FILM

FILM In Which A Convent Remains Our Home Away From Home

Sunday, August 20, 2017 at 11:54AM

Sunday, August 20, 2017 at 11:54AM

Better Half

by ELEANOR MORROW

Black Narcissus

dir. Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger

100 minutes

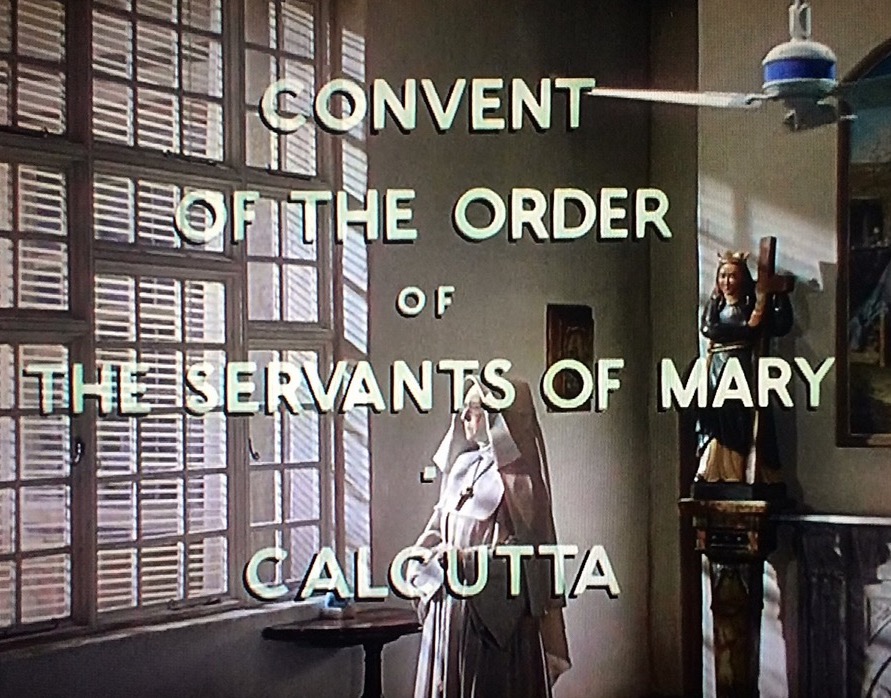

Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) had the good sense to select an order — an Anglican strain of the usual — that demands a renewal of vows once a year. This sort of optional religiosity is a breath of fresh air, for a young woman may learn all sorts of things about herself in a duration of 365 days. Kerr was only 26 when she took on this role as Mother Superior to a tiny convent in the Himalayas in 1947's Black Narcissus. Naturally, she spends most of her time thinking about all the hot sex she used to have, but does not anymore.

Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) had the good sense to select an order — an Anglican strain of the usual — that demands a renewal of vows once a year. This sort of optional religiosity is a breath of fresh air, for a young woman may learn all sorts of things about herself in a duration of 365 days. Kerr was only 26 when she took on this role as Mother Superior to a tiny convent in the Himalayas in 1947's Black Narcissus. Naturally, she spends most of her time thinking about all the hot sex she used to have, but does not anymore.

Shot entirely in England, Black Narcissus is a relatively wretched Indian film, but a substantially more exciting English one. By the improved standards of today, it is wildly racist. Jean Simmons portrays Kanchi, a seventeen year old orphan, in the most unconvincing blackface you will ever see — suggesting that perhaps the film's title was made somewhat tongue-in-cheek by this adaptation.

The best parts of the movie are actually the flashbacks to Deborah Kerr's life before she was a nun. Director Michael Powell was still obsessed with the woman who was his ex-girlfriend by the time Black Narcissus underwent production. Kerr's face is constantly shot in close-up as a matter of necessity; otherwise, she would just be another lithe body in a white habit. When we find Kerr in England, she is a whirling dervish of action, spinning to find her boyfriend Con (Shaun Noble), who seems perpetually out of frame.

The script of Black Narcissus was nothing special, faithfully based as it was on a rather turgid novel. Powell papers over this completely, shooting long sequences with music and limited dialogue, and pumping up the flashbacks whenever the pace starts to flag. (It still does, even in a film only 100 minutes long.) His use of light here is particularly stunning, whether it is the way candles accentuate a growing despair, or how translucent cloth hides the light of the moon. Texture is the only morality left to abandoned people.

As Mr. Dean, the tempting male figure desired by both Sister Clodagh and Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron, Powell's girlfriend at the time), David Farrar almost ruins the entire movie. He is the hairiest screen actor perhaps of his century, which is all to the good, but his entire performance is far too hammy, suggesting more of a parody than a realistic presentation. His shirtless scenes are still rather striking, even if he comes across as n oversized boy in them.

Kerr saves things anyway. The restrictions a nun's habit places on the actor is nothing to this brilliant performer, who utilizes her hands and eyes to communicate what the body cannot. Powell constantly pushes the native wind of the mountains through Sister Clodagh's habit, making her the film's clear Jesus figure. "Work until you're too tired to think of anything else," she tells someone, anyone.

Things begin to fall apart in the Himalayas when the nuns start screaming at a little boy and accuse of each other of being overly hysterical. The shocking twist of Black Narcissus occurs entirely in the past — the flashbacks Sister Clodagh reminisces about so fondly are merely memories of a guy who never gave two shits about her. "Now I seem to be living through the struggle again," she tells Mr. Dean without looking at him. He might as well not be there at all.

The film's bravura sequence occurs at its end. Kathleen Bryon's Sister Ruth has been driven insane by jealousy — her eyes are tinged with opiates, or maybe this is only an exaggerated version of herself. She has been spurned by a certain Mr. Dean, which was probably foreseeable given that the man she loved never blessed her with the knowledge of his first name. He decides to send her to Darjeeling, a proper distance, but instead she returns to the convent in order to murder Deborah Kerr. Ruth cannot even properly accomplish that.

In this dramatic, sunset-tinged manumission, Kerr climbs back up from the cliff's precipice and tosses Ruth off to her death. She pretends to be surprised as her charge shatters in the forest below. The feeling is not mutual. We all knew this was coming.

Eleanor Morrow is the senior contributor to This Recording.