FILM

FILM « In Which We Recognize Ryan Gosling For A Reason »

Wednesday, January 10, 2018 at 12:16PM

Wednesday, January 10, 2018 at 12:16PM

Gestalt

by ETHAN PETERSON

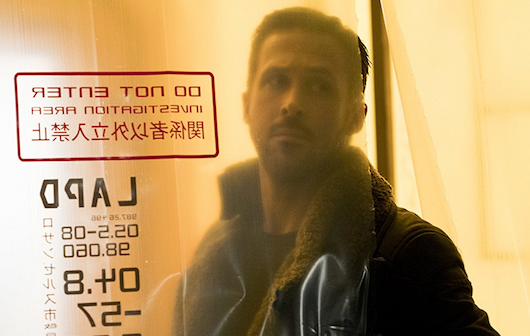

Blade Runner 2049

dir. Denis Villeneuve

161 minutes

Blade Runner 2049 begins when K (Ryan Gosling) kills a robot on the robot’s farm, which is owned by Wallace (Jared Leto) who invents robots for a living and is probably a robot himself. (K is also a robot, the most handsome robot imaginable.) If you just take as a given that everyone is a robot in Blade Runner 2049, you will be fully correct most of the time, since the film has taken the step of eliminating the distinction between humans and automatons with their own consciousness, if there ever existed one in the first place.

Blade Runner 2049 begins when K (Ryan Gosling) kills a robot on the robot’s farm, which is owned by Wallace (Jared Leto) who invents robots for a living and is probably a robot himself. (K is also a robot, the most handsome robot imaginable.) If you just take as a given that everyone is a robot in Blade Runner 2049, you will be fully correct most of the time, since the film has taken the step of eliminating the distinction between humans and automatons with their own consciousness, if there ever existed one in the first place.

Gosling reports back to his boss at the LAPD, Madam, who is played by Robin Wright Penn. All of Wright Penn’s recent roles have involved an unfeelingness, so I guess this is why Villeneuve cast her in this familiar part. This is a general problem across Blade Runner 2049 – when actors are too readily identified with their roles, we substitute our knowledge of their characteristics for ones that may be present in the drama.

Villeneuve leans on this heavily, since there is not a lot here in the way of character development in general. In Blade Runner 2049, a crooked businessman is a crooked businessman, a fixer and forger is a decent and hearty sort, and a prostitute sells her body for a reason.

At the site of the killing, Gosling finds the remains of Rachael, a robot from the first movie. The skeleton indicates she was pregnant. Wright Penn’s character wants to find and destroy the child for the implications a pregnant machine would bring, whereas Wallace wants to find a way to breed robots since it is too expensive to construct them on the interplanetary scale he requires. The implication is that neither solution is definitively correct, since both approaches involve the underlying assumption that an articially constructed person is not a person. “You got along just fine without one,” Penn tells Gosling. He responds, “Without what?” “A soul.”

This kind of hamfisted obviousness was missing from Ridley Scott’s original, as was the concept of an automaton as a kind of depressed person who believes or she is missing something because they are not fully human. The date of birth of the robot reminds Gosling of an implanted memory he has – in short, he is running from other boys at an orphanage, and he has to hide a wooden horse from them. On the bottom of the wooden horse is the same date as the one on the birthed robot.

Gosling perhaps reasonably assumes that he is the birthed robot, who was given over to an orphanage. In order to be sure, he visits the creator of the memory to see if it is a real memory or a fake one. When she looks at it, she says it is real. But she is lying to him, because she is actually the first and only robot baby, and she is in hiding. Her father is Deckard (Harrison Ford), and for some reason he is living in a decimated Las Vegas, where some kind of electromagnetic bomb went off.

Gosling is usually a treat to watch. He has great facial expressions, and an engagingly repressed enthusiasm for life. In casting him as a robot, Villenueve goes to great lengths to preserve these strengths, even though the natural limitations of the role are at odds with them. We don’t realize how much Gosling seems to strain at these restrictions until we meet Deckard inhabiting an empty casino where videos of Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra cycle from before the blackout.

Mr. Ford is not much of a pilot, but he is tailor made for this role. Even his expressions of what, on the surface, appear to be genuine human emotion contain an innate reserve that we often call dignity. In contrast, Gosling’s anguish is of a more base, helpless variety. There is something powerful in the contrast of the two performances, but it is only natural that we gravitate as viewers to the one that places our species in the most positive light.

Villeneuve is a slick director with a gift for composition and a handle on what is required in successful art direction. There are lots of neat touches and update to the genre defining look that Blade Runner introduced when it bombed at theaters in 1982. Even some of the same locations get a makeover, although for the most part the grittiness and verite of the original is missing here, replaced by the emptying aftereffects of climate change.

You could probably make an infinite number of Blade Runner movies on roughly the same themes — how technology has the potential to continue the objectification of women, pets, and racial minorities, how replacing humans with AIs makes no tangible difference to life as it is generally constructed, how every living thing demands to be treated with a certain amount of respect no matter who or what it came from. All these messages are timeless, but in Blade Runner 2049, they start to feel a bit closed off to us. Should the future be so concrete?

Ethan Peterson is the reviews editor of This Recording.

Reader Comments