FILM

FILM In Which We Submit To The Fantasy Of Vertigo

Wednesday, November 14, 2012 at 11:06AM

Wednesday, November 14, 2012 at 11:06AM

In the Realm of the Senses

by SHAHIRAH MAJUMDAR

Vertigo

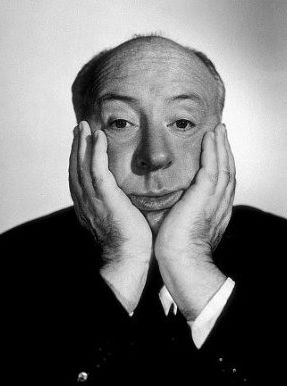

dir. Alfred Hitchcock

128 minutes

Love me for as I am, for myself.

–Judy/Madeleine

We forget that Vertigo is also a love story. Its love narrative is a twisted Calvary road, undermined by death, splintered by betrayal, and a film that twice kills off its female object of desire is perhaps not the most appealing of romantic studies — yet, there are few films that recreate so powerfully what it feels like to fall in love.

Vertigo recently took the top slot at the BFI Sight & Sound poll of greatest films, displacing Citizen Kane. Some would say there are many others better made, including others by Hitchcock, but what is unforgettable about Vertigo is how it resonates with the senses: how it compels through its use of sound and stillness, the human face and figure, story and symbol, light and color and camera movement. As a movie experience, it is hypnotic, disorienting, and works with a logic loosed from linear or rational constraints. Its magic — its sheer gorgeousness — is that its logic is purely that of the cinema: of the senses, of the artifice of attraction.

When you look at the premise that Scottie, Jimmy Stewart’s retired police detective, has been sold, it is terribly wonky. A girl believes she is a ghost. She succumbs to fugue states after which she does not remember what she has done. She wanders San Francisco, driven by memories that could not possibly be hers. Her husband, unnerved by worry, hires Scottie to make a study of her and arrive at a set of foregone but impossible conclusions.

Scottie is a rational man, a man who has made his living through investigative, evidence-based reasoning. He is dry, educated and affable; it seems unlikely that he would be so gullible, so ripe to consume the strange plot spoon-fed to him by Madeleine’s husband. But he swallows the story without skepticism, mouthful by mouthful, until it consumes him. Both consumed and consuming, with childlike wonder and a grown man’s sexual obsessiveness, Scottie opens himself fully and is possessed.

Surely, what madness is this? We believe it is Madeleine who is mad, yet it is Scottie who sinks inexorably into madness as he succumbs to an experience that has been scripted for an audience of one, an experience designed to prick his particular senses and loosen his particular mind. His friend Midge tries to pull him back into the rational world with gentle affection and by pointing out the dissonances in the Carlotta Valdes story with irony and wit, but the task is impossible.

Love — the kind of love born out of irreducible desire, not the kind founded on OK Cupid stats, good conversation and shared history — itself is a kind of madness. What Gavin Elster — who assumes (like the Great Oz) the role of the little man pulling levers behind the curtain and thus becomes a proxy for the director himself — achieves is the willing suspension of Scottie’s rationally functioning self. He is unraveled, undone.

What Vertigo, as a cinematic experience, achieves is similar. Mesmerized by our senses, we submit ourselves wholly to the machinery of the movies: to Bernard Herrmann’s circling score (now lush & moaning, now skied & skittering; always vibrating bones and belly with vertiginous sensation.); to the marble whiteness of Kim Novak’s face (as Judy, she is merely voluptuous; as Madeleine, she is simultaneously voluptuous and yet her face and body cold & hard like marble); to that shallow San Francisco light which filters and obscures through its foggy radiance; to dizzying camera movements that make what is far near and what is near far again; to the revolving door of chromatic schema, textured with rich shadows, smeared colors, symbolic shadings; to a world in which passages ever open upon other passages, a world where the self can never be still…

