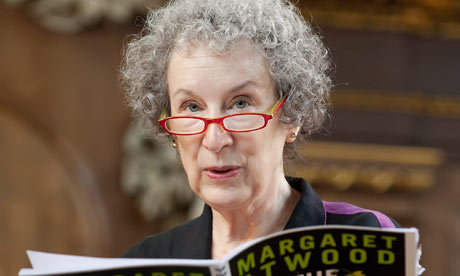

On Being A 'Woman Writer'

by MARGARET ATWOOD

I approach this article with a good deal of reluctance. Once having promised to do it, in fact, I've been procrastinating to such an extent that my own aversion is probably the first subject I should attempt to deal with. Some of my reservations have to do with the questionable value of writers, male or female, becoming directly involved in political movements of any sort: their involvement may be good for the movement, but it's yet to be demonstrated that it's good for the writer.

The rest concern my sense of the enormous complexity not only of the relationships between Man and Woman, but also of those between other abstract intangibles, Art and Life, Form and Content, Writer and Critic, et cetera.

Judging from conversations I've had with many other women writers in this country, my qualms are not unique. I can think of only one writer I know who has any formal connection with any of the diverse organizations usually lumped together under the titles of Women's Liberation or the Women's Movement. There are several who have gone out of their way to disavow even any fellow-feeling, but the usual attitude is one of grudging admiration, tempered with envy: the younger generation, they feel, has it a hell of a lot better than they did. Most writers old enough to have a career of any length behind them grew up when it was still assumed that a woman's place was in the home and nowhere else, and that anyone who took time off for an individual selfish activity like writing was either neurotic or wicked or both, derelict in her duties to a man, child, aged relatives or whoever else was supposed to justify her existence on earth.

I've heard stories of writers so consumed by guilt over what they had been taught to feel was their abnormality that they did their writing at night, secretly, so that no one would accuse them of failing as housewives, as "women."

These writers accomplished what they did by themselves, often at great personal expense; in order to write at all, they had to defy other women's as well as men's ideas of what was proper, and it's not finally all that comforting to have a phalanx of women — some younger and relatively unscathed, others from their generation, the bunch that was collecting china, changing diapers, and sneering at any female with intellectual pretensions twenty or even ten years ago — come breezing up now to tell them they were right all along. It's like being judged innocent after you've been hanged: the satisfaction, if any, is grim.

There's a great temptation to say to Womens' Lib, "Where were you when I really needed you?" or "It's too late for me now." And you can see, too, that it would be fairly galling for these writers, if they have any respect for historical accuracy, which most do, to be hailed as products, spokeswomen, or advocates of the Women's Movement. When they were undergoing their often drastic formative years there was no Women's Movement.

No matter that a lot of what they say can be taken by the theorists of the Movement as supporting evidence, useful analysis, and so forth: their own inspiration was not theoretical, it came from wherever all writing comes from. Call it experience and imagination. These writers, if they are honest, don't want to be wrongly identified as the children of a movement that did not give birth to them. Being adopted is not the same as being born.

A third area of reservation is undoubtedly a fear of the development of a one-dimensional Feminist Criticism, a way of approaching literature producing by women that would award points according to conformity or non-conformity to an ideological position.

A feminist criticism is, in fact, already emerging. I've read at least one review, and I'm sure there have been and will be more, in which the novelist was criticized for not having made her heroine's life different, even though that life was more typical of the average women's life in society than the reviewer's "liberated" version would have been.

Perhaps Women's Lib reviewers will start demanding that heroines resolve their difficulties with husband, kids, or themselves by stomping out to join a consciousness raising group, which will be no more satisfactory from the point of view of literature than the legendary Socialist Realist romance with one's tractor.

However, a feminist criticism need not necessarily be one-dimensional. And — small comfort — no matter how narrow, purblind and stupid such a criticism in its lowest manifestations may be, it cannot possible be more narrow, purblind and stupid than some of the non-feminist critical attitudes that have preceded it.

There's a fourth possible factor, a less noble one: the often observed phenomenon of the member of a despised social group who managers to transcend the limitations imposed on the group, at least enough to become "successful." For such a person the impulse — whether obeyed or not — is to disassociate him/herself from the group and side with its implicit opponents. Thus the Black millionaire who deplores the Panthers, the rich Quebecois who is anti-Separatist, the North American immigrant who changes his name to an "English" one; thus, alas the Canadian writer who makes it, sort of, in New York, and spends many magazine pages decrying the provincial dull Canadian writers; and thus the women with successful careers who say, "I've never had any problems, I don't know what they're talking about."

