BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Explore The Archives Of David Foster Wallace

Monday, April 4, 2011 at 9:40AM

Monday, April 4, 2011 at 9:40AM

Holy Text

by JESSE KLEIN

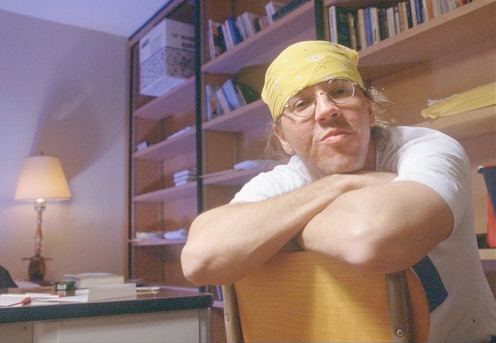

In March 2010, the University of Texas at Austin and the Harry Ransom Center acquired David Foster Wallace’s archives and later that year made them publicly available. Since then, professors, PhD students and journalists have come from around the world to sit with Wallace’s collected, unpublished writings. Since his suicide in September 2008, he has become something larger than he was in life, not just a seminal 20th century writer, a descendent of Pynchon and DeLillo. He has become a cultural, and, cult, figure of mythic status, a Kurt Cobain or Hunter Thompson. For someone who taught so many how to live, Wallace’s decision not to was and is met with confusion, debate, and sorrow.

Archives provide a fan with the opportunity to spend time with the author, with their private thoughts, with what they chose not to share. It gives the reader the chance to look at the raw data without a filter, the biographer. To sift through his archives, something I undertook over a weeklong span, is to celebrate the intentional fallacy, not to draw lines from work to person and back to work, but to better understand the person who created the work, out of curiosity and love for someone who put together strings of words, and webs from those strings, that mean so much to so many people, including myself.

Archives provide a fan with the opportunity to spend time with the author, with their private thoughts, with what they chose not to share. It gives the reader the chance to look at the raw data without a filter, the biographer. To sift through his archives, something I undertook over a weeklong span, is to celebrate the intentional fallacy, not to draw lines from work to person and back to work, but to better understand the person who created the work, out of curiosity and love for someone who put together strings of words, and webs from those strings, that mean so much to so many people, including myself.

There are thirty-four densely packed boxes. The Harry Ransom Center along with Wallace’s widow Karen Green and his family have kept everything: travel documents, college homework, early drafts of articles, essays, short stories and novels, drawings and poems from childhood. The idea was less to read everything, to engulf every snippet of information but more so to gain insight into who he was, why he was, until he stopped being. Suicide is a mode of death inherently linked to a person’s life, and in his writing, as well as his archives, it is ever-present.

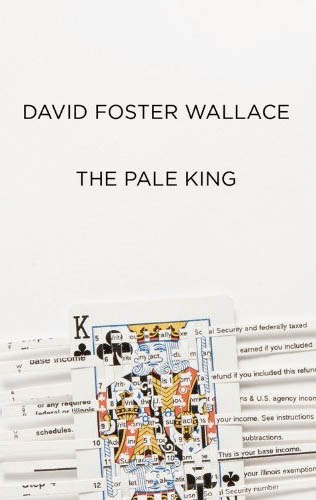

BOX 26 is devoted to Wallace's posthumous novel, The Pale King, set for release this April. The box is made up of dozens, and dozens, of pages of handwritten prose, a handwriting that is not cursive nor print, that takes up one fifth of a line carefully lining the bottom, that leans slightly to the right, or, forward. The first section in the box is called "Fierce Infant", written in the 1st person, in a green, roller ball pen. At the top of the first page, written in caps is the word "FREEWRITING" and next to it an arrow pointing to "potential title for piece." Though, only two pages later, two brilliant pages later, the words "freewriting – means nothing" are written next to "dead prose" which are entombed in a box in the upper right hand corner. These self-denigrating quips are one of the few consistencies from a person with such varied interests, talents. He let himself go on for three more pages only to write "now what" at the end. It did not seem like he gave himself the space to write freely.