Vertigo’s signature camera movement — the dolly zoom (zoom forward, track backward) — echoes the movements of love, madness and memory. We hurl forward while simultaneously pulling back. Things are not as they appear. Rooms, chords, pupils, hearts dilate & contract before us… Similarly, this is representative of the way that cinema itself works, of the kind of double vision that is necessary in order to fully possess the movie viewer. A film must seduce — must pull you forward — with all the tricks of lighting, mise-en-scene, make-up, wardrobe, camera movement, etc. At the same time, it must allow the rational mind to stretch and wander, to pull back and observe its own experience with fluid curiosity. Vertigo creates this easy slippage between the conscious and the unconscious, the rational and the sensual, the material and the ineffably ideal. In doing so, its dissonance becomes irreducible: impossible to collapse, to render into the realm of the ordinary.

We love movies because, for a brief moment, they allow us to live in a world in which things are not as they are but as we want them to be. Vertigo achieves this in a double way: not only does the subtle manipulation of cinematic syntax draw us into Scottie’s interior, a lovely but haunted place increasingly dominated by an obscure object, but Scottie becomes a proxy for the way we — as viewers, as lovers, as flawed and fragile human selves pushed by the surging pulse, by the blundering mind — allow ourselves to submit to fantasy. In this hunger for astonishments, Scottie and audience are twinned.

Juxtaposed against Vertigo’s grand themes of love and death and obsession and castration anxiety and the construction of femininity, this theme of how the language of cinema is the same as the language of desire perhaps feels small, unremarkable. Yet it is impossible to talk about movies, particularly Hitchcock’s movies, without talking about the male gaze. There’s been a lot said about the camera’s capacity to render the female as a passive body, blank and willing, ripe for possession by a penetrating gaze. But perhaps, like Scottie, we long to be possessed. Perhaps this desire, this gaze is what also nourishes an immense & myriad self. Perhaps, sometimes, we awaken only by submitting. Perhaps we all, if but for a moment, long to go mad —

Late in the film, after Scottie has endured the tragedy of Madeleine’s demise, survived its traumas, (re)discovered Judy/Madeleine and embarked on the project of remaking Judy in Madeleine’s image, we are given a glimpse into Judy’s interior. We learn that her desire for Scottie is a mirror of his for Madeleine. Despite the reservations of her practical Kansas upbringing, she also forsakes what is “safe” and chooses to submit to a fantasy of what could be versus what reality suggests there is.

Hoping for completion, she asks that Scottie “forget the other and forget the past,” that he “love me for as I am, for myself.” But, if anything, what Vertigo tries to tell us is that loving a thing for what it “is”— this abstracted, Platonic notion — is an order of experience which the self which is obscured to itself fumbles to achieve. How can you love what you do not know? How can you know what you cannot see? Always the senses veil the object, and always the veil reconstitutes the dream.

When Judy, in her final lines, before the fall, says, “I let you change me because I loved you,” she defines how the artifice of attraction becomes the logic of attraction itself. Her artifice is what Scottie loves; her artifice exists because their love does.

I am always bothered by Vertigo’s ending, its achingly fateful final scene. Scottie’s nagging intellect finally discovers the deception, rends the veil and pushes violently back against the betrayal. The motivations and machinations of Judy/Madeleine are laid bare, and we long for an ending in which both see each other for who they are and embark on something—whether alone or together—founded on evidential truths. Instead, there is the scream and the fall and the clamor of bells and the nun. Again, Vertigo eludes rational reconciliation by flooding the senses. What did Judy/Madeleine see? From where the nun? Why the scream? The orchestral strings thicken, the camera tracks backwards, framing Scottie in the hollowed white drum of the Mission… We will never know.

We are left with the not-knowing — and that is where Vertigo locates the heart’s own vertiginous commotion. Movies, madness, love. All so irreducible. Abide these three.

Shahirah Majumdar is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in New York. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She last wrote in these pages about Argo.

"Scene D'Amour" - Bernard Herrmann (mp3)

"The Necklace" - Bernard Herrmann (mp3)

"The Rooftop" - Bernard Herrmann (mp3)

Shahirah Majumdar,

Shahirah Majumdar,  hitchcock,

hitchcock,  vertigo

vertigo