BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Find You Something To Read This Summer

Tuesday, June 21, 2011 at 11:17AM

Tuesday, June 21, 2011 at 11:17AM

Summer Reading

by JANE HU

This is the first in a series.

Middlemarch by George Eliot

I know. You're thinking, "Duh." I know. But I had not read Middlemarch until this summer. It always loomed before me in its sheer and sprawling magnitude, which is also what makes it the paradigmatic summer read. Dorothea Brooke quickly becomes a commonplace in any book-nerd’s vocabulary, but she’s not by any means the only actor in Eliot’s novel. There's Tertius Lydgate — the over-ambitious doctor whose dreams begin to unravel, rather tragically, from the start — and Casaubon, who, presented before any romantic girl, should invoke all the important questions (“How very ugly Mr. Casaubon is!”; “Mr. Casaubon is so sallow”; “Has Mr. Casaubon a great soul?”). Even small characters round out, if only due to the imaginative range inspired by Eliot’s sympathetic eye. Not only witty and intelligent, Eliot is endlessly mature in her insights. The sentences that make Middlemarch a page-turner are also nuggets of enlightened gold.

I know. You're thinking, "Duh." I know. But I had not read Middlemarch until this summer. It always loomed before me in its sheer and sprawling magnitude, which is also what makes it the paradigmatic summer read. Dorothea Brooke quickly becomes a commonplace in any book-nerd’s vocabulary, but she’s not by any means the only actor in Eliot’s novel. There's Tertius Lydgate — the over-ambitious doctor whose dreams begin to unravel, rather tragically, from the start — and Casaubon, who, presented before any romantic girl, should invoke all the important questions (“How very ugly Mr. Casaubon is!”; “Mr. Casaubon is so sallow”; “Has Mr. Casaubon a great soul?”). Even small characters round out, if only due to the imaginative range inspired by Eliot’s sympathetic eye. Not only witty and intelligent, Eliot is endlessly mature in her insights. The sentences that make Middlemarch a page-turner are also nuggets of enlightened gold.

A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh

Waugh came to resent the fact that Brideshead Revisted was his most celebrated book. The lush sentimentality of Brideshead makes it the novel most unlike his others. Nearly two decades after its publication, Waugh would do, perhaps, what he does best: satirize the extravagant manor drama in the conclusion to his war trilogy, Sword of Honour.

Waugh came to resent the fact that Brideshead Revisted was his most celebrated book. The lush sentimentality of Brideshead makes it the novel most unlike his others. Nearly two decades after its publication, Waugh would do, perhaps, what he does best: satirize the extravagant manor drama in the conclusion to his war trilogy, Sword of Honour.

The savage ironist comes out with both pistols cocked in A Handful of Dust. Tony and Brenda are married, but that doesn’t stop Brenda from her affair with John Beaver. Lies accumulate and both sides seem to know the score, but that doesn’t stop them from keeping up all pretenses to sincerity. There will be jokes you’ll want to retell your friends — jokes that will make you (I swear!) LOL — but these won’t translate well out of context. They’ll just have to read the whole damn thing themselves.

The Heat of the Day by Elizabeth Bowen

Incidentally, Tessa Hadley recently recommended this novel on her list, Five Best Books: Betrayals of Love. One would be remiss not to agree with Hadley: The Heat of the Day is most strikingly a love story. But it is also a postwar narrative, stitched with the precarious threads of paranoia, espionage, interrogation, and, yes, finally betrayal. Bowen places her characters amid the foggy hours of summer’s dusk, where a step toward the bar means to risk confessing — or leaking — too much information.

Incidentally, Tessa Hadley recently recommended this novel on her list, Five Best Books: Betrayals of Love. One would be remiss not to agree with Hadley: The Heat of the Day is most strikingly a love story. But it is also a postwar narrative, stitched with the precarious threads of paranoia, espionage, interrogation, and, yes, finally betrayal. Bowen places her characters amid the foggy hours of summer’s dusk, where a step toward the bar means to risk confessing — or leaking — too much information.