It’s been said that The Pale King will be about boredom and taxes. From 1998 onward, Wallace took undergraduate Accounting courses while teaching undergraduate English courses. In his notebooks for these Accounting classes, notebooks that were at once pristinely kept and littered with scattered thoughts, were questions like, "What is 'bypass trust'?" and "explain 'forensic accountant' – tracks money laundering". In BOX 26, there were three chockfull folders of accounting related documents i.e. his homework. On one loose sheet he wrote, "David Wallace (Patty – can I just see how I did? I won't normally ask you to grade me J)." He got 10/10 on the quiz. But you could see through this work that Wallace was not, and likely will not in his book, merely discuss the minutiae of the IRS, the aching tedium it entails. In one correspondence to an academic, he wondered,

Does the IRS or Treasury Dept. have any studies of just how much noncompliance the US Tax System could withstand? That is, have they done any studies of just how many taxpayers would have to refuse to pay before (a) there would be too many to prosecute, and (b) the government would be hurt by lack of income. (a kind of tipping point in other words.)

Wallace is getting at the human condition at its most primal, money/survival, albeit in an oblique, Kafkaesque way. He later asked, "what did hospitals have before ICU’s?" In asking so many questions he finally had to explain, "I have a vague, hard-to-explain interest in accounting and tax policy (utterly divorced from my own taxes, which I pay promptly and fully like an eagle scout)." Stephen Lacy, a CFO, enjoyed the correspondence, understood Wallace's aims, and so in turn offered this as the "most difficult sentence to understand in tax code":

For purposes of paragraph (3), an organization described in paragraph (2) shall be deemed to include an organization described in section 501(c)(4), (5), or (6) which would be described in paragraph (2) if it were an organization described in section 501(c)(3).

It's fun to imagine what Wallace might have done with this dizzying code. Statements like these are impossibly dense but through his translation, they become totally clear. This was one of Wallace’s gifts: he would discuss infinity, or fatalism, or the footnotes of footnotes of tax laws, but would do so with language that was plain, inviting. His use of "like" as written stutter, or of "stuff" in place of the appropriate noun, made Wallace an approachable giant, a Midwesterner, a guy.

(In his review of Siri Hustvedt’s novel The Blindfold, these were his opening remarks: "The point of this review is going to be that The Blindfold is a really good book. The first neat thing about it is that the jacket copy and blurbs are interesting." These statements would have lost marks on a freshman mid-term paper. At times he could be deliberately, though misleadingly, simple.)

Wallace is accessible in part because he’s funny. When he calls Sting "resoundingly unthespian" regarding Dune, that’s funny. When he calls Updike "heartbreakingly naïve" and guilty of a "radical self-absorption" when talking about his novel Toward the End of Time, that’s funny too. And when he wrote his magazine editors, with a conviction and ardor rarely seen from a person so polite, so docile, he’s frightening, and also funny. When Harper's published a section of Brief Interviews With Hideous Men, he had this to say:

DAVE W'S CONDITIONS OF SUBMISSION:

(1) inform auth of Decision to Reject w/in 48 hrs of Decision;

(2) any/all rejected pieces are to be shredded, the shreds placed in a burn bag, then that bag emptied into a high wind at least ten (10) miles from any metropolitan area. we will be watching.

Maybe he was kidding, maybe not. He probably was and he wasn’t. For his Roger Federer article, he said that if they changed more than 100-200 words, he would happily take the "kill fee" and not publish it at all. And, again with Harper's, this time with his Kafka piece, he wrote, "I will find a way to harm you or cause you suffering if you fuck with the mechanics of the piece." Even here, he could not resist a footnote, it reads, "It may take years for the opportunity to arise. I'm very patient. Think of me as a spider with a phenomenal emotional memory. Ask Charis." The “Ask Charis" is chilling, proof that this has happened before. Just ask Charis.

