THE WORLD

THE WORLD In Which We Attempt To Change The Day We Were Born

Friday, July 1, 2016 at 11:33AM

Friday, July 1, 2016 at 11:33AM

Odd Numbers

by HEATHER MCROBIE

You love Jerusalem the way you love your father. You have to, it’s like God. Golden and eternal and looming down, only there are no shadows to hide in when faced with it, not in any quarter. You submit to its logic, its walls weighted with allegory and tiny little tucked-away dreams, scrolls upon scrolls of little insignificances, lost in the stony face of the city, hills like smoke mixing physical geography and parable. Its gates open and close – announced and regularly – but beyond your control. It’d be as useless to resist as it would be to remove the pattern of your fingerprints on your fingers, or change the day you were born. You’re nothing in the face of it – at best, you’re a little unoriginal replica or a conduit that it moves through. It exists, complete and eternal, irrespective of you.

You love Tel Aviv the way sometimes in a café on either side of the Mediterranean you’re the just right temperature already, there is heat and breeze in the right combination already, unholy and earthly and just-right, some shitty music of just the right kind and some faint laughter from teenagers outside, and then at some inexact point in the afternoon you see someone suddenly and – you were complete before, you understand; it’s not that you need anything – and yet you are suddenly blurred in love, in a smudge of watermelon flavour and soft alcoholic edges and the Dopplering mush of music up and down the beach, none of which you needed until it was suddenly there.

Jerusalem is saying never to forget that you alone are just a fragment or scrap and you won’t even understand the enormity of the page you come from. Tel Aviv is saying – through its neon and its Bauhaus buildings, which you don’t need and which don’t need you but just curve and curve and curve – that you don’t need to live in your worst moment forever; that you can construct yourself anew, enamelled and glistening with careless, improbable joy.

Perhaps, too, both are saying to you – do not think of the other half of the sentence. Jerusalem in its achingly solemn eternity, Tel Aviv in its miraculous hurtling to the future, say together, as opposites, as twins – don’t think, just for a moment, what buys this beauty, what’s hidden and erased now, what and who have had to pay for all of this.

This isn’t a story about either Jerusalem or Tel Aviv. It is not really a story anyway. It’s a little exercise in not becoming too enamelled and not making everything a story. It’s difficult to keep things light. It’s difficult not to draw constellations out of an arrangement of lights. This is what I wanted to explain about Tunisia – not golden iconic Jerusalem, not neon miraculous Tel Aviv, but a place as a place, breezily intangible, that wouldn’t ask to be decoded.

23

The summer I was twenty-three I won a writing prize only five other people had entered with a story that grew into a novel, which was published and froze my embarrassingly unformed juvenilia in place out in the world like a pre-historic bug trapped in amber, or like some kind of pinned not-quite-butterfly. I wore a white dress to the book launch and, drunk in front of my Dad for the first time, I told a real grown-up writer that I was wearing white because “because, maybe, maybe this party is like…my wedding, and maybe it’s like, my books will be my children? Maybe…” I trailed off, imprecisely. The real writer and my out-of-place Dad laughed at me as though I was twenty-three and unformed, and I remember I felt ashamed.

25

The summer I was twenty-five I was studying on the same course as this guy, and I moved in with him because I was lost by all the fractures and codes and loaded surnames of where I was. This guy with a specific passport and a specific surname and of origins of no relevance here crucially once threw my clothes out of the window of the apartment we were staying in, and said something about ‘smashing my teeth in’ because of something to do with the length of my skirt and something to do with my passport, and really there is too much that isn’t mine in this story for me to try to explain it. To stop being trapped – in Novi Zagreb, ugly part of a pretty city, miles from the cool of the Croatian coast – festering in the building with this guy I’d once liked and his fists and sudden changes of mood, I made a bargain with him. I’d write his thesis for him if he would leave me the summer alone and unbruised, and let me keep the apartment while I do it.

I was writing my thesis too. July and August were a blur of decoding graffiti on concrete footbridges and my attempts – alternating with my own thesis – to write in the voice of the man who’d left. I felt detached and professional, numb enough to slump by the electric fan every evening and watch the dubbed and dated soap operas and without feeling affinity for one character in particular. I thought I was mastering the art of getting the overview of a situation, though I wasn’t.

