BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Read To Live And Vice Versa

Monday, July 4, 2011 at 9:35AM

Monday, July 4, 2011 at 9:35AM

Summer Reading

by KARA VANDERBIJL

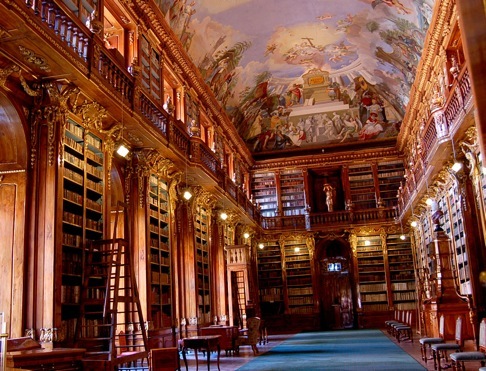

It seems unnatural to read in the summer, when the only thing keeping us inside is the occasional electric storm. That is why it is of utmost importance that we find the books that enhance our experience of it rather than taking us outside of it. There are books that would prolong your best vacations and pillow your head in the sand. Do not read anything that you will take seriously. If you must, purchase a book on tape and listen to it while in your vehicle en route to a campsite in Vermont. The machines that keep us alive throughout the rest of the year become obsolete in these warm months. We are quick to believe the same of books. In reality this is the most beneficial time to read, outside the constraints of academic or meteorological obligation.

Childhood by Nathalie Sarraute

Childhood by Nathalie Sarraute

Most memoirs of childhood are summer watercolors. When we were children, summers were long — or at least we remember them as such. Most of Sarraute’s autobiography, penned when she was over eighty years old, takes place in the winter. Within it she converses with a failing memory. Questioning the significance of events one must recall using secondary sources or reconstruct with logic, she shares all the sensations of her earliest recollections: the color of a sofa she destroyed with a pair of scissors, the cool indifference of her mother.

Sarraute’s tendency to bend literary convention shines through in this, her last of works, as she uses her own life story to question the human ability to remember. Because she does not know for sure that the events of her childhood happened in the sequence or in the manner she recalls, she must use the gift of invention to create a life for herself.

Book of My Mother by Albert Cohen

Book of My Mother by Albert Cohen

Cohen disguises his memoir as a eulogy to his mother, which will irk you slightly as the book progresses. I had no trouble finishing this short reminiscence of a move from Corfu to Marseille, of marginalization as foreigners, of the complex relationship between a Jewish male and his mother — but I did have trouble liking Albert all the way through.

His mother represents nothing less than a female ideal, the connection to another world and the safety of traditions; his regrets about their relationship read like the ranting of a lovelorn teenager. One particularly poignant moment describes Cohen’s embarrassment about his mother’s accent and her insistence on knowing his whereabouts at all times. His shame transforms her into a bizarre conglomeration of the Madonna bending over her child in simple adoration, and of the Christ with stigmata. Plow through the overwhelming waves of sentimentalism to find his purpose; the story will soothe any tension out of a family vacation.

Losing North by Nancy Huston

Losing North by Nancy Huston

“To be disoriented is to lose the east,” roughly translates the first line of Huston’s book. This is familiar to me. To lose the east in Chicago is to forget, almost absolutely, where anything is. Earlier I was trying to find a popular Italian ice shop in the neighborhood. “Where is the lake?” my companion reminded me gently when I very nearly lost my head at an intersection. We followed the grid of this city back to its steel giants and remembered. You will relate to Huston’s small essay best if you are a third culture kid, but even a small trip overseas will affirm the brilliance of its thoughts on the mottled cultures and languages of the expatriate.

Huston expresses this jet-lagged sense of vertigo better than any other writer I have encountered. She plays with her bilingualism like other writers play with literary allusion, claiming to have found her voice when she mastered French during her years at a Canadian university. As the most empathetic and amusing of travel writings, it should find its way into your carry-on.

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert translated by Francis Steegmuller

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert translated by Francis Steegmuller

It is becoming apparent that I am incapable of reading anything in the summer that was not first written in French. What Flaubert’s letters say about him and the intricacy of his art delights anyone who has spent significant time reading his novels. “I’ll try to arrive some evening about six,” he writes to Louise Colet, his longtime lover. “We’ll have all night and the next day. We’ll set the night ablaze! I’ll be your desire, you’ll be mine, and we’ll gorge ourselves on each other to see whether we can be satiated. Never! No, never! Your heart is an inexhaustible spring, you let me drink deep, it floods me, penetrates me, I drown. Oh! The beauty of your face, pale and quivering beneath my kisses!” Tell me if you can find the same man in these pages as the one who knew how to best kill his darlings.

