BOOKS

BOOKS In Which These Are The Reasons She Was Shunned

Tuesday, May 17, 2016 at 10:49AM

Tuesday, May 17, 2016 at 10:49AM

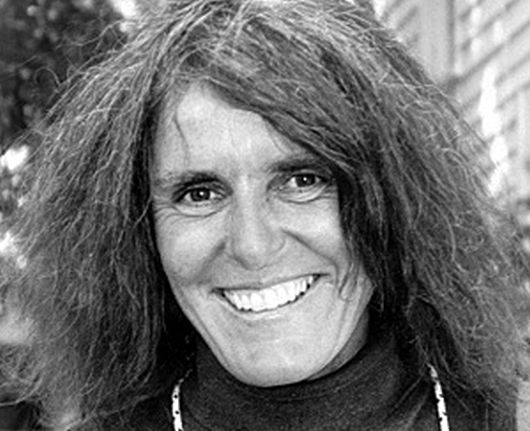

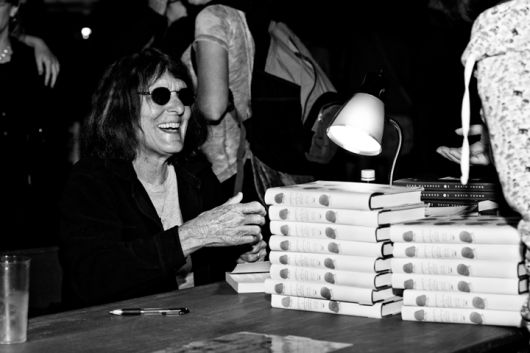

The Oracle

by HELEN SCHUMACHER

But who knows what good might come from the least of us? From the bones of old horses is made the most beautiful Prussian blue.

- Joy Williams, Dimmer

There’s the pelican child. The orphan boy whose eyes ooze a milky substance. The girl named after the genus of crows and ravens, whose friends find her presence nearly as portentous as the birds’. The shallow boy who laughs in a noblesse oblige fashion. Kate who, even as a child, had the glimpse of extrication in her eyes. The stroke victim who dreams of thirst. The cowboy with the blood of lambs caked beneath his nails. Doreen the sorority girl who rubs self-tanner on her nipples. Deke the wino whose tight leather pants suggest no knob. Alice who has been told she gives the concept of carpe diem a bad name. Corinthian Brown who sleeps in the junkyard and has an unpleasant skin condition. The fitful lady in a bookstore ordering a copy of The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets so as to read about Coatlicue, the Aztec “protectress of lone women, of female outsiders who had powerful ideas and were therefore shunned.” God driving a pink Wagoneer. The piano player for hire, sly with a greedy body and wayward mind — in short, a pervert.

These are the characters that populate the work of Joy Williams. They can be cretinous and difficult to look in the eye. “Escapees from some pageant of atrocities” is how one critic described them. However, most aren’t miscreants, just daydreamers with primitive social skills. They love and yearn to be loved, but in a distorted, unbecoming, predaceous, careless way. A Williams character is often an orphan or an alcoholic or both. They spend a lot of time grieving in peculiar ways. They greet the suffering of others with ambivalence or, at best, curiosity. Their grip on reality is tenuous, making action and thought difficult to sort out.

Despite their vulgarities, her characters are endearing. They are more familiar but still comparable to those of the gothic menagerie: Flannery O’Connor’s Enoch Emery, Carson McCullers' jockey who dines on rose petals, Katherine Dunn’s family of geeks. Or Karen Russell. In her review of Russell’s Vampires in the Lemon Grove, Williams could have been talking about herself when she complimented Russell on “the wily freshness of her language and the breezy nastiness of her observations.” Williams has a favorite way of carving out the details of her characters and their mise-en-scène. That is, through simile. She relies on it heavily, especially in her earlier work, but not to a fault. Her skill is such that I welcome each one. A long but not exhaustive list of my favorites:

Freddie Gomkin’s wife, who had a face like an ewe, gave birth to twins in January, when everyone knew that poor Fred had been gelded in the war.

She could hear Tommy’s voice faintly in the air, but it seemed contained, as though in some heart’s chamber.

She touched her tiny ears, which looked as though they’d been grafted on in some long-ago emergency operation by an inappropriate donor.

Miriam had once channeled her considerable imagination into sex, which Jack had long appreciated, but now it spilled everywhere and lay lightly on everything like water on a lake.

