MUSIC

MUSIC In Which It Was All A Means of Divination

Tuesday, August 13, 2013 at 12:55PM

Tuesday, August 13, 2013 at 12:55PM

A Grand Alchemical Ambition

by HELEN SCHUMACHER

You can find in America a place where houses are built from the remains of shipwrecks and wedding bands are cast from railroad spikes, where people welcome you with a sneer instead of a smile, and where a wooden gallows casts its shadow across the town square. I found my way here late, having returned home after a night of drinking with that downtrodden feeling restless inside of me, when I listened for the first time to Buell Kazee’s version of “The Wagoner’s Lad,” a song that begins with the verse:

Oh, hard is the fortune of all woman kind

She's always controlled, she's always confined

Controlled by her parents until she's a wife

A slave to her husband the rest of her life

It was not a sentiment I expected to find in an antediluvian ballad. And sung as it was in Kazee’s lonesome Appalachian moan, I was profoundly affected. I listened to that track, and another performed by Kazee, “The Butcher Boy,” over and over until it was near dawn, feeling the odd comfort of a bittersweet sisterhood. The mayor of this bleak place I had ended up in was a man named Harry Everett Smith. He was the person responsible for including the Kazee tracks on the compilation I had been listening to — the Anthology of American Folk Music.

In 1951 Smith moved to New York City. As was typical, he was broke when he arrived on the East Coast and contacted Moses Asch, who had recently started the Folkways imprint, with the hope of selling him part of his record collection. An avid collector of obscure records since his early teens, the now 28-year-old Smith had a collection of recordings numbering in the thousands. Asch was intrigued by Smith’s collection, but instead of purchasing part of it, he commissioned Smith to curate what would become the Anthology of American Folk Music — an 84-song collection that played a crucial role in the folk revival for the 1950s and ‘60s. At the time he was compiling the Anthology, Smith was reading Plato, an inspiration he recounts in a 1969 interview: “I felt social changes would result from it. I’d been reading Plato’s Republic. He’s jabbering on about music, how you have to be careful about changing the music because it might upset or destroy the government.” By serving as inspiration for the protest songs of the era, the Anthology did indeed contribute to important social change.

It wasn’t just what Smith put on the Anthology that made it a subversive spellbook, but how. He arranged the songs — from the Devil’s whistle of “faaa-dita-la-dita-la-daaay” relayed by Bill and Belle Reed to the rounds of “We thank the Lord” of the Alabama Sacred Harp Singers and back to the effusive “Kill yourself!” whoop of Uncle Dave Macon — so that themes of suicide and salvation looped around a Möbius strip of red, white, and blue bunting. Smith assembled tracks so as to erase any context of race, gender, and education, and he omitted these kind of biographical details from the album’s liner notes. “It took years before anybody discovered that Mississippi John Hurt wasn’t a hillbilly,” Smith said. It took several months for me to realize that Buell Kazee wasn’t a woman. With no gender context for the name Buell and given the quality of the old recording, Kazee had become the person I needed to hear sing what had registered as a proto-feminist ballad — a woman.

The celestial monochord being played by the hand of God that Smith used for the cover of the Anthology of American Folk Music

The celestial monochord being played by the hand of God that Smith used for the cover of the Anthology of American Folk Music

In his book on Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes, The Old, Weird America, Greil Marcus wrote of Smith’s codex, “The Anthology was a mystery — an insistence that against every assurance to the contrary, America was itself a mystery. As a mystery, though, the Anthology was disguised as a textbook; it was an occult document disguised as an academic treatise on stylistic shifts within an archaic musicology.” The Anthology of American Folk Music was exactly the kind of arcane catalog you would expect to be produced by a man who claimed to be the son of infamous occultist Aleister Crowley and Anastasia Romanov, youngest daughter of the last Russian czar who was executed by the Bolsheviks.

Recording a Lummi ceremony in 1942

Recording a Lummi ceremony in 1942

Another (more likely true) claim from Smith about his childhood was that when he turned 12 his father gave him a blacksmith shop and told him, “You must perform that magic feat which no one in the history of the world has yet performed: the conversion of lead into gold.” This father was a Freemason who worked a variety of jobs in the Pacific Northwest salmon-fishing industry and was married to a woman who worked as a Lummi Indian teacher. They were theosophists and encouraged their son’s interests in the unusual. The elder Smith also had his son build models of Edison’s light bulb and Bell’s telephone in his blacksmith shop. His mother’s work with the area’s Native communities inspired Smith to document their culture. On self-modified equipment, he recorded ceremonies and songs, developed a notational system for translating their language, and collected artifacts (later repatriated) — all while still a high school student. This was the beginning of Smith’s lifelong quest to document and arrange the different permutations of culture as a means to esoteric enlightenment.

The common understanding of alchemy is that it’s the study of turning lead into gold. But this fabled ability, known as the philosopher’s stone, is only one facet of alchemy, which is more philosophical tradition than bunk science. Alchemy is in part physical transmutation, of base metals into noble ones, but even that is said by Hermetics to be symbolic of the greater aspect of the study, which is spiritual transmutation via purification processes, or to bring the body and mind to perfection, to accomplish the Magnum Opus.