My thesis was on writers persecuted by the state, why we need writers, how literature expands our empathy. The thesis of the man who’d once found a cockroach in the apartment and thrown it at me because I took too long coming back from the shops was on the idea there’s no such thing as morality. Once, after he’d left, I walked back from the bakery stocked up on sirnica and individually-sold sachets of ‘Nescafe’, and briefly appreciated this symmetry between my thesis and his. It was more difficult than writing a novel or building something you believe in, trying to write like him – thinking which avenues of arguments his mind wouldn’t walk down, which subtleties he would have smashed through. Bluntly, because I was feeling bruised and needed to nourish myself with anything I could find within me, I liked having to think of which book he wouldn’t have read, how to limit the thesis’s arguments accordingly.

If that sounds unkind and intellectually snobbish, the guy with the surname had had plenty of educational opportunities, and also once spat in my face and called me a whore for speaking to [ ] because [ ] had a passport from [ ] country. Also, he was willing to have someone else do his work for him.

Like many overgrown boys full of anger, he claimed to be a big fan of Nietzsche. I quoted the philosopher in the thesis I was ghost-writing for my freedom, but – as a subtle, feminine act of resistance – I always made sure I did it slightly incorrectly. Just like you can deliberately sew a button on wrong: not so it comes off straight away, but so it will not hold.

At the end of the year what matters isn’t the graduation ceremony – which was Italian in medieval redness and embarrassment, or the party afterwards – which was Southern in an outline of broken glass and Yugo-rock – but just that my thesis on literature and empathy got a higher grade than the Nietzsche-thesis I’d written for him. This simple fact secretly sustained me the whole winter after I came home and tried to find a palatable way to explain this period of my life to old friends.

I no longer feel very ashamed of this. After all, no price is too high to pay for the privilege of owning yourself. Know who said that, overgrown violent boy? Friedrich Nietzsche.

27

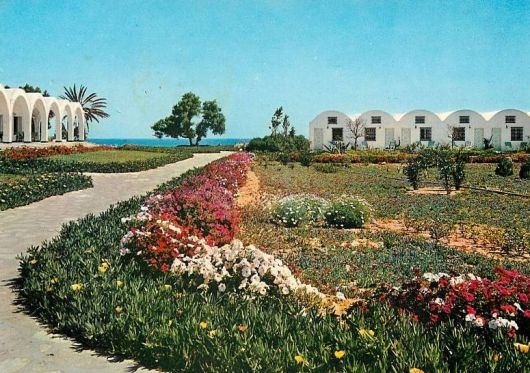

The summer I was twenty-seven I went to Tunisia because I was sort of studying the political situation and recreationally in love with an improbably good-natured visiting French student whose father was from Tunisia though he, my smiling sort-of boyfriend, had never been there himself. When I emailed my friend from neighbouring Libya, she wrote back: ‘Tunisia, so cool so blue so white so nice.'

Although it wasn’t completely spared the pilfering imaginations of colonial-era writers – there’s Flaubert’s Salammbô, which he wrote in an overgrown-boy sulk at the French reception of Madame Bovary; and Andre Gide’s The Immoralist, which treats the country as static backdrop for the Frenchman’s awakening to bourgeois hypocrisies – Tunisia at least wasn’t subjected to the same malignant obsession that France held for Algeria. It was colonised, it was abused, of course, but as it wasn’t anointed as the jewel in the delusion crown of imperial conceit, it could, it seemed, sometimes, just quietly be. I’d learned in the ugly part of beautiful Zagreb that there are few benefits to being an abuser’s chosen object of fixation. Tunisia was comfortable as a country among countries, not stewing in the story of itself. That summer the visiting student and I drank in the Salons de thes and ate makrout and swam and talked about going to Libya but of course weren’t going to Libya, Tunisia was cool and blue and fresh and smelled of jasmine and its revolutionary cry had been for ‘karama’, dignity, an unembellished, unassuming plea.

There were few ‘isms’ and factions in the newspapers, not the political Rubik’s cube of the international arena or the aching fault-lines that split on either side of here, the demand had been the way someone just gives you a look when you’re being unreasonable and you stop being obnoxious. It’s a beautiful word, ‘karama’, because what can you say in the face of someone asking for dignity? It just says, don’t be unreasonable.

