TV

TV In Which We Have Killed Before Long Ago

Friday, October 6, 2017 at 12:17PM

Friday, October 6, 2017 at 12:17PM

Canadian Noose

by ELEANOR MORROW

Alias Grace

creators Sarah Polley and Mary Harron

CBC/Netflix

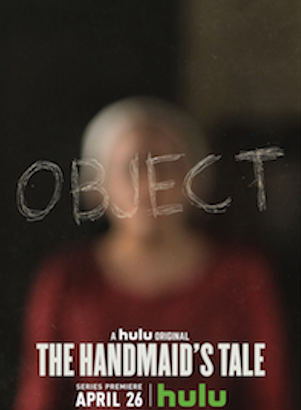

I have searched, sometimes in vain, sometimes pleasurably, for what Sarah Polley likes about Margaret Atwood’s novel about the 1843 murders of two Canadians. Alias Grace, a miniseries in six parts, opens with the languorous voiceover of Grace Marks (Sarah Gadon), who explains with a monologue virtually identical to that found in The Handmaid’s Tale, about why she is a rotten woman. At first you do not believe her verbal tale of self-immolation, but then the sheer amount of time she spends denigrating herself wins out. She is a bad gal, so what does that make everyone else in her world?

I have searched, sometimes in vain, sometimes pleasurably, for what Sarah Polley likes about Margaret Atwood’s novel about the 1843 murders of two Canadians. Alias Grace, a miniseries in six parts, opens with the languorous voiceover of Grace Marks (Sarah Gadon), who explains with a monologue virtually identical to that found in The Handmaid’s Tale, about why she is a rotten woman. At first you do not believe her verbal tale of self-immolation, but then the sheer amount of time she spends denigrating herself wins out. She is a bad gal, so what does that make everyone else in her world?

A local reverend (David Cronenberg) wants Grace freed from her lengthy stay in prison as a result of a murder conviction, so he invokes the presence of an alienist named Dr. Jordan (Edward Holcroft). His plan of treatment initially frightens Grace, since she has grown used to various quacks scanning her brain with primitive metal rods. Alias Grace never becomes very exciting. It is mostly just sad, but halfway through you surmise that it is intended to be like this.

In this central role, Gadon has her ups and downs. Overall, her performance is understated and at times rather sleepily. Mary Harron (American Psycho) always directs her actors in this fashion, and it would probably work in this period context if almost every other character did not project the same sleepy egoism.

The exception to the rule is Mary (the stunning Canadian actress Rebecca Liddiard), a servant at a bourgeois Canadian manor where Grace finds work. Her entrance about halfway through the miniseries’ first installment is a shotgun blast of energy to this dreary milieu.

Not helping matters is the frame story, which places all of Alias Grace in flashback. Similar to how The Handmaid’s Tale at times felt held back by its extensive exposition, Alias Grace struggles to decide whether its present or past is more vital. Ironically, this is the very test that every historical depiction must surmount. Instead of making us feel like this 19th century tale has something fresh to say about the present, (and at times it does), I was fixated on how everyone here seems absolutely miserable in the past.

Visually, Alias Grace is an absolute feast for the eyes. Harron's eye for how the right set conveys the meaning of a particular scene is surpassed in her industry only by Jane Campion and Guillermo Del Toro, and she dives into as much compositional depth as Del Toro does at his height.

Within Atwood’s massive oeuvre, Alias Grace never approaches the wild highs of her best fantasies. To be fair, it is not meant to. Still, I feel her more rambunctious, silly work tends to match our current period better. I wish Polley would work on Oryx & Crake, her undisputed masterpiece, or some of her more recent sex satires. Polley is such a strong writer that you stick with Alias Grace long after the characters seem to solidify into granite.

Eleanor Morrow is the senior contributor to This Recording.