Still from Mirror Abstractions, 1957

Still from Mirror Abstractions, 1957

While the Anthology of American Folk Music was a Magnum Opus (or Great Work) in its own right, it was also just one example of Smith’s grand alchemical ambition. Through his documenting and arranging, he hoped to uncover universal patterns and with them a deeper understanding of all human creation. There was his paper airplane collection, assembled over a 20-year period from the playgrounds and streets of New York and annotated with the date and location found for later analysis, and his research into string figures, a storytelling method he considered a global form of expression. During a stint at a Bowery homeless shelter, he made audio recordings of the snoring sounds of his vagabond bunkmates. For Smith it was all a means of divination. He elevated documenting and arranging to a ritualized process — as the preparation for the mystery of transmutation to occur. It became a trademark, particularly in his film work.

Smith's string figures

Smith's string figures

Smith began his experimentations in filmmaking while living in Berkeley. He moved there after dropping out of his anthropology studies at the University of Washington and quickly fell in with the 1940s bohemian milieu. His works were drug-enhanced experimentations in synesthesia that attempted to unite the experiences of hearing and seeing. These experimentations included screenings in San Francisco’s Fillmore district where jazz musicians like Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie would improvise a soundtrack according to Smith’s color projections. Inspired by painters like Kandinsky, Smith considered synesthesia a mystical correspondence between the senses. Exemplary of his Hermetic assemblages was his Film #12: Heaven and Earth Magic, a story of a heroine who incurs a toothache after the loss of a valuable watermelon. The dialogue-less film was primarily made from collaged catalog and medical illustrations and influenced by Max Ernst, turn-of-the-century psychiatry and psychoanalysis, and Georges Méliès.

With his mural at Jimbo’s Bop City in 1950

With his mural at Jimbo’s Bop City in 1950

Avant-garde film scholar P. Adams Sitney has written extensively on Smith’s Film #12 Heaven and Earth Magic, and on the topic of alchemy in Smith’s film opus he has said, “The chance variations on the basic imagistic vocabulary of the film provide yet another metaphor between his film and the Great Work of the alchemists. For the Renaissance alchemist, the preparation of his tools and of himself equaled in importance the act of transformation itself. Since every element in an alchemical change had to be perfect, each instrument and chemical had its own intricate preparation. The commitment to preliminaries is so strong that in its spiritual interpretation, alchemy becomes the slow perfection of the alchemist; the accent shifts from goals to processes.”

For all the intricate codifying that went into Smith’s collections and artwork, a parallel and destructive urge ran through him. Toward the end of his life, Smith taught for several years as a shaman in residence at the Naropa Institute in Colorado, and a former student said of his process there: “He would just concentrate and study and work and go haywire, drive himself crazy, getting everything in exactly the right order and then he would just give it a kick and say ‘that’s it.’ But he knew when he kicked it that he’d chosen the right moment and however it fell was going to be right.” This Surrealist technique allowed for the magic of alchemy to occur — the purification process of arranging film pieces perfectly and the final “act of God” that transformed the base work into a noble one.

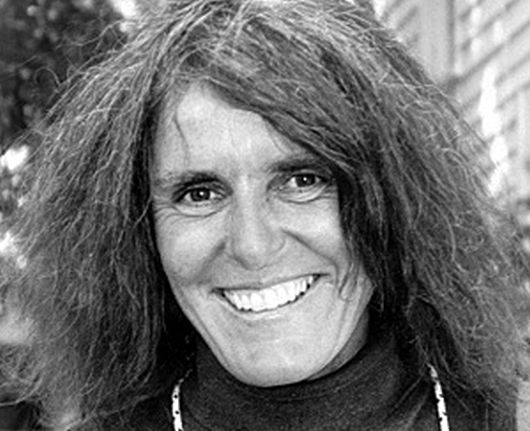

in 1965

in 1965

When Smith’s violent gestures were taken to the extreme, however, they resembled self-sabotage. Heaven and Earth Magic was printed in black and white, but Smith built a special projection unit for showing it that allowed for him to change its color and shape using a series of filters and gels. Smith threw the projector out a third-story window in a tantrum, destroying it. And during a talk at the Queens Museum in 1978, Smith would say that the filmstrip of Heaven and Earth Magic screened that day was a fifth generation print, the previous four having been thrown out by Smith and later recovered by friends.

