TV

TV In Which We Have Returned To The Red Room Of Our Youth

Thursday, August 10, 2017 at 9:11AM

Thursday, August 10, 2017 at 9:11AM

Place to Hide

by ELEANOR MORROW

Twin Peaks: The Return

creators Mark Frost & David Lynch

Showtime

The only place you know is real is the town where you live. The bank, the trailer park, the diner. The police station, the bed and breakfast, the residents that only get older, never younger. Oh god, the residents. Recently I found myself watching older episodes of Twin Peaks. Although they are in general sloppier and substantially less satisfying than the precise brilliance of Twin Peaks: The Return, probably the best thing that has ever aired on American television, they are not really all that different.

The only place you know is real is the town where you live. The bank, the trailer park, the diner. The police station, the bed and breakfast, the residents that only get older, never younger. Oh god, the residents. Recently I found myself watching older episodes of Twin Peaks. Although they are in general sloppier and substantially less satisfying than the precise brilliance of Twin Peaks: The Return, probably the best thing that has ever aired on American television, they are not really all that different.

The major difference is the subplots. In the original Twin Peaks, the subplots were sort of a lazy, soapy gauze around the main storyline. In Twin Peaks: The Return, they are merely reflections of something we can never exactly see. Never in my wildest dreams did I believe that David Lynch would feature Kyle MacLachlan as a mentally deficient shell who merely echoes back whatever the people around him say, and that it would work for a solid fifteen episodes.

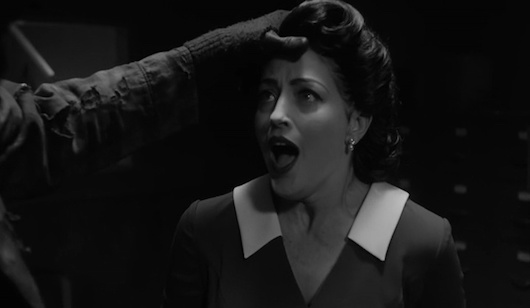

In a season full of haunting moments, probably the most haunting were the twin delusions of Audrey Horne (Sherilyn Fenn). In her fever dream, which is never explained or put into context, she is confined in her home with her husband Charles (the fantastic Clark Middleton). She wants to leave, but she cannot. She asks her husband if he has ever felt like he is two people. He tells her that he has not, that he has always been himself and knew this to be true.

Mental illness has always been major theme of Twin Peaks. The idea that there is something about our own personalities that we can recover from, like an illness, is not only fascinating, it is wildly optimistic. Whether or not this can be accomplished in our hometown is a matter of significant question in Twin Peaks: The Return.

I never found the original Twin Peaks alike to darkest noir, probably because of television broadcast standards at the time. Whenever it delved into the particulars of various drug crimes or the seedier elements, it felt so goofy or scary, but not at the level of darkness we have been experiencing this summer. Kyle MacLachan's "other" performance as Evil Agent Cooper is ridiculous when he assume the echoes of the earlier character, serious enough to give us a rotund chill. Lynch goes for a lot of laughs here as well, such as the decisive moment where Cooper kills a man with a single punch to the face. Watching all Lynch's favorite actors cheering an arm-wrestling battle on was hysterical, but the interrogation scene that follows was more chilling than amusing.

Why are you not watching Twin Peaks: The Return? What excuse could you possibly have? Your response to my entreaty falls on deaf ears.

Forget the production design, which is one of its kind and will be reproduced forever. Ignore the sound design, which Lynch handles himself and makes listening to Twin Peaks: The Return the best radio play in the history of mankind. I can't think of another production that has ever had the sheer volume of perfect acting performances Lynch coaxes out of his regulars and newcomers on Twin Peaks: The Return.

Particularly amazing are Jennifer Jason Leigh, who is so suited to the dialogue of Lynch and Frost, Jane Adams, who deserves a spinoff of sorts, Robert Knepper's bungling mafioso, and Fenn herself, who probably should have had a much better career than she did.

Traded and exchanged between this massive cast is a story ostensibly supernatural, but a tale which at its heart is more of a MacGuffin than ever. It does not really matter who evil inhabits, or the nature of evil itself — the question is of how to deal with this eternal challenge. Lynch passes along as few answers as ever, though he gives us the courtesy of a few, bracing moments as relief in the mind-blowing musical performances that conclude most episodes.

This last week, James Marshall performed David Lynch and composer Angelo Badalamenti's marvelous hymn "Just You" while a woman looked on and cried. It told the story of several conversations over the course of many years. It completely removes a self-reflective irony, such a recurrent plague on both American comedy and drama over the last decade, and shows the world for how sincere it is. The town that knew you before you knew yourself, and you hated it for that. Years passed before you realized.

Eleanor Morrow is the senior contributor to This Recording.

david lynch,

david lynch,  eleanor morrow,

eleanor morrow,  twin peaks

twin peaks