As heroine of this detective tale, Stella Rodney exemplifies the double agent: torn between Nazi spy Robert Kelway and his pursuant, the counter-espionage agent Robert Harrison. Bowen’s choice of names does not, of course, result from carelessness. The entire novel rivets the reader with twisting wordplay that makes the text itself into a document to be scanned with scrutinizing care.

Less than Angels by Barbara Pym

There are a lot of modernist lady writers who have unjustly fallen out of vogue, print, and the ever-contemporizing discourse on the canon (which says, really, so much about the canon). It’s not just that a lot of intelligent texts penned by women have been prematurely left behind, but also that so much delightfully entertaining literature has been kept from our hungry eyes.

There are a lot of modernist lady writers who have unjustly fallen out of vogue, print, and the ever-contemporizing discourse on the canon (which says, really, so much about the canon). It’s not just that a lot of intelligent texts penned by women have been prematurely left behind, but also that so much delightfully entertaining literature has been kept from our hungry eyes.

Less than Angels is an academic satire on a group of anthropologists at the African Institute in London and it is better written, smarter, and sharper than that other one (Lucky Jim). If writing today, Pym might disseminate some sassy social commentary on a blog that would, each time, tap into a cultural tic. It’s not too late, though, to read her now.

The Comfort of Strangers by Ian McEwan

The Comfort of Strangers is a slim book, but that’s not the reason anyone reads something ten times. No matter how familiar, McEwan’s sentences keep on giving. Each time you return to Mary and Colin lounging in their Venetian hotel, you’ll be charged with a greater sense of uncertainty and anticipation despite how — or more likely because — you know the ending. He’s a writer who can do that. Every new detail will slice deeper as the prelude to an impending break from innocence.

The Comfort of Strangers is a slim book, but that’s not the reason anyone reads something ten times. No matter how familiar, McEwan’s sentences keep on giving. Each time you return to Mary and Colin lounging in their Venetian hotel, you’ll be charged with a greater sense of uncertainty and anticipation despite how — or more likely because — you know the ending. He’s a writer who can do that. Every new detail will slice deeper as the prelude to an impending break from innocence.

Taking directly from Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, McEwan lures his lovers into the same labyrinthine city and subjects them to an infusion of pornography, sex, and carnality that, at times, resembles a Lynchian daydream. A heat emanates from the novel — interwoven with a blur of white linen — that might make your beach experience seem relatively cooler.

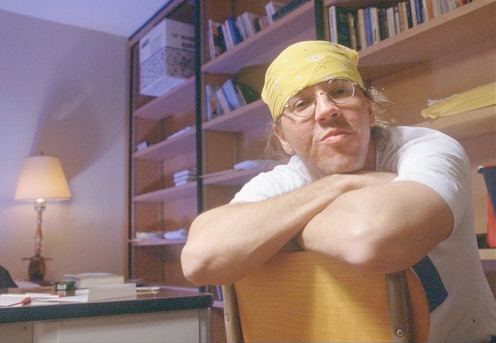

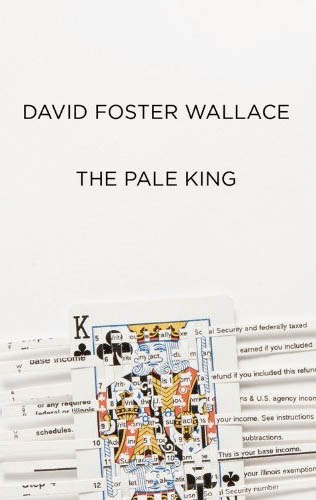

Girl With Curious Hair by David Foster Wallace

“Everything is Green” — a short (short!) story in the collection titled above — was the first thing I ever read by Wallace. It is also my favorite thing by him. Those 700 or so words are like panacea for the heart. They will make you feel things you thought your ironic, discerning, postmodern non-self no longer had the fragility to feel. Those last three sentences will knock you about a bit and leave you searching for those lost pieces that will help recall your vulnerability again. Wallace is at his best when he intimates that love still has the capacity to make one culpable — for potentially anything or anyone — in this world.

