FILM

FILM « In Which We Live Through All Our Actors »

Thursday, August 31, 2017 at 9:25AM

Thursday, August 31, 2017 at 9:25AM This is the second in a series examining the works of the French director Jean-Pierre Melville.

Mr. Black and Mr. Green

by ETHAN PETERSON

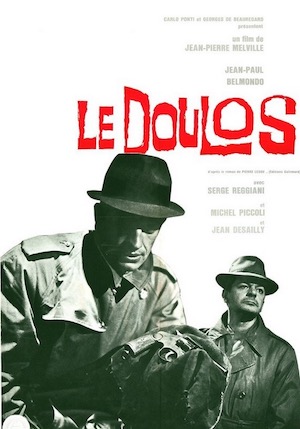

Le Doulos begins with Maurice (Serge Reggiani) returning to Paris on foot in the tracking shot to end all tracking shots. The camera almost never leaves Reggiani's dark face in the film's tragic interiors, but when he is outdoors like in the first moments we view his slight, quick form, writer-director Jean-Pierre Melville gives us a sense of how incidental humanity is to the landscape it inhabits.

Le Doulos begins with Maurice (Serge Reggiani) returning to Paris on foot in the tracking shot to end all tracking shots. The camera almost never leaves Reggiani's dark face in the film's tragic interiors, but when he is outdoors like in the first moments we view his slight, quick form, writer-director Jean-Pierre Melville gives us a sense of how incidental humanity is to the landscape it inhabits.

Maurice has been released from prison, but he has changed a lot since he went inside. His medical condition – an iron deficiency – has become substantially worse. His first act as a free man is a murder. Later, his best friend Silien (Jean-Paul Belmondo) shows up at his apartment and promises various equipment for a robbery Maurice is planning on the home of a rich old man. After Silien leaves the apartment, we see him telephoning his only other friend in the world, Detective Salignari of the local police.

The deceptively fast-paced Le Doulos then segues into one of the most thrilling half-hours in cinema. While Maurice heads off to commit a robbery we know he really does not need to complete, Silien returns to Maurice's apartment, finding girlfriend Thérèse there alone. He beats the shit out of her and ties her to a radiator, all the while wearing the most placid, sociopathic reaction imaginable. This is the scene we turn over in our mind throughout the rest of Le Doulos. It is one thing to overwhelm a woman with violence, but it is another to do it from a place of moral justification.

Later, Silien explains his behavior. Melville flashes back, revisiting the events of film, in the central twist of Le Doulos. This series of reveals seems to explain everything that has happened in a new and more justified light. But a key shot of Silien looking in the mirror suggests there is another possible Silien, another explanation for who he is and why is slapping this woman so hard. Silien's version of events is that Thérèse was the informer, and that he had seen her having a nice lunch with Detective Salignari.

This montage narrated by Silien has always been assumed to be verifiably true. But there are many holes in his account, and we know that Maurice is a gullible listener. Melville uses no music outside of the film's diegesis, and the light jazz that is actually played by a black piano player in a restaurant suggests that we, too, are being taken for a ride. Thérèse is probably innocent.

Quentin Tarantino cited Le Doulos as the main influence on Reservoir Dogs. Like its American twin, Le Doulos is certainly an extremely talkative motion picture, and half of what is being said in any specific scene is likely to be utter bullshit not meant to be taken at face value on the other end of the conversation. Then, suddenly, Melville gives us an unexpectedly tender scene between Silien and his ex-girlfriend Fabienne (Fabienne Dali). Fabienne is the only actual, legitimate person in the entire film, and yet she is completely flattened by the weight of her associations. Her scene with Silien must have been one of Quentin's favorites.

The similarities to Reservoir Dogs are most obvious in the trenchcoats and the similarity in setting. Melville turns Paris into a weirdly-Americanized version of the same. The film's most famous scene, a conversation between Silien and a detective that runs a full ten minutes without a single cut (the boom operator wore all black so as to emit no light that might cause a reflection), occurs in a replica of a New York police station. In many other moments, Melville focuses on anachronisms and a flexibility of design that seems to prefigure the aesthetics of Blade Runner.

As a result, Le Doulos embodies the strange quality of fantasy to it. Belmonde in particular has never been anything close to my favorite actor, too self-contained and himself to inhabit the life of another. Here his unsuitability for the role of stool pigeon makes the film all the more ludicrous, and the effect of seeing him violently beat up a woman is the oddity Melville was going for. It's funny that Le Doulos was eventually released for all audiences in France, since it would merit a full R rating today.

Getting Reggiani for the part of Maurice was key for Melville in making this project, and you can see why. (Reggiani initially demanded Belmonde's role until Melville convinced him otherwise.) He is one of the few small actors that never looks feebly or unimposing despite his size. His dark, Italian looks make him into an alien of the French cinema – there is absolutely no place for him to hide, and running away is a futile gesture. He will always be caught and returned to the prison that is his home. In this noir masterpiece, as in all his films, Melville excels at seeing through the eyes of all his characters. "Making films means being all the actors at once, living other lives," he said later.

Ethan Peterson is the reviews editor of This Recording.

Reader Comments