Such a woman tends to regard herself, and to be treated by her male colleagues, as a sort of honorary man. It's the rest of them who are inept, brainless, tearful, self-defeating: not her. "You think like a man," she is told, with admiration and unconscious put down. For both men and women, it's just too much of a strain to fit together the traditionally incompatible notions of "woman" and "good at something."

And if you are good at something, why carry with you the stigma attached to the dismal category you've gone to such lengths to escape from? The only reason for rocking the boat is if you're still chained to the oars. Not everyone reacts like this, but this factor may explain some of the more hysterical opposition to Women's Lib on the part of the few woman writers, even though they may have benefitted from the Movement in the form of increased sales and more serious attention.

with her father in Northern Quebec in 1942

A couple of ironies remain; perhaps they are even paradoxes. One is that, in the development of modern Western civilization, writing was the first of the arts, before painting, music, composing, and sculpting, which it was possible for women to practice; and it was the fourth of the job categories, after prostitution, domestic service and the stage, and before wide-scale factory work, nursing, secretarial work, telephone operation and school teaching, at which it was possible for them to make any money.

The reason for both is the same: writing as a physical activity is private.

You do it by yourself, or on your own time; no teachers or employers are no involved, you don't have to apprentice in a studio or work with musicians. Your only business arrangements are with your publisher, and these can be conducted through the mails; your real "employers" can be deceived, if you choose, by the adoption of the assumed (male) name; witness the Brontes and George Eliot. But the private and individual nature of writing may also account for the low incidence of direct involvement by woman writers in the Movement now.

If you are a writer, prejudice against women will affect you as a writer not directly but indirectly. You won't suffer from wage discrimination, because you aren't paid any wages; you won't be hired last and fired first, because you aren't hired or fired anyway. You have relatively little to complain of, and, absorbed in your own work as you are likely to be, you will find it quite easy to shut your eyes to what goes on at the spool factory, or even at the university. Paradox: reason for involvement then equals reason for non-involvement now.

Another paradox goes like this. As writers, woman writers are like other writers. They have the same professional concerns, they have to deal with the same contracts and publishing procedures, they have the same need for solitude to work and the same concern that their work be accurately evaluated by reviewers. There is nothing "male" or "female" about these conditions: they are just attributes of the activity known as writing. As biological specimens and as citizens, however, women are like other women: subject to the same discriminatory laws, encountering the same demeaning attitudes, burdened with the same good reasons for not walking through the park alone after dark. They too have bodies, the capacity to bear children; they eat, sleep and bleed, just like everyone else.

In bookstores and publishers' offices and among groups of other writers, a woman writer may get the impression that she is "special;" but in the eyes of the law, in the loan office or bank, in the hospital and on the street she's just another woman. She doesn't get to wear a sign to the grocery store saying "Respect me, I'm a Woman Writer." No matter how good she may feel about herself, strangers who aren't aware of her shelf-full of nifty volumes with cover blurbs saying how gifted she is will still regard her as a nit.

We all have ways of filtering out aspects of our experience we would rather not think about. Woman writers can keep as much as possible to the "writing" end of their life, avoiding the less desirable aspects of the "woman" end. Or they can divide themselves in two, thinking of themselves as two different people: a "writer" and a "woman." Time after time, I've had interviewers talk to me about my writing for a while, then ask me, "As a woman, what do you think about — for instance — the Women's Movement?" as if I could think two sets of thoughts about the same thing, one set as a writer or person, the other as a woman. But no one comes apart this easily; categories like Woman, White, Canadian, Writer only ways of looking at a thing, and the thing itself is whole, entire and indivisible. Paradox: Woman and Writer are separate categories; but in any individual woman writer, they are inseparable.

Margaret and siblings in a log cabin in Quebec, 1952

One of the results of the paradox is that there are certain attitudes, some overt, some concealed, which women writers encounter as writers, but because they are women. I shall try to deal with a few of these, as objectively as I can.

Reviewing and the Absence of An Adequate Critical Vocabulary

Cynthia Ozick, in the American magazine Ms., says, "For many years, I had noticed that no book of poetry was ever reviewed without reference to the poet's sex. The curious thing was that, in the two decades of my scrutiny, there were no exceptions whatever. It did not matter whether the reviewer was a man or a woman, in every case, the question of a 'feminine sensibility' of the poet was at the center of the reviewer's response. The maleness of male poets, on the other hand, hardly ever seemed to matter."