“Everything is Green” — a short (short!) story in the collection titled above — was the first thing I ever read by Wallace. It is also my favorite thing by him. Those 700 or so words are like panacea for the heart. They will make you feel things you thought your ironic, discerning, postmodern non-self no longer had the fragility to feel. Those last three sentences will knock you about a bit and leave you searching for those lost pieces that will help recall your vulnerability again. Wallace is at his best when he intimates that love still has the capacity to make one culpable — for potentially anything or anyone — in this world.

Aside from “Everything is Green,” the other stories are punctuated with subtitles or historical quotes from magazines that make them perfect for reading in transit. Once, immersed in “Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way” (the longest of them all), I started riding the same line back and forth, end to end, in order to finish it. I probably should have just gotten off, but Wallace’s words are terribly conducive to motion. Sentences like “The lover tries to traverse: there is motion of travel, except no travel,” while seductively ambiguous, are also profoundly tender. In "Little Expressionless Animals,” Alex Trebek asks, "Is there such a thing as an intellectual caress?" Yes! Certainly! But, don’t forget, Wallace goes far beyond the head. A Wallace’s sentence is perpetually "giving up its shape in a gesture that expresses that shape. See?" So that content— thought — becomes also a gesture, a caress.

Wonder Boys by Michael Chabon

Wonder Boys might be the darker companion piece to Out of Sheer Rage on this list. Both narrators seek to complete their magnum opuses. Both recognize, rather openly, how this more or less won’t happen. Both continue onwards with the task. It is this persistent faith — overpowering all futility and shame — which makes Chabon’s protagonist and Dyer’s narrator both so exasperatingly sympathetic.

Wonder Boys might be the darker companion piece to Out of Sheer Rage on this list. Both narrators seek to complete their magnum opuses. Both recognize, rather openly, how this more or less won’t happen. Both continue onwards with the task. It is this persistent faith — overpowering all futility and shame — which makes Chabon’s protagonist and Dyer’s narrator both so exasperatingly sympathetic.

Like Dyer’s book, Wonder Boys is madly playful, but Chabon makes his protagonist even more self-willed in his delusions that, because we grudgingly care about him, it often hurts. Grady Tripp embodies the despondent professor and fading author as he blunders through Chabon’s campus novel, besieged by his own self-contradictions. At first I think I hate him, but then he opens his mouth and says something beautiful.

Out of Sheer Rage: Wrestling with D.H. Lawrence by Geoff Dyer

Dyer’s pseudo-memoir begins with aims to tackle an academic book on D. H. Lawrence, and amounts to a 232 page first-person narration of this maddening tussle. While Lawrence’s name appears on nearly each page, the novel is only tangentially about the author. Dyer is too distracted and restless to get down to the task of writing, so he goes travelling instead, bounding back and forth between London, Rome, Paris, Greece…unable to settle anywhere for long since stillness immediately brings only dissatisfaction. We follow the breathless pace of his mental and physical journey (where not much, honestly, happens) eagerly. The book is a viciously funny monologue — a couple hundred pages of exquisitely readable whining. It’s also a travelogue, punctuated by rather stunning philosophical insight and sometimes, goodness forbid, even literary criticism.

Dyer’s pseudo-memoir begins with aims to tackle an academic book on D. H. Lawrence, and amounts to a 232 page first-person narration of this maddening tussle. While Lawrence’s name appears on nearly each page, the novel is only tangentially about the author. Dyer is too distracted and restless to get down to the task of writing, so he goes travelling instead, bounding back and forth between London, Rome, Paris, Greece…unable to settle anywhere for long since stillness immediately brings only dissatisfaction. We follow the breathless pace of his mental and physical journey (where not much, honestly, happens) eagerly. The book is a viciously funny monologue — a couple hundred pages of exquisitely readable whining. It’s also a travelogue, punctuated by rather stunning philosophical insight and sometimes, goodness forbid, even literary criticism.

At one point, Dyer questions the novelistic form, as he yearns for something more compatible with lived experience: notes, letters, thoughts that exemplify the act of becoming rather than retrospectively pieced-together states of being. His phrases reenact the errant (and frequently banal) movements of self-destructive behavior in ways that are therapeutic to the reader and, presumably, also writer. He wishes the book to be “not a history of how I recovered from a breakdown but of how breaking down became a means of continuing.” It’s not merely “look-no-hands” prose, for we actually believe Dyer in his aimless, sometimes careless, search for faith from unexpected sources. Finally, you will laugh.

