FILM

FILM In Which We Leave New York In A Panic

Monday, September 11, 2017 at 9:04AM

Monday, September 11, 2017 at 9:04AM

The Mistress of Fevre-Berthier

by ALEX CARNEVALE

In 1958 New York was a dark city. Much more so than Paris, I remember that from the window of my room on the ninth floor, looking out over 85th Street, I couldn't see what was going on below. I could hear cars passing and see their headlights, but I couldn't see the street. New York is as dark as it is beautiful.

In 1958 New York was a dark city. Much more so than Paris, I remember that from the window of my room on the ninth floor, looking out over 85th Street, I couldn't see what was going on below. I could hear cars passing and see their headlights, but I couldn't see the street. New York is as dark as it is beautiful.

At the age of forty-two, Jean-Pierre Melville went to a New York he knew from the movies. He had just discarded a film-in-progress that would never be released — a spy movie featuring frequent collaborator Pierre Grasset. His new project detailed the story of a French cabinet member's death in his girlfriend's apartment. He had shot twenty minutes of it when Charles de Gaulle came to power in 1958, forcing Melville to reconceive of the project in America, though the interiors for Two Men in Manhattan would be filmed back in Paris.

As de Tocquevilles go, there is none better. Although Two Men in Manhattan is something of a disaster as a motion picture with an engaging plot, it is better conceived as a documentary of New York in the late fifties, with a particular focus on the sorts of women that Melville met in the city.

Some of the many women that Moreau (Melville, in his only starring role) and Delmas (Pierre Grasset) meet are lesbians, many are non-white, and most have tremendously large breasts. "This seems to be the American ideal of beauty," Melville told Rui Nogueira. "You had the feeling that Americans were suffering from a mammary complex and still needed to be breast-fed. It was very disagreeable, repugnant even."

Watching Two Men in Manhattan today, you come to the sinking conclusion that very little has changed. The entire film takes place two days before Christmas, and Rockefeller Center looks exactly the same as it does every year. New York is dark, vast and nearly infinite in Melville's conception. It took him a few weeks to learn what took me years and years. If only I could see as Jean-Pierre did; that is, everything at once.

Photographed by Michael Shrayer, this New York is rooms and elevators, small and tinnier. Lights passed through surfaces translucent, then mysteriously opaque. Sound bounces around and begs to be removed. Suddenly Two Men in Manhattan becomes unbearably loud with the sound of horns, before transforming, not a moment too soon, into the elegiac ballad you were never expecting. Along with the proliferation of rats, it is really enough to begin to loathe the place.

Grasset's character is a lothario member of the paparazzi. About halfway through the film, he and Moreau find the young girlfriend of the diplomat in Roosevelt Hospital. She has tried to kill herself by slashing her wrists, and she lies helpless and alone in bed. Moreau enters first to try to find out what has happened, but when he cannot get the information he wants, he sends in his less scrupulous friend.

This moment of violation, of utter violence, is awful to witness. But Melville is suggesting that as indecent as it is, this is nothing compared to what we do to ourselves. Jean-Pierre repudiated Two Men in Manhattan many times, and the dialogue in the film appears to have been devised in a rush. As an actor, Melville comes across like a minimalist eunuch. Unfortunately, he lacked the training to conceive of his priggish character as anything but a schlub. Ashamed, he never appeared in front of the camera again.

By making both of his protagonists unlikeable journalists, Melville indicted his critics. But in a weird way, this was the right choice for Two Men in Manhattan, since it makes the diverse roster of women that the men query throughout into the secret heroes of the film. All of the women lie to these men they barely know, since it is the only way to protect themselves from the patriarchal harm Moreau and Delmas represent.

Built into this portrayal is Melville's definitive brief on the opposite sex. Without saying anything or stating it outright, Two Men in Manhattan is concerned with what Melville admires about women, and also what he feels is not present in individuals of his own sex. Dispensing with conventional wisdom and stereotype, Melville finds these feminine human beings have all sorts of qualities that he is lacking, and cataloguing them would take as long as the film's running time. Crucially, it is not that they are better or worse than men, it is that they less frequently delude themselves about this subject.

I took this lesson to heart. I used to walk by the United Nations building, featured numerous times in Two Men in Manhattan, quite a lot. There is a development site several blocks long not far from the U.N. that has featured a massive pit for as long as I can remember. In China the site would have been developed in a weekend, but here in New York the project never stops oscillating. To prevent people from falling in, a white curtain blocks a stunning view of the East River. God forbid you are ever able to pretend you are anywhere other than where you stand.

My memories of New York are a day in the Central Park Zoo, and standing near that fake castle in the rain. My friends who I loved are still there, well maybe some of them are. Perhaps I'll check when I find the nerve. The subway broke down near Columbia. We all got off, some of us did, others stayed on, waiting to see where the train went. I walked to the top of the park with sweat in my eyes. A fire filled up a trashcan, so I told a doorman. The next day was the Puerto Rican Day Parade.

No time to think about who and what I miss. God gave me a letter, and I walked all the way down Second Avenue and back. Jamie came over to take care of the mice, and went out again. Helping my professor sort through his crowded apartment, his prints. Spring was always the wrong season, smiles were too seductive or not enough. I left her at 72nd Street. When I came back, she was still crying. Now so am I.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. He is a writer living in Los Angeles.

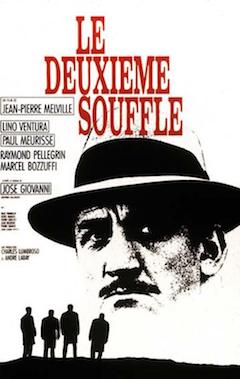

The Greatest Trick Mr. Melville Pulled Was Convincing The World He Didn't Exist

Alain Delon plays a schizophrenic assassin running from his employers and the law

The men and women of the Resistance find a way to survive

Jean-Paul Belmondo's appeal to women knows virtually no bounds

This was the straight-up inspiration for Reservoir Dogs

Lino Ventura is a criminal who knows his life has come to an end

Two or maybe three men in Manhattan