Don’t be unreasonable, just go to swim in the sea, make more makrout, let’s not argue, why does it matter, come to bed, never mind we’ll go another day, go to Carthage if you want but these aren’t ruins like Jerusalem’s, electric with live history, these are just beautiful things to be set on the table of a mind next to jasmine and blue-and-white-painted streets. Since I thought of this summer as the French student’s story – visiting his father’s country, seeing the food he’d eaten at home at street vendor stalls, the town south of Tunis that had his surname – I didn’t read meaning into everything. I’d sometimes seek significance in things on his behalf, point out a phrase he’d use that was also spoken here or a repeating pattern in the architecture, and he’d say “but why does it matter?” and it wasn’t mine to make matter or not.

21

I didn’t always know this about places and people and things and languages. The summer I was twenty one I’d gone alone to Israel, and though I didn’t catch Jerusalem Syndrome or get drafted into one of the cults comprised of lost backpackers, in my aloneness and my twenty-one-ness I read everything into everything, in every way all at once until it exploded meaning, by which I mean I think I became unwell, in a way that didn’t get cured until the summer six years later when I was happy.

For the first few days I was just practicing the alphabet and practicing how to be alone. But soon the dead sea scrolls were speaking to the synagogue from Kerala that had been dismantled in India and shipped across an ocean, to be rehoused in a national museum, the great trade routes of empires were springing up in my mind like a global cat’s cradle that I had to consciously hold in place at all times and mustn’t ever let slip, the signs of every newspaper reporting every event in every adjacent country, the languages whose alphabets were cousins of each other, the histories upon histories, each event ricocheting off each other, each genealogy of reminiscence, each side of each story and each collective memory all at once, languages I hadn’t heard of that suddenly I needed to know – who knew about Phoenician, where can I study Assyrian, where can I study all the ways these all interlink and all at once speak to each other. All the little hurtling pollen of history landing on and blossoming in the Biblical and futuristic present – golden Jerusalem and glistening Tel Aviv together – I lay awake at night with notebooks for practicing alphabets and with several books open but not reading any of them because I didn’t know how I would fit everything into my mind all at once so that it was complete.

I think this is what going mad is like, more than thinking a book launch is like a wedding because your unwritten books are like unborn children, or like writing someone else’s work for them to put their name on, or choosing to love a completely inappropriate person, although none of those are very wise choices. The French visiting student would sometimes say to me when I was thinking through something I was studying or writing “but why does it matter? It doesn’t matter, okay.” I had rational views about how the revolution might turn out, based on the newspapers I’d developed the habit of reading, the -isms and factions I’d learned to trade in, but emotionally the idea grew that it works best when a place is a place, so cool so blue so white so nice, and with none of the colours or the names too painfully heavy with meaning.

+

If this story wasn’t about growing up exactly it was about an un-stitching from how you’ve threaded yourself into the codes of the world too intensely. Or a little loosening from that quest to mythologise everything around you – load every name and letter and alphabet and dress and swinging shop-sign and little symmetries of hand-movements of the person sitting opposite you and the major and minor notes struck every time a person laughs and every diacritic and every birdsong or mobile phone tone or date of email address and every airplane ticket and every geographical point and every funeral hymn and every goodbye and every beginning with this weight. It’s very hard to be unsymbolic, not see everything as part of its own language, with a grammar you could learn if you just applied yourself more completely.

It should be easy. For every constellation you make there’s a pattern-less un-remarkableness that you could draw just as easily, if you chose to, or chose not to choose. The summer I was twenty-two I photocopied in an office and baked carrot cake but not very much, the summer I was twenty-four I wrote a bit but not a lot, I don’t remember anything that happened the summer I was twenty-six and I just wasted this whole year I’ve been twenty-eight vaguely thinking about what it would be like to kiss someone I’m not completely sure I’d want to kiss anyway. There don’t have to be patterns. What contentment could come from no longer looking for them, even just for a while.

Heather McRobie is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a novelist living in London. She last wrote in these pages about Ivy's girls. She twitters here and tumbls here.