TV

TV In Which We Risk The Middle Class

Friday, October 13, 2017 at 11:04AM

Friday, October 13, 2017 at 11:04AM

Self-Erosion

by ELEANOR MORROW

Chance

creators Alexandra Cunningham and Kem Nunn

Hulu

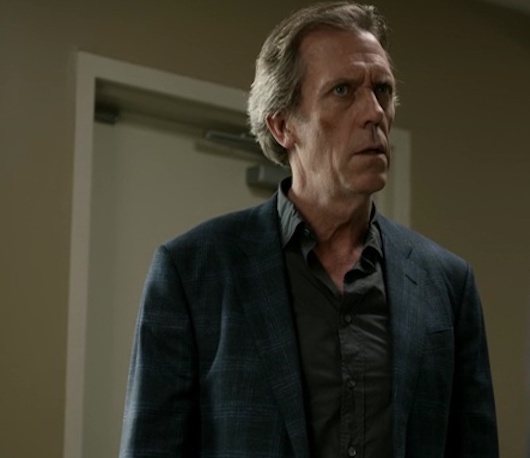

Kem Nunn is the kind of person who just looks wrong in clothing. As therapist Dr. Elden Chance, Hugh Laurie attempts to replicate that basic mien. Hunched over in front of a patient, he resembles a man constrained by a Pullmanesque daemon, being tugged at by all sorts of sources larger than himself. The main inertia acting on him is his massive bald spot, which the second season of Chance draws considerable attention to at every juncture. The point is that while Dr. Chance is steadily, progressively losing his hair, his precisely violent friend 'D' (Ethan Suplee) is completely bald, but full of hair in a variety of other places.

Kem Nunn is the kind of person who just looks wrong in clothing. As therapist Dr. Elden Chance, Hugh Laurie attempts to replicate that basic mien. Hunched over in front of a patient, he resembles a man constrained by a Pullmanesque daemon, being tugged at by all sorts of sources larger than himself. The main inertia acting on him is his massive bald spot, which the second season of Chance draws considerable attention to at every juncture. The point is that while Dr. Chance is steadily, progressively losing his hair, his precisely violent friend 'D' (Ethan Suplee) is completely bald, but full of hair in a variety of other places.

Nunn does not exactly admire therapists. On some level you have to wonder why he has made a show about one. Dr. Chance is completely helpless to affect his patients’ lives, and this second season of Chance hammers this home whenever possible. Dr. Chance is a neuropsychiatrist, one of those terms that in the future will be described retrospectively the way we currently reference shock treatment. Dr. Chance is deeply afraid of the men who torment his patients, and so once he convicts them in his own mind, he allows Darius to threaten or disable their flaccid bodies.

It does not take very long to realize why this is not much of an idea, and having taken this project on with an open mind, it is only the matter of a few afternoons before Dr. Chance realizes it is not the ideal solution. Nor is rehabilitating these monsters at all realistic. His evil deeds begin to consciously and subconsciously rub off on the daughter (Stefania Owen) he shares with his ex–wife. In Chance’s stillborn first season, we watched the good doctor risk everything in his life for Gretchen Mol. This was implausible until she began acting actively freaky, at which point his attraction to her (1) made logical sense and (2) revealed his complete lack of personal integrity.

The novel Chance has this fantastic ending where the possessory nature of the universe took over. Man, or woman, could not be held responsible for their acts when the world was so awry. The general environment of San Francisco informs on this quite broadly. No one can live in this place, Nunn seems to be arguing, without the various economic inequalities of the locale driving you insane or worse. A civilization without a middle class is therefore doomed.

Dressed in sweaters or a jacket and jeans, Nunn has never wanted to be anything like an elite. His modest but brilliant collection of novels, including his magnificent debut Tapping the Source, mines the momentary but exciting genre of surf detective fiction, that which was first gainfully developed by John D. MacDonald. Like MacDonald’s lackadaisical but purposeful protagonist Travis McGee, Dr. Chance runs moral circles around his basic compassion for women who have been abused by men.

San Francisco, then, is the playpen for all morality. Whatever happens there will affect how we deal with the issue of the effect of random chance on every citizen. Other places in the world and in our country reward a certain psychological aspect, but San Francisco can no longer be said to endorse this view. In this abandoned metropolis, a savage immorality is the only healthy way of all-around living.

Eleanor Morrow is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Manhattan.

eleanor morrow,

eleanor morrow,  hugh laurie,

hugh laurie,  kem nunn

kem nunn