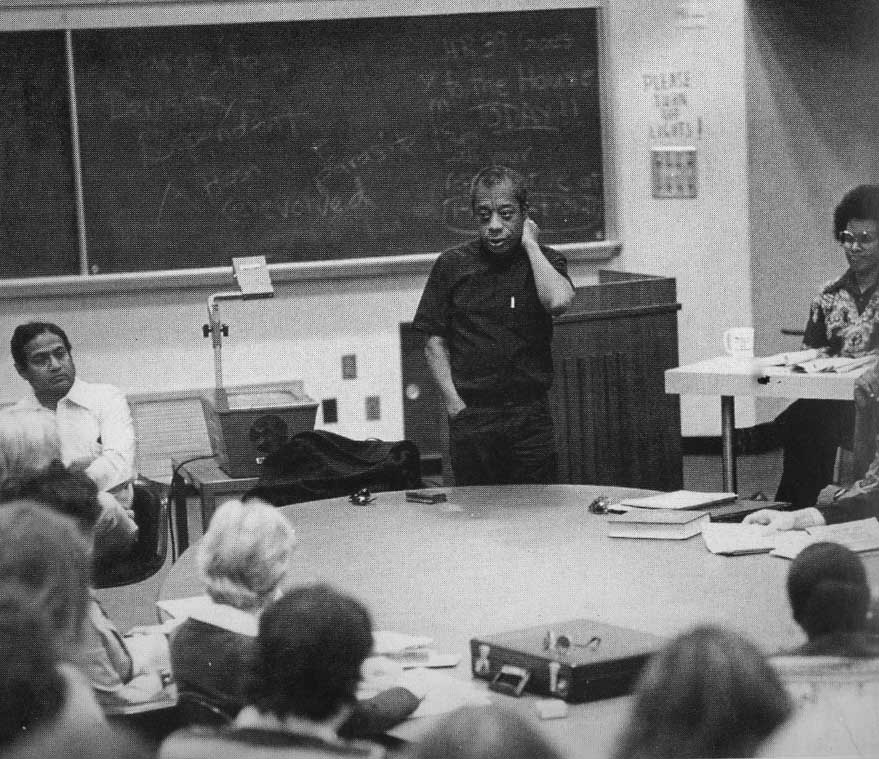

Things aren't this bad in Canada, possibly because we were never fully indoctrinated with the Holy Gospel according to the distorters of Freud. Many reviewers manage to get through a review without displaying the kind of bias Ozick is talking about. But that it does occur was demonstrated to me by a project I was involved with at York University in 1971-72.

One of my groups was attempting to study what we called "sexual bias in reviewing," by which we meant not unfavorable reviews, but points being added or subtracted by the reviewer on the basis of the author's sex and supposedly associated characteristics rather than on the basis of the work itself. Our study fell into two parts: i) a survey of writers, half male, half female, conducted by letter: had they ever experienced sexual bias directed against them in a review? ii) the reading of the larger number of reviews from a wide range of periodicals and newspapers.

Niagara Falls, 1953

The results of the writers' survey were perhaps predictable. Of the men, none said Yes, a quarter said Maybe, and three quarters said No. Half of the women said Yes, a quarter said Maybe and a quarter said No. The women replying Yes often wrote long, detailed letters, giving instances and discussing their own attitudes. All the men's letters were short.

This proved only that women were more likely to feel they had been discriminated against on the basis of sex. When we got around to the reviews, we discovered that they were sometimes justified. Here are the kinds of things we found.

Assignment of reviews

Several of our letter writers mentioned this. Some felt books by women tended to be passed over by book-page editors assigning books for review; others that books by women tended to get assigned to women reviewers. When we started totting up reviews we found that most books in this society are written by men, and so are most reviews. Disproportionately often, books by women were assigned to women reviewers, indicating that books by women fell in the minds of those dishing out the reviews into some kind of "special" category. Likewise, woman reviewers tended to be reviewing books by women rather than by men (though because of the preponderance of male reviewers, there were quite a few male-written reviews of books by women).

The Quiller-Couch Syndrome

The heading of this one refers to the turn-of-the-century essay by Quiller-Couch, defining "masculine" and "feminine" styles in writing. The "masculine" style is, of course, bold, forceful, clear, vigorous, etc; the "feminine" style is vague, weak, tremulous, pastel, etc. In the list of pairs you can include, "objective" and "subjective," 'universal" or "accurate depiction of society" versus "confessional," "personal," or even "narcissistic" and "neurotic." It's roughly seventy years since Quiller-Couch's essay, but the "masculine" group of adjectives is still much more likely to be applied to the work of male writers; female writers are much more likely to get hit with some version of "the feminine style" or "feminine sensibility," whether their work merits it or not.

