FILM

FILM In Which Ida Lupino Wore A Lot Of Face Paint

Thursday, December 8, 2016 at 11:19AM

Thursday, December 8, 2016 at 11:19AM This is the first in a two part series about the actor and director Ida Lupino.

She Lived By Night

by ALEX CARNEVALE

When Ida Lupino arrived in the U.S. for the first time at the age of fifteen, Paramount representatives greeted her at the dock in Hoboken, New Jersey. She and her mother stayed at the Waldorf Astoria. The next day the picture of the Englsih actress was on the cover of the Los Angeles Times. "By the time we landed," she wrote her father, who was staying behind in England, "we looked like a couple of dead seagulls."

Paramount told her they felt she could be the next Jean Harlow, who was a platinum blonde whereas Ida was a brunette. She was nonplussed, and it was not long before she was making her dissatisfaction known. "I cannot tolerate fools, won't have anything to do with them," she told the press. "I only want to associate with brilliant people."

Before she ever debuted in a starring role, Ida Lupino contracted polio. Her feet were so painful she could barely stand. She thought of killing herself. As she recovered, she returned to the set long before doctors thought she would. That year she made $23,400.

with howard hughes

with howard hughes

By 1935, Lupino already had a reputation as a handful. Some directors were scared away by her outspoken nature. "'I'm mad,' they say. I am temperamental and dizzy and disagreeable.," she told the press. "I can take it. Only one person can hurt me. Her name is Ida Lupino."

Her first Hollywood boyfriend was a British stage performer named Louis Hayward. Unlike the Jewish performers who took on stage names to conceal their ethnicity, Hayward's real name was Seafield Grant. This lothario was nine years older than Ida, and had to compete with a variety of men who Ida found uninteresting, including Howard Hughes. Hayward hated when Ida wore makeup, calling it face paint.

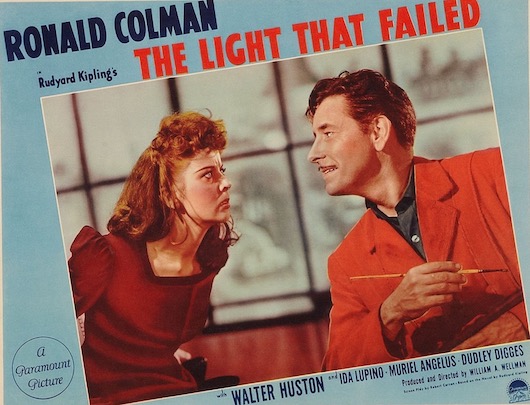

with first husband Louis Hayward

with first husband Louis Hayward

At eighteen Lupino was loaned to RKO for a series of films which did nothing but stall her career. She rented a house above the Hollywood Bowl. Returning her hair to her natural color, she decided to leave Paramount. England had no interest in her return, so she fired her agent and married Louis Hayward in the Santa Barbara courthouse. The couple moved to Beverly Hills with their terrier. After a two picture stint with Columbia, Ida demanded from mercurial director William Wellman what would become her breakout role: the slut in an adaptation of Kipling's The Light That Failed.

She signed with Warner, where she starred opposite the tiny, not-yet-a-star Humphrey Bogart in They Drive by Night. In her biggest roles, Ida played crazy with a certain contained zeal. It was not something that was done well very often, and it distinguished her from an entire generation of actresses. Her next film with Bogart inspired the jealousy of Humphrey's wife Mayo Methot. She made more than Bogart on the film High Sierra: 12,000 a week.

Ida was now a star, and this upset her husband Louis tremendously. He began complaints to her when they woke in the morning, and she pretended to go along with it, explaining to the media that "the man is the master of the house." Louis kept her away from parties; their usual entertainment was recording the conversations of friends during dinner and playing it back afterwards.

Her closest friends had always been men, with whom she felt she did not have to be competitive. Joan Fontaine and Ann Sheridan became her closest actress pals. "Ida Lupino," Fontaine wrote of her during this period, "is the nearest thing to a caged tiger I ever saw outside a zoo. I don't think she has ever been still a whole minute of her life." Absolutely never bored, Ida was most alive in the evenings, when her mind roamed endlessly.

with Humphrey in "High Sierra"

with Humphrey in "High Sierra"

After her father died of cancer, Ida reevaluated her career. A disastrously boring film where she played Emily Bronte was shelved for years before being recut and released to little fanfare. She feared being typecast as a crazy woman, and an idea popped into her head as a way of avoiding the fate Warner had consigned her to: she would be a director.

During the war, Ida visited returning serviceman. Louis Hayward, now a captain in the Marines, was deployed in Japan, where a bullet cracked his helmet. He went into combat carrying a camera purchased for him by his wife. When he returned home, he was intensely traumatized. Hayward was treated at three different hospitals for depression, but none shook his basic conclusion: He was done with Ida Lupino.

Ida went from a nervous breakdown to a new, Casanova-esque boyfriend in just over a year. The Austrian Helmut Dantine was a violent, drunken sociopath who could be charming when he was slightly sober. (Louis Hayward remarried in May of 1946.)

Newly single, Lupino focused on her writing. William Threely was her pen name, and she sold a screenplay she wrote with her friend Barbara Reed to RKO for $3,000. Warner demanded Lupino sign an exclusive contract – her previous deal allowed outside work, an extremely unique arrangement in the industry. When Lupino refused the new terms, she was on her own completely at 29 years old.

Like her last husband, Collier Young was ten years older than Ida. Unlike Hayward and Dantine, he was not an actor but a frustrated Hollywood writer. He was not her first American man, but he was the first one she married, at the Presbyterian Church in La Jolla. "One of the exciting things about Ida," Collier explained to the press, "is her unpredictability."

Even as she continued writing, directing was foremost on Lupino's mind. Many women had been successful screenwriters before Lupino, and a few had even stepped behind the camera. None had ever done with Lupino's ability. In 1945 she met Roberto Rossellini, who told her that "In Hollywood movies the star is going crazy, or drinks too much, or wants to kill his wife. When are you going to make pictures about ordinary people in ordinary situations?"

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording.