toward the bestseller lists. By all means be misunderstood, unappreciated, and ahead of your time in print and out, then you can be felt-sorry-for by your own self, if not the public.

4. Never characterize characters. Just name them and then let them go for themselves. Let all of them talk the same way. If the reader hasn't imagination enough to make something out of cardboard cut-outs, shame on him!

5. Write about China, Greence, Tibet or the Argentine pampas — anyplace you've never seen and know nothing about. Never write about anything you know, your home town, or your home folks, or yourself.

6. Have nothing to say, but use a great many words, particularly high-sounding words, to say it.

7. If a playwright, put into your script a lot of hand-waving and spirituals, preferably the ones everybody has heard a thousand times from Marion Anderson to the Golden Gates.

8. If a poet, rhyme June with moon as often and in as many ways as possible. Also use thee's and thou's and 'tis and o'er , and invert your sentences all the time. Never say, "The sun rose, bright and shining." But rather, "Bright and shining rose the sun.'

9. Pay no attention really to the spelling or grammar or the neatness of the manuscript. And in writing letters, never sign your name so anyone can read it. A rapid scrawl will better indicate how important and how busy you are.

10. Drink as much liquor as possible and always write under the presence of alcohol. When you can't afford alcohol yourself, or even if you can, drink on your friends, fans, and the general public.

If you are white, there are many more things I can advise in order to be a bad writer, but since this piece is for colored writers, there are some thing I know a Negro just will not do, not even for writing's sake, so there is no use mentioning them.

Marguerite Duras

It's uncomfortable sitting at a round table: your elbows aren't resting on anything and you can't lean on them to rest from writing, and while you're writing they're sticking out into nowhere, and if you don't notice that right away you tell yourself, "I don't know what's wrong with me, I'm tired," and it's because your elbows aren't resting on the table.

George Orwell

Putting aside the need to earn a living, I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living. They are:

(i) Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on the grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful businessmen — in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all — and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.

(iii) Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

(iv) Political purpose. Using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other peoples’ idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

It can be seen how these various impulses must war against one another, and how they must fluctuate from person to person and from time to time.

John Ashbery

Every writer faces the problem of the person that he is writing for, and I think nobody has ever been able to imagine satisfactorily who this “homme moyen sensuel” will be. I try to aim at as wide an audience as I can so that as many people as possible will read my poetry. Therefore I depersonalize it, but in the same way personalize it, so that a person who is going to be different from me but is also going to resemble me just because he is different from me, since we are all different from each other, can see something in it. You know — I shot an arrow into the air but I could only aim it. Often after I have given a poetry reading, people will say, “I never really got anything out of your work before, but now that I have heard you read it, I can see something in it.” I guess something about my voice and my projection of myself meshes with the poems. That is nice, but it is also rather saddening because I can't sit down with every potential reader and read aloud to him.

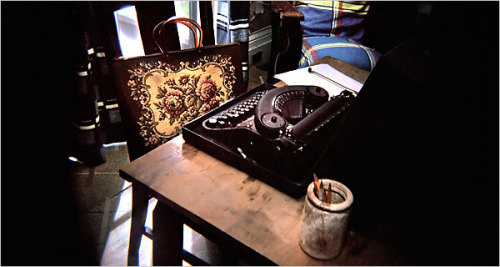

I write on the typewriter. I didn't use to, but when I was writing “The Skaters,” the lines became unmanageably long. I would forget the end of the line before I could get to it. It occurred to me that perhaps I should do this at the typewriter, because I can type faster than I can write. So I did, and that is mostly the way I have written ever since. Occasionally I write a poem in longhand to see whether I can still do it. I don't want to be forever bound to this machine.

Susan Sontag

Many writers who are no longer young claim, for various reasons, to read very little, indeed, to find reading and writing in some sense incompatible. Perhaps, for some writers, they are. It's not for me to judge. If the reason is anxiety about being influenced, then this seems to me a vain, shallow worry. If the reason is lack of time — there are only so many hours in the day, and those spent reading are evidently subtracted from those in which one could be writing — then this is an asceticism to which I don't aspire.

