BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Become A Mystery To Ourselves

Monday, April 30, 2012 at 11:54AM

Monday, April 30, 2012 at 11:54AM

I Sometimes Really Feel That Way

by ALICE BOLIN

My first day teaching creative writing to middle schoolers, I walked into the room where my class would meet, normally a health classroom, and found a large piece of butcher paper taped to the blackboard. Written in teacher handwriting across the top of the paper was the question “WHAT IS UNINTENTIONAL INJURIES.” I was on my laptop, trying frantically to record all the examples of unintentional injuries that had resulted from the health class’ brainstorm (“to accidently drop a baby,” “committing suicide on accident,” “accidentl death”), when my group of eighth graders started trickling into the classroom.

There I was, strange adult, rapt by the results of a seventh grade health class activity and clearly taken off guard by their appearance in my classroom. The eighth graders didn’t laugh at me, didn’t even smile, only stared at me skeptically. I scrambled to put my computer back in my bag and stand at the front of the room like some sort of authority, but the damage was done — it is a particular kind of indignity to be regarded as freakish by a group of nerdy pre-teens, one of whom is actually named Anakin.

There was just no way to explain to them what I was doing. “Look at this thing,” I said, pointing to the butcher paper. “Isn’t it funny?” They only eyed me more dubiously. In my first act as their teacher, I had inadvertently revealed my strongest personal compulsion, which is to hoard verbal matter, overheard conversation, stray remarks, stray thoughts, notes, lists, e-mails, gchats, text messages, diaries, notebooks, any and every piece of paper on which something mysterious or funny is written.

For instance: I have in my pocket at this moment a note I don’t remember writing to myself that I found recently on my floor. It reads, “Landscape quote: O pardon me thou bleeding piece of Earth.” (Googling reveals this is from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.) Also in my pocket is a note card where it says in my graduate thesis advisor’s handwriting, “Question / Is there a historical reason for the great number of rear/alley entrances/exits in Missoula bars?” Also: a stranger’s to-do list I found tucked in a book I ordered online; its only noteworthy item is “Return Cal’s pants!”

Why I keep these things, why I needed to document “What Is Unintentional Injuries,” why I write down any interesting group of words that I hear or see, even just phrases that materialize in my brain suddenly but insistently — it is impossible to account for this practice completely, even to myself. As Joan Didion writes in her essay “On Keeping a Notebook,” “The impulse to write things down is a peculiarly compulsive one, inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself.”

The easy justification, the one Didion is referring to, is that these random words might some day make it into a piece of writing, and of course they might. But I can tell you this happens for me remarkably rarely: the sentences I treasure most as found artifacts do not transform gracefully to components of writing, either poetry or prose, that could be judged as traditionally “good.” For over a year I kept a file on my computer where I recorded my most emphatic thoughts, in an attempt to identify my mental refrains. I believed this file might become a useful reserve of poetic lines; instead it only serves to illustrate my incredibly vulnerable self-talk.

“Why do I keep forcing myself to think about this?” reads one item in the list. Another reads, “I have to not think about it.” “We have all learned to ignore it” and “It’s no one’s fault,” read others. There are pleas: “Don’t get some other girl.” “Don’t bring your girlfriend.” “Don’t kiss where I can see you.” And confessions: “I’m fairly obsessed with you.” “Sorry I’m so obsessed with you today.” But most of all there are just so, so, so many feelings: “I sometimes really feel that way.” “I am a happy person always.” “I’m always sad, but it’s okay.” “Am I sad or happy?” “I am sad or happy.” “I have no feelings.” “I’m a thing, I’m a feeling.” “I’m a thing.”

Didion also mostly records cryptic phrases, but she relates the strange items that she writes in her notebook as guideposts to memories, the one detail needed to evoke an entire place, time, and mood. The phrase “So what’s new in the whiskey business” written in Didion’s notebook calls to her mind a blonde woman conversing with two fat men by the swimming pool of the Beverly Hills Hotel — an intact context exists in her memory. “'So what’s new in the whiskey business?'” Didion writes. “What could that possibly mean to you?” But for me it is exactly the lost significance, the sentiment that is not meaningless but only unmoored from its origins, that appeals to me about this kind of collecting.

