BOOKS

BOOKS In Which You Have No Idea What They've Endured

Tuesday, November 16, 2010 at 11:52AM

Tuesday, November 16, 2010 at 11:52AM

Tell Me How Long James Baldwin's Been Gone

by ALEX CARNEVALE

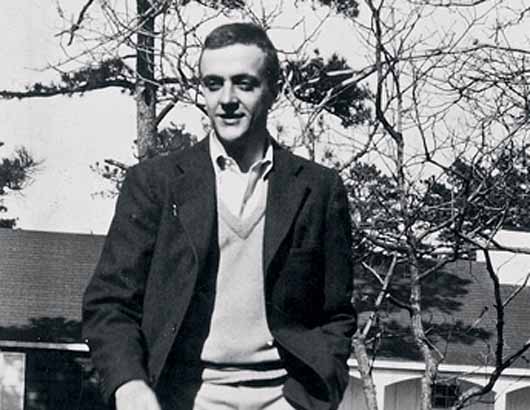

Before James Baldwin made his first ever trip to the American south in 1957, the Harlem-bred prodigy flew to Washington D.C. to talk to the poet Sterling A. Brown. Where Baldwin's work continues to be read in schools and to a certain extent by the general public, Brown's distinguished career is relatively anonymous outside of appreciators of the master poet.

Before reporting on the civil rights conflict for Partisan Review in an article that would be called "Nobody Knows My Name," Baldwin got a rough guide from his mentor on what to expect in his first destination, Charlotte, North Carolina. Brown reminded Baldwin that blacks in the South might resent or fear him, and in David Leeming's biography of Baldwin, he quotes Brown as telling Baldwin "to remember that Southern Negroes had endured things I could not imagine."

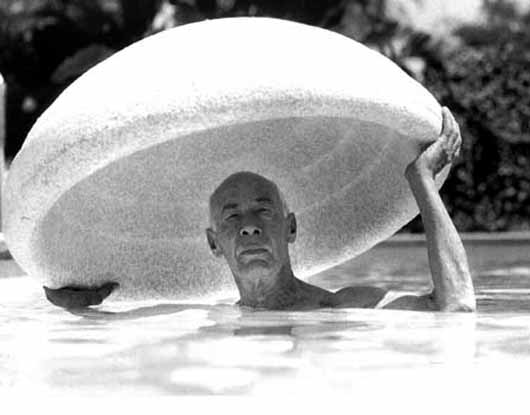

cooking in 1966 in istanbul

cooking in 1966 in istanbul

It is strange to think of Baldwin alive in the world today, walking around in the world he made instead of the one in which he was made. Born in August of 1924, Baldwin's early life in Harlem would later be chronicled in one of the great first novels ever written, Go Tell It On The Mountain. The ostensible subject was Baldwin's domineering reverend stepfather, but the book was to a greater extent Baldwin's declaration of himself as the ultimate outsider.

Initially titled Crying Holy, Mountain established Baldwin's reputation as an emerging talent in world literature. Written in Paris during the first of Baldwin's exiles, the book is almost incomprehensible to young people today, and it was only assigned reading in my ninth grade class because by the grace of God my English teacher never shaved her armpits and told me that referring to Macbeth as being "whipped" was both sexist and inappropriate. Baldwin himself was quickly identified as a gifted student, and he attended high school at De Witt, the legendary Bronx school, after a recommendation by early mentor Countee Cullen.