The Lady Painter, or She Writes Like A Man

This is a pattern in which good equals male, and bad equals female. I call it the Lady Painter Syndrome because of a conversation I had about female painters with a male painter in 1960. "When she's good," he said, "we call her a painter; when she's bad, we call her a lady painter." "She writes like a man" is part of the same pattern; it's usually used by a male reviewer who is impressed by a female writer. It's meant as a compliment. See also "She thinks like a man," which means the author thinks, unlike most women, who are held to be incapable of objective thought (their province is "feeling"). Adjectives which often have similar connotations are ones such as "strong," "gutsy," "hard," "mean," etc. A hard-hitting piece of writing by a man is liable to be thought of as merely realistic; an equivalent piece by a woman is much more likely to be labelled "cruel" or "tough." The assumption is that women are by nature soft, weak, and not very good, and that if a woman writer happens to be good, she should be deprived of her identity and provided with a higher (male) status.

In Cambridge, 1963

Thus the woman writer has, in the minds of such reviewers, two choices. She can be bad but female, a carrier of the "feminine sensibility" virus; or she can be "good" in male-adjective terms, but sexless. Badness seems to be ascribed then to a surplus of female hormones, whereas badness in a male writer is usually ascribed to nothing but badness (though a "bad" male writer is sometimes held, by adjectives implying sterility or impotence, to be deficient in maleness).

"Maleness" is exemplified by the "good" male writer; "femaleness," since it is seen by such reviewers as a handicap or deficiency, is held to be transcended or discarded by the "good" female one. In other words, there is no critical vocabulary for expressing the concept "good/female." Work by a male writer is often spoken of by critics admiring it as having "balls;" ever hear anyone speak admiringly of work by a woman as having "tits"?

Possible antidotes: Development of a "good/female" vocabulary ("Wow, has that ever got Womb..."); or preferably the development of a vocabulary that can treat structures made of words as though they are exactly that, not biological entities possessed of sexual organs.

Domesticity

One of our writers noted a (usually male) habit of concentrating on domestic themes in the work of a female writer, ignoring any other topic she might have dealt with, then patronizing her for an excessive interest in domestic themes. We found several instances of reviewers identifying an author as a "housewife" and consequently dismissing anything she has produced (since, in our society, a "housewife" is viewed as a relatively brainless and talentless creature). We even found one instance in which the author was called a "housewife" and put down for writing like one when in fact she was no such thing.

For such reviewers, when a man writes about things like doing the dishes, it's realism, when a woman does, it's an unfortunate feminine genetic limitation.

Sexual compliment put-down

This syndrome can be summed up as follows:

She: How do you like my (design for an airplane/mathematical formula/medical miracle)?

He: You sure have a nice ass.

In reviewing it usually takes the form of commenting on a cute picture of the (female) author on the cover, coupled with dismissal of her as a writer.

Panic Reaction

When something the author writes hits too close to home, panic reaction may set in. One of our correspondents noticed this phenomenon in connection with one of her books: she felt the content of the book threatened male reviewers, who gave it much worse reviews than did any female reviewer. Their reaction seemed to be that if a character such as she'd depicted did exist, they didn't want to know about it. In panic reaction, a reviewer is reacting to content, not to technique or craftsmanship or a book's internal coherence or faithfulness to its own assumptions.

(Panic reaction can be touched off in any area, not just male-female relationships.)

Interviewers and Media Stereotypes

Associated with the reviewing problem, but distinct from it, is the problem of the interview. Reviewers are supposed to concentrate on books, interviewers on the writer as a person, human being, or, in the case of women, woman. This means that an interviewer is ostensibly trying to find out what sort of person you are. In reality, he or she may merely be trying to match you up with a stereotype of "Woman Author" that pre-exits in her/his mind; doing it that way is both easier for the interviewer, since it limits the range and slant of questions, and shorter, since the interview can be practically written in advance. It isn't just women who get this treatment: all writers get it. But the range for male authors is somewhat wider and usually comes from the literary tradition itself, whereas stereotypes for female authors are often borrowed from other media, since the ones provided by the tradition are limited in number.