The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson

The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson

To read this fascinating account of the World’s Fair and the people who had a hand in it is to become a true Chicagoan, I soon found out. Not for the faint of heart, Larson’s book follows the architects who built the fairgrounds — the “White City” — as well as America’s first serial killer, H.H Holmes, who victimized young women at the fair.

Do not pretend you are not fascinated with death and the men who choose to bring it upon others. Why would Larson choose to parallel the creation of a monster and the creation of the World’s Fair? The comparison is obvious — men at their best, men at their worst — and it employs all the good-versus-evil jargon we appreciate in a summer read.

Jealousy by Alain Robbe-Grillet

Jealousy by Alain Robbe-Grillet

Robbe-Grillet returns to one particular scene repeatedly in his novel: on a tropical veranda, a husband observes his wife and their neighbor, hidden in the penumbra whispering while ice cubes melt in their glasses. Although the tale rests on that most piercing of suspicions — the suspicion of unfaithfulness — Robbe-Grillet visits the setting more often, describing in painstaking detail the banana plantation, the way the sunlight hits shaded windows and angles on the grass.

This hostile environment, and the constant revisiting of the moment on the veranda, illumines the husband’s jealous obsession, as much as Desdemona’s handkerchief did for Othello. There is quite a bit of fruit in this novel. Is it possible to eat anything else in the summer? Very little satiates in the heat except the inkling that some other truth lurks beneath the details of the tiles underfoot, the soft linens of your clothing and the exchange of words in a moist evening. The dialogue in the novel rings false, but what is there to be said in August?

The Help by Kathryn Stockett

The Help by Kathryn Stockett

Some Southern acquaintances were telling me about how you cannot live in downtown Charleston unless you are of old money, and then proceeded to laud the Confederate flag. This story should be lesson enough to read Stockett’s literary debut, should you read any bestseller in the next months. It alternates between the first-person narratives of privileged white females and their black maids in 1960s Mississippi, thus exploring civil rights on almost every level of society.

There are practically no male characters in this book, but I have not yet decided whether or not Stockett did this on purpose or whether she does not know how to write them. What the novel lacks in profundity it makes up for with its unabashed treatment of themes we thought to let lie at rest forever with Harper Lee. Read it before August 12th, and then go cool off in a dark theatre with the movie.

O Pioneers! by Willa Cather

O Pioneers! by Willa Cather

The land is a wild, unpredictable thing, which you will forget until you run out of gas somewhere in West Texas with no Dairy Queen in sight. In Cather’s short masterpiece, several immigrant families attempt to tame it. Two characters share the kiss of infidelity at a gypsy wedding. People die off regularly, and a kitten is rescued in the first few pages. Must I convince you of its other merits? I do not know if you have been to a place lacking in human presence, but I have. It is a frightening thing to be alone with nothing but the sky.

What Cather’s characters dream of most is security and protection — the very things that the earth cannot give them, and that their conflicts prohibit them from giving to each other. We do not love this book as much as we love Cather’s My Antonia, because we have forgotten what it is like to want soil and to live at the mercy of the land. In writing about people that are strange to us in culture and desire, Cather reminds us of our roots.

Kara VanderBijl is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Chicago. You can find an archive of her work on This Recording here. She last wrote in these pages about Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris. You can find her website here.

This is the fourth in a series. You can read the first part here and the second part here. You can read the third part here.

jayne mansfield

jayne mansfield

"Desire (piano demo)" - Alela Diane (mp3)

"Long Way Down (acoustic demo)" - Alela Diane (mp3)

"Eastward Still" - Alela Diane (mp3)

Our Novels, Ourselves

Part One (Tess Lynch, Karina Wolf, Elizabeth Gumport, Sarah LaBrie, Isaac Scarborough, Daniel D'Addario, Elisabeth Donnelly, Lydia Brotherton, Brian DeLeeuw)

Part Two (Alice Gregory, Jason Zuzga, Andrew Zornoza, Morgan Clendaniel, Jane Hu, Ben Yaster, Barbara Galletly, Elena Schilder, Almie Rose)

Part Three (Alexis Okeowo, Benjamin Hale, Robert Rutherford, Kara VanderBijl, Damian Weber, Jessica Ferri, Britt Julious, Letizia Rossi, Will Hubbard, Durga Chew-Bose, Rachel Syme, Amanda McCleod, Yvonne Georgina Puig)

Why and How To Write

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Gene Wolfe, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, Robert Creeley, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Lyn Hejinian, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)

kara vanderbijl,

kara vanderbijl,  summer reading

summer reading