TV

TV In Which We Resleeve Ourselves Into Something More Familiar

Sunday, February 18, 2018 at 8:47PM

Sunday, February 18, 2018 at 8:47PM

Important Men

by ETHAN PETERSON

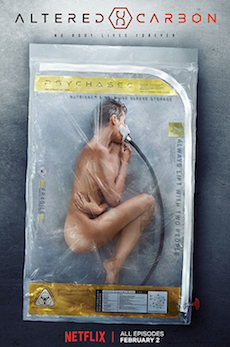

Altered Carbon

creator Laeta Kalogridis

Netflix

In this future story from novelist Richard K. Morgan, we are thrust into a world where anyone can look however they want. That James Purefoy wants to look like James Purefoy makes sense on its face, but who would want to look like Joel Kinnaman? Joel Kinnaman looks like the "before" picture in one of those old advertisements in Archie comics, the shrimp who would get beat up at the beach or a dinner party (see below). Kinnaman explains fairly early on that he is an Envoy, which is some kind of soldier. The basic point we are meant to get across about this individual is this: he has a rich and storied history, and could tell you things of which you are probably unaware.

In this future story from novelist Richard K. Morgan, we are thrust into a world where anyone can look however they want. That James Purefoy wants to look like James Purefoy makes sense on its face, but who would want to look like Joel Kinnaman? Joel Kinnaman looks like the "before" picture in one of those old advertisements in Archie comics, the shrimp who would get beat up at the beach or a dinner party (see below). Kinnaman explains fairly early on that he is an Envoy, which is some kind of soldier. The basic point we are meant to get across about this individual is this: he has a rich and storied history, and could tell you things of which you are probably unaware.

Instead of doing so, Kinnaman's version of Takeshi Kovacs is only interesting when he is thinking about killing himself. It would have been an important moment to have a suicidal main character if I already didn't want to cut myself when I saw Matt Damon's goofy face.

It was a mistake to cast Joel Kinnaman in this role for so many reasons:

1) He admits he has never brushed his teeth.

1) He admits he has never brushed his teeth.

2) His cloying overacting may have singlehandedly torpedoed House of Cards in retrospect, sparking a sexual harassment revolution.

3) The only time he ever had chemistry with a co-star was in The Killing, and that co-star was ostensibly a corpse,

4) His penis is shaped like a soda can and from some angles cannot be viewed by the human eye.

5) His transparent overtraining to look like a soldier (what a fucking Christian Bale wannabe) makes him have the practical dimensions of the star of Where's Waldo,

6) He is Asian when he dies in the show's opening scene, and when he wakes up, he's Joel Kinnaman. We lost so much just right there.

There comes a point in your life when you realize you're dating yourself. In real life, the Swedish-born Kinnaman is married to a tattoo artist. Her skin resembles a sheet of paper that's been written over too many times.

Kinnaman's main antagonist is a Latina police officer named Kristin (Martha Higareda). Kristin is pretty tiny, and the two have so many scenes together that it is very awkward to see them both in the same frame. Perhaps wisely, creator Laeta Kalogridis puts as much focus on the surrounding mise-en-scene as she can. (She even refers to it as mise-en-scene.) The future, in Morgan's imagining, is basically like now except some people can live forever if they have enough money. What they are really paying for is for a version of themselves to be hosted on satellite and beamed back into a new cortical stack should they be murdered.

This has in fact happened to Mr. Bancroft (The slovenly James Purefoy, who has the biggest mole imaginable, gross, disgusting). He wants Kovacs to solve the murder, but despite his ample resources and connections within the resleeving industry, he cannot find an Asian body for his private detective to inhabit. That this is racist is indisputable, so Altered Carbon papers over it with a bunch of roles for African-Americans in which they play second bananas or omnipotent, advisory god figures.

If you think I'm trying to discourage you from watching Altered Carbon, think again. There may in fact be a future, or even a present where someone would want to look like Joel Kinnaman - all gangly and soda-canesque. I'm pretty sure Kinnaman has ruined everything he has ever been in. I don't even remember who he was in Suicide Squad, which is probably for the best.

The worst part of his casting is that Altered Carbon would basically be John Wick if Keanu Reeves would do television. In any case, an actual actor was required for the role.

Ethan Peterson is the senior contributor to This Recording.