Losing yourself in a book, the old phrase, is not an idle fantasy but an addictive, model reality. Virginia Woolf famously said in a letter, ''Sometimes I think heaven must be one continuous unexhausted reading.'' Surely the heavenly part is that — again, Woolf's words — ''the state of reading consists in the complete elimination of the ego.'' Unfortunately, we never do lose the ego, any more than we can step over our own feet. But that disembodied rapture, reading, is trancelike enough to make us feel ego-less.

Like reading, rapturous reading, writing fiction — inhabiting other selves — feels like losing yourself, too.

Everybody likes to think now that writing is just a form of self-regard. Also called self-expression. As we're no longer supposed to be capable of authentically altruistic feelings, we're not supposed to be capable of writing about anyone but ourselves.

But that's not true.

Robert Creeley

For me, it's literally the time it takes to type or otherwise write it — because I do work in this fashion of simply sitting down and writing, usually without any process of revision. So that if it goes — or, rather, comes — in an opening way, it continues until it closes, and that's usually when I stop. It's awfully hard for me to give a sense of actual time because as I said earlier, I'm not sure of time in writing. Sometimes it seems a moment and yet it could have been half an hour or a whole afternoon. And usually poems come in clusters of three at a time or perhaps six or seven. More than one at a time. I'll come into the room and sit and begin working simply because I feel like it. I'll start writing and fooling around, like they say, and something will start to cohere; I'll begin following it as it occurs. It may lead to its own conclusion, complete its own entity. Then, very possibly because of the stimulus of that, something further will begin to come. That seems to be the way I do it. Of course, I have no idea how much time it takes to write a poem in the sense of how much time it takes to accumulate the possibilities of which the poem is the articulation.

Allen Ginsberg, for example, can write poems anywhere — trains, planes, in any public place. He isn't the least self-conscious. In fact, he seems to be stimulated by people around him. For myself, I need a very kind of secure quiet. I usually have some music playing, just because it gives me something, a kind of drone that I like, as relaxation. I remember reading that Hart Crane wrote at times to the sound of records because he liked the stimulus and this pushed him to a kind of openness that he could use. In any case, the necessary environment is that which secures the artist in the way that lets him be in the world in a most fruitful manner.

John Steinbeck

My basic rationale might be that I like to write. I feel good when I am doing it — better than when I am not. I find joy in the texture and tone and rhythms of words and sentences, and when these happily combine in a "thing" that has texture and tone and emotion and design and architecture, there comes a fine feeling — a satisfaction like that which follows good and shared love. If there have been difficulties and failures overcome, these may even add to the satisfaction.

As for my "reasoned exposition of principles," I suspect that they are no different from those of any man living out his life. Like everyone, I want to be good and strong and virtuous and wise and loved. I think that writing may be simply a method or technique for communication with other individuals; and its stimulus, the loneliness we are born to. In writing, perhaps we hope to achieve companionship. What some people find religion, a writer may find in his craft or whatever it is — absorption of the small and frightened and lonely into the whole and complete, a kind of breaking through to glory.

Flannery O'Connor

Point of view drives me crazy when I think about it but I believe that when you are writing well, you don't think about it. I seldom think about it when I am writing a short story, but on the novel it gets to be a considerable worry. There are so many parts of the novel that you have to get it over with so you can get something else to happen, etc, etc. I seem to stay in a snarl with mine.

Of course I hear the complaint over and over that there is no sense in writing about people who disgust you. I think there is; but the fact is that the people I write about certainly don't disgust me entirely though I see them from a standard of judgment from which they fall short. Your freshman who said there was something religious here was correct. I take the Dogmas of the Church literally and this, I think, is what creates what you call the "missing link." The only concern, so far as I see it, is what Tillich calls "the ultimate concern." It is what makes the stories spare and what gives them any permanent quality they may have.

I beat my brains out this morning on a story I am hacking at and in the afternoon and I am exhausted is why I haven't got down to the typewriter. It takes great energy to typewrite something. When I typewrite something the critical instinct operates automatically and that slows me down. When I write it by hand, I don't pay much attention to it....

There is really one answer to the people who complain about one's writing about "unpleasant" people — and that is that one writes what one can. Vocation implies limitation but few people realize it who don't actually practice an art.

I don't know how you would tell anybody his writing was mannered, except you say, "Brother this is mannered." I once had the sentence: "He ran through the field of dead cotton" and Allen Tate told me it was mannered; should have been "dead cotton field." I don't hold that against Allen. Give him something good to criticize and he would do better.

