ARCHITECTURE

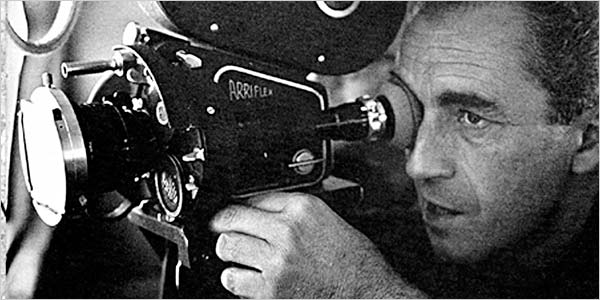

ARCHITECTURE In Which We Listen To The Reminiscences of Julius Schulman

Thursday, July 16, 2009 at 11:50PM

Thursday, July 16, 2009 at 11:50PM

God's Great Plan

by JULIUS SCHULMAN

The architectural photographer died at the age of 98 yesterday. He recorded these reminscences in 1990.

I was born in Brooklyn, New York on October 10th, 1910 with two sisters and one brother. And my mother and father had come from Russia, separately, at the latter part of the last century. The family moved to Connecticut when I was a few months old.

My father was a farmer in Central Village, which is northeast of Norwich, which is in turn about twenty miles up the Thames River from New London, Connecticut. That's on the way up towards the Rhode Island/Massachusetts border. We had a large farm, I don't remember how large, one hundred acres or so. Apparently we lived off the farm, which was a mile and a half outside of Central Village. My two sisters, brother, and I walked to school every day. I was then five years old.

What I remember in my deepest memory is strange, because here I was sitting next to my mother on an open wagon. She drove the horse. My father with other members of the family, the brothers and sisters, on another wagon in front of us, leading the way. We apparently had been riding the horses and wagons from our previous farms, where we had lived for a short time. I remember my father waving to my mother towards what appeared to be a house up on a slight rise in the land above the roadway — dirt road of course. He turned with his horse and wagon up the drive to the farmhouse where we were to live the next three or four years. That was the beginning of my memory of our approach to the farm and the ensuing experiences.

My mother and father worked the farm with one helper. We lived off of it. There was an occasional buggy trip to Moosup for fresh meats, chicken, and fish — a distance of three miles.

Of course, as children, we failed to realize how gigantic a task was performed by our mother. I have a profound respect for her. As with the women of the covered wagon days, walking mostly across deserts and prairies, snow-covered mountain passes, and constantly in fear of Indian attacks were daily events.

At least my mother was capable of raising five children. The youngest was born at home shortly after we arrived in Central Village. Up at dawn to care for the scores of chickens, collect eggs, milk the cows, and then to prepare breakfast for a family of seven! Yet there was the ability to bake breads. Between those chores she cut potato "eyes" to prepare the planting with my father, whose horse-drawn plow furrowed the soil.

In those days, California was magic. It was the land of gold, and you heard stories from people. My father apparently knew people who had heard about--from their friends or relatives--about California. It was a land of opportunity. It was a land of endless possibilities, physically, climate, and economically — which of course turned out to be true, because we came here in September of 1920 by train — mother, father, five children. And you think of the covered wagon days, this was deluxe because you traveled by train, stopped in New York for a couple days--my mother and father had brothers and sisters there — then we took the train and went on to California. Traveling with five children cross-country I guess is no picnic even by train.

My brothers and sisters and I went to the elementary school here, at Alpine Street School, near Sunset Boulevard and Figueroa Street. My father's store was on Temple Street a few blocks away. It was difficult for me to understand how my father did accumulate enough wherewithal to make the drastic moves in the family's life. He did have one other occupation when we lived in Central Village. He was gone for a long time certain parts of the year, and it turns out that he had connections with fur trappers in northern New England and into the Canadian New Brunswick province.

What happened in my photography experience began briefly in 1927, when I was in the eleventh grade in high school. We had a choice of a course in art appreciation for a semester or, then, what was one of the first photography classes in the United States. In high school, we were given the opportunity to have a course in photography.