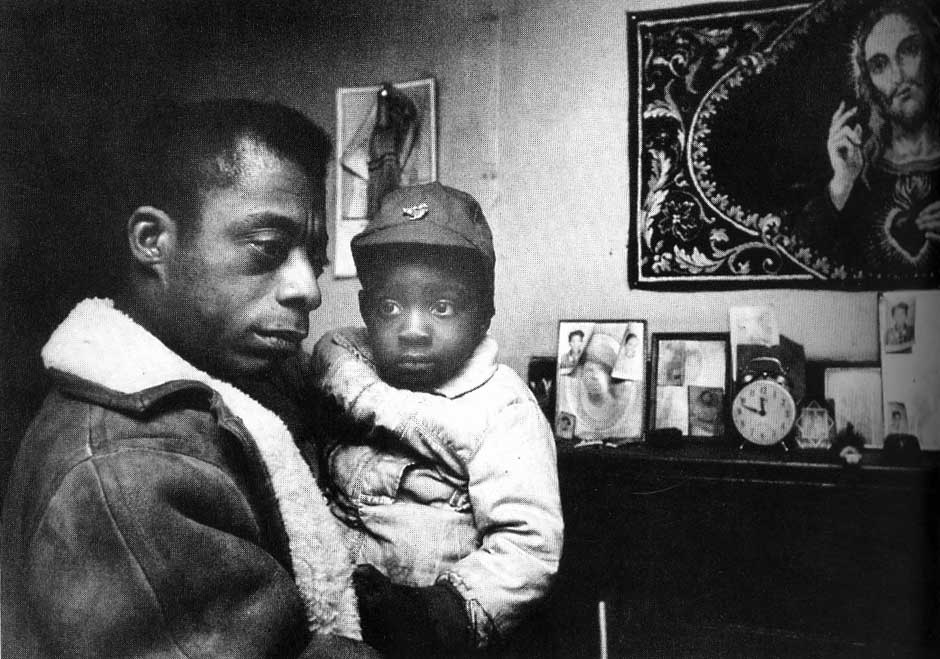

with engin cezzar in istanbul 1965

with engin cezzar in istanbul 1965

At De Witt, Baldwin's classmates included the likes of Richard Avedon, Sol Stein, and Emile Capouya. Still living in Harlem with his family, Baldwin developed a second community, mostly composed of Jews, where he felt at home. This was a crucial step for the young writer, who was for the first time investigating his sexuality. Although he was very gay, Baldwin had relationships with women throughout his life, the vast majority of which consisting of mothering and unwavering financial support.

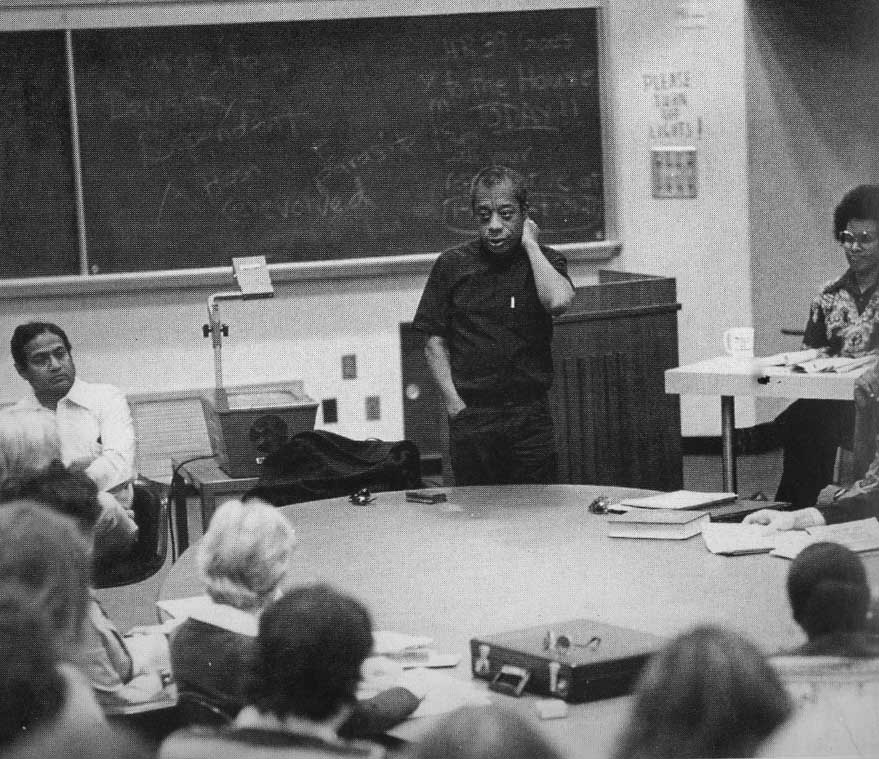

with biographer David Leeming (glasses) and othersBecause of his fearsome stepfather, though, the men in Baldwin's young life loomed large. His friends were numerous and bold-faced: Marlon Brando once paid Baldwin's way back to American after an aborted attempt to go stay in Tangiers with Paul Bowles. His connections with the major names in black literature were more fractured. He would resolve to work harder than his predecessors on relationships with the next generation of writers. As Toni Morrison once put it in a remembrance of her friend:

with biographer David Leeming (glasses) and othersBecause of his fearsome stepfather, though, the men in Baldwin's young life loomed large. His friends were numerous and bold-faced: Marlon Brando once paid Baldwin's way back to American after an aborted attempt to go stay in Tangiers with Paul Bowles. His connections with the major names in black literature were more fractured. He would resolve to work harder than his predecessors on relationships with the next generation of writers. As Toni Morrison once put it in a remembrance of her friend:

I suppose that is why I was always a bit better behaved around you, smarter, more capable, wanting to be worth the love you lavished, and wanting to be steady enough to witness the pain you had witnessed and were tough enough to bear while it broke your heart, wanting to be generous enough to join your smile with one of my own, and reckless enough to jump on in that laugh you laughed. Because our joy and our laughter were not only all right, they were necessary.