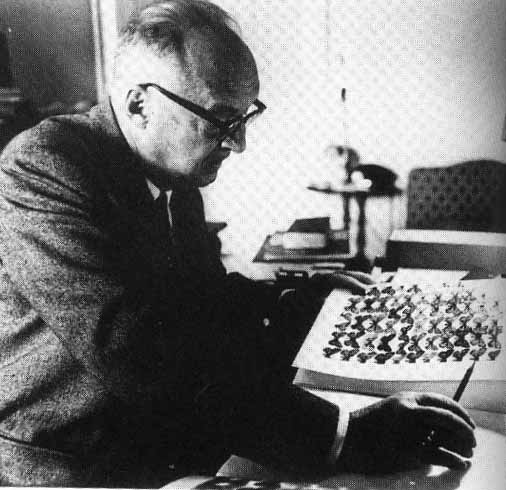

writing The Handmaid's Tale in Berlin, 1984

In a bourgeois, industrial society, so the theory goes, the creative artist is supposed to act out suppressed desires and prohibited activities for the audience; thus we get certain Post-romantic male-author stereotypes, such as Potted Poe, Bleeding Byron, Doomed Dylan, Lustful Layton, Crucified Cohen, etc. Until recently the only personality stereotype of this kind was Elusive Emily, otherwise known as Recluse Rossetti: the woman writer as aberration, neurotically denying herself the delights of sex, kiddies and other fun.

The Twentieth Century has added Suicidal Sylvia, a somewhat more dire version of the same thing. The point about these stereotypes is that attention is focused not on the actual achievements of the authors, but on their lives, which are distorted and romanticized; their work is then interpreted in the light of the distorted version. Stereotypes like these, even when the author cooperates in their formation and especially when the author becomes a cult object, do no service to anyone or anything, least of all the author's work.

Behind all of them is the notion that authors must be more special, peculiar or weird than other people, and that their lives are more interesting than their work.

The following examples are taken from personal experience (mine, of interviewers); they indicate the range of possibilities. There are a few others, such as Earth Mother, but for those you have to be older.

with Dolly Parton at the Ms. Magazine Awards

Happy Housewife

This one is almost obsolete: it used to be for Woman's Page or programme. Questions were about what you liked to fix for dinner; attitude was, "Gosh, all the housework and you're a writer, too!" Writing was viewed as a hobby, like knitting, one did in one's spare time.

Ophelia

The writer as crazy freak. Female version of Doomed Dylan, with more than a little hope on the part of the interviewer that you'll turn into Suicidal Sylvia and give them something to really write about. Questions like "Do you think you're in danger of going insane?" or "Are writers closer to insanity than other people?" No need to point out that most mental institutions are crammed with people who have never written a word in their life. "Say something interesting," one interviewer said to me. "Say you write all your poems on drugs."

Miss Marty; or Movie Mag

Read any movie mag on Liz Taylor and translate into writing terms and you've got the picture. The writer as someone who suffers more than others. Why does the writer suffer more? Because she's successful, and you all know Success Must Be Paid For. In blood and tears, if possible. If you say you're happy and enjoy your life and work, you'll be ignored.

with her agent

Miss Message

Interviewer incapable of treating your work as what it is, i.e. poetry and/or fiction. Great attempt to get you to say something about an Issue and then make you into an exponent, spokeswoman or theorist. (The two Messages I'm most frequently saddled with are Women's Lib and Canadian nationalism, though I belong to no formal organization devoted to either.) Interviewer unable to see that putting, for instance, a nationalist in a novel doesn't make it a nationalistic novel, any more than putting in a preacher makes it a religious novel. Interviewer incapable of handling more than one dimension at a time.

What Is Hard to Find is an interviewer who regards writing as a respectable profession, not as some kind of magic, madness, trickery, or evasive disguise for a Message; and who regards an author as someone engaged in a professional activity.

Other Writers and Rivalry

Regarding yourself as an "exception," part of an unspoken quota system, can have interesting results. If there are only so many available slots for your minority in the medical school/law school/literary world, of course you will feel rivalry, not only with members of the majority for whom no quota operates, but especially for members of your minority who are competing with you for the few coveted places. And you will have to be better than the average Majority member to get in at all. But we're familiar with that.

Woman-woman rivalry does occur, though it is surprisingly less severe than you'd expect; it's likely to take the form of wanting another woman writer to be better than she is, expecting more of her than you would of a male writer, and being exasperated with certain kinds of traditional "female" writing.

One of our correspondents discussed these biases and expectations very thoroughly and with great intelligence: her letter didn't solve any problems, but it did emphasize the complexities of the situation. Male-male rivalry is more extreme; we've all been treated to media-exploited examples of it.