I hope you don't have friends who recommend Ayn Rand to you. The fiction of Ayn Rand is as low as you can get re: fiction. I hope you picked it up off the floor of the subway and threw it in the nearest garbage pail. She makes Mickey Spillane look like Dostoevsky.

Charles Baxter

In day-to-day life we play these little games of comparison-contrast in which we are usually the contrast. I wouldn't have done it that way. Look at him, now, the one who did it, sinking. At least it wasn't me! By telling stories in this manner, we become narratable. We find a story for ourselves. We spin around ourselves, in what seems to be a natural form, the cobweb of a plot. We move our own lives into the condition of narrative progression. Plot often develops out of the tensions between characters, and in order to get that tension, a writer sometimes has to be a bit of matchmaker, creating characters who counterpoint one another in ways that are fit for gossip. Our hapless friend is character, but not yet my character. With counterpointed characterization, certain kinds of people are pushed together, people who bring out a crucial response to each other. A latent energy rises to the surface, the desire or secret previously forced down into psychic obscurity.

It seeks to be in the nature of plots to bring a truth or a desire up to the light, and it has often been the task of those who write fiction to expose elements that are kept secret in a personality, so that the mask over that personality (or any system) falls either temporarily or permanently. When the mask falls, something of value comes up. Masks are interesting partly for themselves and partly for what they mask. The reality behind the mask is like a shadow-creature rising to the bait: the tug of an unseen force, frightening and energetic. What emerges is a precious thing, precious because buried or lost or repressed.

Anyone who writes stories or novels or poems with some kind of narrative structure often imagines a central character, then gives that character a desire or a fear and perhaps some kind of goal and sets another character in a collision course with that person. The protagonist collides with an antagonist. All right: We know where we are. We often talk about this sort of dramatic conflict as if it were all unitary, all one of a kind: One person wants something, another person wants something else, and conflict results. But this is not, I think, the way most stories actually work. Not everything is a contest. We are not always fighting our brothers for our share of worldly goods. Many good stories have no antagonist at all.

Joan Didion

The most important is that I need an hour alone before dinner, with a drink, to go over what I've done that day. I can't do it late in the afternoon because I'm too close to it. Also, the drink helps. It removes me from the pages. So I spend this hour taking things out and putting other things in. Then I start the next day by redoing all of what I did the day before, following these evening notes. When I'm really working I don't like to go out or have anybody to dinner, because then I lose the hour. If I don't have the hour, and start the next day with just some bad pages and nowhere to go, I'm in low spirits. Another thing I need to do, when I'm near the end of the book, is sleep in the same room with it. That's one reason I go home to Sacramento to finish things. Somehow the book doesn't leave you when you're asleep right next to it. In Sacramento nobody cares if I appear or not. I can just get up and start typing.