The brandy rocked like mud in the paper cups.

The moss feels like Father’s hands, which were always very rough although there wasn’t any reason for their being so.

“Oh remember that my life is wind,” he kept bringing up like yesterday’s breakfast.

Spreading decline like a citrus tree.

Writers are like eremites or anchorites — natural-born eremites or anchorites — who seem puzzled as to why they went up the pole or into the cave in the first place.

The rain was clattering like teeth in a cold mouth.

Gestating is like being witness to a crime. And I am furtive, I must admit.

The words so clear and useless like a mirror hung backward on a wall.

He had straddled the baby as it crept across the ground as though little Mal were a gulch he had no intention of falling into.

She began kissing his neck, sucking up the skin beneath her teeth as though she were chewing on an artichoke.

It is as though she had bones webbed in her throat.

Heartbreak surrounds her, though she seems unaware of it. She moves through it like a leaf, like a feather, like a falling piece of soot. It is as though she is living out some event that is not part of her life.

Everything in the world was slick and trembling like a gland, like something gutted, roped and dangling from a tree.

Words are macerated like bones being cleaned, and new meaning comes from the sentence assembled. Coca-Cola becomes an eccentricity. A palmetto bug becomes a widow’s amulet. A voice’s bitter tenor becomes the pith of a tree.

A practiced objectivity is necessary for Williams to successfully put together these similes where the pure and putrid hold hands. Critics and Williams herself have pointed out that the idea of “seeing things without preconception” often comes up in her writing. Besides aiding in her simile construction, this perspective is also key to how her characters relate to the world. It allows for the people, animals, and objects in her work to all share the same possibility of thought and emotion. To build on one of Williams’ phrases: Her attitude of impartiality allows for her work to navigate the straits between the living and the dead and the unliving and the undead.

This navigation is exemplified in Williams’ short story “Congress.” It begins with adorations for forensic anthropology professor Jack. His life is filled with praises from those who can finally move on now that Jack has reconstructed the last moments of a loved one’s life through hair and bone fragment. The pieces don’t fit together as well at home; while Jack is an expert gardener with prized rose bushes, his girlfriend Miriam has taken to stealing dying plants from supermarkets and lawns with the intention of nursing them back to health in their yard. Her attempts never thrive like Jack’s flowers.

The dynamic changes when Jack is severely disabled in a hunting accident. The accident is described in a slew of similes: “Then late one afternoon when Jack was out in the woods, he fell asleep in his stand and toppled out of a tree, critically wounding himself with his own arrow, which passed through his eye and into his head like a knife thrust into a cantaloupe. A large portion of his brain lost its rosy hue and turned gray as a rodent’s coat ... He emerged from rehab with a face expressionless as a frosted cake.” After the accident, Jack is doted on by the student who introduced him to hunting. The student, Carl, even replaces Miriam in the bedroom.

Now finding herself freed from Jack’s judgments, Miriam develops an affection for a wobbly lamp Jack made from deer hooves. They read together daily. (At one point, they argue over a book of verses. Amusingly the lamp finds it repellent that the verses confuse thought with existence.) And when Carl decides Jack needs a road trip through the Southwest, Miriam insists they also bring the lamp. In the end, Miriam and the lamp stay behind at one of the desert towns, home to a taxidermy museum, where she is asked by the taxidermist-in-residence to take over his duties of answering questions posed by tourists who come from all over seeking an oracle.

It’s a story brimming with Williams' favorite subjects — taxidermy, the desert, misfits, mortality — and in it the corpus has as much to say as the living; the people can be as impassive as the landscape. With prickly humor, she explores the desire for purpose, for meaning in life and death. That Williams doesn’t elaborate on motivations gives the story its poignancy.

In the early ‘80s, Joy Williams was sometimes lumped with the “Kmart Realists” — writers like Raymond Carver and Ann Beattie. It’s a descriptor that seems fit for a William Eggleston photograph, but Williams’ work is more analogous to Diane Arbus. It’s a glimpse of the underbelly of ordinary. John Barth called it cool-surfaced fiction. And indeed there is a distantness to Williams’ fiction. She doesn’t coddle our species. Hers is the writing of someone who loves humanity but refuses it authority.

Helen Schumacher is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Brooklyn. She tumbls here and here. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She last wrote in these pages about recess.

"In the Backyard" - Henrietta (mp3)