TV

TV In Which We Sincerely Believe We Do Not Belong

Monday, September 18, 2017 at 8:00AM

Monday, September 18, 2017 at 8:00AM

Self-Mining

by ELEANOR MORROW

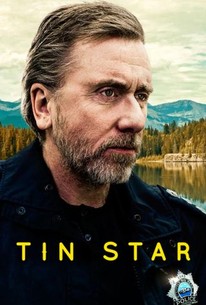

Tin Star

creator Rowand Joffe

Sky

In Tin Star, Jim Worth (Tim Roth) is a London police officer who relocates to a mining town in British Columbia with his wife Angela (Genevieve O'Reilly), his daughter Anna (Abigail Lawrie) and his son Peter (Rupert Turnbull). At the conclusion of the show's tumultuous first episode, an assassin approaches the family at a sinister Calgary gas station. He fires a bullet at Jim's head from a distance of seven feet. Instinctively, Jim ducks, and the shell explodes his five year old son's head. Fragments of the boy's skull impact on his mother's cranium, and she enters in a coma.

In Tin Star, Jim Worth (Tim Roth) is a London police officer who relocates to a mining town in British Columbia with his wife Angela (Genevieve O'Reilly), his daughter Anna (Abigail Lawrie) and his son Peter (Rupert Turnbull). At the conclusion of the show's tumultuous first episode, an assassin approaches the family at a sinister Calgary gas station. He fires a bullet at Jim's head from a distance of seven feet. Instinctively, Jim ducks, and the shell explodes his five year old son's head. Fragments of the boy's skull impact on his mother's cranium, and she enters in a coma.

Jim is a recovering alcoholic, and it is not one night later that he finds himself in a bar. Tin Star creator Rowand Joffe gives us a hearty close-up of the heavenly whiskey that Sheriff Worth desires more than anything in his turgid little life. Everything in his world is categorically easier to abandon than alcohol – which is not to say he is not going to fail his family. Just that it will be hard.

Jim's enemies do not really have sufficient reason to want him or his son dead. They are representatives of the oil concern which has infilfrated the town. The idea that oil companies would have to resort to murder to get their way when they can simply purchase everything in sight is somewhat implausible, but who cares? Tin Star is more a pure revenge fantasy, meant to bring Jekyll's story into a Western forum. It has to be a fantasy – I mean, I can't rationally believe in a rural Canadian town where everyone in it is a different type of asshole.

Christina Hendricks plays Elizabeth Bradshaw, a representative of that oil company. Hendricks grew up in the Pacific Northwest, although you would not really know it. I think her father was British, which makes sense with her coloring. She looks absolutely tiny in this, having eradicated any of the voluptuousness which might lend a sympathetic tint to this merciless. character. She is not so much a villain as an embodiment of a lack of personal morality.

Jim's daughter Anna is drawn to alcohol, and one of the most affecting scenes in the show's opening episodes has her chugging down the various components of a motel mini-bar. "I want to be an archaeologist," she tells her father, and this fortune-telling strikes us as wildly off-base. Jim himself has nothing in the way of hobbies or passions – that was what drinking was for. His job enables him to practice the only skill he has – the distribution of violence, and to mete it out for somewhat rational reasons.

He is completely disconnected from modernity. It is what happens to those of us who, as we get older, neglect to manifest a regular discernment of what makes society itself. Such people often change their surroundings, since doing so gives them a reasonable excuse for feeling lost. There is no such get-out-of-jail free card when we are surrounded with those we know, and those who know us. It is better to be in the wilderness, where you can sincerely believe you do not belong. You will be right.

Eleanor Morrow is the senior contributor to This Recording.