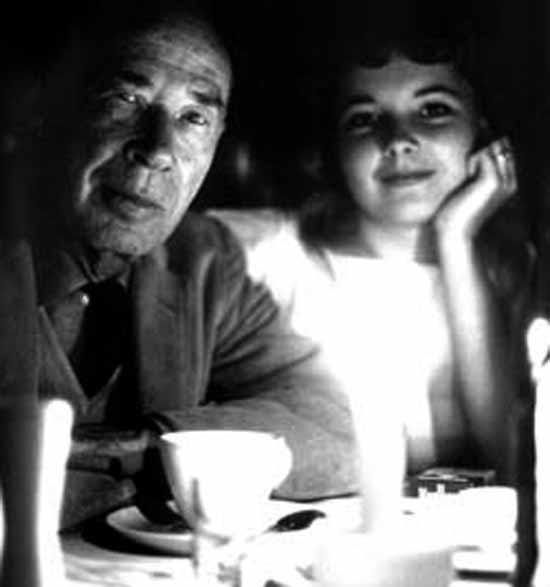

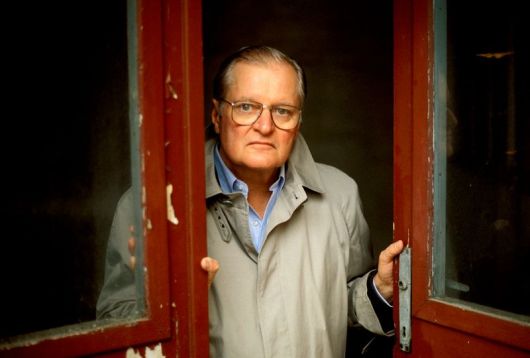

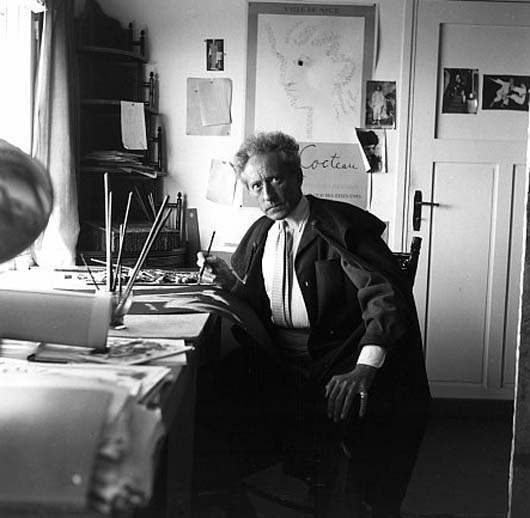

w.b. yeats (left) with andre gide (right)

w.b. yeats (left) with andre gide (right)

William Butler Yeats

In Paris Synge once said to me, "We should unite stoicism, asceticism and ecstasy. Two of them have often come together, but the three never."

I notice that in dreams our apparent subjective moods are almost limited to very elementary fear, grief, and desire. We are without complexity or any general consciousness of our state. If we are ill, our discomfort is transferred apparently from ourselves to the dream image. An image created by sexual desire, when our health is bad, may for instance be a woman with a swollen face, or some disagreeable behaviour. Indeed, when we are ill we often see deformed images. I suggest analogy between the form of the mind of the control, also superficial, and our apparent mind in dreams. The sense of identity is attenuated in both at the same points.

A good writer should be so simple that he has no faults, only sins.

Lyn Hejinian

Because we have language we find ourselves in a special and peculiar relationship to the objects, events and situations which constitute what we imagine of the world. Language generates its own characteristics in the human psychological and spiritual conditions. Indeed, it is near our psychological condition. This psychology is generated by the struggle between language and that which it claims to depict or express, by our overwhelming experience of the vastness and uncertainty of the world, and by what often seems to be the inadequacy of the imagination that longs to know it - and, furthermore, for the poet, the even greater inadequacy of the language that appears to describe, discuss, or disclose it. This psychology situates desire in the poem itself, or, more specifically, in poetic language, to which then we may attribute the motive for the poem.

Language is one of the principal forms our curiosity takes. It makes us restless. As Francis Ponge puts it, "Man is a curious body whose center of gravity is not in himself." Instead it seems to be located in language, by virtue of which we negotiate our mentalities and the world; off-balance, heavy at the mouth, we are pulled forward.

Jean Cocteau

I must make a disagreeable confession. I read nothing within the lines of my work. I find it very disconcerting; I disorient “the other.” I have not looked at a newspaper in twenty years; if one is brought into the room, I flee. This is not because I am indifferent but because one cannot follow every road. And nevertheless such a thing as the tragedy of Algeria undoubtedly enters into one's work, doubtless plays its role in the fatigued and useless state in which you find me. Not that "I do not wish to lose Algeria!" but the useless killing, killing for the sake of killing. In fear of the police, men keep to a certain conduct; but when they become the police they are terrible. No, one feels shame at being a part of the human race. About novels: I read detective fiction, espionage, science fiction.

