FILM

FILM In Which We Are Feeling A Lot More Solipsistic Than Usual

Wednesday, August 25, 2010 at 10:29AM

Wednesday, August 25, 2010 at 10:29AM

No Room for Muses

by KARINA WOLF

Where else can you be paranoid and right so often?

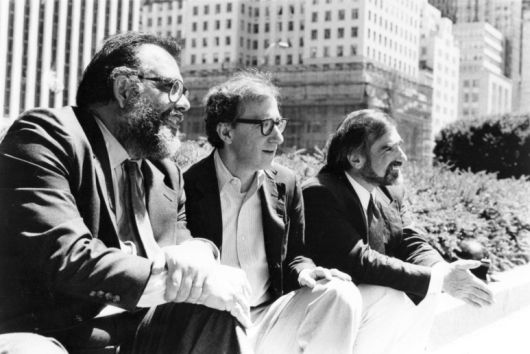

All of Manhattan is Woody Allen’s Manhattan: the reservoir, the restaurants, the skyline, the shrink’s office, the horse and carriage, the modern art, Central Park, Minetta Lane, the Great White Way, the Pierre, and Elaine’s. Most of all, and most importantly, the patois.

New York is a solipsistic, humanistic kind of village. Despite his singularly white and wealthy cast of characters, Woody Allen’s work reflects the way we live and speak. His post-9/11 short, Sounds of the Town I Love, is illustrative: in one-sided phone chats, New Yorkers are narcissistic, petulant, self-serving (the comedy often masks the aggression), hypochondriacal and high-handed. They’re also survivors, with a measure of warmth that keeps them human. They’re all of us.

It’s the idiom that makes Allen believable — that grasping, uncertain mode of talk. When it works, his dialogue is spot on, full of latent aggression and open insecurity. For actors, his words are perfect storms of contradiction. And the delivery, tossed off, half-recalled, is probably the element that allows people to conflate Woody Allen the actor with his characters. His words sound like him, how could this be fiction?

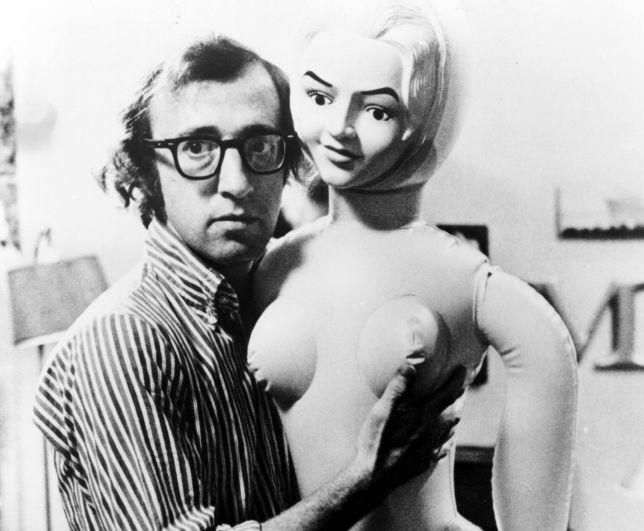

But Allen is a more complicated talent than his hapless schnook act suggests. He’s a comic workaholic, a tireless spinner of jokes, gags, sketches, sex comedies, murder mysteries, chamber pieces, ensemble dramas, fictional biopics, false documentary and ragtime jazz. He’s been at it since he was 15 and commuted from Brooklyn to churn out punch lines for $40 a week. His is a formidable discipline: writing, directing, exercising, practicing the clarinet, going to bed and rising on a precise schedule. Woody Allen leaves no room for muses.

According to Allen, many of his films are unsuccessful in some sense or another, but the work is his goal. Just as his characters seek a meaningful experience of the universe, Allen finds purpose through creativity. He explains why he continues to make films (his latest, Whatever Works, is his 40th): “You don’t think about the outside world, and you’re faced with solvable problems, and if they’re not solvable, you don’t die because of it. And then, if it’s the right film...for several months, I get to live with very beautiful women and very witty men.”

He writes for his limited range as an actor – he says he can play only low lives or intellectuals – but it’s a broad canvas for film: bank heists, mysteries and magic acts for the comedies; adulterous love and morality plays for drama. If he returns to certain motifs, he is a kaleidoscopic innovator. If the wind-up to the jokes seems wordy or his sense of drama derivative, there’s still the inescapable: he’s created a vocabulary for the urban American.