The Giant, O'Brien by Hilary Mantel

Are you fascinated with lists? Tabulations? Catalogues? Collectors? Hunters? Binomial nomenclature? Language systems? Historical fiction set in the 18th century London (but written in the 1990s)? Enlightenment ideals? Giants? Freaks? Monsters? Frankenstein? Diseases? Bodies? Animal fables? Sapient pigs? The distinctions between moral pain, physical pain, and emotional pain? The very history of pain? The incommunicability of pain? Regarding the pain of others? Allusions? Expostulations on print capitalism and commodity culture? Ireland? Or perhaps Scotland? Medicine? Experiments? Surgery? Corpses? Crimes? Bioethics? Torture? Cruelty? Sex? Science? Wonder? Magic? Cures? The afterlife of pain? The afterlife itself? Whichever way you spin it, Mantel’s stories nearly recommend themselves. The novel stitches together the narratives of the eponymous Giant and a scientist-of-questionable-ethics John Hunter. It will be unlike anything you have ever encountered.

Are you fascinated with lists? Tabulations? Catalogues? Collectors? Hunters? Binomial nomenclature? Language systems? Historical fiction set in the 18th century London (but written in the 1990s)? Enlightenment ideals? Giants? Freaks? Monsters? Frankenstein? Diseases? Bodies? Animal fables? Sapient pigs? The distinctions between moral pain, physical pain, and emotional pain? The very history of pain? The incommunicability of pain? Regarding the pain of others? Allusions? Expostulations on print capitalism and commodity culture? Ireland? Or perhaps Scotland? Medicine? Experiments? Surgery? Corpses? Crimes? Bioethics? Torture? Cruelty? Sex? Science? Wonder? Magic? Cures? The afterlife of pain? The afterlife itself? Whichever way you spin it, Mantel’s stories nearly recommend themselves. The novel stitches together the narratives of the eponymous Giant and a scientist-of-questionable-ethics John Hunter. It will be unlike anything you have ever encountered.

The Complete Letters of Henry James: Vol 1 & 2

James wrote a lot of beautiful novels, but most of them might stand to be too meandering in their verbosity and too static in their action to amount to any riotous summer reading. Letters are my answer to bite-sized James without being sacrilegious (anyway, it’s rather unimaginable that anyone might abridge him). James wrote a lot of beautiful novels because, well, everything that man touched turned to crystal-refracted insight, so you can damn well bet that the letters are better prose than most could ever dream up, given infinite time, a keyboard, and a backspace. “There’s no telling where my pen may take me,” he muses to his mother in 1869.

James wrote a lot of beautiful novels, but most of them might stand to be too meandering in their verbosity and too static in their action to amount to any riotous summer reading. Letters are my answer to bite-sized James without being sacrilegious (anyway, it’s rather unimaginable that anyone might abridge him). James wrote a lot of beautiful novels because, well, everything that man touched turned to crystal-refracted insight, so you can damn well bet that the letters are better prose than most could ever dream up, given infinite time, a keyboard, and a backspace. “There’s no telling where my pen may take me,” he muses to his mother in 1869.

Describing the American individual, James writes, “There is but one word to use in regard to them — vulgar, vulgar, vulgar. Their ignorance — their stingy, defiant grudging attitude towards everything European— their perpetual reference of all things to some American standard or precedent which exists only in their own unscrupulous wind-bags—and then our unhappy poverty of voice, of speech and of physiognomy—these things glare at you hideously.” (Other times he checks himself: “But I must stay my gossiping hand. . . .”) But James was a grand American—the best kind there is; the type that leaves America for some time. Frequently, James would sign off: “Thy lone and loving exile.” Beyond all this, his correspondences offer a counterpoint to James as the mythic man of studious seclusion, where one can experience — almost unmediated — the reeling joy, the vitalizing discernment, that is so crucially tied to his genius.