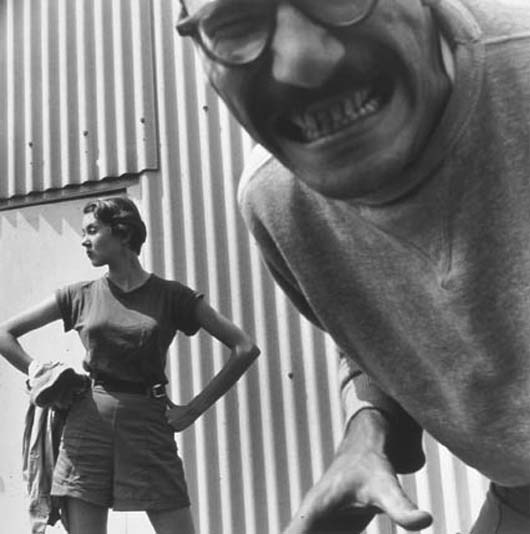

francine du plessix gray w/ jonathan williams at black mountain

francine du plessix gray w/ jonathan williams at black mountain

Francine du Plessix Gray

Recently the compulsion has been less intense, a week or two can go by and then I catch up in my big streak: angers and anxieties and sarcastic reports on overhead conversations, any snazzy metaphors that come to mind, phrases and ideas for current projects, a lot of nature notes — smells, sounds, colors, birds. I sometimes wonder why I have to look back and record precisely what I was experiencing on such and such a day. No one’s given a satisfactory explanation for this compulsion writers have to keep a laundry list of the soul: Virginia Woolf, her need to jot down who came to tea every day, and the pitch of Lytton Strachey’s voice and the kind of cucumber sandwiches she served. It’s as if we feel constantly other from the person we were the day, the hour before, and this sense of flux is terrifying, we have to crystallize, fix every moment of ourselves in order not to disappear altogether, as if our very identity were constantly threatened with dissolution.

I get up fairly early and have an overabundant physical energy in the early hours, even without caffeine, which I gave up decades ago. I’m rather like a hyperactive child in the morning, it’s very hard for me to sit still and concentrate on any writing then. So those hours are reserved for the more passive work: reading what I call my sacred texts, poetry or the Bible or the classics; recently I’ve gone through Lattimore’s translation of Homer, and Virgil’s Aeneid in the Fitzgerald translation, and a history of the cabala.

Then after this most treasured hour of the day, which I always spend alone upstairs in my room, with some tea and fruit and honey, I go about the business of life: notes to friends, shopping and planning for the family, answering phone calls, thanking people for this and that, thanking the world. As if I have to earn the right to write by being a good girl—all about me must be perfectly rinsed and dusted before I can start working. That’s in part due to my great fear of interruptions, but even more to an excessive proclivity to order and neatness that prevails in my mother’s family. Compulsive Slavic hospitality, and a tedious dutifulness and domesticity, are probably my most time-consuming vices.

Joyce Carol Oates

Stories come to us as wraiths requiring precise embodiments. Running seems to allow me, ideally, an expanded consciousness in which I can envision what I'm writing as a film or a dream. I rarely invent at the typewriter but recall what I've experienced. I don't use a word processor but write in longhand, at considerable length. (Again, I know: writers are crazy.)

By the time I come to type out my writing formally, I've envisioned it repeatedly. I've never thought of writing as the mere arrangement of words on the page but as the attempted embodiment of a vision: a complex of emotions, raw experience.

The effort of memorable art is to evoke in the reader or spectator emotions appropriate to that effort. Running is a meditation; more practicably it allows me to scroll through, in my mind's eye, the pages I've just written, proofreading for errors and improvements.

My method is one of continuous revision. While writing a long novel, every day I loop back to earlier sections to rewrite, in order to maintain a consistent, fluid voice. When I write the final two or three chapters of a novel, I write them simultaneously with the rewriting of the opening, so that, ideally at least, the novel is like a river uniformly flowing, each passage concurrent with all the others.

Gene Wolfe

Every so often I get optimistic and explain the best method of learning to write to students. I don't believe any of them has ever tried it, but I will explain it to you now. After all, you may be the exception. When I read about this method, it was attributed to Benjamin Franklin, who invented and discovered so much. Certainly I did not invent it.

But I did it, and it worked. That is more than can be said for most creative writing classes.

Find a very short story by a writer you admire. Read it over and over until you understand everything in it. Then read it over a lot more.

Here's the key part. You must do this. Put it away where you cannot get at it. You will have to find a way to do it that works for you. Mail the story to a friend and ask him to keep it for you, or whatever. I left the story I had studied in my desk on Friday. Having no weekend access to the building in which I worked, I could not get to it until Monday morning.

When you cannot see it again. Write it yourself. You know who the characters are. You know what happens. You write it. Make it as good as you can.

Compare your story to the original, when you have access to the original again. Is your version longer? Shorter? Why? Read both versions out loud. There will be places where you had trouble. Now you can see how the author handled those problems.

If you want to learn to write fiction, and are among those rare people willing to work at it, you might want to use the little story you have just finished as one of your models. It's about the right length.