By the time Baldwin was ready for the first trip to the south, he had already felt the lax racism of Paris, where many African-American expats went to gather, including Baldwin's major nemesis/foreunner, the novelist Richard Wright. Baldwin's third piece in the fledgling journal Commentary was an attack on Wright called "Everybody's Protest Novel." The two argued about writing for the expediency of a political cause, and Baldwin ended up feeling uncomfortable under Wright's gaze.

embracing Lena HorneWhen he had first arrived in Paris sometime after his 24th birthday, his welcoming party had included Wright and Jean Paul-Sartre. Returning there later in life, he saw Paris as an escape from the literary culture, and perhaps more importantly an escape from America, where he could be James instead of standing in for someone's idea of him. Still, he did not always find Paris as welcoming as he had hoped, although he once said that at the time, he never intended to return to America.

embracing Lena HorneWhen he had first arrived in Paris sometime after his 24th birthday, his welcoming party had included Wright and Jean Paul-Sartre. Returning there later in life, he saw Paris as an escape from the literary culture, and perhaps more importantly an escape from America, where he could be James instead of standing in for someone's idea of him. Still, he did not always find Paris as welcoming as he had hoped, although he once said that at the time, he never intended to return to America.

The publication of two of his essays on the subject of race, collected in The Fire Next Time, thrust Baldwin into a very public position while he toured the country. These broadsides had run in consecutive issues of The New Yorker, and Baldwin appeared on the cover of Time in 1963.

The publication of two of his essays on the subject of race, collected in The Fire Next Time, thrust Baldwin into a very public position while he toured the country. These broadsides had run in consecutive issues of The New Yorker, and Baldwin appeared on the cover of Time in 1963.

In one sense, this represented a kind of progress, a shifting of the debate. It was also a double-edged sword, as Baldwin deftly noted in the introduction to his collected essays:

But it is part of the business of the writer — as I see it — to examine attitudes, to go beneath the surface, to tap the source. From this point of view the Negro problem is nearly inaccessible. It is not only written about so widely; it is written about so badly. It is quite possible to say that the price a Negro pays for becoming articulate is to find himself, at length, with nothing to be articulate about. ("You taught me language," says Caliban to Prospero, "and my profit on't is I know how to curse.") ... Nevertheless, social affairs are not generally speaking the writer's prime concern, whether they ought to be or not; it is absolutely necessary that he establish between himself and these affairs a distance which will allow, at least, for clarity, so that before he can look forward in any meaningful sense, he must first be allowed to take a long look back. In the context of the Negro problem neither whites nor blacks, for excellent reasons of their own, have the faintest desire to look back; but I think that the past is all that makes the present coherent, and further, that the past will remain horrible for exactly as long as we refuse to assess it honestly.

Baldwin was the man of his family now, the world traveler. He feuded with William Faulkner over Faulkner's declaration that he would fight in the street with his racist friends if it came to it. Faulkner's advice to the civil rights movement was to "go slow." Baldwin responded in his essay "Faulkner and Desegregation" by quoting Thurgood Marshall's comment that "They don't mean 'go slow.' They mean 'don't go.'"

This is a world we cannot recognize, and Baldwin actually had to answer for why he wanted equal rights so badly! He concluded his appraisal of the Mississippian by writing "There is never a time in the future when we will work out our salvation. The challenge is in the moment, the time is always now."

James Baldwin, Joan Baez, and James Forman (left to right) enter Montgomery, Alabama on the Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights, 1965.He did so, obligingly, definitively, eventually impatiently. He rememberd Sterling Brown's advice, and his work about race was usually addressed to whites, aiming to convince them delicately, forcing them to convince themselves, really. For his style and manner he was sometimes reproached by his peers, including Malcolm X, who represented at least something of the religious officiousness that Baldwin had rejected in his youth. All that time he told us how difficult it was to want be a part of something he was convinced with absolute certainty could never be.

James Baldwin, Joan Baez, and James Forman (left to right) enter Montgomery, Alabama on the Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights, 1965.He did so, obligingly, definitively, eventually impatiently. He rememberd Sterling Brown's advice, and his work about race was usually addressed to whites, aiming to convince them delicately, forcing them to convince themselves, really. For his style and manner he was sometimes reproached by his peers, including Malcolm X, who represented at least something of the religious officiousness that Baldwin had rejected in his youth. All that time he told us how difficult it was to want be a part of something he was convinced with absolute certainty could never be.

Faulkner refused an invitation to the White House that would have put him and Baldwin in the same room. He was of an ilk of white man whose objection to other people's objections was that they made it all about race. This is not to say something about Faulkner, but ourselves. Even now, when someone argues that an issue has eclipsed race, we can hear Faulkner's words to American blacks in theirs, and know it for a lie.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. He is a writer living in Manhattan. He last wrote in these pages on the letters of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. He tumbls here and twitters here.

with the painter beauford delaney"Peepsie" - Dntel (mp3)

with the painter beauford delaney"Peepsie" - Dntel (mp3)

"Flares" - Dntel (mp3)

"Soft Alarm" - Dntel (mp3)