FILM

FILM In Which Her Good Skin Says It All

Thursday, June 2, 2011 at 10:58AM

Thursday, June 2, 2011 at 10:58AM

Carriage Ride

by DURGA CHEW-BOSE

Of Manhattan’s 96 minutes, 25 of them swap comedy for candor and the veneer of midlife fitfulness for a snowy and plainspoken 17-year-old Dalton girl named Tracy. While she only occupies a quarter of the film's runtime - thirteen scenes, one cry, one carriage ride, five toppings on her pie, two close-ups, and the line, "Let's do it some strange way that you've always wanted to do it" - Manhattan belongs to Mariel Hemingway.

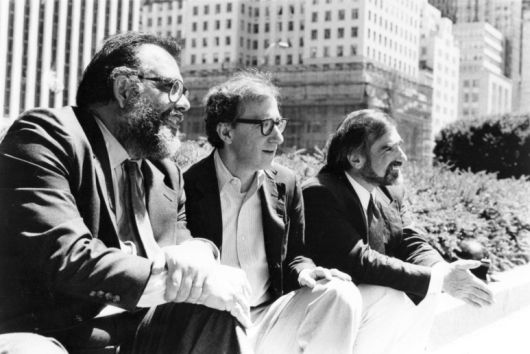

From the moment we see her sitting at Elaine’s with her 42-year-old lover, Isaac (Woody Allen), and his married friends, Yale and Emily, Hemingway typifies teenage limbo: a discomfort with oneself that for a lucky few, can yield the most luminous glow. As Yale waxes about "the essence of art" with Isaac, and as Emily, on cue, rolls her eyes and apologizes, "We've had this argument for 20 years," Tracy smiles and accepts. Her age and inexperience might keep her on the periphery this time, but her silence and presence, and elbows resting keenly on the table, suggest considerable aplomb.

Tanned and wearing a dark crewneck sweatshirt, teardrop necklace, and her hair pulled back in a loose ponytail, Tracy's softness is offset by her sturdiness. She looks like she might have, moments before arriving at Elaine's, practiced her serve and volley in P.E. or finished her lifeguard shift at the local pool. She is incandescent in the summer and dimmed in the winter. She is Coppertone® and Hyannis Port personified.

In a piece titled, "The Littlest Hemingway" in a June 1979 issue of People, Kristin McMurran describes Mariel's first Cannes experience. "It had been a full day — a morning jog, four interviews (her French is serviceable), a TV short and a rich lunch at the three-star Le Moulin de Mougins—all amid the hustlers and hookers, yachts and yes-men that characterize the international film festival. Now "Merts" (her childhood nickname) was preparing for her big night."

On the opposite page, a photograph of the back of Hemingway's head topped with "a sprig of flowers in her hair" reveals Cannes' vintage cross of glamour and mania — a cascade of tuxedoed photographers wrestling for room on the red carpet and a shot of the young actress. With frenzy of that kind, one can only imagine that Hemingway's smile was akin to Tracy's: shy and appreciative, as if her cheeks and lips were somehow curtsying. Later, as the film's final moments played, Hemingway nearly fainted in the theater. "A doctor was summoned, and Mariel fell into a deep sleep while the others caroused until dawn at the party in her honor downstairs," McMurran writes. "The next morning Mariel blinked awake. 'Did I ruin everything?'"

Her reaction at Cannes matches Tracy's type of distress — one that she too affects with questions rather than statements. At Ike's apartment while she reads reclined on his couch, looking miniature against his wall of books, she responds to his own doubts about their relationship with, "Well don't you have any feelings for me?," "Well don't you want me to stay over?" The following Sunday night at the pizza parlor, upon receiving a letter in the mail accepting her to the Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts in London, she asks Ike, "So what happens to us?" Her featherweight voice (with the inflection of a foreigner) — that in some moments squeaks like "the mouse in the Tom & Jerry cartoon" — appears extra shaky when speaking about matters of the heart. For her, nothing is more perilous than those matters.

Tracy is not yet cynical; she hasn't been corrupted. She hasn't begun referring to friends as "geniuses" and art as "derivative." She insists on "fooling around" instead of fighting in bed. She thumbs her earlobes when she's listening and combs her hair until it's soft. She begins sentences with "Well" and "Guess what?" and asks Isaac "to have a little faith in people."