Philip Levine

Thirty-five years ago I sat in small room with Robert Lowell, then my teacher, and asked him how I might lift from its doldrums a particular poem. Lowell had spent about fifteen minutes showing me why this poem was horseshit, something I already knew, for I had come to him not for praise but for help. He had just paused in his steady assault on my poem, when I asked him how I might go about making it better. We sat in silence for over a minute. Then he looked at me, a little resigned smile on his face, and said, "You know, it's damned hard to make sense and keep the rhythm."

Nothing was clearer to me than that Lowell was remembering his own experience, and yes, he was exactly right, it is damned hard to make sense, say something worth saying and not said a thousand times before, and keep the rhythm. That was my problem at the time, and of course it still is, and there would be other down the road, problems more difficult to locate and more impossible to deal with, and there would be no Lowell to go to for help.

Thomas Pynchon

I was more concerned with committing on paper a variety of abuses, such as overwriting. I will spare everybody a detailed discussion of all the overwriting that occurs in these stories, except to mention how distressed I am at the number of tendrils that keep showing up. I still don't even know for sure what a tendril is. I think I took the word from T.S. Eliot. I have nothing against tendrils personally, but my overuse of the word is a good example of what can happen when you spend too much time and energy on words alone.

This advice has been given often and more compellingly elsewhere, but my specific piece of wrong procedure back then was, incredibly, to browse through the thesaurus and note words that sounded cool, hip, or likely to produce an effect, usually that of making me look good, without then taking the trouble to go and find out in the dictionary what they meant. If this sounds stupid, it is. I mention it only on the chance that others may be doing it even as we speak, and be able to profit from my error.

This same free advice can also be applied to items of information. Everybody gets told to write about what they know. The trouble with many of us is that the earlier stages of life we are often unaware of the scope and structure of our ignorance. Ignorance is not just a blank space on a person's mental map. It has contours and coherence, and for all I know rules of operation as well. So as a corollary to writing about what we know, maybe we should add getting familiar with our ignorance, and the possibilities therein for ruining a good story.

Opera librettos, movies and television drama are allowed to get away with all kinds of errors in detail. Too much time in front of the Tube and a writer can get to believing the same thing about fiction. Not so. Though it may not be wrong absolutely to make up, as I still do, what I don't know or am too lazy to find out, phony data are more often than not deployed in places sensitive enough to make a difference, thereby losing what marginal charm they may have possessed outside of the story's context.

Witness an example from "Entropy." In the character of Callisto I was trying for a sort of world-weary Middle-European effect, and put in the phrase grippe espagnole, which I had seen on some liner notes to a recording of Stravinsky's L'Histoire du Soldat. I must have thought this was some kind of post-World War I spiritual malaise or something. Come to find out it means what it says, Spanish influenza, and the reference I lifted was really to the worldwide flu epidemic that followed the war.

Gertrude Stein

Every writer must have common sense. He must be sensitive and serious. But he must not grow solemn. He must not listen to himself. If he does, he might as well be under a tombstone. When he takes himself solemnly, he has no more to say. Yet he must despise nothing, not even solemn people. They are part of life and it’s his job to write about life.

Be direct. Indirectness ruins good writing. There is inner confusion in the world today and because of it people are turning back to old standards like children to their mothers. This makes indirect writing.

A writer must preserve a balance between sensitivity and vitality. Highbrow writers are sensitive but not vital. Commercial writers are vital but not sensitive. Trying to keep this balance is always hard. It is the whole job of living.

When one writes a thing — when you discover and then put it down, which is the essence of discovering it — one is done with it. What people get out of it is none of the writer’s business.

Every writer is self-conscious. It’s one reason he is a writer. And he is lonely. If you know three writers in a lifetime, that is a great many.

You do not have to write what the editors want. You can write what you want and if you develop sufficient craftsmanship, you can sell it, too. I want you to write for the Saturday Evening Post. It demands the best craftsmanship.

Roberto Bolaño

Now that I’m forty-four years old, I’m going to offer some advice on the art of writing short stories.

1. Never approach short stories one at a time. If one approaches short stories one at a time, one can quite honestly be writing the same short story until the day one dies.

2. It is best to write short stories three or five at a time. If one has the energy, write them nine or fifteen at a time.