What a woman writer is often unprepared for is the unexpected personal attack on her by a jealous male writer. The motivation is envy and competitiveness, but the form is often sexual put-down. "You may be a good writer," one older man said to a young woman writer who had just had a publishing success, "but I wouldn't want to fuck you." Another version goes more like the compliment put-down. in either case, the ploy diverts attention from the woman's achievement as a writer — the area where the man feels threatened — to her sexuality, where either way he can score a verbal point.

Personal Statement

I've been trying to give you a picture of the arena, or that part of it where being a "woman" and "writer," as concepts, overlap. But, of course, the arena I've been talking about has to do largely with externals: reviewing, the media, relationships with other writers. This, for the writer, may affect the tangibles of her career: how she is received, how viewed, how much money she makes. But in relationship to the writing itself, this is a false arena. The real one is in her head, her real struggle, the daily battle with words, the language itself. The false arena becomes valid for writing itself only insofar as it becomes part of her material and is transformed into one of the verbal and imaginative structures she is constantly engaged in making. Writers, as writers, are not propagandists or examples of social trends or preachers or politicians. They are makers of books, and unless they can make books well they will be bad writers, no matter what the social validity of their views.

At the beginning of this article, I suggested a few reasons for the infrequent participation in the Movement of woman writers. Maybe these reasons were the wrong ones, and this is the real one: no good writer wants to be merely a transmitter of someone's ideology, no matter how fine that ideology may be. The aim of propaganda is to convince, and to spur people to action; the aim of writing is to create a plausible and moving imaginative world, and to create it from words. Or, to put it another way, the aim of political movement is to improve the quality of people's lives on all levels, spiritual and imaginative as well as material (and any political movement that doesn't have this aim is worth nothing).

Writing, however, tends to concentrate more on life, not as it ought to be, but as it is, as the writer feels it, experiences it. Writers are eye-witnesses, I-witnesses. political movements, once successful, have historically been intolerant of writers, even those writers who initially aided them; in any revolution, writers have been among the first to be lined up against the wall, perhaps for their intransigence, their insistence on saying what they perceive, not what, according to the ideology, ought to exist.

Politicians, even revolutionary politicians, have traditionally had no more respect for writing as an activity valuable in itself, quite apart from any message or content, than has the rest of society. And writers, even revolutionaries writers, have traditionally been suspicious of anyone who tells them what they ought to write.

Politicians, even revolutionary politicians, have traditionally had no more respect for writing as an activity valuable in itself, quite apart from any message or content, than has the rest of society. And writers, even revolutionaries writers, have traditionally been suspicious of anyone who tells them what they ought to write.

The woman writer, then, exists in a society that, though it may turn certain individual writers into revered cult objects, has little respect for writing as a profession, and not much respect for women either. If there were more of both, articles like this would be obsolete. I hope they become so. In the meantime, it seems to me that the proper path for a woman writer is not an all-out manning (or womaning) of the barricades, however much she may agree with the aims of the Movement.

The proper path is become better as a writer. Insofar as writers are lenses, condensers of their society, her work may include the Movement, since it is so palpably among the things that exist. The picture that she gives of it is altogether another thing, and will depend, at least partly, on the course of the Movement itself.

Margaret Atwood is one of Canada's finest writers and critics.This essay appeared in Women in the Canadian Mosaic in 1976, and you can buy Atwood's collection Second Words here.

"Kandi" - One Eskimo (mp3)

"Balloons" - One Eskimo (mp3)

"Amazing" - One Eskimo (mp3)

BOOKS

BOOKS  Monday, October 21, 2013 at 11:19AM

Monday, October 21, 2013 at 11:19AM  illustration by jason courtney

illustration by jason courtney I once knew a writer who created, in a series of novels, a charismatic detective. Over time he began to loathe his own sleuth, and dreamed of killing him. Something like that happened with Margaret Atwood in the ensuing years since her brash novel of the future, Oryx & Crake, induced a subgenre of speculative fiction. 2009's The Year of the Flood followed, and the trilogy is concluded with MaddAddam, out from Bloomsbury this year.

I once knew a writer who created, in a series of novels, a charismatic detective. Over time he began to loathe his own sleuth, and dreamed of killing him. Something like that happened with Margaret Atwood in the ensuing years since her brash novel of the future, Oryx & Crake, induced a subgenre of speculative fiction. 2009's The Year of the Flood followed, and the trilogy is concluded with MaddAddam, out from Bloomsbury this year.

illustration by jason courtney

illustration by jason courtney