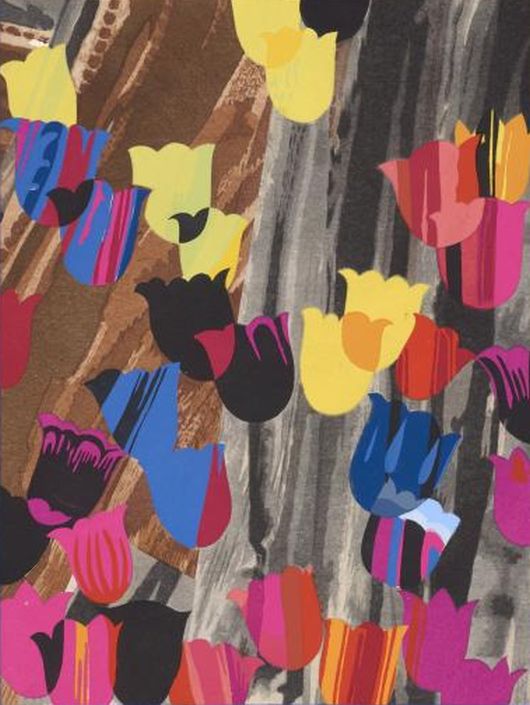

Still from Early Abstractions, 1941-1957

Still from Early Abstractions, 1941-1957

He was equally destructive with himself and his relationships. He liked to brag about killing people and claimed to have never had sex (the latter claim another of the few likely true statements about himself). “Smith is a legitimate visionary, whose disdain for the personality can be found not only in the absence of biographical references in his art but also in the lies he tells about himself, in the tricks he plays so assiduously to hold others at a distance, and in his utter disregard for physical and emotional well-being, whether his own or that of others,” wrote poetry scholar Stephen Fredman. He would borrow equipment from friends and then refuse to return it or pawn it for money without apology. Another anecdote about Smith has him reading to his mother on her deathbed a chapter titled “Sadistic Trends” from Karen Horney’s Our Inner Conflicts. No word as to whether Smith was accusing his mother, in her final days, of being a sadist, or if he was trying to offer an explanation for his behavior.

Hunchbacked from childhood rickets, Smith further deteriorated his body with decades of drug and alcohol addiction and poor eating habits. (When he finally adopted a “healthy” diet late in life, it was said to consist of “bee pollen, raw hamburger, ice cream, and Ensure,” as well his usual marijuana and “whatever combination of Sinequan and Valium he found in his jacket pocket.”) Between the six months Smith worked as an engine degreaser operator for Boeing while in college and his final years as a teacher, Smith seems to have survived solely on the occasional grant and benefactor or generosity of friends (particularly Allen Ginsberg, who let Smith room with him on several occasions). His indifferent poverty meant that he had a well developed sense of ingenuity, but it also resulted in many projects remaining unfinished and the loss of his collections. In 1965, while working on a recording project in Oklahoma, Smith was evicted for nonpayment of rent and his irreplaceable artwork and collections were dumped in the Fresh Kills landfill.

With Allen Ginsberg in 1987

With Allen Ginsberg in 1987

In a 1976 interview, Smith said, “When I was younger, I thought that the feelings that went through me were — that I would outgrow them, that the anxiety or panic or whatever it is called would disappear, but you sort of suspect it at 35, [and] when you get to be 50 you definitely know you’re stuck with your neuroses, or whatever you want to classify them as — demons, completed ceremonies, any old damn thing.” It is this rare confession of vulnerability that perhaps gets to the heart of Smith’s alchemical obsessions. The desire to ameliorate these feelings is the desire to achieve spiritual transmutation. And I can’t imagine a more beautiful way to consider one’s uncomfortable feelings and self-defeating urges than as completed ceremonies, timeless and inscrutable, something at home in the nation of the Anthology of American Folk Music. Anarchist Mikhail Bakunin’s quote seems appropriate to consider in conclusion: “Let us therefore trust the eternal Spirit which destroys and annihilates only because it is the unfathomable and eternal source of all life. The passion for destruction is a creative passion, too!”

Helen Schumacher is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Brooklyn. She tumbls here and here. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She last wrote in these pages about Joy Williams.

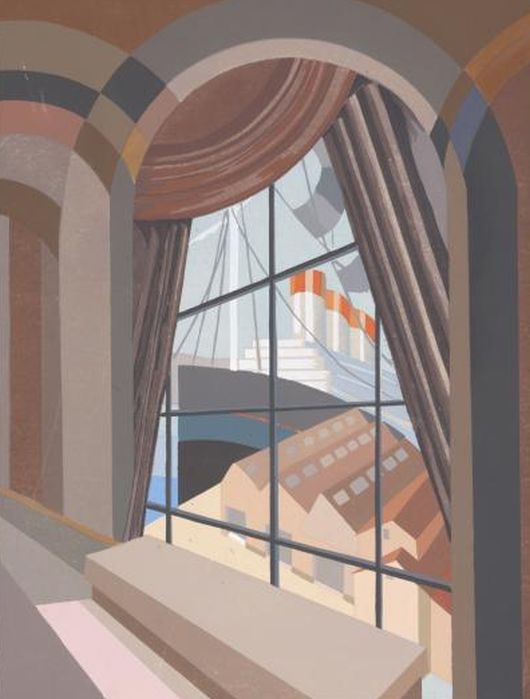

still from the Anthology Film Archives

still from the Anthology Film Archives

"Wagoner's Lad" - Buell Kazee (mp3)

"The Moonshiner" - Buell Kazee (mp3)