Everyone had Kodak box cameras. It wasn't called a Kodak; it was just called "Eastman Box Camera." And so for the class we had assignments to take pictures around... We were near Hollenbeck Park, which is a few blocks away from Roosevelt High School. We used to go there for assignments and take pictures of the lake area and a beautiful old wooden bridge. I did well with the box camera, and found that I was able to take care of the assignments and got very good training in how to develop roll film in the darkroom and make prints. Then one of the assignments, which was very important, to photograph events at the southern California high school final track meet at the Coliseum.

This was in May 1927, and the assignment from the teacher was to take a picture of a track meet action. He warned us, "You can't photograph action with your Brownie box cameras. If any of you have a chance to get or borrow a news type of camera, which has higher speeds to stop the action of sports, try to get that, because you can't do much with a Brownie." So anyhow, I went to the track meet, and found I was able to get a location where the high hurdle races were being set up, up and above the tunnel where the track meet still is run from today. The hurdle races start from under the tunnel and run out over the hurdles towards the east end of the coliseum. And I set the camera there, after observing the attendants setting up the hurdles for the race. I said to myself, "Gee, that looks good in the viewer of the camera." When the race started I took a picture as the hurdlers came over the first hurdle.

I didn't have anything to do with photography, after 1927 or '28 when I went to the university. Or when I went hiking and camping I didn't think of taking pictures in those days — until 1932 or '33 when I began to take pictures with my Vest Pocket camera. I still have many of those pictures. Some were printed in the above issue on the Angeles Magazine.

Then '34 to '36 I was up in Berkeley for two years. 'Cause a friend of mine was getting his master's degree and he knew I was bumming around at UCLA after two weeks in their engineering class where I was enrolled. You see, I was a ham radio operator in the twenties, from 1926. I was interested in electrical-technical things, so I thought, well, at UCLA I'd enroll in electrical engineering, which was the closest thing... Of course at that time electronics hadn't been "discovered."

No one knew anything about the technique of refined electronic work of any kind. We had electrical engineers, period! And some semblance of interest in radio. So after two weeks at UCLA in the engineering school, I dropped out. Then the ensuing years I wandered around UCLA, auditing courses. I wasn't enrolled for a major because I didn't know what I wanted to be.

So after those years, my friend said, "Look, you're not doing anything. Why don't you come up to Berkeley with me and get an apartment. You can live off the land as easily there as you do here." It turned out that I did go to Berkeley and started taking pictures of buildings around the campus.

Architecture didn't mean anything to me. And yet the strange thing is that — and this was apparently exposed in my first pictures on the campus, at Berkeley — they were good pictures. I was able to identify with composition. And my compositions of my landscape pictures, prior to going to Berkeley, my early landscapes... I have one which was shown on an NBC program. They had a series of programs interviewing photographers not too long ago. And in that period of time, I brought down a group of my photographs to the studio, NBC, and we laid them all out on a large table, and I was interviewed, and the commentator... What's his name? He was the man in charge, the host on the Groucho Marx show. I always forget his name, but it's not important now. But he picked up a picture from the group lying there, and it was a landscape I had done in 1933 or '34 in Berkeley of a windswept tree up on the hills, up in the hills of the little town of Lafayette, which is on the back side of Berkeley. And he pointed to that landscape, that tree picture, and said, "Photographers don't like to show their old work because they feel they can always do better in later years. Now here's a photograph..." He turned it over, and it said 1933, Lafayette, California, and so on. He asked me how I felt about this picture. "If you went back there today, could you do it better, since this was taken apparently with your Vest Pocket Kodak?" And I exclaimed, loudly I remember, I said, "Oh, no! This is a magnificent photograph!"

Let’s learn how to take pictures without a camera. And let’s learn to identify - whatever we’re photographing, whether it’s a landscape or a building or an interior - let’s look first and see how we identify ourselves with the object.