3. Be careful: the temptation to write short stories two at a time is just as dangerous as attempting to write them one at a time, and, what’s more, it’s essentially like the interplay of lovers’ mirrors, creating a double image that produces melancholy.

4. One must read Horacio Quiroga, Felisberto Hernández, and Jorge Luis Borges. One must read Juan Rulfo and Augusto Monterroso. Any short-story writer who has some appreciation for these authors will never read Camilo José Cela or Francisco Umbral yet will, indeed, read Julio Cortázar and Adolfo Bioy Casares, but in no way Cela or Umbral.

5. I’ll repeat this once more in case it’s still not clear: don’t consider Cela or Umbral, whatsoever.

6. A short-story writer should be brave. It’s a sad fact to acknowledge, but that’s the way it is.

7. Short-story writers customarily brag about having read Petrus Borel. In fact, many short-story writers are notorious for trying to imitate Borel’s writing. What a huge mistake! Instead, they should imitate the way Borel dresses. But the truth is that they hardly know anything about him—or Théophile Gautier or Gérard de Nerval!

8. Let’s come to an agreement: read Petrus Borel, dress like Petrus Borel, but also read Jules Renard and Marcel Schwob. Above all, read Schwob, then move on to Alfonso Reyes and from there go to Borges.

9. The honest truth is that with Edgar Allan Poe, we would all have more than enough good material to read.

10. Give thought to point number 9. Think and reflect on it. You still have time. Think about number 9. To the extent possible, do so on bended knees.

11. One should also read a few other highly recommended books and authors— e.g., Peri hypsous, by the notable Pseudo-Longinus; the sonnets of the unfortunate and brave Philip Sidney, whose biography Lord Brooke wrote; The Spoon River Anthology, by Edgar Lee Masters; Suicidios ejemplares, by Enrique Vila-Matas; and Mientras ellas duermen by Javier Marías.

12. Read these books and also read Anton Chekhov and Raymond Carver, for one of the two of them is the best writer of the twentieth century.

translated from the Spanish by David Draper Clark

Eudora Welty

Ever since I was first read to, then started reading to myself, there has never been a line read that I didn't hear. As my eyes followed the sentence, a voice was saying it silently to me. It isn't my mother's voice, or the voice of any person I can identify, certainly not my own. It is human, but inward, and it is inwardly that I listen to it. It is to me the voice of the story or the poem itself. The cadence, whatever it is that asks you to believe, the feeling that resides in the printed word, reaches me through the reader-voice.

I have supposed, but never found out, that this is the case with all readers — to read as listeners. It may be part of the desire to write. The sound of what falls on the page begins the process of testing it for truth, for me. Whether I am right to trust so far I don't know. By now I don't know whether I could do either one, reading or writing, without the other. My own words, when I am at work on a story, I hear too as they go, in the same voice that I hear when I read in books. When I write and the sound of it comes back to my ears, then I act to make changes. I have always trusted this voice.

Don DeLillo

I think the scene comes first, an idea of a character in a place. It's visual, it's Technicolor — something I see in a vague way. Then sentence by sentence into the breach. No outlines — maybe a short list of items, chronological, that may represent the next twenty pages. But the basic work is built around the sentence. This is what I mean when I call myself a writer. I construct sentences. There's a rhythm I hear that drives me through a sentence. And the words typed on the white page have a sculptural quality. They form odd correspondences. They match up not just through meaning but through sound and look. The rhythm of a sentence will accommodate a certain number of syllables. One syllable too many, I look for another word. There's always another word that means nearly the same thing, and if it doesn't then I'll consider altering the meaning of a sentence to keep the rhythm, the syllable beat. I'm completely willing to let language press meaning upon me. Watching the way in which words match up, keeping the balance in a sentence — these are sensuous pleasures. I might want very and only in the same sentence, spaced in a particular way, exactly so far apart. I might want rapture matched with danger — I like to match word endings. I type rather than write longhand because I like the way words and letters look when they come off the hammers onto the page — finished, printed, beautifully formed.

When I was working on The Names I devised a new method — new to me, anyway. When I finished a paragraph, even a three-line paragraph, I automatically went to a fresh page to start the new paragraph. No crowded pages. This enabled me to see a given set of sentences more clearly. It made rewriting easier and more effective. The white space on the page helped me concentrate more deeply on what I'd written.