But all this is gravy. All stuff that's preaching to the converted. People know who David Foster Wallace is because he wrote a big, hard, necessary book called Infinite Jest. Based on Wallace’s other writings, his readers know that this is the book he lived to write. All of his passions and preoccupations are there: addiction, tennis, terrorism, TV, prescription drug use, religion, depression. Wallace researched the material that populates the book for years, in a way, was always researching for it.

Wallace was a devoted Alcoholics Anonymous member, and much of Infinite Jest takes place within the sacred circle of AA meetings. Throughout the early 90s, he went to meetings in the Boston area and listened. And took notes. On a page titled "Heard At Meetings", in BOX 15, he transcribed things like, "If you’ve never considered suicide, stay sober for a while", and, "I shit myself every day for years", but also things like, "I see her spending a lot of time laughing", and, "They say it's good for the soul, but I feel nothing inside that you could call a soul." This last quote was recopied into an Infinite Jest notebook in December ’92.

The notebooks from that time, his "siege in the room", were about everything (like Infinite Jest), but from his giving, sad, man-who-knew-too-much vantage point. On high school politics: "the trick for being neither nerd nor quite jock — be no one." On the future of telecommunications: "Audio phone conversations both let you presume the other person was paying complete attention to you and let you not have to pay complete attention to them." Next to this statement is an arrow pointing to "Nixon/Kennedy debates of 1960." His brain was a supercomputer of pop culture. A line is drawn from phony phone conversations to the way television betrayed Nixon’s coolness thirty years before, commenting on Star Trek, predicting Skype.

But the underside, the darkness, everything else he always thought about, was never far, was probably always there. While going through a folder in BOX 15 a loose sheet from a yellow legal pad fell to the floor. It read, "I don’t think it’s an accident that people that shoot themselves shoot themselves in the head." No explanation, just those words in a sea of yellow indifference.

"Good Old Neon", a short story that appears in the 2004 collection Oblivion, is perhaps Wallace’s most deliberate, unadorned conversation with himself. I first read it in a car ride from Montreal to New York on a sunny, summer day. Through the Adirondacks, with my sister on my right and my parents in the front, I was totally destroyed and absolutely electrified. When I finished the story, I couldn’t speak, I just thought to myself remembering the time before I read the story, who I was then, a couple hours ago.

In it, a man sees a "therapist" (a word he later changed to "analyst"), finds it useless, and, without alternative, decides to kill himself. In BOX 24, at the top of the first page of this first handwritten draft is "FRAUD" followed by, "This is the bad part, the foggy part where there's way more than I can ever make you see." Wallace, and the reader, has no choice but to go on.

In different pen colors, blue to black to red to green, the story gets better, shorter, fuller. Where there was once an "analyst" with a "mustache", there is later an "analyst" with a "small ginger mustache", a mustache that is likely taken seriously by its owner and not by anyone else. In his revisions, Wallace would not only correct himself but comment, taunt. Unsatisfied with the first few pages, he wrote at the top of four above the first line, "(I know this part is boring and probably boring you, but it gets a lot more interesting after I kill myself)." This aside made it into the final version of the story. But even the thin sheen of self-defacing humor fades away: "Everything gets so abstract all this free-writing I can't be bothered to even type up. We tried to bombard our problems with will power instead of bringing it into alignment with God’s intention for us." Wallace did not write or talk in extremes, he lived in them.

"Good Old Neon" ends with an oracular exhale, a portion of prose that makes the reader at once alive, aware, terrified, and tired. After going over it for probably the hundredth time, he wrote in a tidy box, "incoherent, but moving." The story is dense, bleak, again necessary, but not incoherent. The last line on that page is also that, "[Ghosts talking to us all the time—but we think their voices are our own thoughts.]" It is no longer the "I" of the protagonist, or the writer, but a "we" that includes us in the nightmare, a self-imposed nightmare, though it feels inevitable.