What you can achieve if you departed from the hard, militaristic discipline which the architects tried to force on you. The only condition I placed on Soriano in our house here, in the initial design period between '47 and '49, was that wherever we had a sliding door in our house, we would open it out to a screen porch, a screen terrace — which he didn't quite fight, although he resisted, but he knew I meant it. Now our screen areas, which we have off our living, dining, and bedroom areas, really make the house as evidenced by the reaction of other people — architects, and editors, and publishers and architectural historians. They see this house; they see how it works.

I did this many times, like in this 1947 photograph of the Neutra Kaufman House in Palm Springs, which is standing here. It's a twilight picture, which is a 45-minute exposure. I had been doing photographs with Neutra at the house, and towards evening, as the sun was setting, I noticed, looking out to the eastern desert, there was a beautiful glow in the sky, and I said to Mr. Neutra, "Just a moment. I want to go outside and look at the house from the eastern side of the property." I looked at the house and I thought, "My God! Look at the twilight developing, and look at the mountains, and the scene which was being created by the changing light!" So I quickly ran into the house, against the will of Neutra, because Neutra was insistent that we continue working, because he wanted to do more interiors in the house.

So I said, "No, Richard, we can't do that. That sky is beautiful, the mountains are beautiful, and the light glowing inside, the exposure values are just right." So I ran out with my camera and my film bag, and I set up the camera, and out of this came this photograph. And I had a shutter which didn't have to be cocked. You can open and close this shutter at will, expose two or three seconds at a time, and then run into the house and turn on lights, turn off lights, and built, kept, like building blocks, kept building my exposure for this scene. And out of this came this photograph. Now the point I'm making is I didn't know what I was doing.

My pictures were very natural. There's one there on the table of a house overlooking the ocean at Laguna Beach. I took that for a builder. It was designed by a well-known architect at the time. But the balance between the interiors and exteriors was so perfect that you felt that you were actually in the room. The eye would adjust when you were in the room, from the light inside to the light outside. But photography-wise it doesn't work that way. You have to learn to see and feel the proper exposure for the outdoors--the ocean in this case, the bay with the glistening, reflecting light on the surf — and then you also have to say, "Now let's see, how can we produce lighting on the interior to give you a feeling of natural light in the house, as the eye would see it, but then without being evident that a photographer had produced this scene with all kind of conflicting lights and shadows?" My balance of photography lighting was such that this is what prompted many, many people to call on me, because we had mastered the use of lighting, flash, to balance. And even to this day, I marvel at some of the pictures we used to take, because they were literally masterpieces at producing the image of design, interiors as well as exteriors.

Now a strange thing occurred, too, at that period of time, representative of the fifties and sixties, even into the seventies. Many photographers didn't quite know how to use light and flash, and if they came into a house which had a lot of windows, they would (a) draw the draperies, or (b) photograph at nighttime, and still leave the draperies closed. They weren't getting any ambient light — like the natural light on the ceiling flooding into a room like this where you had a lot of daylight coming in. There's a feeling of soft light.

Julius Schulman died yesterday. You can read more about him here.

"Tired of Sex" - Weezer (mp3)

"Oh No This Is Not For Me" - Weezer (mp3)

"I Just Threw Out The Love of My Dreams" - Weezer (mp3)

Most of the album was written and recorded solely by Rivers Cuomo on 8-track at his home in Connecticut in 1994. In the words of Rivers, taken from an interview in the November 15, 2007 issue of Rolling Stone, "There's this crew - three guys and two girls and a mechanoid - that are on this mission in space to rescue somebody, or something. The whole thing was really an analogy for taking off, going out on the road and up the charts with a rock band, which is what was happening to me at the time I was writing this and feeling like I was lost in space."

Over the course of writing the album, Rivers, who'd enrolled at Harvard in the fall of 1995, changed his focus from the space rock opera theme of SFTBH to the Madama Butterfly theme of Pinkerton.

"Dude, We're Finally Landing" - Weezer (mp3)

"You Won't Get With Me Tonight" - Weezer (mp3)

"Superfriend" - Weezer (mp3)

interview,

interview,  julius schulman

julius schulman