Netherland by Joseph O'Neill

For many, the defining feature of Netherland is its status as a post-9/11 novel. Others emphatically describe it as first and foremost a postcolonial re-writing of The Great Gatsby. It’s also a detective story set in the dazed summer months. Hans van der Broek — Dutch-born American immigrant — is left in New York by his London-bound wife and son. He subsequently befriends Chuck Ramkissoon, an American dreamer from Trinidad. However you read it, Netherland is politically thoughtful, while also rhetorically sensitive and stunning.

For many, the defining feature of Netherland is its status as a post-9/11 novel. Others emphatically describe it as first and foremost a postcolonial re-writing of The Great Gatsby. It’s also a detective story set in the dazed summer months. Hans van der Broek — Dutch-born American immigrant — is left in New York by his London-bound wife and son. He subsequently befriends Chuck Ramkissoon, an American dreamer from Trinidad. However you read it, Netherland is politically thoughtful, while also rhetorically sensitive and stunning.

O’Neill handles Hans’s ethical impasses (no matter how confusedly they compound) with quiet sympathy, and treats cricket as the moral barometer that might finally redeem us. If so many “readable” novels don’t leave enough breathing space to let you simply think, then Netherland is an exception: “I was bowled over. I had never considered the possibility of undiscovered factors.” What the novel says is underpinned with the swiftest strokes of intelligence — a plurality of “factors.” Yet, how it is said never fails to move on an individual level. Be careful. You might end up feeling the right emotions for the wrong reasons.

Gate at the Stairs by Lorrie Moore

In the fall of third year, I took to putting those accumulating New Yorkers to use and began toting them to the gym. I’d ride the elliptical and read until either the machine or the small print wore me out. I’d stumble along the treadmill while quietly mouthing Sam Shephard’s dialogue. It was through this routine that I discovered Moore’s story "Childcare", which had, by the time of my reading it, been expanded into a novel, The Gate at the Stairs. This I would not have promptly registered had I not been so enraptured with Moore’s protagonist, Tassie Keltjin, as to Google her. Needless to say, the novel was bought. It’s a Chekhovian bildungsroman set in the American Midwest — this generation’s version of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn for small town 20-somethings.

In the fall of third year, I took to putting those accumulating New Yorkers to use and began toting them to the gym. I’d ride the elliptical and read until either the machine or the small print wore me out. I’d stumble along the treadmill while quietly mouthing Sam Shephard’s dialogue. It was through this routine that I discovered Moore’s story "Childcare", which had, by the time of my reading it, been expanded into a novel, The Gate at the Stairs. This I would not have promptly registered had I not been so enraptured with Moore’s protagonist, Tassie Keltjin, as to Google her. Needless to say, the novel was bought. It’s a Chekhovian bildungsroman set in the American Midwest — this generation’s version of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn for small town 20-somethings.

Full of lyrical turns and natural imagery, The Gate at the Stairs is compelling even when depicting the most quotidian phenomena. Tassie goes to college and babysits a recently adopted mixed-race baby. She falls in love, sort of. She grows up. Sort of. The most common criticism of Moore’s novel is that Tassie sounds wildly wise beyond her years — her voice is too witty, too mature, too world-weary. But, I’m thinking, “Nah, girls are sad when they’re twenty. They frequently long to feel heavy. At least I did.” For me, Moore got Tassie right.

Jane Hu is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer currently based in Berlin. She tumbls here. She last wrote in these pages about her favorite novels.

"Slow Motion" - Patrick Wolf (mp3)

"The Days" - Patrick Wolf (mp3)

"Time of My Life" - Patrick Wolf (mp3)

More Books To Fill Your Idle Time

Part One (Tess Lynch, Karina Wolf, Elizabeth Gumport, Sarah LaBrie, Isaac Scarborough, Daniel D'Addario, Lydia Brotherton, Brian DeLeeuw)

Part Two (Alice Gregory, Jason Zuzga, Andrew Zornoza, Morgan Clendaniel, Jane Hu, Ben Yaster, Barbara Galletly, Elena Schilder, Almie Rose)

Part Three (Alexis Okeowo, Benjamin Hale, Robert Rutherford, Kara VanderBijl, Damian Weber, Jessica Ferri, Britt Julious, Letizia Rossi, Will Hubbard, Durga Chew-Bose, Rachel Syme, Amanda McCleod, Yvonne Georgina Puig)