FILM

FILM « In Which She Thought She Belonged In The Arms Of A Man »

Friday, September 1, 2017 at 8:47AM

Friday, September 1, 2017 at 8:47AM This is the third in a series examining the films of the French director Jean-Pierre Melville.

Father Don Juan

by ELEANOR MORROW

Everyone has the right to be what he is and believe what he likes.

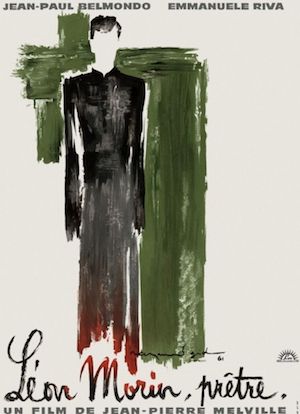

Barny (Emmanuelle Riva) is a lesbian who feels guilt/happiness after her communist husband's death. Her half-orphaned daughter is baptized, because otherwise the girl's Jewish father would mark her for the Nazis, in a French town abandoned by God. As she works her office job, a gorgeous woman there consistently stands behind her, brushing her breasts against the back of Barny's head. This stimulation, and the eye-contact that occurs between these moments of orgasmic, incidental touching, drive her to a local priest (Jean-Paul Belmondo). Such is the plot of Léon Morin, Priest.

Barny (Emmanuelle Riva) is a lesbian who feels guilt/happiness after her communist husband's death. Her half-orphaned daughter is baptized, because otherwise the girl's Jewish father would mark her for the Nazis, in a French town abandoned by God. As she works her office job, a gorgeous woman there consistently stands behind her, brushing her breasts against the back of Barny's head. This stimulation, and the eye-contact that occurs between these moments of orgasmic, incidental touching, drive her to a local priest (Jean-Paul Belmondo). Such is the plot of Léon Morin, Priest.

Jean-Pierre Melville was very unhappy with the reception to 1959's Two Men in Manhattan, the only film he ever made that featured himself in a leading role. Léon Morin, Priest was based on a well-known novel by Beatrix Beck, who was pleased with Melville's rendition of her work. Melville chose the project because Belmondo, the leading young star of the French cinema, was bound to sell tickets if only he might be cast as a sexy priest. "You should paint your toenails," he tells Barny in one ludicrous scene.

It is very surprising that the Catholic Church praised Melville to high heaven for this motion picture. Léon Morin's parishioners are seemingly all attractive young women whose lives in some way have been corrupted by the German and Italian occupation of France. The film mostly consists of long conversations Barny has with Father Morin – this parade of stars was a necessity for audiences that came to see this unlikely, never consummated romance.

Determined to make a commercial hit, Melville (who was actually in the Resistance) was at his most subtle and subversive on this project. Watching Léon Morin, Priest, you feel that only Melville could have made an art-house movie as a ticket-selling blockbuster. Few people watching the film at the time were in a position to realize how much he was undermining the Catholic religion and, indeed, the concept of faith in general. Ultimately, Barny becomes a Catholic because she confuses her loneliness for a prurient interest in Morin; in reality it is simply an equally impossible iteration of her homosexuality. Despite the fact that it is very difficult to like characters who loathe themselves, Barny is sympathetic for two reasons.

The first is that she is a brave, proud pseudo-Jewish woman who supports the Resistance any way that she can. The second is that she is very beautiful, but she has no idea.

Ensconced in grief because of what has happened to her life and her country, Barny narrates Léon Morin, Priest in the loveliest voiceover in the history of cinema. She sparingly chimes in, never to describe or summarize events, but simply to exist on a perceptual level, and to describe what images could never convey. Riva's throaty chords, mellifluous in Alain Resnais' Hiroshima Mon Amour, melt everything that surrounds them except Morin, who proposes an idea of Catholicism as an all-loving instrument to remedy the wrongness the world cannot help but contain.

Anyone with even the slightest bit of experience with Catholicism knows that this depiction is utter bullshit, and I say that as an admirer of the sect.

As Léon Morin, Priest spirals to its inexorable conclusion, we await the film's final scene – where Barny will finally have to say goodbye to Morin. She tours his soon-to-be abandoned office above the church, where crosses have been ripped down and the piano returned to its original owner. God has left this church in the same fashion as he abandoned France during those years.

Our final glimpse of Father Morin provides an unexpectedly frightening moment. He is posed as the devil, standing guard outside his underground den. It is only that we realize his admonitions to Barny represented a false, tortured hope in Melville's eyes. In actuality, she was perfect before she ever met Morin and convinced herself that the right thing to do was desire a man.

Eleanor Morrow is the senior contributor to This Recording.

Reader Comments