BOOKS

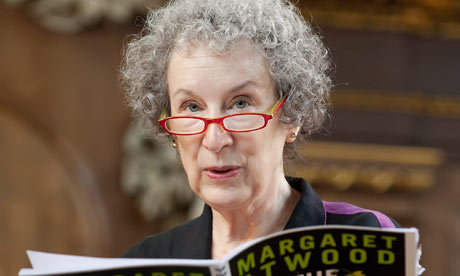

BOOKS In Which Margaret Atwood So Impotently Loved The World

Monday, October 21, 2013 at 11:19AM

Monday, October 21, 2013 at 11:19AM  illustration by jason courtney

illustration by jason courtney

Old Fashioned

by ALEX CARNEVALE

MaddAddam

by Margaret Atwood

331 pp

I once knew a writer who created, in a series of novels, a charismatic detective. Over time he began to loathe his own sleuth, and dreamed of killing him. Something like that happened with Margaret Atwood in the ensuing years since her brash novel of the future, Oryx & Crake, induced a subgenre of speculative fiction. 2009's The Year of the Flood followed, and the trilogy is concluded with MaddAddam, out from Bloomsbury this year.

I once knew a writer who created, in a series of novels, a charismatic detective. Over time he began to loathe his own sleuth, and dreamed of killing him. Something like that happened with Margaret Atwood in the ensuing years since her brash novel of the future, Oryx & Crake, induced a subgenre of speculative fiction. 2009's The Year of the Flood followed, and the trilogy is concluded with MaddAddam, out from Bloomsbury this year.

The inviolable, elusive Crake was her detective. There is still so much we do not know about Crake. What is certain is that he had parents, but that they died. His father was murdered by the government, and his mother took up with another man who Crake called his uncle. After this/because of this, at some indeterminate point, Crake decided to change humanity permanently. To inculcate his plan, he started playing a computer game online with some friends.

The singular invention of Atwood's novels is the existence of the Crakers, the homo sapiens spin-off that Crake made with his online friends in order to ensure Earth would be a better place for everyone to live. They are small, gendered creatures of mirth and happiness who speak to animals and feel no shame of their sex. Their genitals, penis and vagina both, glow blue in excitement.

In 2003, Usenet groups and stuff were recent history. Atwood updated the cultural references for the satire in MaddAddam, since the original corporate puns (Helthwyzer, AnooYoo) that constituted her ridicule were dated at the time she wrote them. The important thing is that we do and do not recognize our world in this bleak parody of it.

Usenet is old-fashioned like Crake, who played an online game called Extinctathon instead of a more fashionable tract. Atwood rewrote the story of Crake from the perspective of all the women in the novel in the next two volumes, shedding light on Crake in small mysterious scenes told by those knew him before. He was sort of a creep, really, but we cannot say that for certain, since there is still so much about those who made us that we do not really know.

The central figure of MaddAddam is a woman named Toby who knew Crake. The main thing about her that engenders our sympathy is her love for a man in their group, Zeb, and her rage at the possibility of his betrayal.

Toby's relationship with a Craker named Blackbeard is actually the central one. He appears to be her bedmate at times. (Humans and Crakers produce small, green-eyed offspring with blue genitals.) Blackbeard is a young Craker, the first Craker to learn how to write in the short history of the Crakers. He writes:

And in the book she put the Words of Crake, and the Words of Oryx as well, and of how together they made us, and made also this safe and beautiful World for us to live in...

And Toby set down also the Words about Amanda and Ren and Swift Fox, our Beloved Three Oryx Mothers, who showed us that we and the two-skinned ones are all people and helpers, though we have different gifts, and some of us turn blue and some do not.

So Toby said we must be respectful, and always ask first, to see if a woman is really blue or is just smelling blue, when there is a question about blue things.

And Toby showed me what to do when there should be no more pens of plastic, and no more pencils either; for she could look into the future, and see that a time would come when no pens or pencils or paper could be found any more, among the buildings of the city of chaos, where they used to grow.

And she showed me how to use the quill feathers of birds to make the pens, though we also made some pens from the ribs of a broken umbrella.

An umbrella is a thing from the chaos. They used it for keeping the rain off their bodies.

I don’t know why they did that.

This language is childlike, but it is not childish. It is the most fun to watch Atwood communicate in these ways, when it feels like she is rewriting language itself in order to speak more honestly. As Chesterton wrote, "Satire may be mad and anarchic, but it presupposes an admitted superiority in certain things over others." MaddAddam mostly abandons the hit or miss satire of Oryx & Crake, replacing it with descriptions of Atwood's improvements to Earth.

In MaddAddam, Atwood discovers a new standard, a better way of living. Here all the detritus that filled the streets and avenues — branding, high level MMO play, government spying — has been cleared out. Things really are better because of Crake, we come to understand, and that is a more bracing critique than a pun or the recording of a cliche.

Atwood's perspective demands so much of the world. She holds mankind to the same standard she holds individual people, which is a rather high one. Like all liberals she is not as concerned with the method of control so much as humanizing its victims. In disordered Earth she even hypothesizes that man might not even be the most intelligent species on the planet. (That honor belongs to Earth's genetically altered pigs.)

illustration by jason courtney

illustration by jason courtney

While some may find it a bit tiresome at times to relive all the ways Ms. Atwood finds our current predicament lacking, excitement levels increase substantially in her vision of what is to come. MaddAddam is a parable, and all parables tend to insist it is the darkest before the dawn. Atwood delights in the breaking down, futiley attempting to resist her own inner desire for an anarchy she finds both horrible and necessary.

Having Crake live over and over again through the eyes of those who knew him is an enticing thought; two sequels may not be enough. What about Crake's barber? Even though Crake's base psychology (revenge) was obvious, he was also a thoughtful God. It's obvious that Margaret Atwood would have better at being God than almost anything or anyone.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording.

"Lost Land" - Alela Diane (mp3)