Allen’s art has progressed in leaps – he was dismissed from NYU film school in the 50s, then immediately employed writing for TV. When he moved to filmmaking, he received an on-the-job apprenticeship with some of the world’s finest technicians. Ralph Rosenblum, the editor who cut Annie Hall, taught Allen about shaping a story; Gordon Willis, who lit The Godfather, instructed him in framing a shot. Then Allen moved on to simpatico collaborators who matched his on the fly approach: cameraman Carlo di Palma, for example, who’d arrive on set without knowing the day’s shot list.

With these artisans, Allen created the signatures of his filmmaking: the long takes with little coverage, the amber glow that makes his actors beautiful and his interiors romantic. He claims his aesthetic is borne of practicality. Husbands and Wives, composed with a handheld camera, mid-scene cuts and equally jagged exposures of the human heart, was the result, says Allen, of ‘laziness.’ He didn’t want to be bothered with the formal niceties of American films.

"Can one’s work be influenced by Groucho Marx and Ingmar Bergman?" he ponders in a remembrance of the Swedish director. Allen’s idols are the somber giants of world cinema, and when he stretches himself, it’s because he wants to make the kinds of films that fulfill him: the stark emotional landscapes of Bergman or Kurosawa, the family melodramas of Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller. This attitude may be forged (just as his view of Manhattan was) in the traditions of Hollywood, where comedy is a jester and drama is artistic king. As Eric Lax says, for Allen, the comedy was never disparaged but it certainly was considered a route to drama.

Woody Allen’s descendents are numerous – what contemporary filmic romance doesn’t owe something to Annie Hall? But his movies often subvert the laughs, with Allen supplying happy endings when they disturb and less sanguine ones when they’re hoped for. When a man gets away with murder—and goes unpunished, and feels fine—here, you see his darker view of human nature. “Your mind will never be able to give you a convincing justification for living your life, because from a logical point of view, if your life is indeed meaningless — which it is — and there’s nothing out there, what is the point of it?”

But whatever his diagnosis of humanity, his comedy has healing powers. In a way, the 2002 Oscar ceremony was the world’s reconciliation with Woody Allen. The heart wants what it wants, says Allen, but punishing judgment was passed upon the direction of his desire when he left Mia Farrow for Soon-Yi Previn. More than a decade later, the couple was still together and Manhattan falling apart; the world needed Woody.

His appearance at the Oscars, after he’d so frequently refused to show, was a gesture for survival. Allen introduced some clips about New York and brought the audience to their feet. “I said, 'You know, God, you can do much better than me. You know, you might want to get Martin Scorsese, or, or Mike Nichols, or Spike Lee, or Sidney Lumet...' I kept naming names, you know, and um, I said, 'Look, I've given you fifteen names of guys who are more talented than I am, and, and smarter and classier...' And they said, 'Yes, but they were not available.'" He was transformed from a polarizing figure to a reassuring one. And by remaining recognizably himself, he made New York itself again.

When I saw him perform at the Carlyle, there was a similar elation in the audience. I’ve never felt the same lift as when Woody came out: good will, excitement, childish thrill. The Café Carlyle is café-sized. Every seat was a good seat and from where we perched we could see that Woody was suffering a cold. He stared fixedly at the floor, as a friend who’s worked with him had warned, and he slumped through the beginning of his performance, but roused himself to play the tunes of Jelly Roll Morton. His balding piano player sang “Because My Hair Is Curly,” one of Sam’s comic songs from Casablanca (this, even though Allen has confessed that he doesn’t much like the classic film).

Geoffrey Rush stood at the back, spattered with rain, just in from his Broadway performance of Ionesco. The maitre d’ was unerringly hospitable as we shuffled a wad of dollars to pay the daunting dinner bill. It was a packed house: tourists and Upper East Siders and locals like ourselves, who arrived at Bobby Short Way to listen to the jazz we hear in his films and share a bit of his time. He played for two hours, and left the crowd wanting more: “That’s all folks. I’m going home.” And he wove through the tables, nodding at a few, disappearing, perhaps, to his planned, early bedtime.

Some will say that Allen doesn’t speak for them, or that his films are no longer relevant, no longer funny. But what he’s done is create a consciousness: some of his works shape how we perceive places, people, even feeling. Some of his lessons are so persuasive that you want to be a part of them. In Manhattan, his character constructs a convincing list of things that make life worth living. As viewers, we have the pleasure of adding to that list the films of Woody Allen.

Karina Wolf is the senior contributor to This Recording. She tumbls here and twitters here. Her book The Insomniacs is forthcoming from Penguin Putnam.

"If It's True" - Anais Mitchell (mp3)

"Why We Build The Wall" - Anais Mitchell (mp3)

"Our Lady of the Underground" - Anais Mitchell ft. Ani DiFranco (mp3)