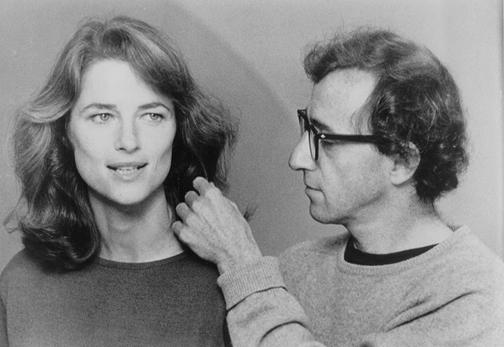

In the film's most devastating scene, the two sit at a soda shop; him with his harmonica and her with her milkshake. Here Hemingway looks especially pure. Her hair is wrapped tight in a french twist, her cardigan is creased on the sleeves (either new or ironed,) and a single ring sits on her pinky finger. Her wide elfin features and thick eyebrows appear holy; the product of one single brushstroke or carved painstakingly out of wax. The moment's melancholy anticipates itself and Isaac breaks up with Tracy. While she dips in and out of adolescence — "Gee, now I don't feel so good" and "I can't believe that you met someone that you like better than me" — her sincerity and logic remain heartbreaking. She lists what they had going for each other and the tally, for any couple, is near perfect.

1. We have laughs together

2. I care about you

3. Your concerns are my concerns

4. We have great sex

While Mariel is no Tracy and Tracy is no Mariel — "I'm different. I'm from Idaho," she told McMurran — their reactions to life are rich and replete with teenage-speak and sage musings. It's no wonder that lines like, "Are you kidding me? You should talk!" came so easily to Hemingway who described her Persian cat to People as "such a nerd" and scoffed at Woody's initial interest in her: "Give me a break." That duality of perceiving oneself and others at a young age while also staying young is incredibly rare and is what freed Manhattan of any precociousness and caprice.

Tracy possesses you like the giant she is, standing five inches taller than Woody, able to cup his head like a basketball or drink it like a coconut with a straw. But her personality compliments and her thoughts are sound: "Maybe we're meant to have a series of relationships at different lengths," or better, "You keep stating [the break up] like it's to my advantage when it's you that wants to get out of it."

In real life too, her words were undisguised: "I feel closer to adulthood now, but it makes me sad. I get excited and depressed. If I have a problem I go to someone or just let it out by screaming and crying. Some people are too young when they become famous. I think I'm old enough to handle it now."

Durga Chew-Bose is the senior editor of This Recording. She is a writer living in Brooklyn. She twitters here and tumbls here. She last wrote in these pages about Teen People magazine.

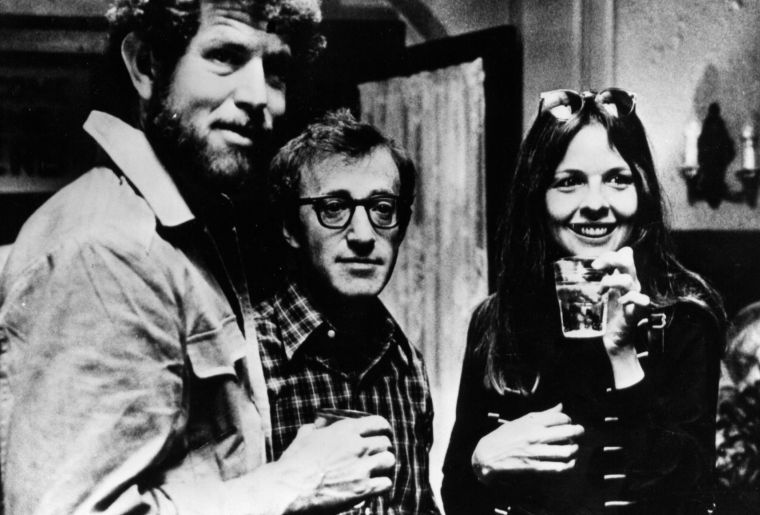

with her sister Margaux

with her sister Margaux

"Red Hunting Jacket" - Little Scream (mp3)

"People Is Place" - Little Scream (mp3)

"The Boatman" - Little Scream (mp3)