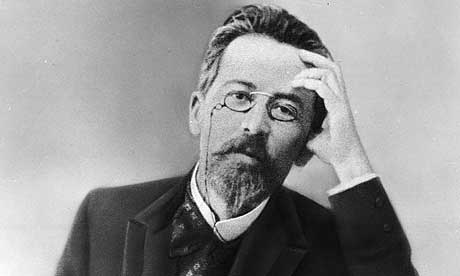

Anton Chekhov

One must be a god to be able to tell successes from failures without making a mistake.

I think descriptions of nature should be very short and always be à propos. Commonplaces like "The setting sun, sinking into the waves of the darkening sea, cast its purple gold rays, etc," "Swallows, flitting over the surface of the water, twittered gaily" — eliminate such commonplaces. You have to choose small details in describing nature, grouping them in such a way that if you close your eyes after reading it you can picture the whole thing. For example, you'll get a picture of a moonlit night if you write that on the dam of the mill a piece of broken bottle flashed like a bright star and the black shadow of a dog or a wolf rolled by like a ball, etc.

In the realm of psychology you also need details. God preserve you from commonplaces. Best of all, shun all descriptions of the characters' spiritual state. You must try to have that state emerge clearly from their actions. Don't try for too many characters. The center of gravity should reside in two: he and she.

When you describe the miserable and unfortunate, and want to make the reader feel pity, try to be somewhat colder — that seems to give a kind of background to another's grief, against which it stands out more clearly. Whereas in your story the characters cry and you sigh. Yes, be more cold. ... The more objective you are, the stronger will be the impression you make.

My own experience is that once a story has been written, one has to cross out the beginning and the end. It is there that we authors do most of our lying.

Mavis Gallant

I still do not know what impels anyone sound of mind to leave dry land and spend a lifetime describing people who do not exist. If it is child's play, an extension of make-believe - something one is frequently assured by persons who write about writing - how to account for the overriding wish to do just that, only that, and consider it as rational an occupation as riding a racing bike over the Alps? Perhaps the cultural attaché at a Canadian embassy who said to me "Yes, but what do you really do?" was expressing an adult opinion.

The impulse to write and the stubbornness needed to keep going are supposed to come out of some drastic shaking up, early in life. There is even a term for it: the shock of change. Probably, it means a jolt that unbolts the door between perception and imagination and leaves it ajar for life, or that fuses memory and language and waking dreams.

The first flash of fiction arrives without words. It consists of a fixed image, like a slide or (closer still) a freeze frame, showing characters in a simple situation.

Stories are not chapters of novels. They should not be read one after another, as if they were meant to follow along. Read one. Shut the book. Read something else. Come back later. Stories can wait.

Stanley Elkin

My editor at Random House, Joe Fox, used to tell me, “Stanley, less is more.” He wanted to strike — oh, he had a marvelous eye for the “good” stuff — and that’s what he wanted to strike. I had to fight him tooth and nail in the better restaurants to maintain excess because I don’t believe that less is more. I believe that more is more. I believe that less is less, fat fat, thin thin and enough is enough. There’s a famous exchange between Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe in which Fitzgerald criticizes Wolfe for one of his novels. Fitzgerald tells him that Flaubert believed in the mot précis and that there are two kinds of writers—the putter-inners and the taker-outers. Wolfe, who probably was not as good a writer as Fitzgerald but evidently wrote a better letter, said, “Flaubert me no Flauberts. Shakespeare was a putter-inner, Melville was a putter-inner.”* I can’t remember who else was a putter-inner, but I’d rather be a putter-inner than a taker-outer.

I do have an ideal audience in mind. That ideal audience is a man like Bill Gass, or someone like Howard Nemerov, or any other writer who respects language. But other than that, no notion at all of an audience. I don’t think any writer does. I don’t think that poor Jacqueline Susann had any notion of an audience. I think she was doing the best she could. There is no such thing as prostitution in writing. One writes what one can write. One writes up, though one man’s up is another man’s basement.

Like most people of my generation, I fell in love with the philosophy of existentialism. There is no particular religious tradition in my work. There is only one psychological assertion that I would insist upon. That is: the self takes precedence.

"Ladytron" - Venus in Furs (mp3)

"Baby's On Fire" - Venus in Furs (mp3)

"2HB" - Venus in Furs (mp3)