At the start of the week, in BOX 31, I sifted through an assortment of Wallace gems. In a 70-page, one-subject notebook called "Midwesternisms", he wrote down verbal tics like "because you know why?" "I had a circumstance happen" and "Just let them get it under their belt and chew on it a while." Later, a list of "Good names", among them '1st name: Tova', 'Pat Rexroat' and 'Elpidia Carter.'" On college tests, professors cooed, "un plaisir, mon vieux" and "I am particularly impressed by your thoroughness." Then, amidst the praise was a page ripped from a spiral notebook with the date "7/31/96" in the top left-hand corner. July 1996 was six months after the release of Infinite Jest, at the height of its praise, a thousand page text that was being lauded as an Important Work, a Big Book. A time most would consider the culmination of a young writer's career. At that time he wrote, "The thing is I get scared it won’t come. I'm back to thinking IJ was a fluke." Then, "'Until there is commitment, there is only ineffectiveness, delay.' - Goethe How to make a commitment – to writing, to a somewhat healthy rltp, to myself."

At the end of this entry, in a journal he felt it was not fit for, was this:

What balance would look like

2-3 hours a day in writing

Up at 8-9

Only a couple late nights a week

Daily exercise

Minimum time spent teaching

2 nights/week spent w/other friends

5 AA/week Church

This was the balance he sought, the life he needed. But a towering intellect does not always come with a rock-hard disposition, a disposition to match a brain like Wallace's. In his writing, and in his archives, he was always battling himself, playing himself in a mental tennis match. His archives show that that match was exhausting, tragic, joyous, and now endless.

I visited my friend at Sarah Lawrence in October 2008 just weeks after Wallace’s death. Many on campus were still in mourning, talked about him as if he was a close friend they'd all lost. I knew who he was, had seen a big blue paperback of his on people’s shelves a few times before, had picked it up once to see how heavy it was. When I asked people why they were so upset they could only respond with their own question: "Have you read him?" I hadn't.

I visited my friend at Sarah Lawrence in October 2008 just weeks after Wallace’s death. Many on campus were still in mourning, talked about him as if he was a close friend they'd all lost. I knew who he was, had seen a big blue paperback of his on people’s shelves a few times before, had picked it up once to see how heavy it was. When I asked people why they were so upset they could only respond with their own question: "Have you read him?" I hadn't.

I then tried unsuccessfully to read that big blue book, Infinite Jest. I failed for the same reasons many people do: the footnotes were burdensome, the first 250 pages were dense and largely unconnected. Feeling defeated, I tried semi-successfully to read Brief Interviews With Hideous Men. I finished it, engaged with it, though felt that there were long stretches where I would drift, where I felt I was being forced to endure linguistic acrobatics. It was his nonfiction — arguably his more accessible work — that was my entry point. I’ve since reread his fiction and cherish it all (including Infinite Jest) for its richness, its complexities, for the fact that his voice is at once ours and uniquely his. So, to explore his archives seemed the closest thing to spending time with a person you love and admire, though you don’t know, and never will.

Sitting there, in the Harry Ransom Center, felt like a religious experience. I had an HB pencil (no ink allowed), yellow computer paper, and those thirty-four boxes (though only one at a time). I could not decide if I wanted to listen to my iPod or not as I didn't want to taint his words, to change their meaning by mingling them with song lyrics. Many times, I had physical reactions to what I was reading. Goosebumps. Sweat. A heaviness in my legs. I would catch myself laughing aloud but only because three people were staring at me. It was embarrassing, having these personal responses among eighty year-old academics, chatty librarians, bored sophomores working the front desk. That week, there were so many of those moments where you see or hear something you know is vital, life giving, and say to yourself, "This is one of those." And all you can really say is thanks. Thanks so much.

Jesse Klein is the senior contributor to This Recording. He is a writer and filmmaker living in Austin. He last wrote in these pages about Trent Reznor. You can find his previous work on This Recording here. He twitters here and tumbls here.

"Where You Are" - The Submarines (mp3)

"Birds" - The Submarines (mp3)

"A Satellite, Stars, and an Ocean Behind You" - The Submarines (mp3)