I suppose this can’t be separated from my relationship to poetry: that I love the way that poetry makes words strange and frees everyday speech from its everyday uses. Any carefully written thing can be loved for the beauty and ingenuity of its language, but it is poetry’s main selling point that we may enjoy it at the level of the poem, the stanza, the sentence, the line, the word, the syllable. And much of contemporary poetry is explicitly about divorcing words from their contexts, evoking emotion without a discernible story. So while the sentences I write down rarely become poetry, I have noticed that it is often other people who love poetry who I see also grabbing their notebooks after hearing a startling turn of phrase.

And it is often these same poetry lovers who produce fodder for notebooks: my experience in grad school for poetry was remarkable for the incredible sentences I heard and read delivered offhand. I have recorded in old class notes countless statements like, “Pennies are probably our most happy coins,” “‘I don't want to think about that’ is what my sisters say,” and “Debra says squirrels smell like mice with rotten teeth.” My colleagues annotated my work with comments like “Sexy connotations!” and “I read your movements as ‘begat, begat, begat’ and also ‘subsumes, subsumes.’” Taken in context, none of these remarks are as odd as they seem written here; that’s why it’s so important for me to remove the context, so I can delight in them.

My collecting is not only about enjoying language in its mystery but also becoming a mystery to myself. I often write things on my cell phone’s Notepad feature late at night, when I am half-asleep or drunk, that I puzzle over in the morning. There are two identical entries that say, “Rom com: woman lives in vegas and is a court reporter.” Another: “Hersheys kisses mutant chocolate chip something.” One of the things I am most grateful for in life is to find traces of my own former thought processes and feelings that I could not possibly replicate or inhabit again. I read “I’m fairly obsessed with you” written in the file of my thoughts and I have no idea whom I was addressing.

“We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget,” Didion writes. “We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.” She ignores that to forget can be a supreme grace. I treasure all of the diaries I kept when I was a child precisely because of the distance I feel from the girl who wrote them. Seventh grade Alice: “It’s totally cool because it’s like we’ve moved on to another level of flirting.” Eighth grade Alice: “You know I’ve been thinking way deep things lately.” First grade Alice: “Dear Alice, I don’t know. Love, Alice.”

I have always been a person who is “sensitive,” and I take too long to get over everything. Reading old journals and notebooks, I am reminded that feelings are, in their essence, immediate, and they pass over us like shadows. All the words I collect are artifacts of sentiments that do not exist and could not even be conceived of again — ideas that once desperately needed to be expressed disappear, leaving husks of language that I save, I care for.

Alice Bolin is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Missoula. She last wrote in these pages about baby giraffes.You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She tumbls here and twitters here.

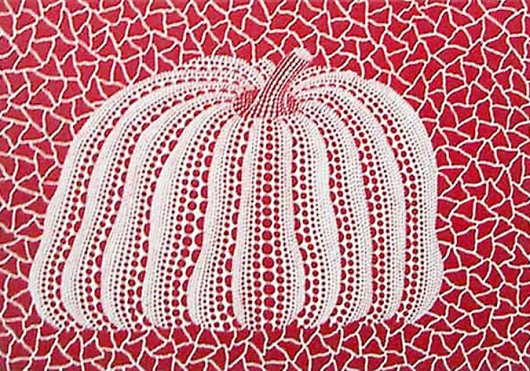

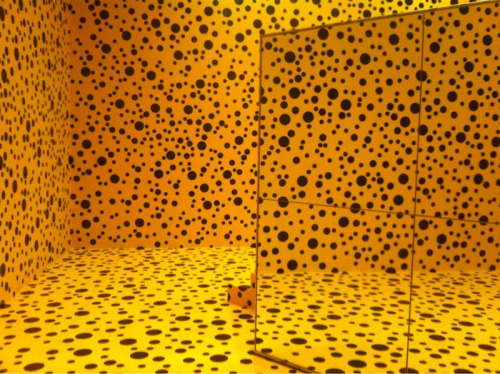

Images by Yayoi Kusama.

"Met Your Match" - Brendan Benson (mp3)

"Thru The Ceiling" - Brendan Benson (mp3)

The new album from Brendan Benson, What Kind Of World, was released on April 21st.

alice bolin,

alice bolin,  joan didion

joan didion